Where is the U.S. Navy Going To Put Them All?

Part 2: UUVs, Fire Scouts and buoys and why the Navy needs lot’s of them.

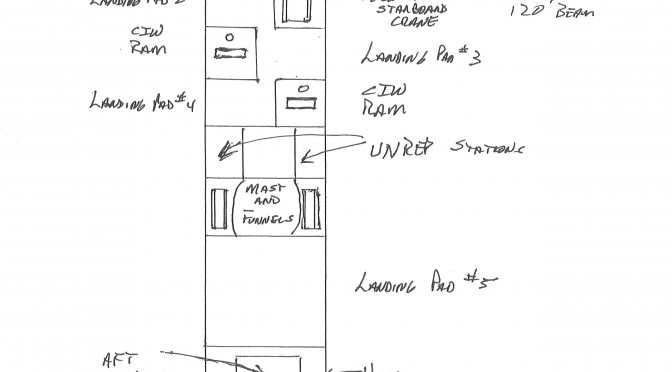

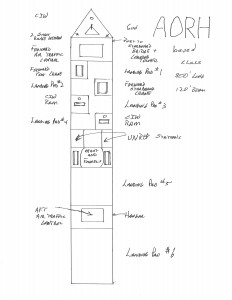

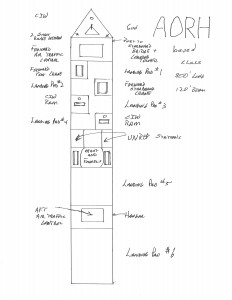

Sketch by Jan Musil. Hand drawn on quarter-inch graph paper. Each square equals twenty by twenty feet.

This article, the second of the series, lays out a suggested doctrine for the use of a UUV or dipping sonar installed on a ten foot square buoy deployed and maneuvered by Fire Scout helicopters. It is an incremental strategy, primarily using what the Navy already has in hand, but adding the use of a new buoy design, in quantity, combined with appropriate doctrinal changes and vigorously applying the result to the ASW mission. Read Part One here.

In getting this program underway the U.S. Navy can utilize existing sensors, primarily for prosecuting ASW, but also for mapping the bottom, underwater reconnaissance or other yet-to-be-envisioned missions. In practice, generating useful results is far easier to accomplish if the UUV or dipping sonar is routinely, though not exclusively, used with a tether so the data generated can easily be transmitted back to its mothership for analysis and use.

Ten-Foot Square Buoy (TFS Buoy)

At this point a brief description of the buoy noted above, to be deployed in scores at any given time, is in order. A set of eight hollow, segmented and honey-combed for strength where necessary tubes, say one foot in diameter, made of a 21st century version of fiberglass can be configured in a square. Stacking the ends of the tubes on each other log cabin style, but deliberately leaving the space between each pair of tubes empty creates as much buoyancy as possible, but very deliberately reduces freeboard. Whether the resulting buoy is equipped with a dipping sonar or UUV, both the sensors and the equipment needed to operate the tether, reel for the line and so forth are going to get soaked anyway. Simultaneously, we want a minimum of tossing about in various sea states as the sonar or UUV does its job or as a helicopter drops down to utilize a hook to grab the buoy and gently lift it clear of the water. Therefore, if the waves are moving between the pairs of tubes, this will substantially reduce the buoys unavoidable movement in the water, vastly easing the helicopters task in relifting it for redeployment.

A pyramid shaped area should be installed above the tubes to provide a double sealed compartment for the motor driving the reel and its power source. Another much smaller, triple sealed compartment for the necessary electronics, radar lure and antenna is needed just above it. At this point all that is needed is to add an appropriately sized steel ring at the top for the helicopter to snag each time it moves the buoy and we have an extremely practical piece of equipment to deploy, in large numbers and at a rather low price, across the fleet.

In the years to come, the Navy can incrementally add the ability to transmit and receive on different frequencies to measure the difference in time back to the emitting sensors thereby creating additional ways to monitor the underwater environment, detect targets and potentially be less intrusive when operating amongst our cetacean neighbors. By doing so we can build a much more sophisticated picture of surrounding water conditions such as local currents, variations in thermocline depth, salinity, water temperature at varying depths and so forth as well. A good computerized analysis of these data points and a doctrine of best practices to utilize this knowledge of water conditions will leave the mission commander in a position to make much better informed decisions on where to deploy his search assets next.

Utilizing tethered UUVs and dipping sonar with a suite of frequencies to listen and broadcast on opens up interesting opportunities for the ASW mission. By significantly expanding outward the range of ocean area being searched, the Navy can realistically anticipate creating the possibility of being able to establish a rough range estimate for a detected target. Spread the sonar emitters out far enough and the use of parallax kicks in. If there is just a little difference in vector to the target from two widely separated hunters they now have a working range number. This range estimate will almost certainly be nothing close to accurate enough to fire on, but it will certainly indicate a distinct patch of ocean to direct any orbiting P-8s or other fleet elements toward. Finding a needle in haystacks is a lot easier if you have a solid clue as to which haystack you should be searching. If Fire Scouts simultaneously drop dipping sonar equipped buoys around the area in conjunction with the UUV equipped buoys, then it will be even easier to find the metaphorical needle. For discussion purposes let’s say a Fire Scout starts its day by moving one UUV equipped and four dipping sonar equipped buoys, all transmitting locally to an ISR drone or ScanEagle just overhead, in relays, across the ocean. As the hours pass an enormous amount of ocean can be searched, further and further out from the task force, yet the buoys will be able to keep up with the task force as it travels, even in dash mode. With only one buoy being moved at a time, each one briefly out of the water as it is transported hundreds or a few thousands of yards, there will be a constant stream of much better data generated for the ASW team than the existing use of sonobuoys can provide. And the deployed equipment will be able to reliably function on station for many more hours than a manned helicopter team can provide.

Perhaps not at a 24/7 rate nor for days and days on end, but a task force with 15 Fire Scouts and 75 buoys deployed, potentially separated by many miles, has added multiple alternatives to the ASW teams.

It is suggested above that 15 Fire Scouts dynamically rotate 75 UUV or dipping sonar equipped buoys across the ocean. 15 and 75 are merely suggestions though. The real point is that to derive the greatest value from the newly developed UUVs and Fire Scouts the Navy needs to be thinking in terms of a dozen plus helicopters and scores of buoys at a time, regardless of the particular mix of equipment and sensors dangling beneath them. Again, think and operate in quantity.

Nevertheless there is always a problem or three lurking around that need to be dealt with. For now we have reached the point where we need to consider the question used as the title for the article – “Where is the Navy going to put them all?”

In the next article we will examine two new ship classes that can be used by the fleet to go to sea with the various types of drones, UUVs, Fire Scouts and buoys suggested, in quantity. Read Part Three.

Jan Musil is a Vietnam era Navy veteran, disenchanted ex-corporate middle manager and long time entrepreneur currently working as an author of science fiction novels. He is also a long-standing student of navies in general, post-1930 ship construction thinking, design hopes versus actual results and fleet composition debates of the twentieth century.

CIMSEC content is and always will be free; consider a voluntary monthly donation to offset our operational costs. As always, it is your support and patronage that have allowed us to build this community – and we are incredibly grateful.

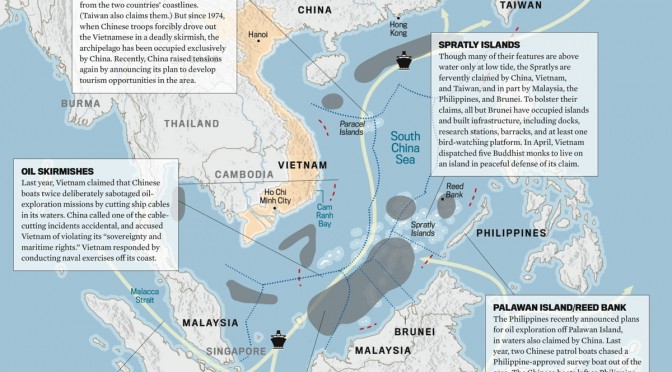

This year, CIMSEC’s DC chapter is holding a series of participatory events focusing on different maritime security challenges and disputes. To do so, we’re using an experimental event format with elements of wargamming, simulation, ideation, and crowd-sourcing to elicit creative insights. Our live events will be followed by online crowd-sourcing phases in which the outputs the CIMSEC community at large is invited to participate.

This year, CIMSEC’s DC chapter is holding a series of participatory events focusing on different maritime security challenges and disputes. To do so, we’re using an experimental event format with elements of wargamming, simulation, ideation, and crowd-sourcing to elicit creative insights. Our live events will be followed by online crowd-sourcing phases in which the outputs the CIMSEC community at large is invited to participate.