Introduction

American strategic thought should center on war with China, a near-peer competitor who aims to expel U.S. military power from the Western Pacific in order to achieve regional hegemony.[1] U.S. leaders need strategic options on how best to engage, deter and ultimately defeat China. The geography of the region demands a maritime focus, and as policy makers have decided to “pivot” to Asia, it is incumbent on them to decide how best to posture American power. Maritime power will be the deciding factor in this conflict.

This is not to say that a conflict with China is inevitable or desired. Yet the responsibility of policy makers, military planners and national security experts is to consider and plan accordingly for conflict. Not assuming that war will come will mean the fight will be longer, harder and more costly – and more in doubt.

In the last half of the 20th Century, American maritime power was the centerpiece in a policy of containment against Communism. The collapse of the Soviet Union left the U.S. Navy as the uncontested power on the world’s oceans. [2] Power projection and unrestricted use of the sea lanes enabled the U.S. to fight two sustained land wars for more than ten years. Our pivot toward Asia, demands we build our future maritime power capabilities and platforms around our strategy.

War with China must be an immediate concern. The stage is already set for America to be drawn into conflict now, while she is underprepared. Consider the following scenario:

Late 2014

The conclusion of the 18th Chinese Party Congress in November 2012 did not soothe growing ethnic and economic tensions in China.[3] A stalled world economic recovery reduced demand for Chinese-made goods, creating an unemployment crisis in a country where employment is “guaranteed.” Ethnic tensions spilled over in many western and rural provinces and the state security and People’s Liberation Army (PLA) wavered between accommodating and cracking down. Sensing the Communist Party was losing its “Mandate from Heaven”,[4] it initiated a series of territorial disputes with Asian neighbors in the hopes of spurring nationalism. In late 2014, PRC law enforcement vessels of the China Marine Surveillance (CMS) agency placed water barriers around Scarborough Reef, a disputed shoal claimed by the Philippines and the PRC. An amphibious craft over the horizon with prefabricated construction materials set up a small “Maritime Surveillance Outpost” on pylons manned by marines and “fishery law enforcement” officers. Lacking a meaningful navy, and the stomach to fight, the Philippine government filed protests at the United Nations (UN) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). The U.S. ignored quiet feelers put out by the Philippine government about military support for a response, and the PRC noted the lack of a forceful U.S. reaction to the aid their treaty ally.

After a brief “high” from their triumph, the economic situation continued to worsen through 2015. The Communist leadership looked closer to home for another diversion. In the East China Sea, just north of Taiwan, the PRC and Japan were locked in a territorial dispute over the Japanese-administered Senkaku Islands. Noting the lack of support Washington gave the Philippines, China waited until the carrier USS George Washington was back in its home port of Yokosuka, Japan undergoing regular maintenance. With the absence of a transiting carrier strike group, hundreds of fishing boats loaded with PLA Navy [PLA(N)] marines come ashore and hastily build a “Maritime Surveillance Outpost” on two of the larger islands. The few Japanese Coast Guard ships could not prevent the landing and soon the islands were occupied with marines and light artillery. Tokyo showed more resolve, and vowed to retake the “home territory.” To the surprise of the American leadership, Japan invoked the mutual defense treaty with the United States, and America’s political leadership faced its worst nightmare: a conflict with China.[5]

Strategy and Maritime Power

We begin by making a series of assumptions. First, the policy of the United States is to remain the preeminent world power. Relative decline need not be indicative of retreat from global leadership; America will continue to oppose usurpation by one or more powers whose interests do not largely coincide with our own. A multi-polar world is more dangerous, not less.

Second, America will seek to maintain a qualitative military edge over peer competitors, enabling it to be capable of protecting national security interests worldwide. Finally, American policy will seek to ensure continued global economic integration and will fund a military large and capable enough to secure the global commons.

In order to meet these assumptions, U.S. strategy must navigate a series of challenges in North Africa, the Middle East and Iran, North Korea, Russia and China. All of these are potential flashpoints of military conflict that could escalate, but only one – China – has the ability to fundamentally alter America’s position in the world and take her place as the preeminent power. The ability of America to respond hinges on maritime power.

The nature of American maritime power has evolved over time, as outlined in 1954 by Samuel Huntington. During the Continental Phase, from the founding to 1890, the Navy played a subordinate role, primarily responsible for coastal defense, protecting American commerce and during the Mexican-American and Civil Wars, performing blockading functions and amphibious operations. Beginning in 1890 through the end of World War II, the Oceanic Phase, the United States began to project its power and interests overseas. Maritime policy and thinking was largely influenced by Alfred Thayer Mahan. He argued that the “true mission of the navy was acquiring command of the sea through the destruction of the enemy fleet.” To secure command of the sea, the nation required a stronger battle fleet. This doctrine was largely accepted by the Great Powers, including Japan.[6]

The third phase, the Transoceanic Phase, has seen maritime power orient away from the open ocean and toward the littorals. Even Admiral Nimitz would note that the reduction of enemy targets on land “is the basic objective of warfare,” not the destruction of the enemy fleet. The purpose of maritime power since the end of World War II is to “utilize command of the sea to achieve supremacy on the land.” In a sense, Mahan has been replaced by Sir Julian Corbett.[7]

Maritime power has distinct advantages for policy makers. It is the most politically viable option to posture military forces and respond to challenges without the need for a large land presence. Foreign powers, coalition partners and allies(and the local populations) prefer regular port visits, exercises and training engagements than the permanent stationing of troops. The American public has also cooled to the idea of large battalions stationed overseas. As the public has also grown more casualty-averse, policy makers need more time to prepare the public for the eventual introduction of land forces and the potentially large number of casualties. The nature of a maritime conflict – slow to escalate – provides the political leadership the most critical of elements in any conflict: time.

Maritime power should not be confused as “Navy-only,” or even “Navy-Air Force-only.” Land forces play a critical role. As Rear Admiral J.C. Wylie[8] noted, “The ultimate determinant in war is the man on the scene with the gun…This is the soldier.” Land operations are critical in a conflict where the littorals play a central role. The hypothetical scenario above is an example.

Space and cyberspace are newer elements of maritime power. Modern navigation, intelligence gathering and communication, including the Internet, rely on satellite technology and architecture. In the mid to late 1990s, the U.S. military began reconfiguring itself for network-centric operations, linking combat platforms and intelligence surveillance reconnaissance (ISR) assets. At sea, this is critical to Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA). The backbone of a networked military is the satellite and cyberspace architecture and is vital to joint operations.

The Dual Nature of War

Before considering conflict with China, we have to consider the nature of war itself. War is dichotomous, being fought principally on land, or with both land and maritime elements.[9] John Arquilla[10] identified that in land wars, skill was the primary factor which determined victory or defeat, while in wars involving land-sea powers, maritime power was the determining factor.

Land powers which initiate wars with land-sea powers tend to lose, often because they inflate their own naval capabilities and lack the requisite experience in naval operations. 16th Century France and 19th-20th Century Germany are two examples. Both were continental powers that began a program of naval expansion with the intent to challenge the British at sea and reach a position of dominance. Both entered conflicts with Britain, only to find that their newly expanded navies did not perform as expected. Their naval bureaucracies retreated from the offensive doctrines in order to protect their new – and very expensive – fleets. Once hostilities commenced, they turned from offensive operations to a guerre de course (commerce raiding), a defensive naval strategy. However, their peacetime advocacy of an offensive naval doctrine made conflict more likely, not less.[11]

About the Author

LT Robert “Jake” Bebber USN is an information warfare officer assigned to the staff of the United States Cyber Command. He holds a Ph.D. in Public Policy from the University of Central Florida. The views expressed here do not represent those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Navy or the U.S. Cyber Command. He welcomes your comments at [email protected].

Sources

[1] For a more thorough view, see John J. Mearsheimer’s article “Can China Rise Peacefully?” at The National Interest, April 8, 2014, available at: http://nationalinterest.org/commentary/can-china-rise-peacefully-10204.

[2] Peter M. Swartz, Center for Naval Analysis, personal communication, November 8, 2012.

[3] For example, see “China’s Achilles Heel” in The Economist, April 21, 2012: http://www.economist.com/node/21553056 ; “Unrest in China – A dangerous year” also in The Economist, January 28, 2012: http://www.economist.com/node/21543477. Also, see “Uighurs and China’s Xinjiang Region” in Council on Foreign Relations, May 29, 2012: http://www.cfr.org/china/uighurs-chinas-xinjiang-region/p16870.

[4] For more on the concept of the “mandate of heaven,” see Perry, E. J. “Challenging the mandate of heaven: popular protests in modern China.” Critical Asian Studies 33, no. 2 (2001): 163-180.

[5] See “Treaty with Japan covers islets in China spat: U.S. official” (Reuters) September 20, 2012, available at http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/09/20/us-china-japan-usa-idUSBRE88J1HJ20120920

[6] Huntington, Samuel P. “National Policy and the Transoceanic Navy. Proceedings 80 no. 5 (1954).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Wylie, J.C. Military Strategy: A General Theory of Power Control. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1967. Pg. 72.

[9] Air power is a major component of both land and land-sea war and hence, is not treated separately.

[10] Arquilla, John. Dubious Battles: Agression, Defeat and the International System. Washington, DC: Crane Russak, 1992. Pg. 131.

[11] Ibid. pp. 99-129

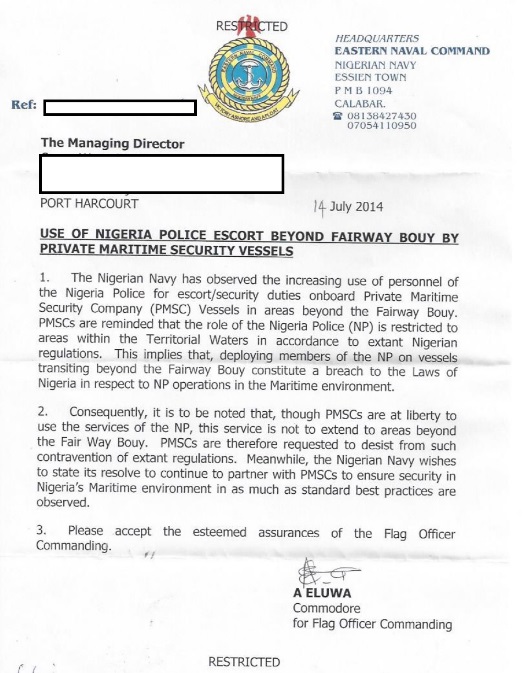

![[Photo: “Acknowledgement of receipt” provided by a security provider to a client as “evidence” of approval to embark naval personnel.]](https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/security-receipt.jpg)

![[Photo: Damage to the bridge of SP BRUSSELS from the firefight on the bridge. (Source: withheld)]](https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Brussels-damage.jpg)

![[Photo: The SEA STERLING on Lagos roads in April 2014. (Dirk Steffen)]](https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Sea-Sterline.jpg)

![[Photo: NNS IKOT-ABASI, pictured here on Lagos roads in April 2014, responded to the distress call made by the SP BRUSSELS. (Dirk Steffen)]](https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/IKOT-ABASI.jpg)