By Conor Kennedy

The role of civilian roll-on/roll-off (RO-RO) ferries in a PLA invasion of Taiwan deserves its growing notoriety. With port access secured or coupled with developing logistics over the shore capabilities, RO-RO ferries could deliver significant volumes of forces across the Taiwan Strait, offsetting shortfalls in the PLA’s organic sea lift.1 Some analysts have even described mobilized civilian assets like RO-ROs as a “central feature of [the PLA’s] preferred approach” to a cross-strait invasion.2

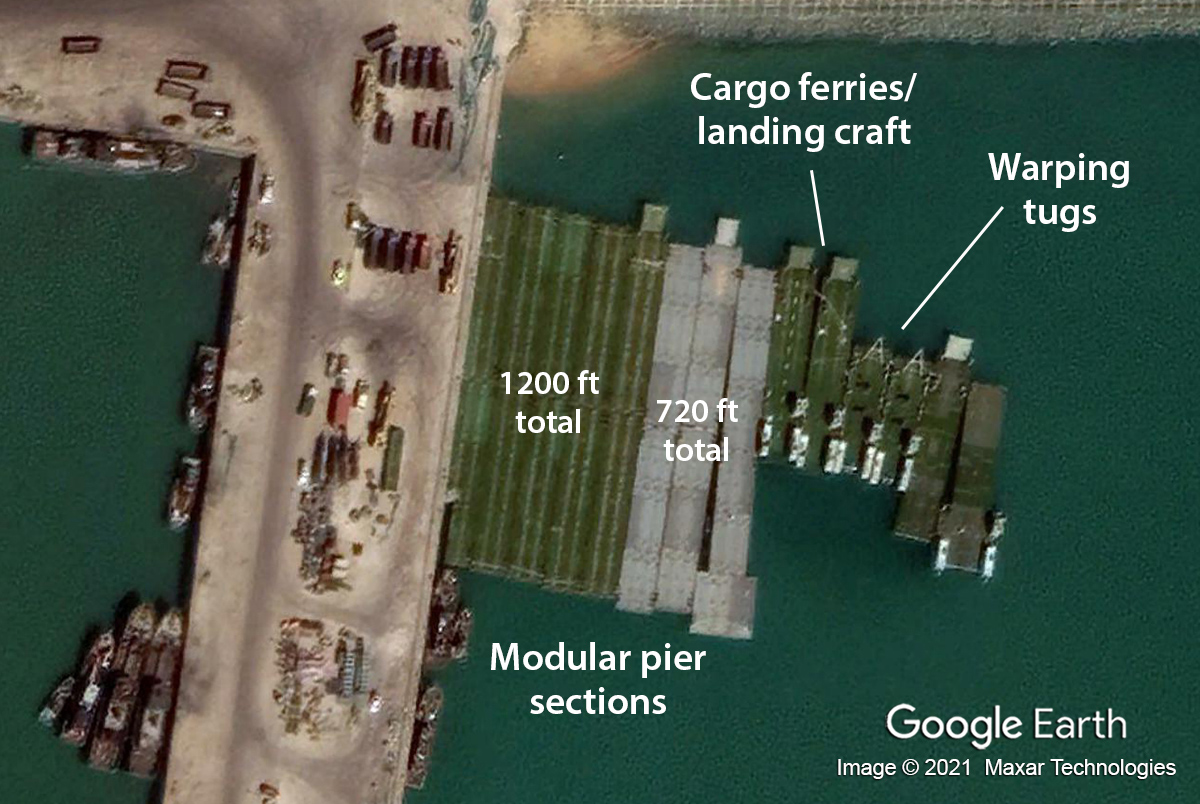

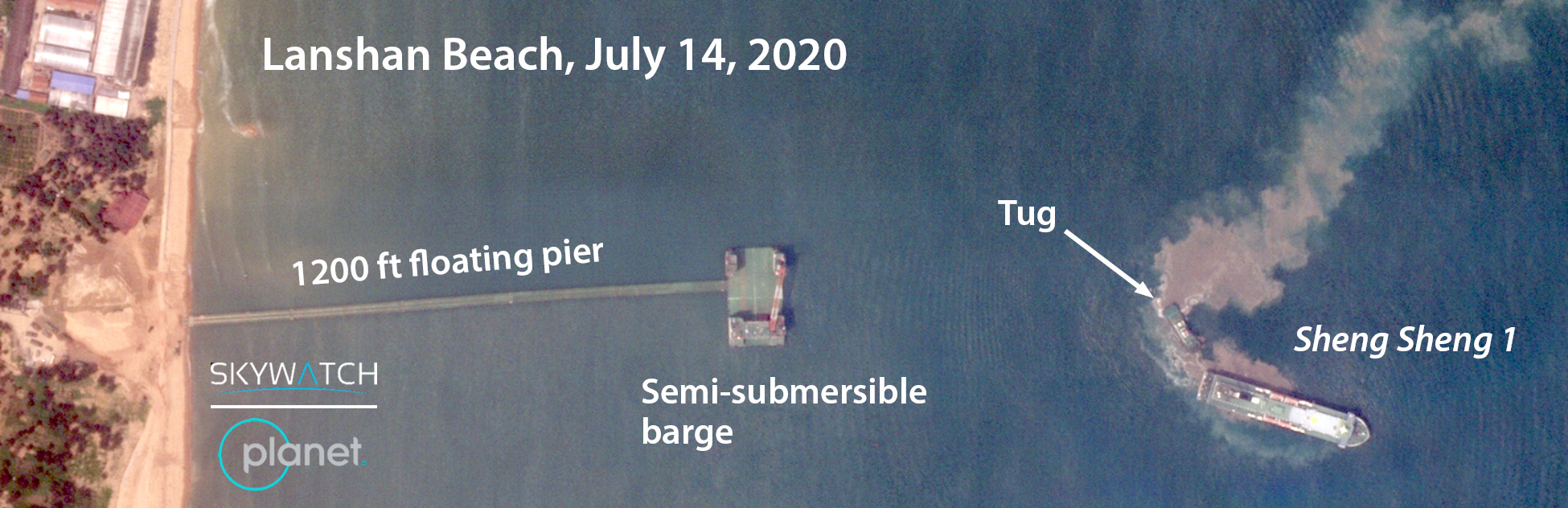

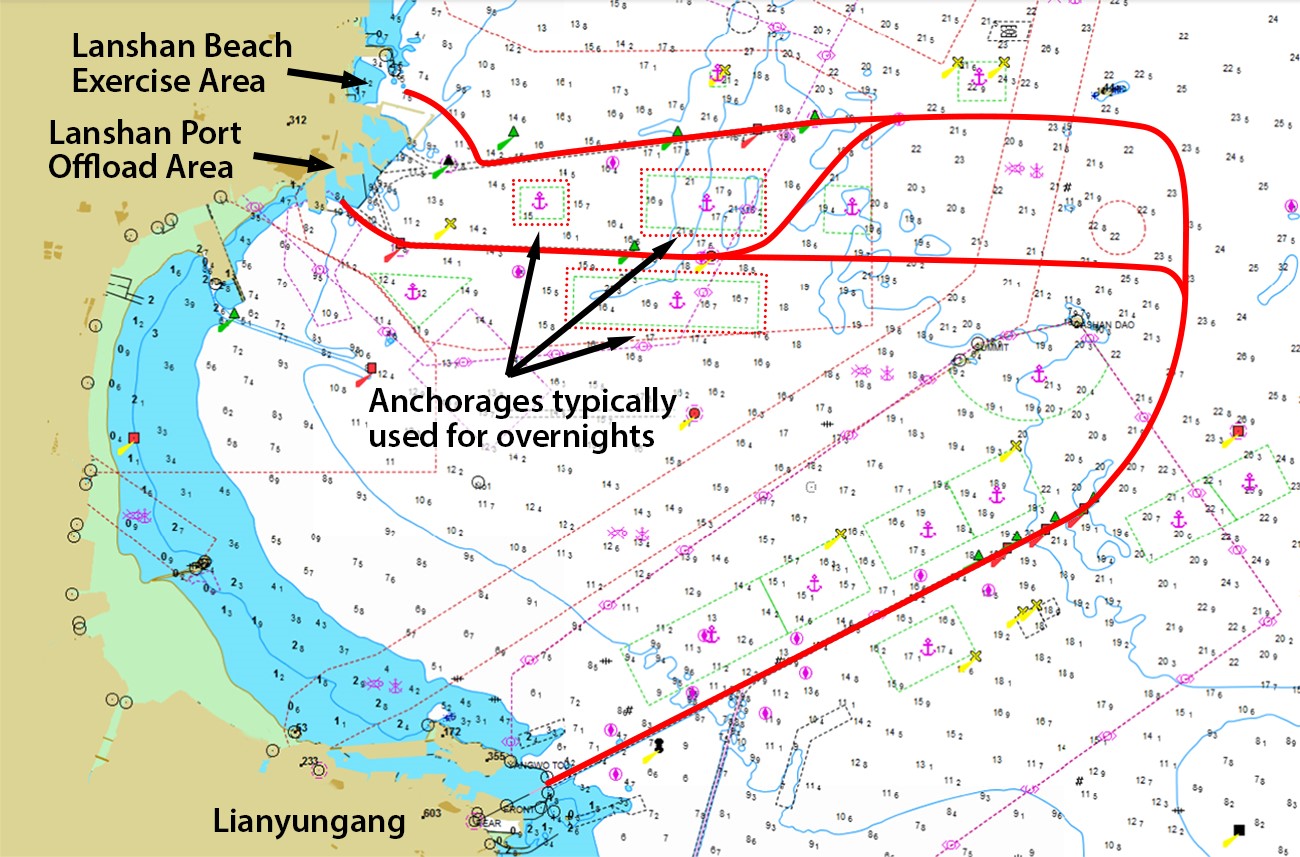

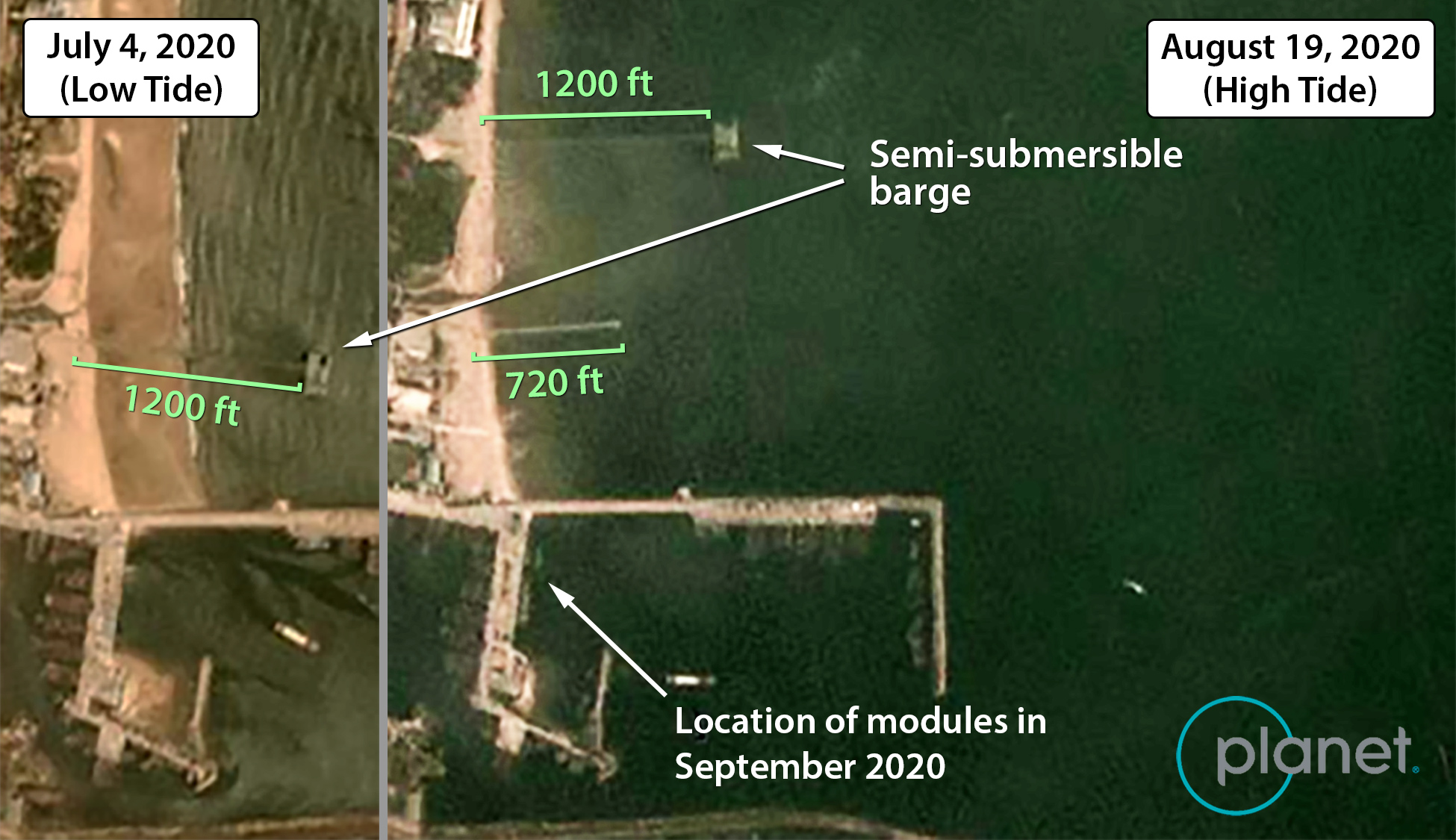

But the PLA appears intent on assigning RO-RO ferries to another mission: launching amphibious combat forces directly onto beaches from offshore. The PLA has long lacked sufficient landing ships to deliver its full complement of amphibious assault forces, from both army and Navy Marine Corps forces, in the initial assault landing on Taiwan. Rather than building numerous grey-hulled traditional landing ships, the addition of RO-RO ferries into a combined landing ship fleet could quickly close this gap.

To make this possible, the PLA has been modifying RO-RO ferries with new stern ramps enabling in-water operations to launch and recover amphibious combat vehicles. The first publicly demonstrated use of the new ramps occurred in 2019 during an exercise involving the 15,560-ton RO-RO ferry Bang Chui Dao, owned and operated by COSCO Shipping Ferry Company and a regular vessel supporting military transportation training exercises. Other ferries have received similar modifications, giving the PLA a significant boost in the total volume of amphibious lift the PLA could muster in a cross-strait amphibious landing.3 This expansion in PLA amphibious capabilities has generated very little attention by the international media despite its clear purpose.

Amphibious warships are optimized for launching and recovering amphibious combat forces, including swimming armor. They feature well decks closer to the waterline, sometimes submersible, making it easier for forces to launch or recover out of the water. The above image depicts a ZBD-05 approaching the LST Wan Yang Shan’s (No. 995) stern gate and illustrates the challenge of RO-RO ferries in conducting amphibious launch and recovery, which feature freight decks much higher above the waterline that are suited to the height of quay walls. Providing ramp strength that can span that distance requires strong hydraulic rams and stays.

COSCO Shipping Ferry Co., Ltd.

The Bang Chui Dao belongs to COSCO Shipping Ferry Co., Ltd., under the state-owned shipping conglomerate COSCO, which operates ten large passenger RO-RO ferries in the Bohai Gulf. COSCO Shipping Ferry has provided service for PLA transportation support for over 25 years.5 It continues to provide its vessels as a “transport group” (海运大队) of the PLA’s strategic projection support shipping fleet (战略投送支援船队), one of many organized within COSCO businesses and other major commercial shippers to support PLA transportation requirements.6

COSCO Shipping Ferry Co. has been developing capabilities for offshore amphibious launch for its ferries over a number of years. In 2016, the company reported having installed a number of new features into four of its ferries, in response to new national defense requirements. The report suggested the Long Xing Dao and the Yong Xing Dao were among the modified vessels, built in 2010 and 2011 respectively. Noted modifications included rapid egress corridors for personnel and some small equipment, measures in compartment design to resist sinking when damaged, and new hydraulically driven systems to enable greater stern ramp extension for moving amphibious armor on and off the vessel at sea.7

The Yong Xing Dao, Long Xing Dao, Hu Lu Dao and the Pu Tuo Dao have each had their stern ramps upgraded within the past couple of years. These ramps likely utilize the same mechanical principle behind that used for the Bang Chui Dao. Structurally, they appear stronger, longer, and are actuated by heavier-duty hydraulic rams. Noticeably, the ramps are flanked by large, multi-hinged steel support arms that act as preventer stays to maintain ramp rigidity when under tension by the hydraulic rams. These are mounted externally as shown below. The Bang Chui Dao’s ramp-mounted hydraulic assemblies had similar preventers but were mounted internally due to the lack of room between the stern ramp and the quarter-stern ramp.

Some modified ramp systems will not be permanent installations. For example, recent public footage of the Bang Chui Dao indicates the ramp featured in the 2020 PLAN Marine Corps exercise was removed, and the regular commercial service ramp reinstalled. While suited for launching amphibious armor, the modified system clearly reduced the horizontal clearance of the stern ramp and would not be practical for commercial operators that need to accommodate various sizes of vehicles and trucks. Thus, the PLA likely has these systems held in storage to be installed on vessels like the Bang Chui Dao and the Hai Yang Dao, which features the same quarter-stern ramp, when needed.

Observations of vessel activities also indicate additional COSCO ferries have been similarly modified. In two recent reports, Michael J. Dahm found the Hu Lu Dao took part in amphibious landing training exercises in July 2021, and the Chang Shan Dao in July 2022.8 This implies at least seven COSCO passenger RO-RO ferries have the ability to conduct offshore launch of amphibious combat forces.

Conversions to BH Ferry Group

Ramp conversion practices have matured enough for wider application in other companies. This is evident within the Bohai Ferry Group, a RO-RO shipping company also concentrated in the Bohai Gulf and comprising the Eighth Transport Group.9

Over the last 15 years, Bohai Ferry Group has expanded its fleet and its cooperation with the PLA.10 The company began implementing national defense requirements in new vessel construction when the former Jinan Military Region Military Transportation Department participated in the design of the 36,000-ton class of ferries starting in 2010 with the Bohai Cuizhu. With inputs from regional military units regarding equipment requirements, the new ferries received helicopter pads, reserve medical spaces, improved command and communications equipment, greater freight deck ventilation, improved firefighting systems and other features.11 While some modifications are difficult to observe directly, some of the latest ramp conversions are readily apparent.

At some point in the last two years, Bohai Ferry Group modified the stern ramps on four of its 36,000 gross-ton ferries, the Bohai Mazhu, Bohai Cuizhu, Bohai Jingzhu, and Bohai Zuanzhu. Specifically, large hydraulic assemblies have been installed on the transom flanking the stern ramp. Similar to the Bang Chui Dao’s assembly, heavy-duty hydraulic cylinders will be released from their secured positions and assisted via a smaller hydraulic ram into a set of clevis brackets affixed to the ramp. As designed, this new position allows for further depression of the ramp into the water, and thus the launch of amphibious combat vehicles.

These new systems are also operational in recent PLA amphibious exercises, deploying and recovering amphibious forces from offshore, as documented by Dahm. Participation of all four of the 36,000 gross ton class, as well as the 24,777 gross ton multi-purpose ferry Bohai Hengtong was observed in late summer exercises of 2021 and 2022.13 The Bohai Hengtong’s stern ramp is likely long enough for amphibious launch, but may require additional ramp-mounted support due to the presence of the vessel’s quarter-stern ramp. The specific ramp modification for this vessel or its sister ship the Bo Hai Heng Da is unclear.

Implications

These modifications to civilian RO-RO ferry ramps have the potential to significantly augment the PLA’s access to amphibious lift. The ferries previously identified contain the following lane in meter (LIM) dimensions and deadweight tonnage (DWT – i.e., a ship’s total carrying capacity) which can help analysts determine the total volume of amphibious combat forces they can add to the PLAN’s organic amphibious lift.

RO-RO Ferries Likely Capable of Offshore Amphibious Launch/Recovery (as of February 2, 2023)

| Vessel Name | Conversion Method | DWT | LIM |

| Bohai Cuizhu (渤海翠珠) | Permanent external installation | 7,587 | 2,500 |

| Bohai Jingzhu (渤海晶珠) | Permanent external installation | 7,598 | 2,500 |

| Bohai Mazhu (渤海玛珠) | Permanent external installation | 7,503 | 2,500 |

| Bohai Zuanzhu (渤海钻珠) | Permanent external installation | 7,481 | 2,500 |

| Bohai Hengtong (渤海恒通) | Unknown | 11,288 | 2,700 |

| Yong Xing Dao (永兴岛) | Permanent installation | 7,662 | 2000 |

| Long Xing Dao (龙兴岛) | Permanent installation | 7,743 | 2000 |

| Chang Shan Dao (长山岛) | Likely permanent installation | 7,670 | 2000 |

| Pu Tuo Dao (普陀岛) | Permanent installation | 3,996 | 835 |

| Hu Lu Dao (葫芦岛) | Permanent installation | 3,873 | 835 |

| Bang Chui Dao (棒棰岛) | Requires internally-mounted system | 3,547 | 835 |

| Hai Yang Dao (海洋岛) | Requires internally-mounted system | 3,547 | 835 |

| TOTAL | 79,495 | 22,040 |

Note: Most of the modified vessels included in this table have been visually confirmed through openly available imagery and video sources online.

While simply dividing each vessel’s deadweight tonnage by vehicle weights can yield hundreds of vehicles per vessel, the impressive advertised carrying capacities of these ships do not translate directly into the volume of PLA forces they can transport. Crew, passengers, fresh water, fuel, and other various cargo will take up some of the deadweight tonnage listed above, and the remainder will be portioned out to vehicles, as permitted by the total vehicle lane space. Other basic characteristics such as the spacing of vehicle tie down anchor points in vessel decks will also be important factors in determining capacity.

Internal spatial dimensions and freight deck strength will better determine what kind of vehicle and how many can load. PLA transportation experts find that most of China’s RO-RO passenger ferries feature 3.1-meter wide vehicle lanes, which do not satisfy the width requirements for large numbers of tracked armored vehicles. In addition to not optimizing occupied deck space, improper positioning of heavy loads outside of vehicle lanes could also result in damage to freight decks. Additional internal clearance constraints along ramps and elevators will also limit what types of vehicles and cargo are stowed on each deck, likely only permitting the heaviest armored vehicles, such as main battle tanks, on the main freight decks.14 For example, the four 36,000-gross ton Bohai Ferry Group ferries each have 2,500 total LIM. Despite this impressive volume, PLA experts have noted limitations in their ability to carry large, armored vehicles.

The Bohai Mazhu, the last of the four to enter operation in April 2015, has internal ramp widths of 3.5m and elevator widths of 3m, limiting heavy tanks to only the main freight deck.15 It is likely the Bohai Mazhu’s preceding sister ships also feature the same limiting dimensions. These issues impact transport of the PLA’s heaviest equipment but could also limit their ability to transport amphibious combat vehicles such as the Type-05 series of vehicles. Boat-like in its hull design, a ZBD-05 has a reported width of 3.36 meters and length of 9.5 meters, which could cause difficulty in making turns and accessing upper or lower decks.16 Other vessels may be more accommodating. For example, the Chang Shan Dao reportedly has a 3.6 m-wide elevator and 3.5 m-wide internal ramps, as may its sister ships, the Yong Xing Dao and Long Xing Dao.17

More importantly, while total loading capacities may be useful for gauging how the PLA might optimize its loading plans for relatively secure terminal to terminal delivery operations, offshore amphibious launch entails very different considerations. The stowage of amphibious combat forces will likely be done according to combat loading plans that do not emphasize the maximization of forces occupying deck space. Instead, forces would load according to their assigned assault waves, which likely include both armor and infantry aboard assault craft, and other support elements. Each wave must be positioned and readied to access and launch from the vessel’s stern ramp.

Moreover, launching amphibious combat forces brings vessels closer to active combat areas. The threat of adversary attacks could lead the PLA to disperse forces across many ships. Multiple units confined to a single ferry could be a vulnerability demanding more protection of that single vessel. It is likely that ferries participating in this mission will not be loaded to the brim. As pure transporters, they may seek to launch forces as quickly as possible to reduce their own exposure and swiftly return to ports of embarkation to load follow-on forces.

Despite this, these vessels offer a significant additional source of amphibious lift for the PLA, especially for delivery of first echelon amphibious combat forces critical to securing areas for landing the follow-on invasion force. With the previously-mentioned spatial limitations in mind, a conservative estimate of the total capacity of the ships identified in this article adds on capacity sufficient for half the PLA army’s primary amphibious combat forces (12 amphibious combined arms battalions).18 This places one battalion on each vessel, with room for additional supporting elements from their respective brigades. Depending on internal space constraints, vessels like the Pu Tuo Dao could probably deliver a single battalion, while some of the larger vessels could likely carry up to two battalions if the PLA accepts the risk. Having fewer forces embarked would also make it easier for these vessels to support forces loaded well in advance of an invasion, as many ferries market to tourists their berthing compartments complete with toilets and showers, and feature mess halls and recreational facilities. Spare vehicle deck space could also be employed to support embarked amphibious units. If done right, such early loading could relieve pressure on PLA loading operations, but also make detecting a force build up more difficult.

Conclusion

The PLA has rapidly expanded its landing ship fleet over the last few years. It has not taken the form many may have expected, such as the construction of numerous naval landing ships, instead focusing efforts on civilian RO-RO ferries to fulfill the PLA’s requirements. This article set out to identify the PRC-flagged RO-RO ferries with ramps that can enable offshore amphibious launch. It has likely failed to enumerate all the various ramp configurations and identify all the vessels involved.

Both COSCO Shipping Ferry Group and Bohai Ferry Group have ferries capable of supporting this mission. Some ramp systems are temporary, suggesting preparations for some ferries to rapidly refit when needed, while others are permanent observable installations. The ferries themselves are dual-commercial and military use ships, however, their ramp modifications have a sole purpose, the offshore launch of amphibious combat forces in a landing operation against Taiwan. Furthermore, these capabilities are not simply theoretical, as some of these ships take part in landing exercises with PLA amphibious ground units.

The PRC appears to have significantly expanded its amphibious lift capacity with little notice from the international community, much less criticism. While many PLA experts write openly on the important roles of the commercial RO-RO fleet in a cross-Strait invasion, specifically their roles in transporting large volumes of heavy follow-on forces, they have generally steered clear of discussing their role in offshore amphibious launch. If these RO-RO modifications and their application in military exercises are observable by a foreign audience, they should be readily known by PLA military transportation professionals. This supports the author’s original assertion in 2021 that this expansion in capacity could occur quickly and quietly.

There are still many more questions to be answered regarding the effectiveness of this approach. The PLA must tackle coordination between the joint forces, including organic landing ships and civilian assets. There are organizational, command and control, communications, security, and numerous other issues to solve before RO-RO ferries can effectively support a joint island landing campaign, especially if they are to join in delivering landing assault waves. Nonetheless, an initial understanding of the scale of this approach is important for gauging the significance of its contribution toward delivering the PLA’s joint landing forces.

Conor Kennedy is a research associate in the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute in Rhode Island.

The analyses and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Navy or the U.S. Naval War College.

Endnotes

1. For an analysis of a PLA invasion against port locations, see: Ian Easton, Hostile Harbors: Taiwan’s Ports and PLA Invasion Plans,” Project 2049 Institute, July 22, 2021, https://project2049.net/2021/07/22/hostile-harbors-taiwans-ports-and-pla-invasion-plans/; For an analysis of PLA logistics over the shore capabilities, see: Dahm, J. Michael, “China Maritime Report No. 16: Chinese Ferry Tales: The PLA’s Use of Civilian Shipping in Support of Over-the-Shore Logistics” (2021). CMSI China Maritime Reports. 16. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports/16; and “China Maritime Report No. 25: More Chinese Ferry Tales: China’s Use of Civilian Shipping in Military Activities, 2021-2022” (2023). CMSI China Maritime Reports. 25. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports/25.

2. Henley, Lonnie D., “China Maritime Report No. 21: Civilian Shipping and Maritime Militia: The Logistics Backbone of a Taiwan Invasion” (2022). CMSI China Maritime Reports. 21. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports/21.

3. Conor Kennedy, “Ramping the Strait: Quick and Dirty Solutions to Boost Amphibious Lift,” China Brief, Volume 21, Issue: 14, https://jamestown.org/program/ramping-the-strait-quick-and-dirty-solutions-to-boost-amphibious-lift/.

4. 严家罗, 周紫春, 周启青 [Yan Jialuo, Zhou Zichun, Zhou Qiqing], 海军陆战队某旅海上浮渡装卸载训练 [“A Navy Marine Corps Brigade in Afloat Loading and Unloading Exercises”], 当代海军 [Navy Today], No. 7, 2015, p. 31.

5. 潘诚, 王正旭 [Pan Cheng, Wang Zhengxu], 沈阳联勤保障中心某航务军代处与企业共同制定军运细则 [“A Shenyang Joint Logistics Support Center Navigational Military Representative Office Jointly Formulates Military Transportation Rules with an Enterprise”], 中国国防报 [China Defence News], June 15, 2017, p. 3, http://www.81.cn/gfbmap/content/21/2017-06/15/03/2017061503_pdf.pdf.

6. Conor M. Kennedy, “China Maritime Report No. 4: Civil Transport in PLA Power Projection” (2019). CMSI China Maritime Reports. 4. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports/4.

7. 王正旭, 高勇, 贾文暄 [Wang Zhengxu, Gao Yong, Jia Wenxuan], 客轮首尾开门运兵运超重军事装备 可起降直升机 [“Passenger Ships Carry Troops and Overweight Military Equipment, and Can Land Helicopters”], 中国国防报 [China Defence News], September 29, 2016, https://www.chinanews.com.cn/mil/2016/09-29/8018481.shtml.

8. Dahm, J. Michael, “China Maritime Report No. 16: Chinese Ferry Tales: The PLA’s Use of Civilian Shipping in Support of Over-the-Shore Logistics” (2021). CMSI China Maritime Reports. 16. pp. 33-38,

https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports/16; Dahm, J. Michael, “China Maritime Report No. 25: More Chinese Ferry Tales: China’s Use of Civilian Shipping in Military Activities, 2021-2022” (2023). CMSI China Maritime Reports. 25. Pp. 34-36,

https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports/25.

9. 李远星, 王丙 [Li Yuanxing, Wang Bing], 新时代战略投送支援力量建设运用研究 [“Research on Construction and Use of Strategic Projection Support Forces in the New Era”], 国防 [National Defense], No. 12 (2017), 20–23.

10. Since 2006, Bohai Ferry Group has constructed over 16 large RO-RO ferries ranging from 20,000 to 45,000 gross tons. See: 关于我们 [“About Us”], 渤海轮渡集团股份有限公司 [Bohai Ferry Group Co., Ltd.], Undated, http://www.bhferry.com/brief.html

11. 李响 [Li Xiang], 军民融合领域的一次成功实践: “渤海翠珠” 滚装船提升我军海上战略投送能力纪实 [“Record of a Successful Practice in Civil-Military Fusion: the RO-RO Ship ‘Bohai Cuizhu’ Enhances Our Military’s Maritime Strategic Projection Capabilities”], 国防科技工业 [National Defense Science and Technology Industry], No. 1 (2012), 53.

12. 建设打仗后勤 [“Building Warfighting Logistics”], CCTV –《追光》[CCTV- Chasing the Light], Episode 11, October 9, 2022, https://tv.cctv.com/2022/10/09/VIDErLF38LiQWiL4DD2eu0UM221009.shtml?spm=C55953877151.PmHVnEZCnjLh.0.0

13. Dahm, “China Maritime Report No. 16,” pp. 33-39; Dahm, “China Maritime Report No. 25,” pp. 36-44; For an image depicting the Bo Hai Heng Tong launching vehicles, see: H I Sutton and Sam LaGrone, “Chinese Launch Assault Craft from Civilian Car Ferries in Mass Amphibious Invasion Drill, Satellite Photos Show,” USNI News, September 28, 2022, https://news.usni.org/2022/09/28/chinese-launch-assault-craft-from-civilian-car-ferries-in-mass-amphibious-invasion-drill-satellite-photos-show

14. 孙琪, 刘宝新 [Sun Qi, Liu Baoxin], 民用客滚船军事应用研究 [“Research on Military Application of Civil Ro-Ro Passenger Ships”], 军事交通学报 [Journal of Military Transportation], No. 2, 2022, p. 26.

15. Ibid.

16. “ZBD-05 or VN-18,” Army Recognition, July 9, 2021, https://www.armyrecognition.com/china_chinese_light_armored_armoured_vehicle_uk/zbd-05_zbd05_zbd2000_amphibious_armoured_infantry_fighting_vehicle_data_sheet_specifications.html;

17. 吴克南 [Wu Kenan], 我国滚装船运输军事重装备的适用性研究 [“The Applicability Research of China Ro-Ro Ship Used to Transport Military Heavy Equipment”], 大连海事大学-硕士学位论文 [Dalian Maritime University – Master’s Thesis], March 2016, p.

18. This is based on the estimated size of an army amphibious combined arms battalion consisting of 80 vehicles and 500-600 troops. See: Blasko, Dennis J., “China Maritime Report No. 20: The PLA Army Amphibious Force” (2022). CMSI China Maritime Reports. 20, pp. 3-4. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports/20.

Featured Image: A CCTV report showed a cargo ship that was being used to carry troops, weapons and supplies in a recent PLA exercise. (Photo via CCTV)