THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PRINTED ON APR 4, 2013 AND IS BEING RE-PRINTED FOR “CHALLENGES OF INTELLIGENCE COLLECTION WEEK.”

One of the most vexing questions in international law is determining under what circumstances a state may lawfully use military force against another state or non-state actor. The U.N. Charter takes a very conservative approach: use of force, according to Article 51, is authorized “if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security.”1 The international community has long since abandoned the notion that a state must wait until it is actually under attack before it can employ military force. Instead, the concept of “imminence” has been read into Article 51. Daniel Webster famously articulated this rule after the so-called Caroline case: preemptive force can be used only if there is “a necessity of self-defence, instant, overwhelming, leaving no choice of means, and no moment of deliberation.”2 But even this more deferential rule has proven unworkable in the age of modern warfare. Modern military technology and techniques allow aggressors to launch devastating attacks without significant notice. Additionally, terrorist groups have become increasingly sophisticated in both their tactics and capability to evade detection. To combat these threats, states often gather intelligence that must be acted on in a matter of hours, and special forces are prepared to respond to threats on extremely short notice. For example, President Obama ordered U.S. Navy SEALS to attack a compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan that was believed to be housing Al Qaida leader Osama Bin Laden. Although the operation turned out to be a major success, Obama later explained that his advisors were only 55% confident that Bin Laden was in the compound.3 Of course, there was no suggestion that Bin Laden was planning an imminent attack on the United States, or even that he would soon relocate to a new hideout. The time-sensitive nature of the intelligence and the enormous stakes, however, justified the use of military force without any delay to collect more detailed intelligence or seek the aid of the Pakistani government. The Abbottabad raid is an example of how the traditional notion of imminence must be adapted to meet the needs of the Global War on Terror. This post seeks to explain why such a shift is needed and suggests a framework for evaluating the use of military force when a threat is not imminent in the traditional sense.

One of the most vexing questions in international law is determining under what circumstances a state may lawfully use military force against another state or non-state actor. The U.N. Charter takes a very conservative approach: use of force, according to Article 51, is authorized “if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security.”1 The international community has long since abandoned the notion that a state must wait until it is actually under attack before it can employ military force. Instead, the concept of “imminence” has been read into Article 51. Daniel Webster famously articulated this rule after the so-called Caroline case: preemptive force can be used only if there is “a necessity of self-defence, instant, overwhelming, leaving no choice of means, and no moment of deliberation.”2 But even this more deferential rule has proven unworkable in the age of modern warfare. Modern military technology and techniques allow aggressors to launch devastating attacks without significant notice. Additionally, terrorist groups have become increasingly sophisticated in both their tactics and capability to evade detection. To combat these threats, states often gather intelligence that must be acted on in a matter of hours, and special forces are prepared to respond to threats on extremely short notice. For example, President Obama ordered U.S. Navy SEALS to attack a compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan that was believed to be housing Al Qaida leader Osama Bin Laden. Although the operation turned out to be a major success, Obama later explained that his advisors were only 55% confident that Bin Laden was in the compound.3 Of course, there was no suggestion that Bin Laden was planning an imminent attack on the United States, or even that he would soon relocate to a new hideout. The time-sensitive nature of the intelligence and the enormous stakes, however, justified the use of military force without any delay to collect more detailed intelligence or seek the aid of the Pakistani government. The Abbottabad raid is an example of how the traditional notion of imminence must be adapted to meet the needs of the Global War on Terror. This post seeks to explain why such a shift is needed and suggests a framework for evaluating the use of military force when a threat is not imminent in the traditional sense.

Changing Nature of Threats

The notion of imminence is an intuitive concept for most people. The requirement is familiar from domestic criminal law, which allows a person to use deadly force in self-defense if he believes such force is “immediately necessary for the purpose of protecting himself against the use of unlawful force….”4 The imminence requirement is also consistent with the predominant view of international relations, enshrined in Article 2(4) of the U.N. Charter, that states are to refrain from using force against another state unless authorized by international law.5 This rule, although a good starting point, is strained by the realities of the current international system.

The imminence requirement developed in a time when military conflict occurred almost exclusively between sovereign nations. It was relatively simple to detect a neighbor amassing conventional forces along your border or positioning naval forces off your shore. It also developed in a time when wars were fought by conventional means: by soldiers on battlefields. The need for imminence applied only in deciding to initiate military force. Once two states were at war, there was generally no requirement of imminence before engaging enemy forces.6 The rise of non-state terrorist groups has altered this dynamic in two important ways. First, terrorist groups have developed tactics that are difficult to anticipate. If states wait until a terrorist attack is imminent, they may be unable to prevent a catastrophe and may have difficulty attributing blame after the fact. Second, because terrorist groups are non-state actors, it is often unclear who is a combatant that may be targeted and who is merely a bystander or sympathizer.

Despite the difficulties of applying the imminence requirement in a post 9/11 world, the Obama administration has continued to acknowledge a need for imminence when using military force against members of Al Qaida and other terrorist groups. In a Department of Justice white paper the Obama administration concluded that deadly force could be used against an American citizen abroad if that citizen “poses an imminent threat of violent attack against the United States” and capture is infeasible.7 In a 2011 address, John Brennan, who at the time was President Obama’s Homeland Security Advisor, remarked that imminence would continue to play an important role in constraining America’s use of military force to conform to international law. Importantly, he qualified his support by stating: “a more flexible understanding of ‘imminence’ may be appropriate when dealing with terrorist groups, in part because threats posed by non-state actors do not present themselves in the ways that evidenced imminence in more traditional conflicts.”8 Articulating this new approach to imminence will be an important foreign policy challenge as the U.S. continues to prosecute the war or terror. The U.S. must develop a conception of imminence that both maintains the legitimacy of our military actions under international law and allows us to act preemptively against terrorist attacks.

Additional Factors to Consider

Altering the criteria for the lawful use of military force is a delicate task. Taken to an extreme, a more flexible rule could stipulate that force is appropriate whenever the potential benefits of a military operation outweigh the potential costs.9 This is the decision-making process envisioned by proponents of International Realism. States, as rational actors, would take any action in which the expected benefit exceeded the expected cost. Because, in the realists’ view, the international system is anarchic, there are no extra-national rules that govern when use of force is appropriate. The views of realists, however, have been largely rejected by the United States. If force is used in an unbounded manner, we risk losing legitimacy with the international community. Instead, the new paradigm must incorporate additional factors while still limiting the use of force by imposing legal constraints.

In a 2012 speech Attorney General Eric Holder suggested a new framework for determining which threats are imminent. When considering use of force against a terrorist target, the United States would consider the window of opportunity to act, the possible harm that missing the window would cause to civilians, and the likelihood of heading off future disastrous attacks against the United States.10 This framework is a step in the right direction. The primary shortcoming of the traditional imminence doctrine is that it fails to adequately consider the potential cost of failing to act. The magnitude of a potential threat is an important consideration in deciding when preemption is justified. It is appropriate to preempt a nascent nuclear attack at a much earlier stage than would be appropriate for an attack using conventional weapon. Considering the window of opportunity allows decision makers to weigh the risks of inaction. A related concept is the so-called “zone of immunity.” This term was coined by Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak, and refers to a situation in which failure to take prompt military action will result in the enemy being immune from future attack.11 For example, Barak argued that after a certain point, Iran’s nuclear program would be sufficiently safeguarded that no aerial strike could disable it. When there is potential for a zone of immunity, the relevant question should not be when an attack is imminent, but when immunity is imminent. This flexibility does not mean that force can be used without limits. As Attorney General Holder explained, the use of force is always constrained by four fundamental principles: necessity, distinction, proportionality, and humanity.12 With these limitations intact, it is appropriate to consider the window of opportunity, zone of immunity, and the magnitude of harm that a successful terrorist attack would occasion.

Using Technology to Develop New Standards

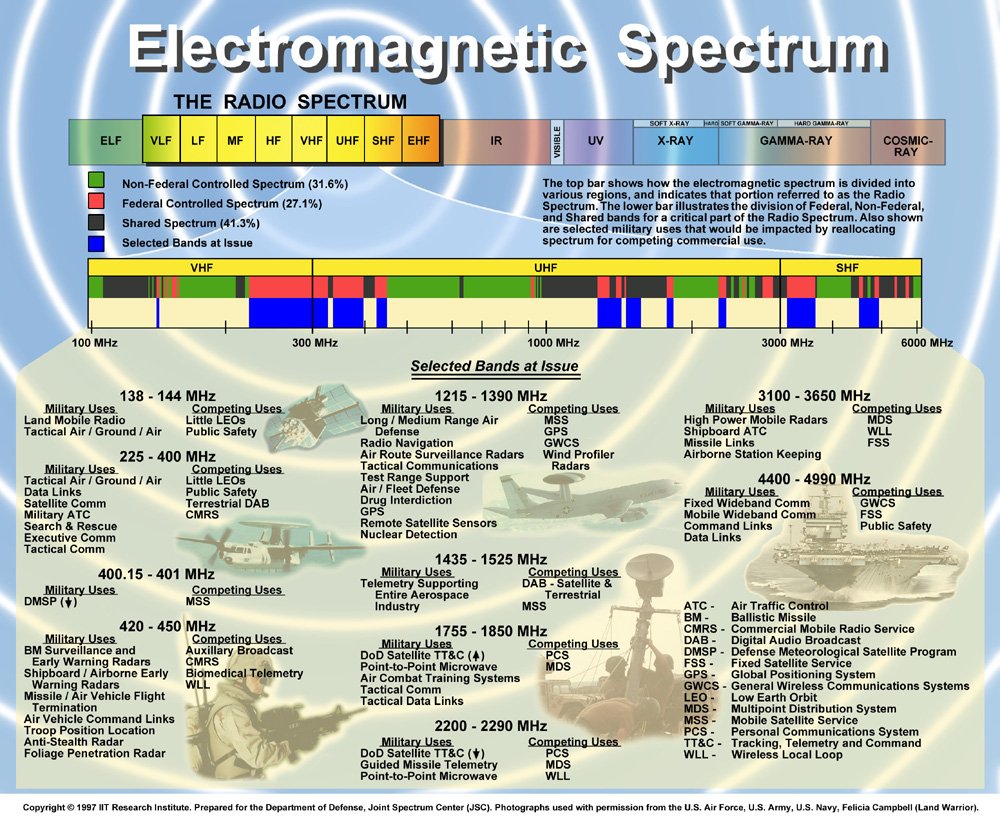

Technology has profoundly affected the manner in which states react to threats to their national security. Its effect on the imminence standard is mixed. Some technologies have made it easier to collect and act on intelligence, thus expanding the window of opportunity to preempt terrorist attacks. For example, the use of satellite surveillance and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, or “drones”) allows U.S. forces to track, observe, and engage individual terrorists remotely and without putting American service members in harm’s way.13 The ability to gather intelligence remotely and project power rapidly over long distances permits the United States to wait longer before initiating an attack because terrorist operations can be detected at earlier stages and individuals can be engaged on short notice by UAVs. In this sense, new technologies make the imminence standard more demanding. But technology can also compress the timeframe available for decision-making. For example, the decision to freeze financial assets of suspected terrorists must be made quickly and without notice due to the possibility the assets will be electronically transferred.14 Similarly, the advent of cyber-terrorism means terrorist groups can launch attacks on American infrastructure or financial institutions with no notice.15 These developments require the relaxation of the imminence requirement. Perhaps most importantly, technology can aid in decision-making by evaluating the imminence of potential attacks. Sophisticated computer programs can aid in weighing the risks and benefits of using force. In the near future, we may be able to develop systems that can gather intelligence, decide whether an imminent threat exists, and employ deadly force to eliminate the threat.16 Whether this type of technology can be used more widely will depend on whether it can incorporate the legal and ethical rules discussed in this article.

Conclusion

Developing a modern definition of imminence is an important and challenging goal for policy makers. Imminence is a concept that resists a strict legal definition and is better suited for practical determinations. In 2010, Nasser Al-Aulaqi filed a lawsuit in federal court seeking to prevent the U.S. government from killing his son, Anwar Al-Aulaqi, who had allegedly been placed on the U.S. government’s “kill list.”17 Al-Aulaqi wanted a court order stating that his son could be killed only if the government could show that he “presents a concrete, specific, and imminent threat….”18 The court held that it could not issue such an order because it was a political question: “the imminence requirement of [the plaintiff’s] legal standard would render any real-time judicial review of targeting decisions infeasible.”19 Despite being difficult for courts to apply, the administration should seek to develop a definition of imminence that will serve as a guide for future military actions against suspected terrorists. In doing so, it can provide the flexibility needed to respond to evolving threats while maintaining the respect of the international community.

George Fleming is a law student at Harvard Law School and former surface warfare officer in the U.S. Navy.

—————————————————————————————————————————

1. U.N. Charter art. 51 (emphasis added).

2. Daniel Webster, The Papers of Daniel Webster: Diplomatic Papers: Volume 1, 1841-1843, 62 (Kenneth E. Shewmaker & Anita McGurn eds., Dartmouth Publishing Group, 1983).

3. “Obama on bin Laden: The Full “60 Minutes” Interview” (May 2, 2011), available at http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-504803_162-20060530-10391709.html.

4. Model Penal Code § 3.04(1) (1962) (emphasis added).

5. See U.N. Charter art. 2, para. 4 (“All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.”). This understanding is at odds with the international realism school of thought. Under that theory, states use military force as a means of advancing their interests in an anarchic system. See generally Kenneth Waltz, Theory of International Politics (1979).

6. For example, during World War II, American fighters targeted and destroyed an aircraft carrying a Japanese official who planned the attack on Pear Harbor. See Harold Hongju Koh, Legal Advisor, U.S. Department of State, Keynote Address at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of International Law: The Obama Administration and International Law (Mar. 25, 2010). See also U.S. Army Field Manual, 27-10, The Law of Land Warfare, ¶ 31 (1956) (authorizing attacks on individual officers).

7. Department of Justice White Paper, Lawfulness of a Lethal Operation Directed Against a U.S. Citizen Who Is a Senior Operational Leader of Al-Qa’ida or an Associated Force (2013).

8. John Brennan, Assistant to the President for Homeland Sec. & Counterterrorism, Keynote Address at the HLS-Brookings Program on Law and Security (Sep. 16, 2011).

9. A very simple formula would compare (probability of success × benefits of success) with (probability of failure × cost of failure) + (cost of inaction).

10. Eric Holder, Attorney General, U.S. Department of Justice, Speech at Northwestern University School of Law (Mar. 5, 2012).

11. Mark Landler & David Sanger, U.S. and Israel Split on Speed of Iran Threat, N.Y. Times, Feb. 8, 2012.

12. See Holder speech, supra note 10.

13. See generally Jane Mayer, The Predator War, New Yorker, Oct. 26, 2009.

14. See, e.g., Exec. Order No. 13,382, 70 C.F.R. 38567 (2005).

15. See generally Matthew C. Waxman, “Cyber-Attacks and the Use of Force: Back to the Future of Article 2(4), 36 Yale J. Int’l Law. 421 (2011).

16. See, e.g., Kenneth Anderson & Matthew Waxman, “Law and Ethics for Robot Soldier,” Policy Review, 176 (Dec. 1, 2012). An example of this type of technology is the Navy’s AEGIS Combat System

17. Al Aulaqi v. Obama, 727 F. Supp. 2d 1 (2010). Anwar Al-Aulaqi was killed by an American UAV in 2011.

18. Id.

19. Id. at 72 (internal quotation marks omitted).