The following is a two-part series on China’s possible reactions to the Arbitration Ruling in its dispute with the Philippines. In Part I, the military implications of China’s recent and possible future actions are analyzed. Part II will look at the likely outcome of China using economic and legal leverage to register its displeasure with the ruling.

By Mark E. Rosen

The Arbitration Panel’s ruling against China on July 12 was a stinging blow to China’s international prestige. China advanced a narrative that it had historic rights to nearly the entirety of the South China Sea (SCS), and that it could prevent states like the Philippines and Vietnam from fishing in their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) and drilling for oil near their coasts. China also maintained, through its actions, the right to engage in island building and fishing practices which caused severe damage to the marine environment. Since these activities occurred inside of its Nine Dashed Line Claim (9DL), China felt justified in these “internal matters” and told its neighbors in almost evangelical terms that the SCS is their patrimony and that no country or international body has a right to mess in their domestic affairs. On all these counts, the Tribunal disagreed and issued a strong rebuke of China’s activities.

The few positive signs that China is receptive to peaceful resolution and has moved past the ruling have been overtaken by a number of very disturbing trends which, regardless of which path China ultimately takes, puts it on a collision course with Japan, the United States, or even a much broader group of states. Unless something dramatic emerges as a result of the secret conclave in Beidaihe, the negative developments seem to overwhelmingly demonstrate that China’s gaze is only focused on settling scores with the U.S., Japan, Vietnam and the Philippines, because these states are responsible for its legal embarrassment and loss of face within ASEAN.

China’s Negative Reactions to the Ruling

Immediately after the ruling, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a detailed repudiation of the ruling on July 12; declaring that the ruling was “null and void,” “has no binding force,” and that “China neither accepts nor recognizes it.” It also stated that the Philippine’s actions in filing the action were “unilateral” and a “violation of international law,” because the Philippines deviated from its legal commitment in the 2002 ASEAN Declaration of Conduct (DOC) to resolve differences via negotiations. China, in the same breath, reaffirmed its commitment to international law and to peace and stability in the South China Sea. Two days later, the Chinese state media declared the permanent court of arbitration a “puppet” of external forces and that “China will take all necessary measures to protect its territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests.” Since then, the following developments have taken place:

- On July 13, China sent civilian aircraft to two new airports on Mischief Reef and Subi Reef. This action was taken in spite of the Tribunal’s ruling that Mischief Reef is a low-tide elevation and part of the Philippine continental shelf, and Subi Reef is a low tide elevation and part of the territorial sea of Itu Aba. In both cases, low-tide elevations cannot be appropriated by China.

- On July 13, China’s vice foreign minister asserted, “If our security is being threatened, of course we have the right to demarcate a [air defense identification] zone.”

- On July 15, China posted images of its recent overflight of the highly contested Scarborough Shoal by nuclear capable H-6K bombers (and escorts) and announced that such patrols would be a “Regular Practice.” This announcement came the same day as the U.S. Navy’s Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Adm. John Richardson was visiting his Chinese counterpart, Adm. Wu Shengli.

- On July 18, Press reports cited Adm. Wu Shengli as warning the U.S. CNO that future U.S. freedom of navigation operations “will only backfire” and that Beijing will complete its planned land reclamation and reef reclamation and has made “sufficient preparations” to deal with any sovereignty infringements.

- On July 19, China’s vice minister of commerce Gao Yan told reporters that trade relations between China and the Philippines were “mutually beneficial,” and added that the government did not endorse calls within China to boycott Philippine products. There were also reports of Chinese activities smashing iPhones and massing protests in front of KFC restaurants in several cities.

- On July 24, ASEAN failed to achieve consensus to issue a statement on the Tribunal decision after China’s ally, Cambodia, broke away from a consensus document that was being proposed by the Philippines, Vietnam, and others.

- On July 25, the United States, Australia, and Japan held a Trilateral Strategic Dialogue and issued a statement expressing “their strong support for the rule of law and called on China and the Philippines to abide by the Arbitral Tribunal’s Award of July 12 in the Philippines-China arbitration, which is final and legally binding on both parties.” The ministers also expressed opposition to any coercive or unilateral actions that could alter the status quo including future land reclamation activities.

- On July 27, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi dismissed the Trilateral statement and charged that the statement was not constructive and was “fanning the flames.” Foreign Ministry spokesman Lu Kang also charged that the U.S., Australia, and Japan have been adopting double standards towards international law which they adopt when it “fits their needs.”

- On July 28, The Chinese Defense Ministry announced plans to hold a joint military exercise with Russia in the SCS in September; the first such bilateral exercise in that body of water.

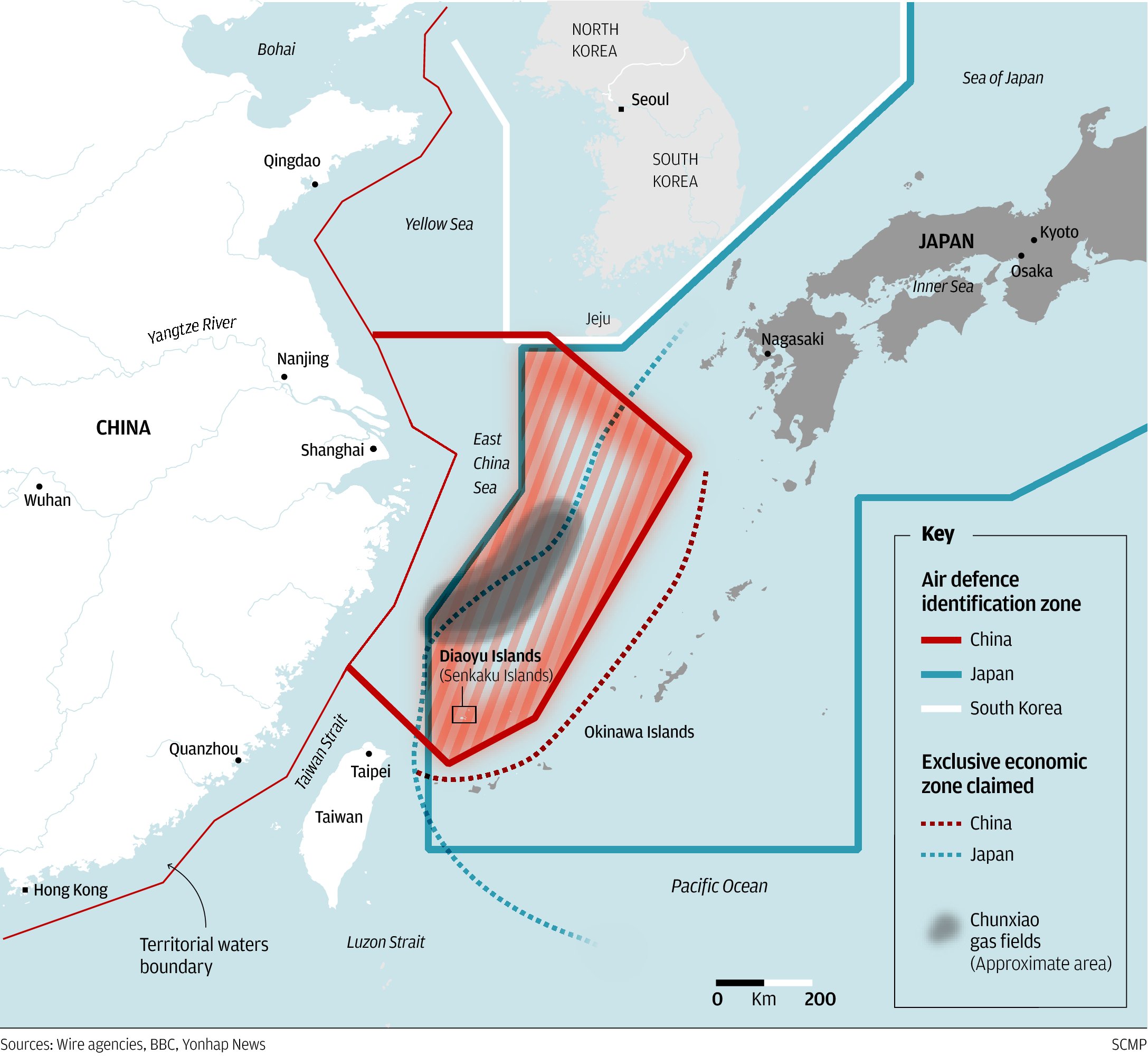

- On August 1, China held a significant live fire drill in the East China Sea (ECS) that included the firing of “dozens” of missiles and torpedoes. (AP, Aug 2, 2016). There were also reports that six PRC coast guard vessels and over 200 fishing vessels swarmed in the vicinity of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands.

- On August 2, Japan’s Ministry of Defense published a white paper describing China’s position on the SCS an object of “deep concern.” China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs called Japan’s paper “full of malice,” “lousy clichés,” and “irresponsible” and a smokescreen to obscure Japan’s expansionist arms policies. This exchange of statements was then followed by North Korea’s firing of a ballistic missile into Japan’s EEZ on August 3. When the UN Security Council sought to condemn North Korea’s actions, China “curtailed” the Security Council’s actions.

- On August 2, China’s Supreme People’s Court clarified China’s 2014 Fishing Regulation to the effect that those that engage in illegal activities inside of the waters claimed by China will be arrested and tried as criminals. This decision settled past differences of opinion as to whether China’s EEZ and Territorial Seas empowered Chinese officials to pursue criminal liability for those involved in illegal hunting or fishing in China’s jurisdictional seas. The practical import is that fishing within the 9DL area will be met with vessel seizure and imprisonment.

- On August 2, Malaysia joined Indonesia in announcing that they would sink any foreign ships that are fishing in their claimed waters. This statement was a veiled threat to China that had allowed its “fishing militia” to fish in waters claimed by both countries.

- On August 6, China sent bombers and fighter jets on patrol in the vicinity of “Scarborough Shoals.” China announced that these flights would be a “regular practice” to “normalize South China Sea combat patrols” to safeguard its sovereignty interests.

Converging Flash Points

Much like current U.S. presidential campaign antics, it is hard to imagine what is likely to happen next in the high stakes poker game being played out in Asian waters. Taking into account what has happened to date and where China believes that it has leverage, there are three possible ways in which China might lash out: military, economic, and legal.

Possible Military Moves by China: The Senkakus

The statements by China’s Chief of the Naval Staff and its military activity near the Senkakus suggest that China is employing tactics of intimidation to get Japan to back away from its recent statements over the Tribunal’s decision. It may also be the case that the presence of swarming vessels in and around the Senkakus and the North Korean missile shot (presumably with tacit PRC approval) suggest that China is trying to goad Japan to militarily respond or back off its claims.

The Senkakus have always been the powder keg of Asia because it features the two leading powers in Asia: one ascending and one arguably in decline both competing on the world stage. Both are rivals for dominance over a tiny scrap of land and associated maritime space which, given the implications for access to fisheries and oil and gas, is not irrational. This is somewhat ironic because the Tribunal decision in China v. the Philippines takes away much of the incentive for the two states to fight over these rocks since they would be enclaved within the continental shelf of one of the two states; most likely Japan. In that case, the rocks themselves and the surrounding territorial sea have much less value that the large continental shelf projections of each country and aren’t worth fighting over. (See, Fixing the Senkaku/Diaoyu Problem Once and For All ).

It is somewhat curious that China is lashing out at Japan, given that the Senkaku/Diaoyu issue has been rather quiet until recently and the SCS is China’s current problem. Regardless, China would do well to revisit its strategic objectives, especially since the United States declared in April of 2014 that Japan is the lawful administrator of the islands and are within the scope of Article 5 of the 1961 Mutual Defense Treaty. The reaffirmation of solidarity between U.S., Australia, and Japan in the July 25 Trilateral declaration likely provides Tokyo the fortitude it needs to militarily respond if China continues to operate provocatively near the Senkakus.

Another important point in this calculus is Japanese President Shinzo Abe. Abe stated in 2015 that Japan is a “maritime state” and can “only ensure its own peace and security by actively engaging in efforts to make the entire world a more peaceful and secure place.” Japan’s record 2016 military budget of roughly $42 billion is further evidence of that goal. Japan has a combatant fleet of 131 vessels, including 3 aircraft carriers, 43 destroyers, and 17 submarines using frontline U.S. tactics and systems. China has substantially more hulls and submarines, but most naval analysts interviewed by the author cite the excellent Japanese submarine force as a likely game changer.

More important is the will to fight. Japan, as noted, has been greatly increasing its military spending even though its economy has been in the doldrums. According to the OECD, output growth has been slowed by a drop in demand from China and other Asian countries and by sluggish private consumption. This indicates that if Japan is pushed to the point that it must militarily respond, it has three valid reasons for using instant and overwhelming force now. First, Japan’s economy is too fragile to become involved in a protracted war with China. It would need to win fast and win big to reestablish economic dominance within Asia. If China is not dealt a mortal blow and forced to capitulate, it will use its economic leverage to coerce states to suspend trading with Japan. Japan’s trading economy cannot easily weather a suspension of its trade relations – even if the U.S. and Australia remain in their corner. Second, Japan cannot win a military war of attrition with China: it suffers from a lack of hulls, aircraft, personnel, and production capacity.

Like Israel did in the 1967 six-day attack on Egypt, Jordan, and Syria, Japan would feel compelled to use its current qualitative advantages to deliver a massive blow to Chinese maritime and air forces to dissuade Beijing from further military incursions in the ECS. In a few years, the military edge could shift to China because of its massive building plans. Third, Japanese domestic politics today would likely support a massive strike. This starts with Japan’s new self-defense law which entered into force in March of 2016 and allows Japan to engage in limited coalition warfare. Also, a 2012 Public Opinion Poll by the Cabinet Office shows a nose-dive in Japanese attitudes towards China. According to a 2013 paper by Stimson Center Analyst Yuki Tatsumi Chinese economic ascendancy has been a source of friction as has been the influx of Chinese citizens into Japan as members of the workforce or as tourists. People complain of the increases in crime by Chinese living and working in Japan and bad manners. Finally, the Japanese public is extremely well read and are likely becoming unnerved and physically threatened by the constant scrambling of Japanese fighters (200 times alone in April – June) to intercept Chinese aircraft, ballistic missile tests by China’s “Puppet” in Pyongyang, and live fire exercises in the Senkakus.

China needs to ask itself what it is trying to achieve in the ECS. If its intent is to beat Tokyo into submission or lure it into a limited and protracted war of attrition to undermine public support for Abe, it seems very unlikely that Tokyo will take the bait. However, if its intent is to successfully provoke a full-scale military attack, they are likely to be very disappointed, particularly since U.S. forces will be present to backstop the protection of Japan’s homeland. They may also be gravely miscalculating that Japan will only respond to Beijing’s move in a piecemeal fashion. Japan has an excellent and professional Navy – especially its submarine force – and could deliver a knock-out punch to much of China’s maritime forces.

Possible Military Moves by China: An Actual or De Facto South China Sea ADIZ

Until the combat patrols on August 6 near Scarborough Shoal, Beijing’s recent attention seemed focused on the East China Sea. However, while Chinese threats to establish an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the SCS seemed to have died down, the possibility cannot be reasonably excluded. The question then becomes: does an ADIZ advance China’s campaign to assert its sovereignty in the South China Sea? If China concludes that an ADIZ will send the correct signal that it has sovereignty claims in the SCS, the next concerns are the likely responses and whether or not they can succeed.

The United States was the first country to establish an ADIZ during the height of the Cold War as a way of providing notice to Soviet flights entering the zone near the United States that the United States reserved the right to undertake a radio challenge or dispatch fighter aircraft to ascertain the incoming flights course and intentions if it was not flying on a predetermined flight plan. The United States now has four ADIZs in operation: the U.S. ADIZ (Continental U.S.); Alaska ADIZ, Guam ADIZ, and Hawaii ADIZ. Upwards of 20 other countries have established these zones adjacent to their coastlines. These zones do not seek to restrict freedoms of navigation or overflight; their sole purpose is to ascertain a particular flights intention to reassure the coastal state that no surprise attack is being launched. When China established its ADIZ in late 2013 over the contested Senkaku islands, it was diplomatically protested because it was overbroad and inappropriate to defend an uninhabited rock as a sort of occupation measure. China’s ECS ADIZ was also criticized for including civil aircraft flying on established flight plans.

ADIZs have no explicit foundation in UNCLOS or other international instruments, yet they are regarded as customary and lawful when used for the limited purpose of identifying aircraft near a country’s coastline, not to deny such aircraft their lawful rights of overflight. For this reason, the United States and other countries protested the Chinese ADIZ, since it was established to “control and react to aircraft entering the zone” and warned that aircraft flying in the ECS Zone “must comply” with the requirements to provide detailed identification data and “comply with the instructions” of the zone controller.

The same legal issues in China’s ECS zone would apply in a SCS Zone. Depending on how it was actually constituted, it would certainly be provocative because it is not associated mainland protection but rather protection of mostly uninhabited rocks and islets from surprise attack. As it relates to military aircraft lawfully operating in the SCS, there is a fear that China will seek to limit military flights to corridors that they can instrument and hold at risk with missiles. There are also the impacts of a large SCS ADIZ and the impact on civil aviation. According to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the South China Sea is a “Main Truck” for all traffic on “all routes” and there are concerns that added reporting and routing by Chinese civil authorities will impede international air traffic.

The last possibility is that China, through deeds and action, will establish a de facto ADIZ as an adjunct of its promised combat air patrols. It might simply declare that all aircraft flying in the SCS have to provide flight information to Chinese Military authorities or risk interception or being shot down.

In the last analysis, if China were to establish an actual or de facto ADIZ encompassing the SCS and used the same sort of rules as its ECS ADIZ, the United States will almost certainly protest the action and fly combat aircraft into those portions of the ADIZ which are illegitimate. Australia and France are two other states that are also unlikely to stand idly by if a SCS ADIZ is established because of Australia’s longstanding commitment to UNCLOS, order at sea, and also because of the verbal barrage which it received from China following the Trilateral Strategic Dialogue statement. Also, this support from Australia is consistent with the U.S./Australia Security Treaty of 1952 in which security guarantees are triggered by an “armed attack in the Pacific Area on any of the Parties.” Finally, France announced at the Shangri-La Dialogue Forum in June that it would, on its own right, conduct “regular and visible” patrols in the South China Sea. This is logical, because France frequently operates in those waters in conjunction with the protection of its vast South Pacific Territories. The French defense minister has also urged the EU to also join in these patrols to reinforce “a rules-based maritime order.” Great Britain, Vietnam, and India are other countries voicing public support for the ruling and could conceivably contribute to a “FON Coalition.”

If China goes forward with an ADIZ, it is very reasonable to expect that the United States, France, Australia and even Japan will mount FON-like operations to protest with the zone’s establishment. If these operations are “regular and visible” as suggested by France, China would need to ask itself whether or not it is is achieving its political objectives when foreign aircraft can operate with impunity in their new ADIZ. Also, if China continues to engage in persistent combat patrols around Scarborough Shoal, then a declaration that the United States that regards Scarborough to be within the scope of the “metropolitan territory” of the Philippines under Article V of the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty is both possible and a fresh challenge to Beijing that would cause it embarrassment.

China puts itself greatly at risk if it moves forward with an ADIZ or something resembling it given the widespread international support for the Tribunal Ruling, abhorrence with China’s behavior towards its neighbors, and general concern that China’s bad behavior be deterred. Now that the U.S. has bed down rights in five bases in the Philippines adjacent to the South China Sea, it has gained a significant military advantage in being able to operate fixed wing combat aircraft from land locations to conduct its own FON operations or combat patrols that don’t put a carrier at risk. China’s ADIZ gamble might have paid off if only the United States were involved so that it could “declare victory” in a future contacts with U.S. ships or aircraft such as the EP3 incident. However, given the threat dynamic and the potential to trigger alliance support from Australia and France, China will hopefully conclude that it will be biting off more than it can chew by going down the ADIZ path or, as noted above, further provoking Japan in the East China Sea.

A maritime and international lawyer, Mark E. Rosen is the SVP and General Counsel of CNA and holds an adjunct faculty appointment at George Washington School of Law. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author alone and do not represent the views of CNA or any of its sponsors.

Featured Image:Japanese submarine Oyashio arrives at the former U.S. naval base in Subic bay. (AFP)