This piece by W. Alejandro Sanchez is part of our Future Military Fiction Week for the New Year. The week topic was chosen as a prize by one of our Kickstarter supporters.

Waking Up

“Jesus, Maria y Jose, this heat is impossible,” I said at around 5am. The sun had yet show up in the dessert but it was hot enough. Well maybe not too hot, it was an acceptable 20 degrees Celsius (68 Fahrenheit to the uneducated) but you know, I was born in the Andes so I am not used to the heat. “Why couldn’t we start this war in the winter? Everyone would be miserable except me at least,” I said to whatever ghost still inhabited this abandoned room.

Then again, I was still mostly in my uniform: the standard desert-pattern cargo pants, my belt, socks. I was even wearing still those damn boots that, while resilient, made my feet hurt. It was common sense to sleep all dressed up in the battlefield, with your rifle next to you, in order to be ready if (or more like when) the enemy showed up.

With that said, I did make the executive decision to take off my jacket and t-shirt. I have never been able to sleep with a t-shirt on and it was the first time in like three weeks that we had been able to sleep with an actual roof on our heads.

A nice roof, mind you. “I wonder whose house this had been,” I had said, again out loud, when I camped here last night. Then again, I rather not know. I made sure I did not look at the pictures of this nice little two-story home in this mid-sized town that my unit had been sweeping the day before.

From what I could tell from the corner of my eye when I looked at the pictures as I walked by, this had been the home of a 7-person family. “The spoils of war,” I thought as I peeked through the window, pulling the curtain aside just a bit to see that, indeed, the only source of light from anywhere in the horizon came from the moon.

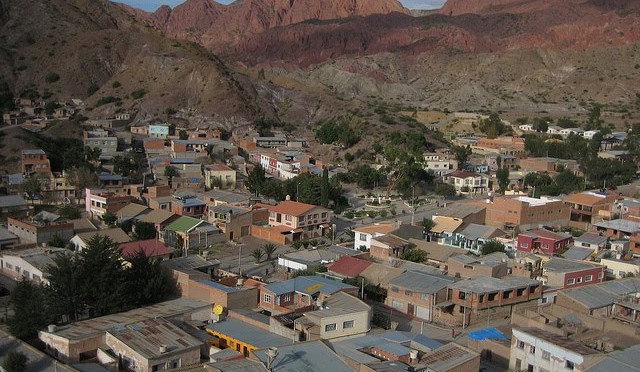

Prior to the war this town had been the home of some five thousand people. Now it was the home of at least five thousand stray dogs, cats and rats.

I bent over, which made my poor back crack. Carajo! I cursed and then grabbed my FN Herstal. I liked this rifle, my government had bought a few thousand of them from the Belgians a few years ago and it had paid off. It was a good weapon, light but the bullets packed a good punch.

It had taken me longer than I cared to admit to get used to it instead of the old-school FAL rifle that the army had used for generations. My father, uncle and other relatives had trained with it when they were soldiers and still joked about how the damn thing was taller than some recruits.

But the change to a younger, sleeker weapon had been worth it. This efficient little rifle was the cornerstone of why the army had been so successful in the first months of the war. Well that, some good strategy and a successful surprise attack that had taken the enemy, our perpetual southern neighbors, by surprise.

I drank a big gulp of water from my canteen and briefly considered following it with a gulp of pisco from my flask, nicely hidden in one of the inside pockets of my jacket, but decided against it. It wasn’t even 6am and I figured I should be fully sober for a couple of hours more.

I stood on the edge of the door for a moment, letting my eyes adjust to the darkness and then began walking downstairs. I could easily distinguish the shapes that constituted the other soldiers of my unit, part of the 13th Counterinsurgency Regiment. We were a ragtag bunch, remnants from the original unit from when the war began plus new recruits. Not to mention the really green recruits and paramilitaries that had joined as time passed. In my early 30s, I was already regarded as a veteran simply because of having survived longer than most others around here.

I walked down the stairs, and only then proceeded to put on my t-shirt, Kevlar vest and jacket, enjoying the last moments of freedom from all that extra weight. Sergeant Juan Jose Gambini, mi Segundo, walked up to me, already in full uniform (did he sleep in that thing?). He gave me a sharp salute, with a broad grin. “Nothing to report, señor. The Western scouts came back a while ago, no sightings of rotos.”

Everyone has a nickname for the “enemy,” the Allies called the Germans the “gerries” and we called ours either “los rotos” or “los vecinos”.

“Vanessa must have been upset that she did not get to unleash Marta on anyone,” I said with a little mischievous smile.

“Correct señor, she was a bit grumpy, but you know her, she’s quite the optimist.”

At this point in the war, neither side could afford to stick to that old, silly, machista culture that Latin Americans are known for. Even though we were winning, we could not afford to keep our female soldiers serving “support” roles. We needed everyone who wanted to fight and could fight in the front lines.

Unsurprisingly there had been the standard sexist comments when female soldiers began fighting in the front lines. “Can they shoot?”; “What if they get hurt?”; “Can they carry all that equipment?”; and the ever-present “No necesitamos mujeres.” I am sad to say that not all in my unit had been as welcoming to female fighters as I had wished.

Nevertheless, the addition of a female component only increased our efficiency. Vanessa is a person mind you, but Marta is the name of M82A1 rifle that she used with deadly efficacy. That is not the rifle she was originally given at the start of the war, she had lost that one during the Battle of Tarapaca in an amusing hand-to-hand combat. She found Marta a few days ago and her new rifle already had five notches.

If nothing else, this war had proven that both genders could be just as deadly and effective in combat as the other.

Mi segundo left to wake up the rest of the troops as I walked throughout the rest of the house. I got on knees when I got to the kitchen and crawled my way out into the dark backyard and from there across to the neighboring also two-story house.

I believed Gambini when he told me that there were no enemy combatants in sight, but I was just as sure that the enemy probably had their own version of our 5 foot and 5 inches-Vanessa: a sniper in some roof just waiting as patiently as a hungry serpent for some silly officer to stick his head up just a centimeter too high over a fence.

Eventually I crawled the 30 meters, more or less, of backyard to the next house and entered through the kitchen. I could smell some rotting food on the table and I tried not to throw up. The smell of rotting food always got to me.

Lying on the ground by a hole in the wall was Corporal Humberto, holding, caressing one would say, his trustworthy ZH-05 grenade launcher. The launcher was Chinese and it had a wicked kick to it. It was also deadly effective.

Humberto held it securely but also with pride while he admired his work: some three hundred feet away lay the remains of a Leopard tank. Their enemy’s bought a couple hundred of those tanks years ago. This particular Goliath had been deployed here with around a dozen supporting troops to stop our forces from taking over the town.

It had been a difficult fight the night before but my unit had prevailed and we had Humberto, his grenade launcher, and two fallen comrades to thank for that. Vanessa had scratched Marta twice that night. The two had taken the tank’s gunner as well as a lieutenant who was hiding behind what looked like a Mercedes (that’s as far as my knowledge of cars goes). If the troops had any problems with having any female in our unit, these reservations died that night.

Funny how sexism and racism can evaporate in extreme circumstances if you show how much of a badass you are.

I spoke with Humberto for a few moments. Unsurprisingly, nothing had happened for the past few hours, but we were certain that the enemy had noticed that one of their patrols, including one of those impressive and expensive tanks, were missing.

I sat next to my comrade, whispering a carajo as my back cracked again. I saw across the room and saw two of our paramilitaries sitting there. Their uniforms were… well they were not uniforms. More like a combination of military pants and black sweaters. “Rimaykullayki ¿Allillanchu?,” one of them said at me, with a friendly wave. Humberto frowned as there was no “sir” in their greeting, but I did not care. We were not a priority unit so we got paramilitaries to refill our ranks. They cared little for military discipline and hierarchy… and they spoke Quechua and very little Spanish, but they were good fighters. And I was going to need more good fighters.

Finally I saw our pirate’s booty. Across the floor was a little amalgamation of weapons we had collected from the deceased. Our prized trophy was the Rheinmetall MG 3 machine gun that we had managed to save from that enemy tank before the fire took it.

At this point I had plenty of weapons at my disposal, enough to take a small regiment, but alas I did not have enough fingers to pull all the triggers (I made a mental note of asking the captain for more paramilitaries).

Humberto handed me some grapes that we had picked up from the trees around the house and I tried to not wolf them down in one handful. El desayuno.

I took this moment to pick out a couple of papers from my backpack. They were some commentaries I had printed weeks ago from some American think tanks about our little conflict. The gringo scholars were trying to figure out why this war had come to be and who was behind it.

I could not help grunting a bit in disgust. Yes, my country had bought tanks and helicopters from the Soviet Union and, yes, we had bought new Russian tanks in the past years. But really, does this made my government, and the army I was part of, Moscow’s client state? Was it so unconceivable to believe that countries could still go to war with each other not because the powers-that-be decided it, but because of our own national interests… or because we just did not have anything better to do on a Tuesday?

We already knew the reasons for the war, I thought as I drank more water, wishing it was alcohol, after I had finished with the grapes. El Presidente had gone on TV, radio, print media and social media (he loved to tweet) to make his predictably nationalistic speeches about us fighting the good fight. “Los rotos no son de confiar,” he had boldly proclaimed during a speech in one of our big southern cities. I guess he picked the place so the city’s volcano (an active one) would appear in the shots, making him appear even more defiant. “Si no atacamos, sera como en la guerra del siglo 19,” He also said, which was true. We had been attacked first in the 19th century and we were ever-weary of them attacking us first again.

But it quickly became clear that we had started this war for resources: lithium and copper. Bolivia, our other neighbors, were known as the “Saudi Arabia of Lithium,” but the “rotos” had recently located some big veins of lithium, which, combined with their already vast copper industry (the biggest one in the world), would make it a regional economic powerhouse.

And we could not let that happen.

Lucky for us the enemy was in disarray, university students and some indigenous groups were protesting again. Hence, the government had been more focused on internal security rather than checking on what neighboring militaries were up to. I know, gulping more water (que sed!), sneak attacks are not particularly brave things to do, but we were going for victory here, not heroism.

Suddenly my earpiece came to life. “We got company señor, a column of five-six humvees are approaching. They look gringo made, there are a couple of trucks behind,” said my second in command. This was obviously the enemy we were expecting as my army did not have any humvees in our arsenal.

For the fifth time in 25 minutes I considered taking quick gulp of the pisco for my nerves but decided against it, once again. I turned around to face Humberto and the paramilitaries. I felt bad that I have yet to learn their names – not that it mattered, everyone looks the same with a black ski mask on anyways.

Out of habit, I checked that my Herstal rifle was still hanging from my shoulder and, also out of habit and because I did not want to make an ugly corpse, I checked myself on a broken mirror that I found on the ground. Sadly, I still had greasy bed hair. I unceremoniously dropped the mirror, making it break a couple of more times, and nodded at my soldiers, “vamos, the barbarians are at the gates.”

Humberto smiled and stood up, carrying his trusty grenade launcher. He and the others grabbed the machine gun and some of the rifles that littered the room. I cursed at myself, “I should have spread this around to everyone else last night.” I helped by grabbing a couple of Makarov pistols and some ammo for the machine gun.

“Russian pistols, Chinese grenade launchers, German tanks, American jeeps… I’m fairly sure our uniforms are from India…there is not one ‘made in your homeland’ product here is there?” Humberto said to no one in particular as he briskly walked to the kitchen door. No one shot him so I figured that, indeed, there was no enemy sniper out there.

The two other Quechua-speaking paramilitaries followed him, not saying a word. I stood by the door for a moment, trying to see anything as the day dawned. I saw Vanessa and Marta leave the house rapidly making their way across the street. There was a 4 story-building not far which I guess would be her new location to greet our incoming guests.

I was in the process of multitasking again, walking and sneezing (guess sleeping shirtless was not such a good idea in spite of the heat), when a small ghost tackled me to the ground.

Carajo, I guess there was a sniper out there after all.

The year is 2021.

This is the story of the second War of the Pacific.

This is not a story about heroes and villains, but a story about an unknown war fought by unknown soldiers.

The author would like to thank M.M. and S.D. for their invaluable editorial suggestions.

All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. This story is a complete work of fiction. In no way does it represent the points of view of any of the organizations that this author is affiliated with.

In one of the last Asia Pacific podcasts for 2014, Sea Control Asia Pacific turns to the Middle East: the first 100 days of airstrikes against ISIL, to be specific. Natalie Sambhi interviews the

In one of the last Asia Pacific podcasts for 2014, Sea Control Asia Pacific turns to the Middle East: the first 100 days of airstrikes against ISIL, to be specific. Natalie Sambhi interviews the