Bloomberg News recently again raised the issue of LCS survivability. Survivability is justifiably important as it is one of the key characteristics that differentiates warships from commercial vessels. Yet there is something wrong with the debate about LCS survivability. In general, the arguments fall into one of three broad categories — patos, logos, or etos. These Greek words refer to our emotions, rational mind, and values. In discussing LCS survivability patos dominates over logos. When there is strong disagreement on a specific issue, it is sometimes useful to state the reasoning carried to its extreme in order to mark the boundaries of common sense. This lets us reconsider the validity of the initial assumptions and is a loose variation of the reductio ad absurdum method. We can say also that this is an emotional way of applying logic, justified in cases when pure logic is viewed does not satisfy emotional positions.

Consider whether the following statement is TRUE or FALSE:

“Level 3 ships are NOT survivable.”

It is always the possible to offer examples to support a TRUE assertion. An aircraft carrier will hardly survive the explosion of a nuclear torpedo under her keel. A more realistic and historical case is discussed in D. K. Brown’s “Nelson to Vanguard“, in which the battleship Prince of Wales – designed to withstand 1,000 lb. explosives – was sunk by aerial, light torpedoes with 330 lb. warheads. Nonetheless we consider ships designed according to the best contemporary practices as “survivable.” This simply demonstrates that survivability cannot be determined without defining the predicted level of threat. It is stated both in OPNAVINST 9070.1A and its predecessor. I find especially useful the threat- and conflict-level classification proposed by Rear Admiral Richard Hill (RN) in his paper Medium Power Strategy Revisited. Normal conditions with operations like constabulary work, disaster relief, and presence

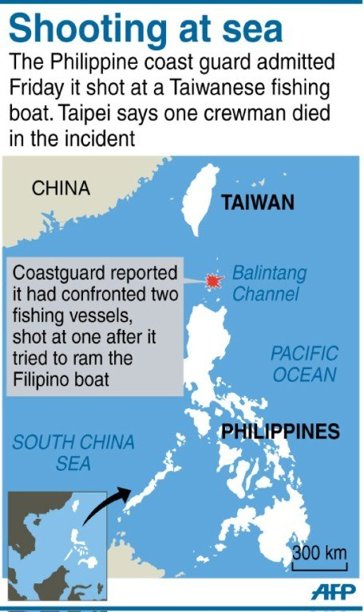

- Low intensity operations when “escort by surface combatants may be required.” “Cover by high-capability forces may be required, to deter or if necessary counter escalation.” These operations “are subject to the international law of self-defense, often include sporadic acts of violence by both sides, and have objectives that are predominantly political in nature”.

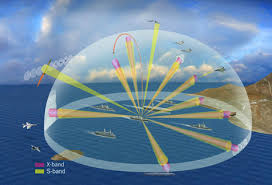

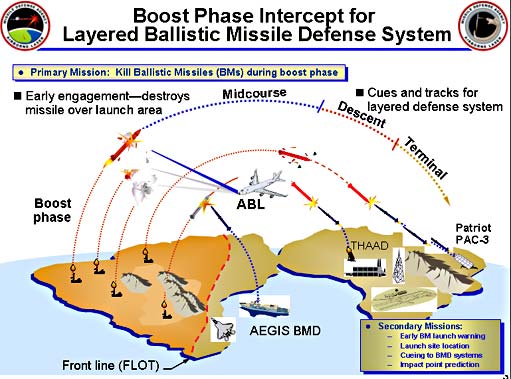

- Higher level operations with combat at the far end of the continuum. “The definition of ‘higher level’ includes ‘use of major weapon systems’, that is to say combat aircraft, major surface units, submarines, and extensive mining; missiles from air, surface and subsurface can be employed.”

Sail frigates and later cruisers were designed to be a scouts and to operate on commerce shipping lines, but were never intended to survive a clash with an enemy’s battle fleet. Royal Navy WWII destroyers were surely designed according to naval rules, but in the 1st year of the war they were exposed to a threat level unimaginable a few years earlier and suffered a loss of 124 ships sunk or damaged out of the 136 in service at the outbreak of war.

I also offer this statement for consideration:

“It is possible to design and construct 300-ton Fast Attack Craft with Level 3 survivability.”

Theoretically the statement is TRUE, but it is enough to recall the transformation of HMMWVs into MRAPs, which could be described as improving Level 1 survivability to Level 2, to understand the technical and economic limitations to such an endeavor. There was an interesting paper presented last year to the Royal Institution of Naval Architects – Balancing Survivability, Operability and Cost for a Corvette Design. It offers interesting insights into unavoidable compromises, and a not-so-surprising conclusion that the best way to increase survivability is to increase the length of the ship. From this point of view both LCS are of good design, but LCS also falls into a design trap. Longer and bigger ships lead to criticism of being underarmed. Up-arming the ship would lead to higher costs and reduced affordability. This in turn means a smaller fleet and an increased gap between force-structure requirements and reality. Such a gap leads to questions of whether it can be filled by smaller ships. But these are in turn “not survivable”. Vicious circle closed.

Ship survivability is a complex issue, including such things as the probability of being hit, tolerance to damage, and recoverability. I cannot judge whether LCS is survivable or not. The better question to ask is if it is survivable enough – taking into account its size, mission, and the projected threat level in its intended operating environment. Such a discussion is vital to every class of ships and calls for carefully balanced patos and logos.

Przemek Krajewski alias Viribus Unitis is a blogger In Poland. His area of interest is broad context of purpose and structure of Navy and promoting discussions on these subjects In his country