This article originally featured on Bharat Shakti. It may be read in its original form here.

By Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan, AVSM & Bar, VSM, IN (Ret.)

The year 2022 arrived as a harried harbinger of tidings of war and woe in the Indo-Pacific — a geo-strategic region central to the security calculus of both, regional and extra-regional players. From the United States of America to Japan, strategic advisers and military practitioners began reading-up their several carefully-prepared contingency plans, each focused upon the increasingly violent writhing of the Chinese dragon.

Although the danger-signs of a precipitous economic decline within the People’s Republic had appeared even before 2015, the sheer speed of contraction of the Chinese economy took the world completely by surprise. The internal repercussions within China were so extreme that news of the violent unrest within the Middle Kingdom easily transcended the efforts made by the CCP to keep matters under wraps. Widespread rioting became commonplace as socio-economic fault lines — centred upon income inequality, curbs on rural labour becoming permanent urban-dwellers, and the huge economic disparity between southern coastal cities and the hinterland — could no longer be papered over by ‘gloss’ and ‘bling.’

The CCP’s recurring nightmare of regime-collapse threatened to become a grim reality. Faced with increasingly belligerent responses from the USA, India, Vietnam, the Philippines — and even Indonesia — to its earlier attempts to convert the South China Sea into a Chinese lake through machinations such as the Nine Dash Line, the Chinese leadership turned to the oldest trick in the book to reunite the country. It pointed to a ‘malevolent’ axis of alignment between India, the USA, Japan and Australia as being responsible for a series of carefully orchestrated actions designed specifically to stunt and reverse China’s economic miracle. Indian duplicity was specifically and repeatedly referred-to and, in the ensuing vituperative polemics, much was made of teaching ‘upstart’ India a lasting lesson. Chinese media was repeatedly drawing the people’s attention to Indian adventurism along the still-unresolved border.

As a supposed ‘restrained and proportionate response’, deep incursions by Chinese troops began across the entire Sino-Indian border. Most worrying to India was the significant Chinese build-up in Demchok and in the Chumbi Valley. Paying scant regard to the protestations of Bhutan, Chinese troops had begun occupying the western extremities of Bhutan that they had been long been claiming as their own. This widened the ‘point’ of the Chumbi Valley and the danger to India’s ‘Chicken’s neck’ was seen as being clear and present.

Over the past few years, Indian mountain infrastructure had certainly improved, but was far from ideal. Nevertheless, New Delhi directed its newly raised Mountain Strike Corps (its embryonic state notwithstanding), to deploy in the Gaygong-Geegong gap. IAF Forward Air Bases in Nyoming, Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO) and several more in Arunachal Pradesh were brought up to full combat capability and ammunition pre-positioned. The roar of Su-30 aircraft became incessant at Tezpur.

Many forward-looking Indian planners had high hopes of the Indian Navy being able to achieve a ‘strategic outflanking’ of the Chinese at sea — yet, the Chinese Navy seemed to have pre-empted matters: In the Gulf of Aden, the 44th Chinese anti-piracy Escort Force, comprising two Luyang-II (Type 052C) destroyers, one Jiangkai-II (Type 054A) frigate and one Fuchi Class (Type 903A) replenishment ship, was supplemented by a significant flotilla consisting of four Luyang-III (Type 052D) destroyers led by the Changsha, six Jiangkai-II frigates, an Underway Replenishment Group (URG) comprising two Fuchi Class ships, and, oneShang Class SSN. The ships berthed at Djibouti while the SSN, having called at Karachi, was last reported at the newly-developed submarine berth at Gwadar.

Luyang III: Chinese Missile Destroyer (Picture Courtesy: Chinese Military Review)

Just north of Indonesia’s Natuna Island, a confirmed sighting was registered of a Chinese amphibious flotilla centred upon the aircraft carrier Liaoning, along with three Luyang-III destroyers, three Sovremenny Class destroyers, three Jiangwei-II and four Jiangkai-I Class frigates, apparently escorting four Yuzhao Class LPDs and accompanied by two Type 901 Fast Combat Support SHIP (FCSS). Three Zulfiquar Class frigates of the Pakistan Navy — an unusually large number — had also been deployed with the ‘Coalition Task Force 150’, while three Agosta-90B submarines (all capable of Air-Independent Propulsion) were notably absent from any of Pakistan’s naval harbours. It was manifestly clear that battle lines had been drawn….

How and under which circumstances the Government of India might realise and decide that the Union of India — in its entirety (as opposed to just the Army) — was in a state of armed conflict against the People’s Republic of China is a matter of conjecture and debate. Yet, the above scenario provides a plausible enough backdrop against which the state of advancement of Indian warships and warship-building needs to be examined.

Tonnage is a very good indicator of the ability of a warship to endure the violence of the maritime environment — something that generally increases with distance from the coast. Thus, warships of heavier displacement-tonnage are more likely to be suitable for protracted deployments in ‘blue waters’ than are those of lighter displacement-tonnage.

INS Kolkata (Picture Courtesy: Indian Defence News)

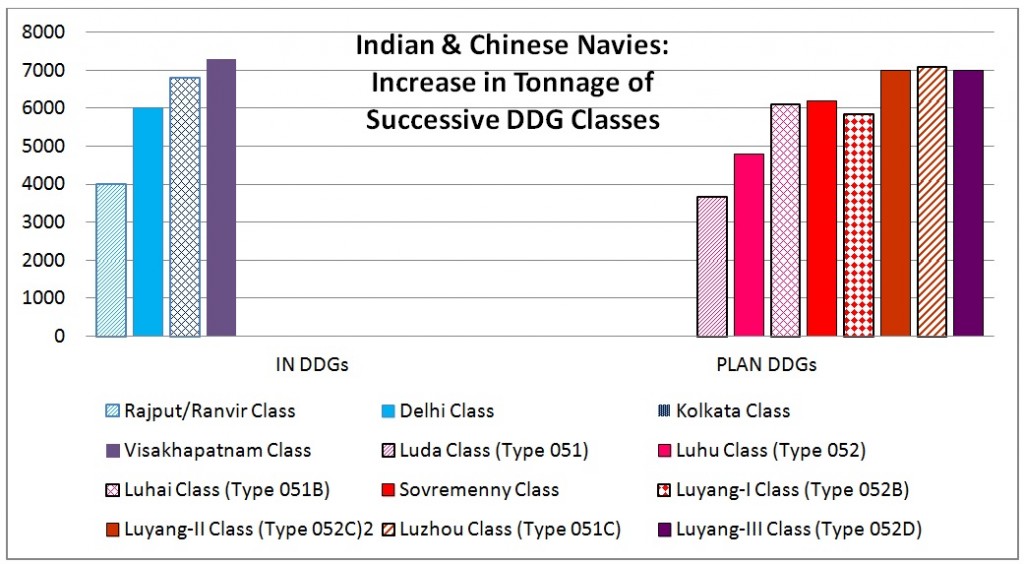

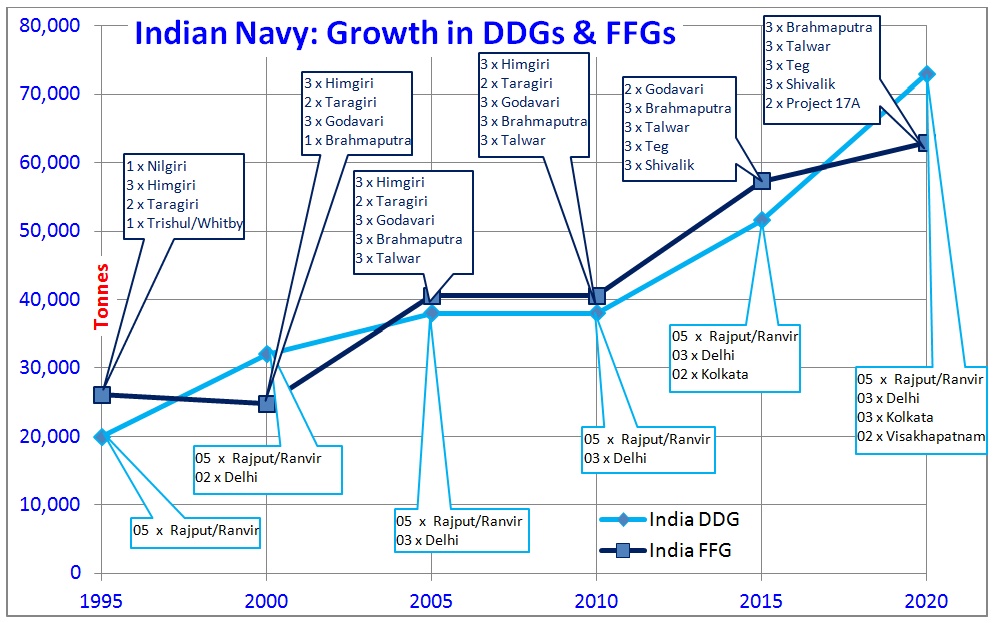

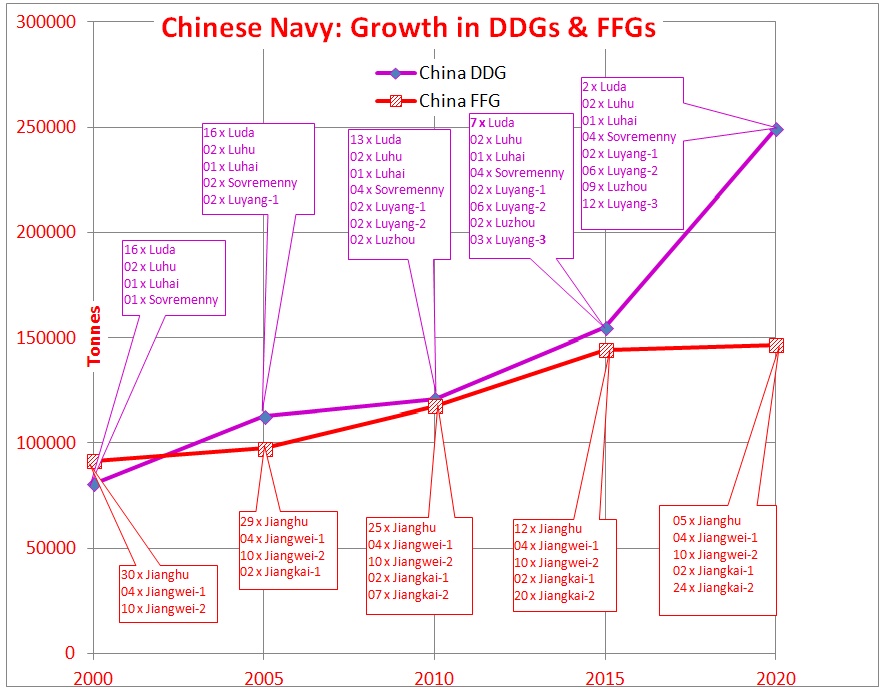

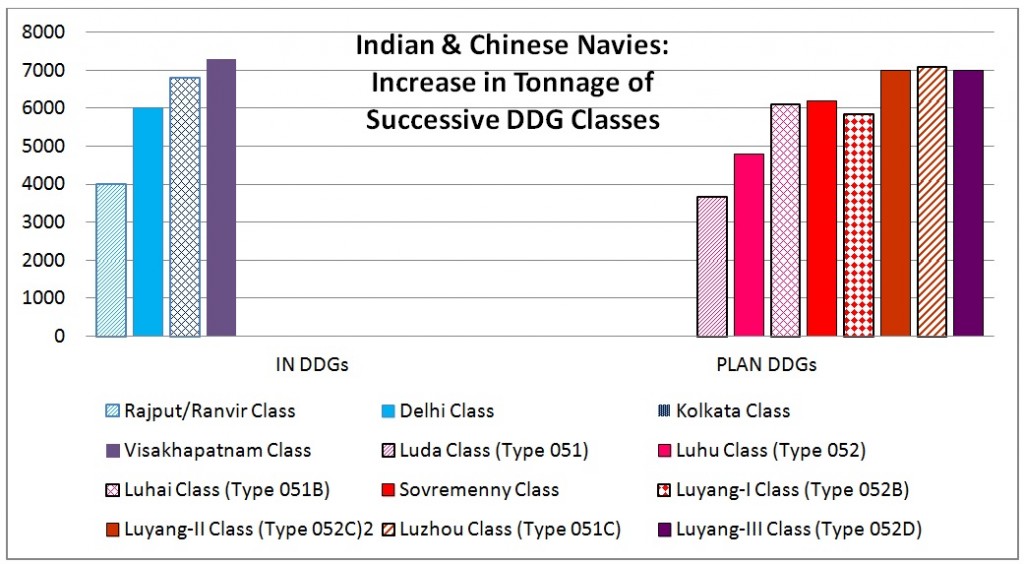

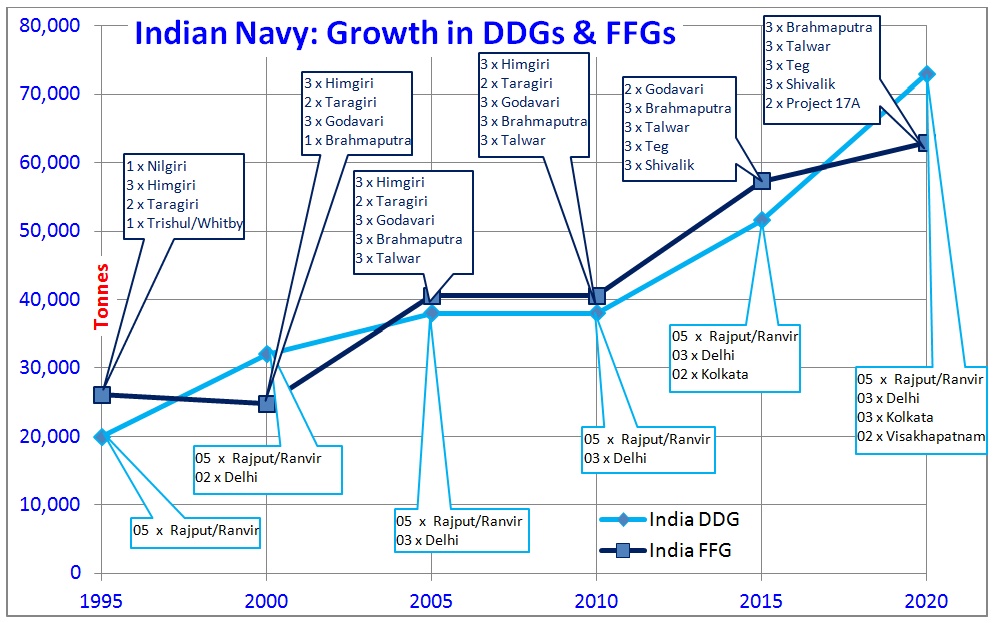

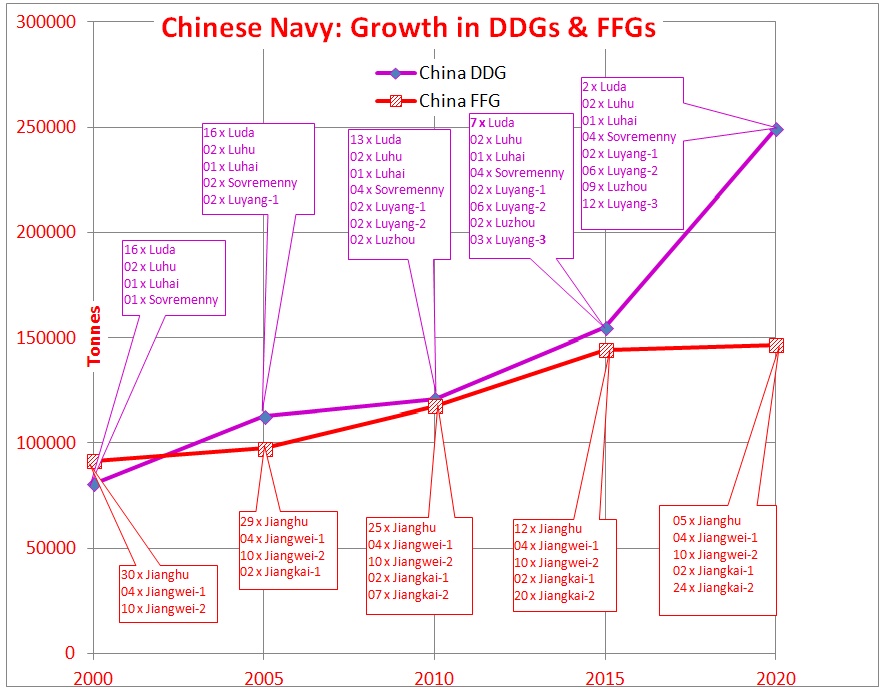

In this regard, the tonnage of the Indian Navy’s frontline surface-combatants (guided-missile destroyers and frigates) — taken individually as well as collectively over the 25-year period from 1995 to 2020 — shows a consistent and impressive increase. However, the Chinese Navy, too, has been demonstrating a nearly identical trend. This is a clear sign of the steady consolidation of the ‘Blue-water’ capacities of both navies, and may be readily discerned from the following graphs. Contemporary DDGs in both navies have displacement-tonnages in the region of 7,000 tonnes, making them eminently suitable for protracted deployments in distant waters. It may also be seen that the Indian Navy has far fewer classes of Guided Missile Destroyers (DDGs) than does its Chinese counterpart.

The reverse is true when it comes to Guided Missile Frigates (FFG). Here, the Indian Navy’s contemporary classes are certainly pushing the limits of what might reasonably be termed a ‘frigate.’ In most countries, ships of the Shivalik Class and those of ‘Project 17A’ to follow — both classes displacing 7000 tonnes or more — would be certainly categorised as ‘destroyers.’ Were this to be done, the number of ship-classes in both categories (DDGs and FFGs) would be very similar in both navies.

INS Satpura.

The past and projected growth of the Indian Navy in terms of numbers of DDGs and FFGs over the period from 1995 to 2020 may be seen through the following graphical depiction, which details the numbers of warships in each class of destroyers and frigates respectively.

It is important to note that while the tonnage of the individual warship-classes that constitute each navy has been rising, and while

there is not much to give or take between the comparative tonnages of Chinese and Indian frigates or destroyers, it is the stark disparity in the sheer numbers of Chinese and Indian warships that make the overall tonnage that each navy can put to sea so different from each other. The huge impact that these ‘numbers’ have in terms of the overall tonnage that both navies can put to sea may be readily discerned once these are plotted on the same scale.

What all this brings out quite starkly is that although Indian warship construction / induction is certainly picking-up and although the tonnage-trend is a healthy one, it is, nevertheless, very nearly a case of ‘too-little-too-late.’ Indian ship-building has to show a dramatic increase of the type shown by Chinese shipyards, most especially in the period after 2010.

This, of course, is a realisation that is somewhat more sobering than the breezy optimism that comes embedded in the official pronouncements that emanate from New Delhi. Despite the proclivity of our defence shipyards to ‘cut-off their noses to spite their faces’ by refusing to accept their capacity-limitations and encourage private players, there is an urgent need for greenfield shipyards in the country to either build relatively low-end platforms so as to free-up capacity in the more established defence shipyards, or to take up construction of major surface-combatants themselves. The latter could, perhaps, be under a ‘prime system-integrator’ model as was done for the Daring Class ‘Type 45’ guided-missile destroyers of the British Royal Navy. As such. there is, enormous scope for private players in the national effort to ratchet-up numbers in the Indian Navy’s DDG and FFG holdings.

In the interim, the Government of India and its Navy will have to rely upon nimble-footedness at the strategic level as well as at the level of operational art, so that even if a conflict with China arise, the entire numerical strength of the principal combatants of the Chinese Navy are not capable of being arrayed against it en masse. The plans and strategems for this, are, of course, subjects for a far more detailed analysis.

In the interim, the Government of India and its Navy will have to rely upon nimble-footedness at the strategic level as well as at the level of operational art, so that even if a conflict with China arise, the entire numerical strength of the principal combatants of the Chinese Navy are not capable of being arrayed against it en masse. The plans and strategems for this, are, of course, subjects for a far more detailed analysis.

Yet, there is some cause for quiet satisfaction, too. For instance, the overall combat capabilities — comprising the various weapon-sensor suites, the software-intensive integration systems, the integral-air capacity, and, the propulsion and power-generation plants — of both, contemporary Indian guided-missile destroyers (DDGs) and guided-missile frigates (FFGs) compare quite favourably with those of the Chinese Navy. In a combat encounter between major surface combatants, the Indian Navy is very likely to acquit itself well. For this, the uniformed and civilian segments of the Indian Navy (they are very nearly equal in numbers), the DRDO and our ship-builders must be given much credit. That said, naval warfare is typically one in which the ‘hunter’ and the ‘hunted’ switch roles with disconcerting frequency and often operate in entirely different mediums. Thus, the capability of current and future Indian warships must also be assessed against air threats (including anti-ship missiles) and underwater threats emanating from both, conventionally and nuclear-propelled submarines.

Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) within most parts of the northern Indian Ocean — most especially in the Arabian Sea — is adversely impacted by a ubiquitous negative temperature-gradient. This significantly shortens the detection range of hull-mounted sonars. On the other hand, towed-array sonars and ship-mounted variable-depth sonars impose often-unaffordable operational penalties in terms of maneuverability and speed — quite apart from a host of maintenance-related technological challenges that industry needs to wrestle with.

Scorpene submarine (Picture Courtesy: Daily Mail, UK)

Indian FFG and DDG ship-designs have long featured the carriage of two 10-13 tonne multi-role / ASW helicopters aboard every such platform. An ASW helicopter, equipped with a variable-depth sonar with high-end processing capabilities, sonobuoys, and a good EW suite, is the optimum platform for seaborne ASW and the Navy requires these in adequate numbers so as to take advantage of the potential offered by excellent ship-design. For the present, the absence of multi-role helicopters has rendered this design-advantage null and void. Much promise was initially held out by the indigenous ‘Advanced Light Helicopter’ (ALH) Dhruv. However, the technological challenges of folding rotor-blades and minimising the downwash while the helicopter is in hover continue to frustrate efforts to embed this helicopter within the integral-air capacity of the Indian Navy.

As and when our otherwise very-capable surface-combatants need to operate in a combat-environment characterised by a substantive subsurface threat, this lack of integral ASW helicopters might well prove decisive. In contrast, Chinese ships have a carrying-capacity of just a single helicopter, but successful reverse-engineering of the French Dauphin has resulted in the Harbin-Z that is integral to Chinese warships.

Perhaps the most telling factor weighing in favour of the ‘reach’ of the Chinese Navy is its impressive holding of refuelling-tankers and stores/ammunition-supply ships, particularly those capable of ‘underway replenishment.’

Qiandaohu Ship (Picture Courtesy: en.people.cn)

The six Qiandaohu Class (Type 903A) replenishment vessels displace 23,000 tonnes, compared with the two 19500-tonne replenishment-tankers of the Indian Navy’s Deepak Class. Although the five Dayun Class (Type 904) stores-supply ships of the Chinese Navy are incapable of underway replenishment, they do add significantly to their Navy’s amphibious follow-on capacity. Seeking to catch-up, the Government of India had floated a global Request for Information (RFI) for the construction of five large 40,000-tonne ‘Fleet Support Ships’ for the Indian Navy. Although the delivery of the first ship has been specified as 36 months (with subsequent ships being delivered at six-monthly intervals), there is little evidence as yet of any significant progress. This notwithstanding, opportunities for Indian industry in terms of the equipment-fit of these ships is, once again, enormous.

In conclusion, if India is to be able to handle the fictitious 2022-scenario that this brief piece began with, there is an urgent need to address the shortfall in numbers of major-combatants and fleet-support ships. It is true that over 45 warships are currently building in Indian shipyards, but the rate of production is painfully slow and as a consequence, the numbers may not be enough in the available time before such a scenario shifts from absorbing fiction into frightening fact.

Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan (ret.) retired as Commandant of the Indian Naval Academy at Ezhimala. An alumnus of the prestigious National Defence College.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of BharatShakti.in)