By Chang Ching

Two years ago on this day, the Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China issued a statement on establishing the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone. According to “the Statement by the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Establishing the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone,” three PRC domestic laws and administrative rules were addressed as the basis of the East China Sea ADIZ within the following text:

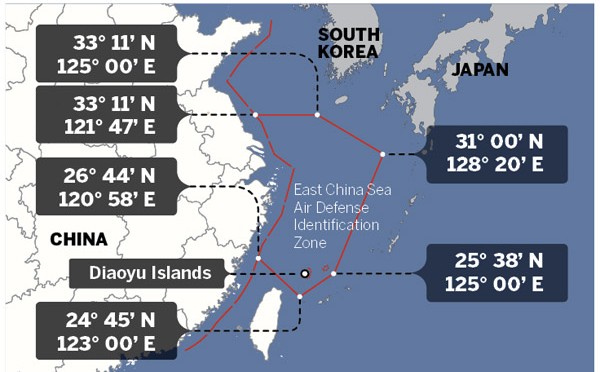

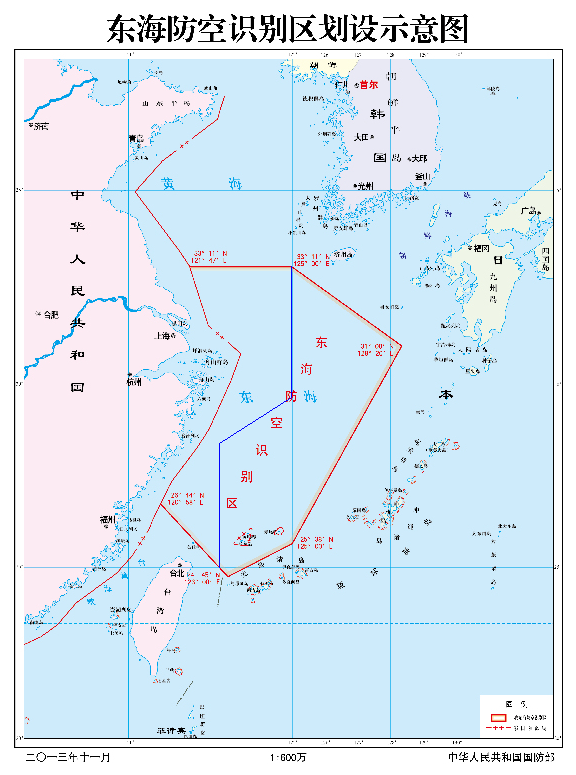

The government of the People’s Republic of China announces the establishment of the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone in accordance with the Law of the People’s Republic of China on National Defense (March 14, 1997), the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Civil Aviation (October 30, 1995) and the Basic Rules on Flight of the People’s Republic of China (July 27, 2001). The zone includes the airspace within the area enclosed by China’s outer limit of the territorial sea and the following six points: 33º11’N (North Latitude) and 121º47’E (East Longitude), 33º11’N and 125º00’E, 31º00’N and 128º20’E, 25º38’N and 125º00’E, 24º45’N and 123º00’E, 26º44’N and 120º58’E.

Further, based on this government statement, China’s Ministry of National Defense issued an announcement of the aircraft identification rules for the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone of the People’s Republic of China as the following text:

The Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China, in accordance with the Statement by the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Establishing the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone, now announces the Aircraft Identification Rules for the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone as follows:

First, aircraft flying in the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone must abide by these rules.

Second, aircraft flying in the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone must provide the following means of identification:

- Flight plan identification. Aircraft flying in the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone should report the flight plans to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China or the Civil Aviation Administration of China.

- Radio identification. Aircraft flying in the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone must maintain the two-way radio communications, and respond in a timely and accurate manner to the identification inquiries from the administrative organ of the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone or the unit authorized by the organ.

- Transponder identification. Aircraft flying in the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone, if equipped with the secondary radar transponder, should keep the transponder working throughout the entire course.

- Logo identification. Aircraft flying in the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone must clearly mark their nationalities and the logo of their registration identification in accordance with related international treaties.

Third, aircraft flying in the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone should follow the instructions of the administrative organ of the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone or the unit authorized by the organ. China’s armed forces will adopt defensive emergency measures to respond to aircraft that do not cooperate in the identification or refuse to follow the instructions.

Fourth, the Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China is the administrative organ of the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone.

Fifth, the Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China is responsible for the explanation of these rules.

Sixth, these rules will come into force at 10 a.m. November 23, 2013.

For the most part, military observers and political commentators have analyzed the matter from the political dimension. What is lacking is an examination of the validity of these three PRC domestic laws and rules as well as their association with the PRC government statement and the subsequent aircraft identification rules.

After reviewing the three laws and rules, i.e. the Law of the People’s Republic of China on National Defense, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Civil Aviation and the Basic Rules on Flight of the People’s Republic of China, noted by the PRC East China Sea ADIZ statement (hereafter, the statement) and the associated aircraft identification rules, we may conclude the following flaws:

First, the effective dates of these three laws and rules noted by the statement are indeed questionable.

For the Law of the People’s Republic of China on National Defense, it was initially put into force on March 14, 1997, as noted by the statement. Likewise, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Civil Aviation was originally put into effect on October 30, 1995, also noted by the statement. Nevertheless, according to the “Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on Amending Some Laws” issued by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on August 27, 2009 and subsequently put into effect by the “Order No.18 of the President of the People’s Republic of China”, the Article 48 of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on National Defense was revised. Similarly, contents or wordings of the Article 191, 192, 193, 194, 195, 196, 197, 198, 199 and 200 of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Civil Aviation were also revised by the same amending process and government document. Hence, the effective dates of these two laws noted by the statement were definitely incorrect after the law amendment process.

Moreover, the Basic Rules on Flight of the People’s Republic of China was not initially put into force as noted by the statement. It was first jointly issued by the PRC State Council and the PRC Central Military Commission on July 24, 2000, by the “Decree No. 288 of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China and the Central Military Commission of the People’s Republic of China” after a large scale revision from its progenitor with the identical title established by the same two institutions on April 21, 1977.

Based on two separate documents but with the same titles known as the “Decision of the State Council and the Central Military Commission on Amending the General Flight Rules of the People’s Republic of China”, it was subsequently twice amended on July 27, 2001 and October 18, 2007. Also, the revised rules were put into force by the “Decree No. 312 of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China and the Central Military Commission of the People’s Republic of China” and “Decree No. 509 of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China and the Central Military Commission of the People’s Republic of China” on August 1, 2001 and November 22, 2007, accordingly. We therefore may notice that the effective date of the Basic Rules on Flight of the People’s Republic of China noted by the statement was neither the initial effective date of the rule nor the latest effective date of the rule.

Based on the survey results already mentioned , we may conclude that the validity and legality of the judiciary documents cited by the statement is undeniably questionable. The quality of this government statement is poor.

Second, the jurisdiction associated with the contents noted by these three laws and rules as compared with the airspace defined by the PRC East China Sea ADIZ can also be problematic. The jurisdiction defined by the Law of the People’s Republic of China on National Defense is basically illusive. It does note with the territorial airspace in its text. Yet, the substantial content of this law has never specifically mentioned its jurisdiction may extend to any air defense identification zone. Likewise, the Article 2 of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Civil Aviation does declare the PRC’s exclusive sovereign rights over its territorial airspace. Many other articles of this law also repeatedly address its jurisdiction over the PRC territorial airspace. By the principle of ratione loci, we may clearly identify the jurisdiction defined by this law never was intended to extend to the airspace over the East China Sea.

On the other hand, according to the Chapter 13 and the Article 173 of the People’s Republic of China on Civil Aviation, its jurisdiction does cover those foreign aircrafts or other flying objects within its territorial airspace. Also, by the terms noted in its Article 182, its jurisdiction may extend to certain search and rescue areas out of its territory. Nonetheless, such search and rescue areas are governed by the international treaties and totally irrelevant with any air defense identification zone.

Basically, the Basic Rules on Flight of the People’s Republic of China is the administrative rule originated from the People’s Republic of China on Civil Aviation. This is exactly the reason why the Article 1 of this rule specifically noted its jurisdiction only covering those aviation activities within the PRC’s territory. However, the Article 2 of the same rule also extends its jurisdiction over those units and persons with the ownership of the aircrafts as well as the personnel relevant to the aviation activities and the activities themselves. There are numerous articles of this rule repeatedly addressing its jurisdiction and objectives involved in the activities within this airspace as well as the aviation activities themselves.

The only exception regarding the jurisdiction out of its territorial airspace ever appeared in this rule is the Article 121 of Chapter XII titled with Supplementary Provisions: “In regard to the aircraft of the People’s Republic of China operating over the contiguous zones, exclusive economic zones or high seas beyond the territorial waters of the People’s Republic of China, where the provisions of an international treaty concluded or acceded to by the People’s Republic of China are different from the provisions of these Rules, the provisions of that international treaty shall apply, except the provisions for which reservation has been declared by the People’s Republic of China.” According to the content noted above, its jurisdiction may only cover the aircraft with the PRC nationality registration. It does not authorize any jurisdiction over foreign aircraft out of its territorial airspace.

After reviewing the content of these three laws and rules, we may very confidently believe that there is no basis of jurisdiction over the East China Sea ADIZ ever granted by them. This is another solid evidence of staff work negligence.

Third, terms or any substantial contents noted by these three laws and rules are never associated with the airspace defined by the statement or the aircraft identification rules requested by the PRC Defense Ministry announcement. The term of the ADIZ itself was never specifically defined by these three legal documents since it never ever appeared in any text of them. Further, for those means of identification demanded by the PRC Defense Ministry announcement, no corresponding regulation has ever been noted in these three laws and rules. Of course, Article 167 and 168 of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Civil Aviation as well as Article 39 and 90 of the Basic Rules on Flight of the People’s Republic of China are noted with the term of flight plan, yet, the substantial content is totally irrelevant with the flight plan identification within the PRC East China Sea ADIZ.

As for the radio identification, the term does appear in the text of the Article 10, 88 and 90 of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Civil Aviation for eight times and in the Article 48, 57, 60, 87, 95, 101 and 105 of the Basic Rules on Flight of the People’s Republic of China for a total of thirteen times. Again, the context of these applications is not relevant to the East China Sea ADIZ identification procedures. The term of secondary radar transponder noted by the transponder identification section of the PRC Defense Ministry announcement of identification rules is never noted in these three legal documents. Last but not least, for the logo identification, the term “logo” itself is mentioned by the Article 8, 58, 61 and 85 of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Civil Aviation five times but the contexts are not substantially associated with the East China Sea ADIZ identification procedures.

Likewise, it was also noted by Article 24, 41 and 47 of the Basic Rules on Flight of the People’s Republic of China for six times. The content of the Article 24 and 47 is totally unrelated to the logo of any aircraft. Only the Article 41, “Aircraft operating within the territory of the People’s Republic of China shall bear distinct identification marks. Aircraft without identification marks are forbidden such flight. Aircraft without identification marks shall, when in need of such flight due to special circumstances, be subject to approval by the Air Force of the People’s Liberation Army. The identification marks of aircraft shall be subject to approval in accordance with the relevant provisions of the State,” the content is seemingly in accordance with the East China Sea ADIZ identification rule. Nonetheless, the jurisdiction of the Article 41 is only within the PRC territory, which is not the airspace defined by the East China Sea ADIZ.

It is noteworthy that there are various airspaces defined by these three laws and rules. Apart from the search and rescue areas mentioned above, the only other airspace that has the coverage out of the PRC territorial airspace is the “Flight Information Region” noted in the Article 30 and the Article 85 to Article 88 of the Basic Rules on Flight of the People’s Republic of China. The significance of the Flight Information Region is clearly defined by the International Civil Aviation Organization. It is totally different from ADIZ declared by any nation in the world. No confusion can happen between these two terms.

The PRC government statements on establishing the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone and the Defense Ministry announcement of the aircraft identification rules within this ADIZ are fundamentally reckless. The PRC East China Sea ADIZ has already existed for almost two years. Can we ask the following questions?

Does the PRC adopt this ADIZ to expand its sovereign claim as many political accusations ever predicted? Does this ADIZ successfully expand the PRC sphere of influence as many commentators ever actively speculated? Does this ADIZ pave the solid foundation for the PLA to exercise its airpower above the East China Sea as many military experts assessed? Do expanding PRC military air activities associate with the mechanism of this ADIZ? How much national pride is substantially acquired after establishing this ADIZ? Whether this ADIZ actually serves the functions as the PRC government originally claimed? And finally, do we fairly and comprehensively judge this issue by excluding our prejudice first?

All readers may have their own answer to these questions. We should never forget that the biased vision may only cause distortion of the fact and creating confusions that hindering us to see the reality. Whether we may fairly observe and assess the regime in Beijing does matter to our future strategic options and welfare.

Chang Ching is a Research Fellow with the Society for Strategic Studies, Republic of China. The views expressed in this article are his own.