By Dirk Steffen

2016 witnessed a marked increase in maritime security incidents over the previous year, irrespective of the counting standards. Denmark-based Risk Intelligence counted 119 verified attacks by criminals on all kinds of vessels in West Africa (Senegal to Angola) – compared with 82 in 2015. The vast majority of attacks in 2016 were perpetrated by Nigerian criminals, including all of the 84 that were concentrated in and around Nigerian waters.

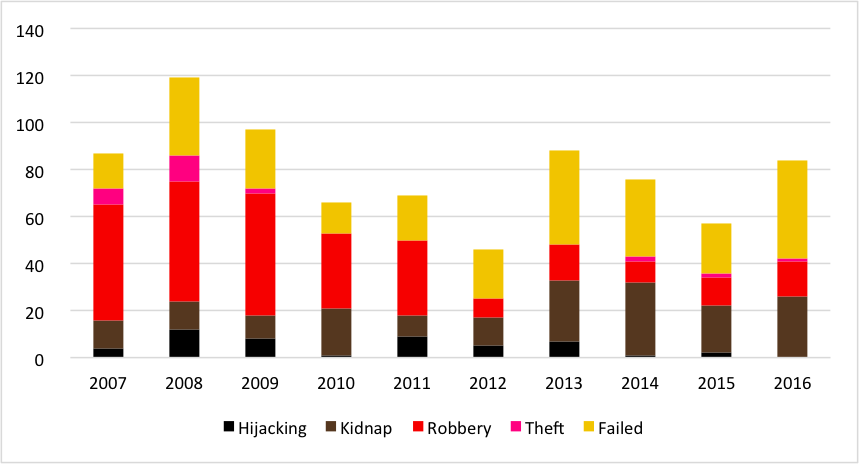

However, as alarming as such figures may seem, 2016 was neither unusually busy nor were there any significant changes to the patterns of maritime crime in West Africa, specifically the Gulf of Guinea, when assessed in the long term. Over a 9-year period (since 2007), the average number of maritime security incidents for West Africa is 122 – typically ranging between 80 and 140 per year. Of this figure, Nigerian waters alone account for an average of 87 attacks per year.

Throughout this period, maritime kidnappings steadily increased and focused almost exclusively on Nigerian waters. Since 2013, maritime kidnappings have accounted for around 30 percent of all attacks (including failed attacks) off Nigeria. In 2016, most successful kidnappings were concentrated in two cycles of attacks: the first in January to mid-May 2016 (mirroring almost exactly the development of 2013), the second in the last two months of the year. Hijackings, a common feature during the MEND insurgency in the Niger Delta between 2006-2009, and again during the period of tanker hijackings between late 2010 and 2013, have all but stopped, following the successful intervention of the Nigerian Navy against the hijackers of the tanker MAXIMUS in February 2016.

The real strategic concern for the Nigerian government in 2016 was the resurgent Niger Delta insurgency. It was spearheaded by a group called the “Niger Delta Avengers,” whose campaign of oil and gas infrastructure disruption reduced the Nigerian oil output to a historic low of 1.1m barrels per day (bpd) (vis-à-vis the projected 2.2-2.4m bbpd and the average 1.75m bbpd on average in 2015) during the summer of 2016. One impact on maritime security was the disruption of crude oil loading and an increased demand for petroleum products (due to Nigerian refineries being cut off from their crude oil supplies), thus creating, at least in theory, a more target-rich environment. However, the dynamics of maritime insecurity in Nigeria are historically driven by other factors. As the insurgency went through its customary cycles of issuing threats, militant action, and “cease-fires” to regroup and reiterate demands, the maritime security situation displayed an inverse correlation: the spate of attacks reminiscent of the first 4 months of 2013 swept across the seas off the Niger Delta between March and mid-May 2016, followed by a lull as militant groups were actively engaged in onshore violence throughout the summer. Offshore attacks returned to the waters outside the Niger Delta in November and December 2016 because of calmer weather, cyclical pre-Christmas criminal activity, and lower onshore militancy. This pattern suggests that at the tactical level, the “attackers” ,when not employed in militancy, oil theft, illegal bunkering or gang warfare, engage in piracy to cover some of their funding needs.

The wider Gulf of Guinea was less affected by these developments than it was when the tanker hijackings originating from Nigeria peaked in 2011-12. While the capability to enforce security even in very limited parts of their territorial waters remains constrained for some nations, like Congo, Sao Tome and Principe, Liberia or Sierra Leone, organized piracy has not really taken hold in any of those places. In Guinea-Conakry, however, members of the armed forces are engaged in armed robbery at sea and extortion of foreign fishing vessels, even in neighboring Sierra Leone. Ghana experienced a spate of petty thefts at Takoradi anchorage, which gave it some bad press, but no violence against crews was reported. By and large, when speaking of “Gulf of Guinea piracy” as a problem for international shipping, it is Nigerian piracy that we mean. Other forms of maritime crime, on the other hand, such as illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU), smuggling of oil, drugs, agricultural products and other goods were – and are – the more pressing day-to-day challenges for coastal nations in the region.

It is important to understand that many acts of Nigerian “piracy” also have a hidden context that the uncritical reporting in the international press is unaware of. Locally trading product tankers are often attacked, and crew members kidnapped or cargo stolen, as a part of criminal “turf” wars or other disputes between criminal parties. The kidnapping of crew members from fishing (and refrigerated cargo) vessels is often related to extortion within the criminal business of illegal fishing and transhipment of catch. This may, for example, have been the case on 27 November 2016, when the SARONIC BREEZE was attacked 80 nm off Cotonou. The Panama-flagged vessel, according to the Benin Navy, was in a different place than where it should have been (at the anchorage) when it was attacked and three crew members kidnapped.

Regional Cooperation

Against this slightly disconcerting backdrop, there is the gradual increase of political will and ability by some West African nations to take ownership of maritime security. Following the successful rescue of the MAXIMUS, the Nigerian Navy launched Operation ‘Tsare Teku’ in the face of intense pirate activity, and prolonged the operation throughout summer, while being engaged in counterinsurgency operations at the same time. While the impact of the operation was assessed as modest even by Nigerian planners, it demonstrated that the Nigerians were, for the first time, publicly owning up to the problem of maritime piracy emanating from their country. More recently, the flag officer commanding the Eastern Naval Command, Rear Adm. James Oluwole, quite rightly pointed out that the lack of prosecution reduced any effectiveness the Navy might have in the battle against maritime criminals.

The lack of prosecution, and in many cases the lack of legislation that permits prosecution of pirates, is still one of the shortfalls of the implementation of the Yaoundé Code of Conduct as it came under review in mid-2016, when its initial three-year trial period ended. Information sharing, maritime domain awareness, and maritime law enforcement capacities and capabilities vary sharply throughout the region, and are by and large wholly insufficient, although measurable progress has been made in all fields. Nigeria, as the main country of origin for serious criminals in maritime piracy, is in the process of passing a law that will allow it to prosecute pirates who had hitherto gone unpunished or were indicted for lesser crimes.

The Role of Private Maritime Security

Gulf of Guinea states remain wary of private security solutions, yet various models of private-public security partnerships exist in the region. In Benin and Togo, both navies operate “secured anchorages,” in addition to providing embarked teams of navy troops through agents and local security companies. In Ghana and Cameroon, naval or, in the case of Cameroon’s Battalion d’Intervention Rapide (BIR), army protection can be obtained through direct liaison with those nations’ militaries.

The most unusual arrangement though has evolved in Nigeria. Although various models have been employed by security companies and shipping companies, not always with authorization by the Nigerian government, the pre-eminent security solution is the security vessel or patrol boat. Security vessels have a long history that date back to the early 2000s, when the first armed unrest spread onto the creeks and off the Niger Delta. Typically, the security vessels of that era were ordinary offshore support vessels with four to six embarked soldiers. These vessels were (and still are) predictably ineffective against groups of heavily armed attackers, who engage with two to three large speedboats, often with one or two general purpose machine guns between them.

The model of choice though, originally conceived at the height of the Niger Delta insurgency between 2006 and 2009, was for private companies to supply and maintain patrol boats, which would be put at the disposal of the then dysfunctional Nigerian Navy. When not on military business, those vessels and their Nigerian Navy gun crews with mounted weapons and ammunition would be available for protection missions for commercial clients. Sixteen Nigerian companies entered such an agreement with the Nigerian Navy in 2016 under a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), effectively providing the bulk of offshore oil field security, and increasing the amount of merchant vessel protection in- and outbound from Nigerian ports. A privately operated joint venture also manages the secure anchorage off Lagos, the only such dedicated area in the region officially promulgated on admiralty charts.

More than 100 such privately contracted security vessels are in operation in Nigerian waters. No one knows the exact number – not even the Nigerian Navy. The quality of these vessels varies – ranging from purpose-built law-enforcement and patrol boats to hastily converted offshore support vessels (or vessels with embarked troops only.) While this contractor fleet provides a welcome relief for the Nigerian Navy, which has only a few assets capable of patrolling the exclusive economic zone, it also presents a major headache for the Nigerian Navy’s operations department to monitor the activities of these contracted patrol boats and supply men, weapons, and ammunition to them and ensure compliance with the terms of the MoU.

The document envisages a partnership between the Nigerian Navy and the private companies for maintenance, training, welfare, and information sharing, thus leveraging the Navy’s “investment” in terms of hard-to-get trained personnel and weapons into the public-private partnerships. Unfortunately, most companies appear to consider the partnership as an “optional” element of their relationship with the Navy. This is compounded by commercial and contractual pressures that preclude many security vessels from rendering assistance to attacks or incidents other than those involving their clients. Unless the MoU is enforced more rigorously, it is therefore unlikely that anyone except for a handful of commercial clients with sufficiently deep pockets will benefit from this arrangement.

Conclusion

Despite the brief surges of offshore piracy in 2016, the Gulf of Guinea remains “business as usual” in terms of maritime security, with incidents in Nigerian waters or emanating from Nigeria accounting for the lion’s share of incidents. For the other West African countries, with a few exceptions, piracy is persistent, but one of the lesser problems in a region characterized by weak maritime governance.

For Nigeria, 2016 was one of the hardest years since the county’s return to democracy in 1999, politically and economically. While the “Niger Delta Avengers” failed to incite a broad-based insurgency in the Niger Delta, their pinpoint targeting of critical oil and gas infrastructure in the Niger Delta was more effective than MEND ever was in that respect; even the temporary loss of control of considerable territory in the northeast to Boko Haram in 2013-14 was strategically less significant.

The onshore security situation in the Niger Delta had a direct impact on the maritime security situation in Nigerian waters and the wider Gulf of Guinea. The seesaw between onshore violence and surges of offshore piracy underlines that while Buhari and his government have made some inroads against the “godfather” system, the latter is far from defeated. It continues to bind criminal, economic, and political interests in Nigeria together. Nigeria will thus remain the nexus for organized crime in western Africa and any regional efforts can only contain the maritime element of this threat until the problem is solved in Nigeria.

Private maritime security will likely remain the (expensive) sticking plaster to fix the situation for commercial ship operators in the short term. However, few of the models in use, short of purpose-built and suitably armed patrol boats, are likely to provide any meaningful deterrent against Nigerian pirates in particular, who are both capable and willing to overcome armed resistance. Except for Ghana and Cameroon (where the use of naval/army assets for commercial purposes is severely circumscribed), none of the “private” or public-private maritime security solutions is likely to enhance the scarce maritime security assets and capabilities of the West African nations.

Dirk Steffen is a Commander (senior grade) in the German Naval Reserve with 12 years of active service between 1988 and 2000. He took part in the African Partnership Station exercises OBANGAME EXPRESS 2014, 2015 and 2016 at sea and ashore for the boarding-team training and as a Liaison Naval Officer on the exercise staff. He is normally Director Maritime Security at Risk Intelligence (Denmark) when not on loan to the German Navy. He has been covering the Gulf of Guinea as a consultant and analyst since 2004. The opinions expressed in this article are his alone, and do not represent those of any German military or governmental institutions.

Featured Image: A Nigerian Marine Police checkpoint on the Bonny River designed to intercept illegally refined petroleum products from being marketed in Port Harcourt. Endemic corruption in Nigeria’s police force casts some doubt on the effectiveness of such measures. Photo: Dirk Steffen.