International Maritime Satire Week Warning: The following is a piece of fiction intended to elicit insight through the use of satire and written by those who do not make a living being funny – so it’s not serious and very well might not be funny. See the rest of our IntMarSatWeek offerings here.

It’s a classic from your childhood, but in the cut-throat board game business nothing is sacred.

In a surprise move the board game manufacturer Hasbro announced a series of changes to their stalwart wargame classic, “Battleship,” that would bring it into the 21st century. Their name of choice: “LCS,” referring to the Navy’s recently introduced Littoral Combat Ship (LCS).

“We thought it was time to bring ‘Battleship’ in line with the modern U.S. Navy,” said Martin Sawyer, the spokesman for Hasbro game, at a press conference on Friday afternoon. “When you think of the missions of a modern navy, you immediately think of the LCS.”

Hasbro officials believe that, while the image of a massive capital ship with unquestioned firepower was enough to carry the franchise over the past five decades, the name “Battleship” no longer resonates with their young target demographics.

“The age of the battleship has clearly passed. Heck, it was gone by the time we made the game. It’s time to make this a modern game.” Off the record, sources say the real reason for the change may be that the rare earth metals used to make the aircraft carrier pieces became exhorbiantly expensive, scuttling the move to rebrand the game “Carrier.” Officials also say the fact that ‘LCS’ contains 3 syllables played a role – enabling players to bemoan in the traditional “you sunk my….” phrasing the sinking of their vessels, over and over again.

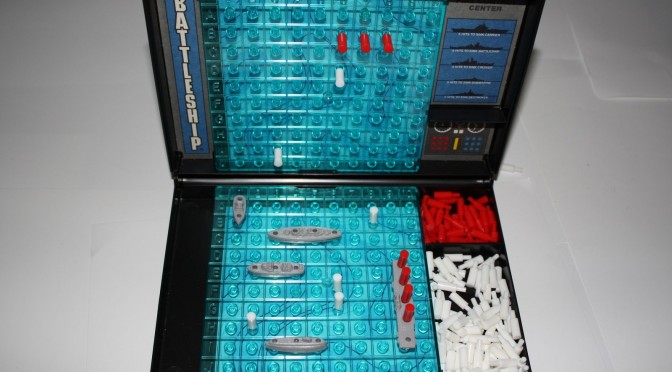

Battleship, which first started as a pen-and-paper game in the 1930s, has been a Hasbro mainstay since it was first released in its present form in 1967. In the game, two would-be fleet commanders square off in a battle of wits, vigor, and dumb luck by blindly firings at points on a grid to damage their opponent’s navy. Ships “sink” when they receive a requisite number of hits. Smaller ships, like the destroyer, take up fewer spaces on the grid and are thus harder to hit. This leads to real-life situations where the destroyer is more valuable than other, larger ships such as the cruiser, submarine, and aircraft carrier. “LCS” will build off this trend by replacing the ships in each navy exclusively with LCS destroyers.

The U.S. Navy was quick to praise the changes. “The LCS is a testament to the future of the low-observable Navy,” said Navy spokesman Lt. Cmdr. Michael Fabian. “It stands to reason that a game like ‘Battleship,’ where navies wildly shoot at empty water in an attempt to hit something, perfectly reflects the capacity of the LCS in the naval domains of the future.”

After battling aliens, pirates, and G.I.Joe, Battleship is moving on

Others, though, are not convinced. Some members of the surface warfare community that were allowed to playtest the new version have instituted the “Fire Scout” rule, referring to the shipboard UAV, which allows a player to look at the opponents board before declaring their shot. “Even if LCS is low-observable we still have eyes and flying robot cameras with persistent-loiter capability,” said one surly surface warfare officer.

“Seriously,” he said, “we can still see them with our freaking eyes.”

Members of the Air Force also added their own ruleset “Rods from God.” In the Rod God Mod, players are allowed to look at their opponent’s board and then immediately destroy a ship of their choice with tungsten rods dropped from satellites. “Take that, naval power!” said an Air Force playtester, right before the same rods destroyed his immobile, land-based runways in the modified game.

In conjunction with the rebranding, Universal Pictures announced that the blockbuster movie Battleship would be given a gritty reboot in line with the boardgame. Gone is the emphasis of capital ship warfare against aliens; instead, the movie will feature even greater suspension-of-disbelief in the dazzling capabilities of the LCS on the silver screen.

“Audiences will marvel at the LCS as it uses stealth technology to sneak up on pirate skiffs that lack radar and then do nothing further from lack of evidence that they are pirates!” said Universal sales representative Lester McPeak. “Think Captain Phillips but with less shooting and more bureaucracy.”

Added McPeak: “If Jack and the Beanstalk and Hansel and Gretel can get gritty reboots, we can totally do that for Battleship too. As long as we keep the same actors and writers, we should be just fine.”

Matthew Merighi is an employee of the United State Air Force, but we tolerate him anyway. His views do not reflect those of the United States Government but he hopes they are appreciated by other snarky Pentagon millennials.