Scarborough Fair

While no longer making regular headlines, the stand-off over the Scarborough Shoal/Panatag Shoal/Huangyan Island continues. Since April 10th both China and the Philippines have maintained a presence in the area, but one limited to civilian agencies – the Philippines Coast Guard on one side, and the Chinese Maritime Surveillance agency on the other.

Rather than trading literal broadsides, China and the Philippines have fought this dispute mostly through the figurative variety in the diplomatic and economic spheres. Philippines President Benigno Aquino suggested exploring joint ventures in the area and sent envoys to Beijing to attempt to resolve the crisis. China meanwhile issued travel advisories for the Philippines, halted tours, scaled back commercial flights, and quarantined incoming Philippine bananas on pest-control grounds.

Both nations have issued fishing bans on the Shoal area in the past week. The Chinese most likely issued the ban because their own fishermen will stay away until monsoon rains abate in the fall, and the stay-behind surveillance ship snow have a pretext in the ban for enforcement. The Philippines, meanwhile, supposedly issued their own ban in order to protect depleted fishing stocks, but this adversely affects the economies of local fishing communities that depend on fishing the Shoal grounds year-round to make their livelihoods.

With personal financial stability and pride at stake, it’s no surprise that civilians at times seem readier to push the situation towards a conflict than the two nations’ governments. In addition to the wide-spread nationalism (and minor protest rallies) whipped up on both sides and given voice in online forums, some 20 protestors and camera crew planned to make the case for the Philippines by setting up a protest on the shoal itself. They were persuaded by President Aquino to allow the government negotiators in Beijing a chance to achieve a constructive outcome.

Despite what my colleague believes about the benefits of the U.S. sitting on the sidelines of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, the Scarborough Shoal stand-off is an apt example of how not having ratified the treaty can hamstring the U.S.’ ability to bring pressure to bear on another country (China) for failing to live up to its treaty obligations in pursuance of a peaceful and diplomatic resolution. For while the Philippines is building a case for the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), one of the UNCLOS conflict-resolution mechanisms, China, another signatory, refuses to abide by any rulings of the tribunal.

With the stand-off as a backdrop, both sides are expanding their naval forces. The Philippine navy is set to take possession of another U.S. Coast Guard vessel Tuesday, the ex-USCGC Dallas, of the same type as its current flagship, the BRP Gregorio del Pilar. The Chinese Maritime Surveillance administration is also rapidly expanding in numbers (h/t Chuck Hill – CGBlog.org). This is the agency that intervened at the Shoal and prevented the Philippine navy from arresting the Chinese fisherman whose discovery began the current stand-off. While a nation with an expansive coastline and far-flung fishing interests has legitimate needs for a competent coast guard, the continuing Scarborough Shoal stand-off is just one more illustration that ships of this agency are enforcers of state policy, and Chinese maritime state policy has been rather uncompromising of late.

Law of the S.E.A.

With the recent statements from U.S. Secretary of Defense Panetta and the U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) advocating the ratification of the three decade-old UN Law of the Sea Convention (UNCLOS), it is clear that U.S. policy will continue to support a cooperative approach to maritime security. Besides Secretary Panetta’s detailed justification for UNCLOS in providing “economic jurisdiction” and a seat at the table (sans hypocrisy) for future international maritime dispute resolutions, UNCLOS supports freedom of navigation and access to the global commons (unless restricted by historical treaties such as the Montreux Convention).

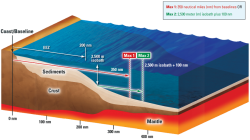

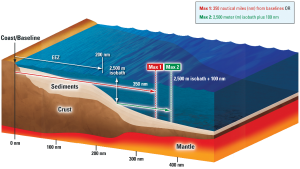

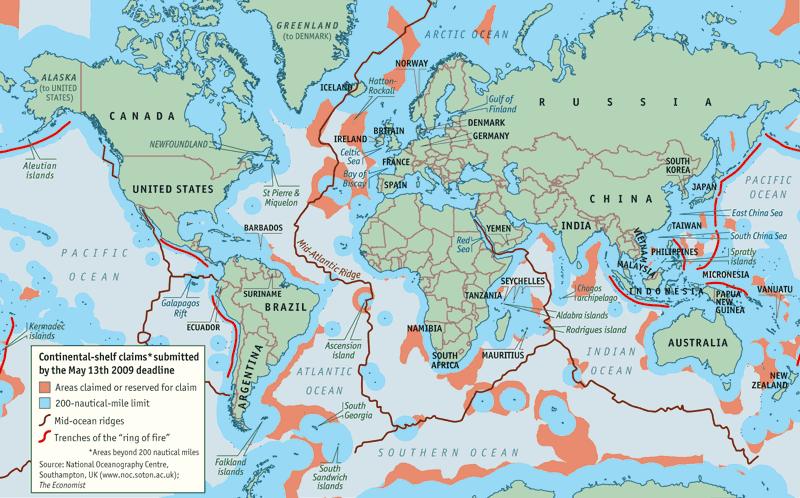

UNCLOS ratification enshrines the principles of freedom of navigation and access, thereby strengthening the U.S. position in the pacific region and the U.S. pivot to South East Asia (S.E.A.). Ratification supports future S.E.A. diplomatic developments through its focus on the region’s most prominent domain. Maritime territorial claims continue to inflict tension in S.E.A. and with UNCLOS as the primary legal guidance, the U.S. would be forced to stay on the diplomatic sidelines for a multilateral discussion without ratification. Yet, U.S. accession and ratification would result in isolation and a decline in future cooperation with those remaining maritime countries that have maintained disputes over UNCLOS and chose not to accept or ratify it, namely:

Cambodia, Colombia, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Ecuador, El Salvador, Eritrea, Iran, Israel, Libya, Peru, Syria, Timor-Leste, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Venezuela [1]

Despite the advantages Secretary Panetta and other U.S. advocates cite for the international maritime legal framework and global commons access rights (including the Arctic), the U.S. and other non-ratifying countries have long since acknowledged various negative aspects of the convention: increased non-local environmental policies, International Seabed Authority fees and taxes, international eminent domain grabs of intellectual property (to share new technology used in exploiting the economic opportunities of the expanded maritime domain), and the perception of a requirement to suspend all military-related actions while conducting innocent passage.

In order to fully address the impact of UNCLOS ratification to S.E.A. regional stability, countries such as the U.S. must weigh the finer points of the treaty and second-order effects its ratification might bring. As a new signatory, would U.S. diplomatic relations with Turkey and Israel now hinge on ignorance of Greece and Cyprus maritime boundary and Exclusive Economic Zone claims? As U.S. businesses continue to explore deep sea beds, would the U.S. concede to limited exploitation and research of (traditionally unquestioned) U.S. bodies of water by an international consensus? How would the U.S. discuss future fish stock trade with South American countries concerned with migratory fish locations beyond 200nm? Perhaps the U.S. pursuance of UNCLOS to support the pivot to the Pacific truly outweighs these other non-vital diplomatic considerations, but I can’t stop wondering if by doing so, the U.S. may cause yet another pivot among its allies.

You Sunk My…

I’m expecting a flood of Battleship-related posts in the near future with the U.S. opening this weekend. For instance, I’ve been promised a humorous take of this hard-hitting documentary over at USNI blog, so I’ll take a more straight-faced look at battleships.

I’m expecting a flood of Battleship-related posts in the near future with the U.S. opening this weekend. For instance, I’ve been promised a humorous take of this hard-hitting documentary over at USNI blog, so I’ll take a more straight-faced look at battleships.

As nukes are to the egos and deterrent calculus of nations today, so were battleships in the first half of the 20th Century. While the fact that today’s navies no longer possess battleships may be lost on this weekend’s moviegoers, what’s even more shocking is that after conducting extensive Wikipedia research, I uncovered no instances in which a battleship was sunk due to alien action.

This is an inexcusable error on the part of the filmmakers, but I thought our readers might nonetheless like to know the truth behind battleship sinkings. Below are the rough figures of the fates of post-Dreadnought battleships (excluding battlecruisers). Those not listed were scrapped, turned into a museum, taken to sea by Stephen Seagal, or commandeered by Cher (see photo above).

Doing some rough, back-of-the-envelope calculations, it looks like the number one cause of a sinking during a conflict (granted due primarily to the exceptional actions at Scapa Flow) was the hands of a ship’s own crew.

Sunk by Aircraft – 12 – 27%:

- – RN Conte di Cavour 1940

- – HMS Prince of Wales 1941

- – Marat 1941

- – USS Arizona 1941

- – USS West Virginia 1941 (Salvaged and returned to service)

- – USS California 1941 (Salvaged and returned to service)

- – USS Oklahoma 1941

- – USS Utah: 1941 (After conversion to an anti-aircraft training ship)

- – RN Roma 1943

- – SMS Tirpitz 1944

- – IJN Musashi 1944

- – IJN Yamato 1945

Scuttled to Prevent Enemy Use – 15 – 33%:

- – Imperatritsa Ekaterina Velikaya 1917

- – SMS Kaiser 1919

- – SMS Prinzregent Luitpold 1919

- – SMS Kaiserin 1919

- – SMS Friedrich der Grosse 1919

- – SMS König Albert 1919

- – SMS König 1919

- – SMS Großer Kurfürst 1919

- – SMS Kronprinz Wilhelm 1919

- – SMS Markgraf 1919

- – SMS Bayern 1919

- – SMS Bismarck 1941 (While under enemy fire – cause disputed)

- – Dunkerque 1942

- – Strasbourg 1942

- – Provence 1942

Surface Fire or Surface Torpedoes – 4 – 9%:

- – SMS Szent István 1918

- – Bretagne 1940

- – Fusō 1944

- – Yamashiro 1944

Torpedoed by Submarine – 2 – 4%:

– SMS Szent István 1918(h/t Chuck Hill)- – HMS Royal Oak 1939

- – HMS Barham 1941

Sunk as Breakwater – 2 – 4%:

- – HMS Centurion 1944

- – Courbet 1944

Sunk after Running Aground – 1 – 2%:

- – España 1923

Sunk by Frogmen – 1 – 2%:

- – Viribus Unitis 1918

Sunk by Claimed Sabotage – 2 – 4%:

- – RN Leonardo da Vinci 1916

- – Jaime I 1937

Sunk by Mines – 2 – 4%:

- – HMS Audacious 1914

- – España 1937

Sunk by Internal Explosion – 4 – 9%:

- – Imperatritsa Mariya 1916

- – HMS Vanguard 1917

- – Kawachi 1918

- – Mutsu 1943

Sunk by Aliens – 0 – 0%

Sunk During Peacetime

Scuttled at Sea:

- – USS Pennsylvania 1948

Sunk after Running Aground

- – France 1922

Sunk During Target Practice:

- – SMS Ostfriesland 1921

- – SMS Baden 1921

- – SMS Thüringen 1923

- – Aki 1924

- – Satsuma 1924

- – USS Washington 1924

- – HMS Monarch 1925

- – HMS Emperor of India 1931

Sunk During Underwater Nuclear Test

- – Nagato 1946

- – USS Arkansas 1946

Unknown Cause:

- – Novorossiysk 1955

Sunk due to Weather:

- – São Paulo 1951