By Christopher Nelson

At the end of our discussion about the Eighteenth-Century British Royal Navy and her new book, Disciplining the Empire, I asked Professor Kinkel what books she would teach in a graduate level course on maritime history. She kindly provided me a draft syllabus of the books that she would have her students read.

There are some fascinating titles to add to your reading list. A short description from the publisher follows each book.

From the Atlantic to the Mediterranean (and Beyond)

Carlo M. Cipolla, Guns, Sails and Empires: Technological Innovation and the Early Phases of European Expansion, 1400-1700 (New York: Sunflower Univ. Press, 1966)

“Guns, Sails and Empires is that rarity among works of history: a short book with a simple, powerful thesis that the entire book is devoted to proving. Carlo Cipolla begins with the question, “Why, after the end of the fifteenth century were the Europeans able not only to force their way through to the distant Spice Islands but also to gain control of all the major sea-routes and to establish overseas empires.” (Amazon)

Richard T. Rapp, “The Unmaking of the Mediterranean Trade Hegemony: International Trade Rivalry and the Commercial Revolution,” Journal of Economic History, 35.3 (1975): 499–525

“The shift in the locus of European trade from the markets of the Mediterranean to the North Atlantic overthrew a centuries old pattern of commerce and established the basis for the predominant role of North Atlantic Europe in the era of industrialization. While the expression “commercial revolution” no longer has quite the currency that it once enjoyed, students of the early modern economy have not been negligent about trying to understand the causes of the commercial shift. The impact of entrepreneurship and Weltanschauung, capital accumulation, technical innovation in shipping and industry, and the economic and political organization of nation-states have all received attention from students of the age.” (Cambridge/Journal of Economic History)

Herman Van Der Wee, “Structural Changes in European Long-Distance Trade, and Particularly in the Re-Export Trade from South to North, 1350–1750,” in The Rise of Merchant Empires: Long-distance Trade in the Early Modern World, 1350–1750, ed. James D. Tracy (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1990), pp. 14–33

“European dominance of the shipping lanes in the early modern period was a prelude to the great age of European imperial power in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Yet in the present age we can see that the pre-imperial age was in fact more an ‘age of partnership’ or an ‘age of competition’ when the West and Asia vied on even terms. The essays in this volume examine, on a global basis, the many different trading empires from the end of the Middle Ages to the eighteenth century.” (Amazon)

Commodities and Trade

Molly Warsh, American Baroque: Pearls and the Nature of Empire, 1492–1700 (Omohundro Institute, 2018)

“Pearls have enthralled global consumers since antiquity, and the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella explicitly charged Columbus with finding pearls, as well as gold and silver, when he sailed westward in 1492. American Baroque charts Spain’s exploitation of Caribbean pearl fisheries to trace the genesis of its maritime empire. In the 1500s, licit and illicit trade in the jewel gave rise to global networks, connecting the Caribbean to the Indian Ocean to the pearl-producing regions of the Chesapeake and northern Europe.

Pearls—a unique source of wealth because of their renewable, fungible, and portable nature—defied easy categorization. Their value was highly subjective and determined more by the individuals, free and enslaved, who produced, carried, traded, wore, and painted them than by imperial decrees and tax-related assessments. The irregular baroque pearl, often transformed by the imagination of a skilled artisan into a fantastical jewel, embodied this subjective appeal. Warsh blends environmental, social, and cultural history to construct microhistories of peoples’ wide-ranging engagement with this deceptively simple jewel. Pearls facilitated imperial fantasy and personal ambition, adorned the wardrobes of monarchs and financed their wars, and played a crucial part in the survival strategies of diverse people of humble means. These stories, taken together, uncover early modern conceptions of wealth, from the hardscrabble shores of Caribbean islands to the lavish rooms of Mediterranean palaces.” (Amazon)

Nuala Zahedieh, The Capital and the Colonies: London and the Atlantic Economy, 1660–1700 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010)

“Between 1660 and 1700, London established itself as the capital and commercial hub of a thriving Atlantic empire, accounting for three quarters of the nation’s colonial trade, and playing a vital coordinating role in an increasingly coherent Atlantic system. Nuala Zahedieh’s unique study provides the first detailed picture of how that mercantile system was made to work. By identifying the leading colonial merchants, she shows through their collective experiences how London developed the capabilities to compete with its continental rivals and ensure compliance with the Navigation Acts. Zahedieh shows that in making mercantilism work, Londoners helped to create the conditions which underpinned the long period of structural change and economic growth which culminated in the Industrial Revolution.” (Amazon)

Patrick O’Brien, “European Economic Development: The Contribution of the Periphery,”Economic History Review, 35.1 (1982): 1–18

“Economic history has enjoyed a revival in the study of development. Provocative interpretations of the course and causes of long-term growth continue to emerge from the writings of Immanuel Wallerstein, Gunder Frank and Samir Amin. While the basic purpose of their research is to explore the origins of underdevelopment, their commitment to a ‘global perspective’ has led them into wide ranging excursions into the economic history of Western Europe because, to quote Wallerstein, ‘Neither the development nor underdevelopment of any specific territorial unit can be analyzed or interpreted without fitting it into the cyclical rhythms and secular trends of the world economy as a whole.'”

People at Sea

Kris Lane, Pillaging the Empire: Global Piracy on the High Seas, 1500–1750, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2016)

“Between 1500 and 1750, European expansion and global interaction produced vast wealth. As goods traveled by ship along new global trade routes, piracy also flourished on the world’s seas. Pillaging the Empire tells the fascinating story of maritime predation in this period, including the perspectives of both pirates and their victims. Brushing aside the romantic legends of piracy, Kris Lane pays careful attention to the varied circumstances and motives that led to the rise of this bloodthirsty pursuit of riches, and places the history of piracy in the context of early modern empire building.

This second edition of Pillaging the Empire has been revised and expanded to incorporate the latest scholarship on piracy, maritime law, and early modern state formation. With a new chapter on piracy in East and Southeast Asia, Lane considers piracy as a global phenomenon. Filled with colorful details and stories of individual pirates from Francis Drake to the women pirates Ann Bonny and Mary Read, this engaging narrative will be of interest to all those studying the history of Latin America, the Atlantic world, and the global empires of the early modern era.” (Amazon)

Marcus Rediker, Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: Merchant Seamen, Pirates and the Anglo-American Maritime World, 1700–1750, 2nd ed. (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1989)

“The common seaman and the pirate in the age of sail are romantic historical figures who occupy a special place in the popular culture of the modern age. And yet in many ways, these daring men remain little known to us. Like most other poor working people of the past, they left few first-hand accounts of their lives. But their lives are not beyond recovery. In this book, Marcus Rediker uses a huge array of historical sources (court records, diaries, travel accounts, and many others) to reconstruct the social cultural world of the Anglo-American seamen and pirates who sailed the seas in the first half of the eighteenth century. Rediker tours the sailor’s North Atlantic, following seamen and their ships along the pulsing routes of trade and into rowdy port towns. He recreates life along the waterfront, where seafaring men from around the world crowded into the sailortown and its brothels, alehouses, street brawls, and city jail.

His study explores the natural terror that inevitably shaped the existence of those who plied the forbidding oceans of the globe in small, brittle wooden vessels. It also treats the man-made terror–the harsh discipline, brutal floggings, and grisly hangings–that was a central fact of life at sea. Rediker surveys the commonplaces of the maritime world: the monotonous rounds of daily labor, the negotiations of wage contracts, and the bawdy singing, dancing, and tale telling that were a part of every voyage. He also analyzes the dramatic moments of the sailor’s existence, as Jack Tar battled wind and water during a slashing storm, as he stood by his “brother tars” in a mutiny or a strike, and as he risked his neck by joining a band of outlaws beneath the Jolly Roger, the notorious pirate flag. Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea focuses upon the seaman’s experience in order to illuminate larger historical issues such as the rise of capitalism, the genesis the free wage labor, and the growth of an international working class. These epic themes were intimately bound up with everyday hopes and fears of the common seamen.” (Amazon)

Sowande M. Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea: Terror, Sex, and Sickness in the Middle Passage (Univ. of Illinois Press, 2016)

“Most times left solely within the confine of plantation narratives, slavery was far from a land-based phenomenon. This book reveals for the first time how it took critical shape at sea. Expanding the gaze even more widely, the book centers on how the oceanic transport of human cargoes–known as the infamous Middle Passage–comprised a violently regulated process foundational to the institution of bondage. Sowande’ Mustakeem’s groundbreaking study goes inside the Atlantic slave trade to explore the social conditions and human costs embedded in the world of maritime slavery. Mining ship logs, records and personal documents, Mustakeem teases out the social histories produced between those on traveling ships: slaves, captains, sailors, and surgeons. As she shows, crewmen manufactured captives through enforced dependency, relentless cycles of physical, psychological terror, and pain that led to the making–and unmaking–of enslaved Africans held and transported onboard slave ships. Mustakeem relates how this process, and related power struggles, played out not just for adult men, but also for women, children, teens, infants, nursing mothers, the elderly, diseased, ailing, and dying. As she does so, she offers provocative new insights into how gender, health, age, illness, and medical treatment intersected with trauma and violence transformed human beings into the most commercially sought commodity for over four centuries.”

Dean King and John B. Hattendorf, eds. Every Man Will Do His Duty: An Anthology of Firsthand Accounts from the Age of Nelson (Henry Holt, 1997)

“The history of the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars comes alive through letters, diaries, official chronicles, accounts of life at sea, and eyewitness descriptions of great sea battles, such as Cape St. Vincent and Trafalgar, the death of Nelson, and more.” (Amazon)

A Maritime World

Andrew Lipman, The Saltwater Frontier: Indians and the Contest for the American Coast (Yale Univ. Press, 2015)

“Andrew Lipman’s eye-opening first book is the previously untold story of how the ocean became a “frontier” between colonists and Indians. When the English and Dutch empires both tried to claim the same patch of coast between the Hudson River and Cape Cod, the sea itself became the arena of contact and conflict. During the violent European invasions, the region’s Algonquian-speaking Natives were navigators, boatbuilders, fishermen, pirates, and merchants who became active players in the emergence of the Atlantic World. Drawing from a wide range of English, Dutch, and archeological sources, Lipman uncovers a new geography of Native America that incorporates seawater as well as soil. Looking past Europeans’ arbitrary land boundaries, he reveals unseen links between local episodes and global events on distant shores.” (Amazon)

Michael Jarvis, In the Eye of All Trade: Bermuda, Bermudians, and the Maritime Atlantic World,1680–1783 (Chapel Hill: Omohundro Institute, 2012)

“In an exploration of the oceanic connections of the Atlantic world, Michael J. Jarvis recovers a mariner’s view of early America as seen through the eyes of Bermuda’s seafarers. The first social history of eighteenth-century Bermuda, this book profiles how one especially intensive maritime community capitalized on its position “in the eye of all trade.”

Jarvis takes readers aboard small Bermudian sloops and follows white and enslaved sailors as they shuttled cargoes between ports, raked salt, harvested timber, salvaged shipwrecks, hunted whales, captured prizes, and smuggled contraband in an expansive maritime sphere spanning Great Britain’s North American and Caribbean colonies. In doing so, he shows how humble sailors and seafaring slaves operating small family-owned vessels were significant but underappreciated agents of Atlantic integration.

The American Revolution starkly revealed the extent of British America’s integration before 1775 as it shattered interregional links that Bermudians had helped to forge. Reliant on North America for food and customers, Bermudians faced disaster at the conflict’s start. A bold act of treason enabled islanders to continue trade with their rebellious neighbors and helped them to survive and even prosper in an Atlantic world at war. Ultimately, however, the creation of the United States ended Bermuda’s economic independence and doomed the island’s maritime economy.” (Amazon)

Benjamin Carp, “Port in a Storm: The Boston Waterfront as Contested Space, 1747–74,” Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution (Oxford Univ. Press, 2009), pp. 23–61

“The cities of eighteenth-century America packed together tens of thousands of colonists, who met each other in back rooms and plotted political tactics, debated the issues of the day in taverns, and mingled together on the wharves or in the streets. In this fascinating work, historian Benjamin L. Carp shows how these various urban meeting places provided the tinder and spark for the American Revolution.

Carp focuses closely on political activity in colonial America’s five most populous cities–in particular, he examines Boston’s waterfront community, New York tavern-goers, Newport congregations, Charleston’s elite patriarchy, and the common people who gathered outside Philadelphia’s State House. He shows how–because of their tight concentrations of people and diverse mixture of inhabitants–the largest cities offered fertile ground for political consciousness, political persuasion, and political action. The book traces how everyday interactions in taverns, wharves, and elsewhere slowly developed into more serious political activity. Ultimately, the residents of cities became the first to voice their discontent. Merchants began meeting to discuss the repercussions of new laws, printers fired up provocative pamphlets, and protesters took to the streets. Indeed, the cities became the flashpoints for legislative protests, committee meetings, massive outdoor gatherings, newspaper harangues, boycotts, customs evasion, violence and riots–all of which laid the groundwork for war.

Ranging from 1740 to 1780, this groundbreaking work contributes significantly to our understanding of the American Revolution. By focusing on some of the most pivotal events of the eighteenth century as they unfolded in the most dynamic places in America, this book illuminates how city dwellers joined in various forms of political activity that helped make the Revolution possible.” (Amazon)

Bringing the Sea Home

Nicholas Rogers, Mayhem: Post-War Crime and Violence in Britain, 1748–1753 (Yale Univ. Press, 2012)

“After the end of the War of Austrian Succession in 1748, thousands of unemployed and sometimes unemployable soldiers and seamen found themselves on the streets of London ready to roister the town and steal when necessary. In this fascinating book Nicholas Rogers explores the moral panic associated with this rapid demobilization.

Through interlocking stories of duels, highway robberies, smuggling, riots, binge drinking, and even two earthquakes, Rogers captures the anxieties of a half-decade and assesses the social reforms contemporaries framed and imagined to deal with the crisis. He argues that in addressing these events, contemporaries not only endorsed the traditional sanction of public executions, but wrestled with the problem of expanding the parameters of government to include practices and institutions we now regard as commonplace: censuses, the regularization of marriage through uniform methods of registration, penitentiaries and police forces.”

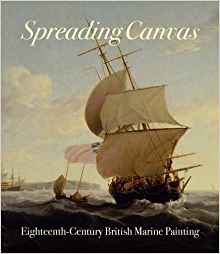

Eleanor Hughes, ed., Spreading Canvas: Eighteenth-Century British Marine Painting (Yale Univ. Press, 2016)

Spreading Canvas takes a close look at the tradition of marine painting that flourished in 18th-century Britain. Drawing primarily on the extensive collections of the Yale Center for British Art and the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London, this publication shows how the genre corresponded with Britain’s growing imperial power and celebrated its increasing military presence on the seas, representing the subject matter in a way that was both documentary and sublime. Works by leading purveyors of the style, including Peter Monamy, Samuel Scott, Dominic Serres, and Nicholas Pocock, are featured alongside sketches, letters, and other ephemera that help frame the political and geographic significance of these inspiring views, while also establishing the painters’ relationships to concurrent metropolitan art cultures. This survey, featuring a wealth of beautifully reproduced images, demonstrates marine painting’s overarching relevance to British culture of the era.

Spreading Canvas takes a close look at the tradition of marine painting that flourished in 18th-century Britain. Drawing primarily on the extensive collections of the Yale Center for British Art and the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London, this publication shows how the genre corresponded with Britain’s growing imperial power and celebrated its increasing military presence on the seas, representing the subject matter in a way that was both documentary and sublime. Works by leading purveyors of the style, including Peter Monamy, Samuel Scott, Dominic Serres, and Nicholas Pocock, are featured alongside sketches, letters, and other ephemera that help frame the political and geographic significance of these inspiring views, while also establishing the painters’ relationships to concurrent metropolitan art cultures. This survey, featuring a wealth of beautifully reproduced images, demonstrates marine painting’s overarching relevance to British culture of the era.

Geoff Quilley, “Art History and Double Consciousness: Visual Culture and Eighteenth-Century Maritime Britain,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 48:1 (2014): 21–35

“This article addresses eighteenth-century maritime visual culture and its historiography by questioning fundamental fractures within it and the implications of these for the disciplines of history and art history. Using the Abolitionist print of the Brooks slave ship as a starting point alongside Paul Gilroy’s formulation of “double consciousness,” it questions the bypassing of the Black Atlantic and the wider maritime sphere within the history of eighteenth-century British art and argues for a revision of the periodization, classification, disciplinary boundaries, and ideological parameters by which it has been defined, to take full account of the significance of the maritime sphere.” (Project Muse)

Projecting Power

Richard Harding, Seapower and Naval Warfare, 1650–1830 (Routledge, 1999)

“From the author of ‘Amphibious Warfare in the Eighteenth Century’ and ‘The Evolution of the Sailing Navy, 1509-1815”, this book serves as a single- volume survey of war at sea and the expansion of naval power in the 18th century. The book is intended for undergraduate courses on 18th century European history, and for amateur and professional military historians, and for navy colleges, and navy and ex-navy professionals.”

Sam Willis, Fighting at Sea in the Eighteenth Century: The Art of Sailing Warfare (Boydell Press, 2008)

Our understanding of warfare at sea in the eighteenth century has always been divorced from the practical realities of fighting at sea under sail; our knowledge of tactics is largely based upon the ideas of contemporary theorists [rather than practitioners] who knew little of the realities of sailing warfare, and our knowledge of command is similarly flawed. In this book the author presents new evidence from contemporary sources that overturns many old assumptions and introduces a host of new ideas. In a series of thematic chapters, following the rough chronology of a sea fight from initial contact to damage repair, the author offers a dramatic interpretation of fighting at sea in the eighteenth century, and explains in greater depth than ever before how and why sea battles (including Trafalgar) were won and lost in the great Age of Sail. He explains in detail how two ships or fleets identified each other to be enemies; how and why they maneuvered for battle; how a commander communicated his ideas, and how and why his subordinates acted in the way that they did. (Amazon)

N.A.M. Rodger, The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy (W.W. Norton, 1986)

“Meticulously researched, Rodger’s portrait draws the reader into this fascinatingly complex world with vivid, entertaining characters and full details of life below the decks. The Wooden World provides the most complete history of a navy at any age, and is sure to be an indispensable volume for all fans of Patrick O’Brian, English history, and naval history.”

Sam Willis, The Struggle for Sea Power: A Naval History of the American Revolution (W.W.Norton, 2016)

“The American Revolution involved a naval war of immense scope and variety, including no fewer than twenty-two navies fighting on five oceans―to say nothing of rivers and lakes. In no other war were so many large-scale fleet battles fought, one of which was the most strategically significant naval battle in all of British, French, and American history. Simultaneous naval campaigns were fought in the English Channel, the North and Mid-Atlantic, the Mediterranean, off South Africa, in the Indian Ocean, the Caribbean, the Pacific, the North Sea and, of course, off the eastern seaboard of America. Not until the Second World War would any nation actively fight in so many different theaters.

In The Struggle for Sea Power, Sam Willis traces every key military event in the path to American independence from a naval perspective, and he also brings this important viewpoint to bear on economic, political, and social developments that were fundamental to the success of the Revolution. In doing so Willis offers valuable new insights into American, British, French, Spanish, Dutch, and Russian history.

This unique account of the American Revolution gives us a new understanding of the influence of sea power upon history, of the American path to independence, and of the rise and fall of the British Empire.” (Amazon)

Sarah Kinkel received her PhD from Yale University in 2012. From 2012-2015, she was the managing editor of Eighteenth-Century Studies. She has since taught as an Assistant Professor at Ohio University.

Christopher Nelson is a U.S. Naval Officer stationed at the U.S. Pacific Fleet Headquarters. He is a graduate of the U.S. Naval War College and the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School. He is a regular contributor to CIMSEC. The questions and views here are his own.

Featured Image: (Pixabay)