This article originally was originally featured by the S. Rajaratnam School Of International Studies and is republished with permission. Read it in its original form here.

By Nilanthi Samaranayake

Synopsis

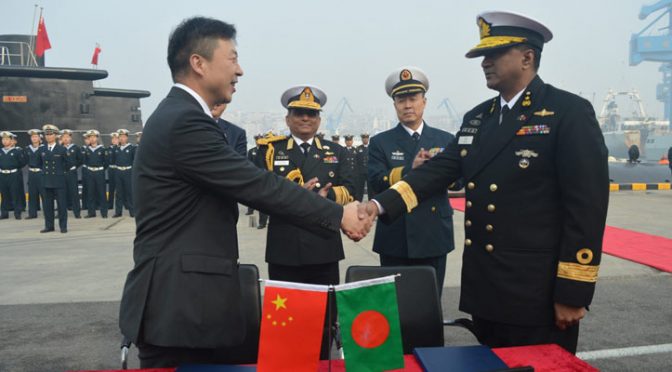

Bangladesh’s acquisition of two submarines from China should not be narrowly viewed through the prism of India-China geopolitics. Rather, it should be understood in a wider context as a milestone by a modernizing naval power in the Bay of Bengal.

Commentary

The impending arrival of two Chinese-origin submarines to Bangladesh together with China’s planned construction of submarines for Pakistan, has contributed to the perception among some observers that China is attempting to encircle India and reinforced concerns about a Chinese “string of pearls.”

Yet Bangladesh’s acquisition of two Ming-class submarines should not be narrowly viewed through this geopolitical prism. Rather, it should be seen in the broader context of the country’s force modernisation, which has important implications for Bay of Bengal security. In fact, Bangladesh’s development of its naval capabilities may contribute as a force multiplier to Indian security initiatives in the Bay of Bengal rather than being a potential threat to regional stability.

Rising Navy

Bangladesh’s latest acquisition has its origins in Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s assumption of power in 2009 and Dhaka’s announced Forces Goal 2030. Under this project, Bangladesh has sought to augment its naval capabilities in “three dimensions,” going beyond solely surface platforms to include a naval aviation wing and undersea leg. Though an ambitious endeavor at the time, by 2011, Bangladesh had established a naval aviation wing by acquiring Italian helicopters and later German maritime patrol craft.

The navy has also expanded its surface fleet through Chinese and U.S. origin platforms. Refurbished submarines from China appear to have been the most competitively priced option to fulfill the third leg of Forces Goal 2030. The announcement about the transfer should be no surprise given that Bangladeshi media and military officers have openly discussed progress toward this goal over the past few years.

Furthermore, Bangladesh is one of a number of countries in the region that are expanding their fleets with sub-surface platforms. Through this force modernisation project, Bangladesh is seeking to be self-reliant and gain prestige for its military, as do many countries with growing economies.

Unsung Contributor to Maritime Security

At the same time that Bangladesh is augmenting its naval capabilities, it is increasing its contributions to maritime security in the Bay of Bengal and beyond. Since 2010, it has deployed two ships to the UN Maritime Task Force off Lebanon. Moreover, having long been a recipient of disaster relief, Bangladesh now seeks to become a provider of such aid. In the past three years, the Bangladesh Navy delivered relief to Sri Lanka after deadly landslides in May, to Maldives after a water crisis in 2014, and to the Philippines after Typhoon Haiyan in 2013.

Bangladesh also seeks a leadership role in advancing international maritime institutions and legal norms. The Bangladesh Navy is currently chairing the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) until 2018. Previously led by the Royal Australian Navy, IONS convenes regional stakeholders to discuss opportunities for cooperation.

At their meeting in January, naval representatives from 30 countries gathered in Dhaka, including the first appearance by a four-star U.S. Navy admiral. Finally, after long-standing maritime disputes with Myanmar and India, Bangladesh opted to use the tools of international arbitration. As a result, the three countries helped affirm the importance of international law in the Indian Ocean.

India: Much to do with Bangladesh

The idea of Chinese sailors training the Bangladesh Navy on submarines in the Bay of Bengal is understandably disconcerting to Indian policymakers. India’s minister of defence recently paid a historic visit to Dhaka to upgrade defence ties, likely aiming to neutralise a long-term Chinese training presence in Bangladesh. Although India’s ability to provide Bangladesh with training on Chinese-origin submarines will be limited, it is an opportune moment for India and Bangladesh to deepen minimal naval cooperation.

Strikingly, neither neighbor engages in bilateral naval exercises or annual navy staff talks; this is a clear area for growth. Both sides make occasional port calls to the other country, the navy chiefs visit each other, and the Bangladesh Navy participates in the Indian Navy’s multinational MILAN maneuvers and in its training schools. The lack of deeper naval interactions may be due to the countries’ maritime boundary dispute, which was not resolved until 2014. A bilateral agreement in 2015 between Sheikh Hasina and Narendra Modi achieved cooperation between the two coast guards, yet not the navies.

As a result of the submarines’ impending arrival, India will be able to seize on this opening to advance naval cooperation, including on this platform. The two nations can develop mechanisms for water-space management and information-sharing in the Bay of Bengal. While Bangladesh will need to train on the submarines for years to develop requisite expertise, it can use this platform to monitor movements and communications as other navies have done.

This will augment maritime domain awareness and may deter criminal activity, including threats posed by Islamist militants. For its part, India houses two military commands in the Bay of Bengal and has a growing anti-submarine warfare capability. Bangladesh’s additional coverage of the maritime domain would supplement efforts to ensure regional stability.

India could also transfer or sell maritime platforms to Bangladesh as it has done for several Indian Ocean countries. As New Delhi tries to increase its indigenous defence industry under the “Made in India” initiative, Indian shipyards, including in nearby Kolkata, could similarly build ships and aircraft for the Bangladesh Navy and Coast Guard.

Way Forward

The delivery of two Chinese submarines to Bangladesh—likely in January or February, according to media reports—represents a milestone by a smaller South Asian country that is modernising its naval forces. Moreover, Bangladesh’s clear contributions to maritime security in the Bay of Bengal and beyond should be encouraged.

India is notably pursuing cooperation on submarines with the United States; it may also find a partner in the undersea domain closer to home. Relations between Dhaka and New Delhi have been growing, especially since Prime Minister Modi’s historic visit in 2015. Bangladesh leader Sheikh Hasina’s upcoming visit would be a good opportunity to lay the foundation for deeper, regular naval cooperation that reduces India’s threat perceptions and develops mechanisms for greater maritime domain awareness. Bangladesh’s evolving naval capabilities and role in advancing international naval operations, forums, and norms can bolster regional maritime security and stability.

Nilanthi Samaranayake is a strategic studies analyst at CNA, a non-profit research and analysis organisation in the Washington, D.C., area. The views expressed are solely those of the author and not of any organisation with which she is affiliated. She contributed this to RSIS Commentary.

Featured Image: Capt. Mohammad Nazmul Karim Kislu leads a formation from the Bangladesh navy during the transfer and decommissioning ceremony of the Coast Guard Cutter Jarvis held on Coast Guard Island, Thursday May 23, 2013. (U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 2nd Class Pamela J. Boehland)