By Zachary Abuza and Nguyen Nhat Anh

On 2 May, the French amphibious assault ship FS Tonnerre arrived in the Cam Ranh International Port (CRIP) for a four day visit. It was the third international visit to the newly established CRIP, nee Cam Ranh Bay, following the mid-March visit of a Singaporean naval vessel and a mid-April visit by two Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force ships. These three visits reflect Vietnam’s strategic interests, most importantly, the development of an omni-directional foreign policy. While much attention will be paid to President Obama’s visit to Vietnam this month, it is important to note both how far bilateral relations have come, but also how much they are only a piece of Vietnam’s overall strategic framework.

The decision to give Cam Ranh the moniker “International Port” was a strategic one. Hanoi has long been called on to open up the port to foreign vessels transiting the region, but wanted to make sure that it was not aimed at any one country. Thus the port, which is one of the finest deep-water ports in the entire region and is full of new construction after the inauguration such as a new berthing area, pier, quay wall, and was opened up to all on a “commercial basis.” This is in line, if not a creative work around, with Hanoi’s “3 Nos” foreign policy (no alliances, no foreign military bases, and no policies that could be construed as being directed against any one state). The argument that any one foreign country could try to gain exclusive access to the port is nonsensical.

Indeed, in bilateral defense talks held at the end of March 2016, Vice Minister of Defense Nguyen Chi Vinh said that Vietnam had actively invited Chinese vessels to visit Vietnamese ports, including CRIP. Even though it was an unpopular move domestically, it signals the leadership’s intention that CRIP not be directed against any one country.

While it is clear that Vietnam-U.S. defense cooperation has deepened considerably over the last few years and will continue to do so, both sides seem to be content on the pace with which the relationship is moving for various reasons.

Vietnam clearly has a strategic interest in a more robust U.S. presence in the region, and has actively championed the right of U.S. Naval vessels to conduct freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs), including past features that Vietnam itself claims and occupies. Vietnam also looks to the United States as the only thing between China and the declaration of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ).

However, although Hanoi is keen to further deepen ties with the United States, there remain many real impediments, including history, the continued legacy of Agent Orange, and the enormous costs associated with the cleanup of Bien Hoa, and criticism over human rights. Indeed, this year, Hanoi responded to the U.S. State Department’s annual human rights report, calling it “biased,” something it has not done and downplayed in the past few years. Furthermore, despite its embrace of the Trans Pacific Partnership, Hanoi is cautious about growing too close to the United States in the security realm, for fear of provoking a harsh reaction from China, hence its intention of displaying CRIP as a neutral, open-to-all port.

From 22-24 May, President Barack Obama will visit Vietnam, reciprocating the historic July 2015 visit to the United States by Vietnam Communist Party chief Nguyen Phu Trong. While many hope that President Obama will fully lift the arms embargo, others argue that Vietnam simply has too many human rights abuses to merit a full lifting. Indeed, his Secretary of Defense recently endorsed lifting the embargo in a Congressional hearing with Senator John McCain, a long proponent of ending the embargo. In early May, right before Obama’s visit, Vietnam hosted a defense symposium to which top U.S. arm corporations, such as Boeing and Lockheed Martin, were invited. This will be more of a symbolic gesture, but in diplomacy, especially in such a historically fraught relationship, symbols matter.

But even still, limits exist. There are longstanding concerns about selling advanced technology to Vietnam for fear that it will be shared with Russia. Again, human right issues also interfere with the decision. Nevertheless, this is not to say that Vietnam’s purchase of U.S. weapons is impossible.

The one area that does seem ripe for sales is maritime aviation capabilities, something that the U.S. does have a stark comparative advantage in. Vietnam has expressed an interest in a stripped down P-3 Orion. In April 2016, a group of Vietnamese naval officers visited U.S. Patrol Squadron 47 in Hawaii and notably toured a P-3C in order to better understand its capability. Vietnam has also seen the P-3 in action in January 2016 during a joint HADR exercise between Vietnam and Japan. Boeing has suggested that one of its Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) suites would fit Vietnam’s needs.

Despite the regular presence of U.S. Naval vessels, which spend some 700 ship days a year in the South China Sea, and the recent visit by the USS Stennis to the Philippines, and the recent refusal of port access in Hong Kong by China, to date no U.S. vessel has called on CRIP.

Furthermore, Vietnamese rules stipulate that foreign naval vessels, including those of the U.S., can only call on Vietnamese ports once a year. Nevertheless, U.S. logistical ships have visited the port before for repair and maintenance service. In June 2012 USNS Richard E. Byrd, a Military Sealift Command supply ship, stopped at Cam Ranh’s repair facilities, and then-Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta gave a speech on board the moored ship, promising a stronger relationship between the two nations. The U.S. Navy has used their port call annually since 2009, albeit not at Cam Ranh Bay. Furthermore, when reporting the inauguration of CRIP, Vietnamese official media mentioned the possibility of U.S. aircraft carriers calling on the port by mentioning that CRIP can “accommodate military and civilian ships like aircraft carriers of up to 110,000 DWT (deadweight tonnage).” Hence, it is likely that a U.S. Navy ship will call on Cam Ranh Bay in the near future.

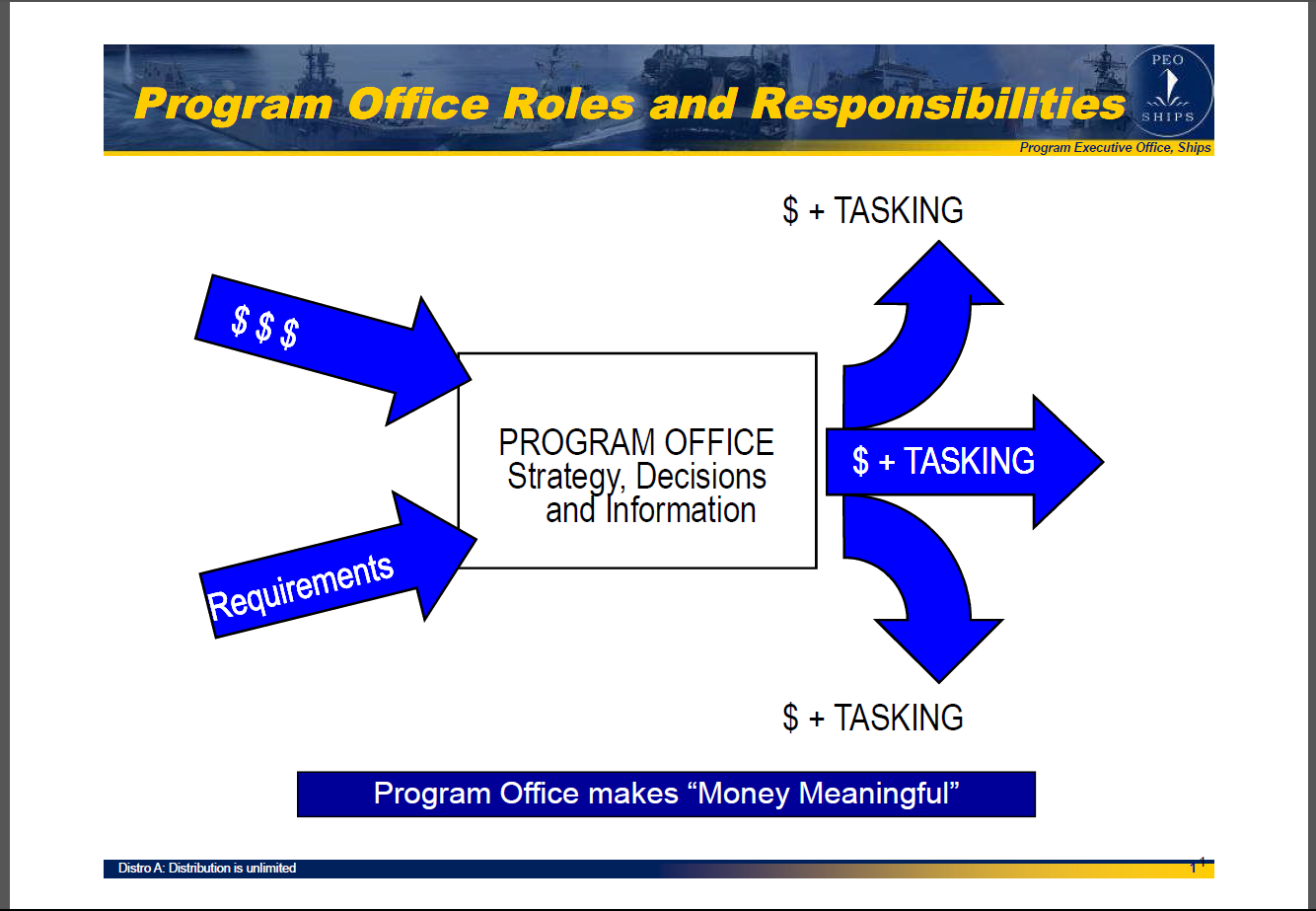

In addition, the U.S. government has awarded Vietnam $40.1 million in FY2015-16 as part of its Maritime Security Initiative in order to “bolster its maritime Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) and command and control within Vietnam’s maritime agencies.” The funding will also support the purchase of maritime defense equipment and support training and bilateral HADR exercises to improve interoperability.

The visit by the Singaporean naval vessel should have come as no surprise. ASEAN – for all of its faults and limitations – remains the cornerstone of Vietnamese foreign policy. It works assiduously to counter China’s aggressive moves to divide the grouping, especially ahead of the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s expected ruling. Vietnam and Singapore have pledged to deepen ties and have suggested future bi and multi-lateral defense exercises.

Soon after, Vietnamese naval vessels and special forces soldiers participated in a regional counter-terrorism and anti-piracy exercise with Singapore, Brunei, Thailand and Indonesia. Interestingly, Vietnam sent HQ-381, a BPS-500 type missile corvette instead of its Gepard frigates. The HQ-318 was the first missile corvette built domestically in Vietnam in 1999, and it underwent capability upgrades in 2014. Vietnam has also increased its participation in multilateral exercises, including sending Hospital Ship 561 to the 2016 Komodo naval exercises in Indonesia in April 2016. Vietnam has extended maritime cooperation to entirely new partners as well, including a five day on-shore multilateral course by the Royal Navy’s Maritime Warfare School on EEZ enforcement.

The visit by the French ship capped a week of the re-emergence of France as a player in Asian security, with the agreement in principle to supply Australia with 12 Barracuda submarines; beating out the Japanese Soryu-class. But the presence of one of France’s largest vessels at CRIP also suggests the potential for defense deals with Vietnam, which has hinted that it wants to reduce its dependence on Russia for its advanced weaponry. Vietnam has already purchased military lift planes from the French-led Airbus consortium. SIPRI, in its arm transfer database, shows that Vietnam has taken delivery of Exocet anti-ship and MICA anti-air missiles from France for its Dutch SIGMA-9814 corvettes; yet, as the negotiation for the corvettes seems to have been suspended, the fate of these missiles is uncertain. Reuters also reported that the Vietnamese military is currently in talk with Dassault on the Rafale multirole fighter as a possible replace for its antiquated but numerous MiG-21s. However, the Rafale’s high cost makes this procurement less likely.

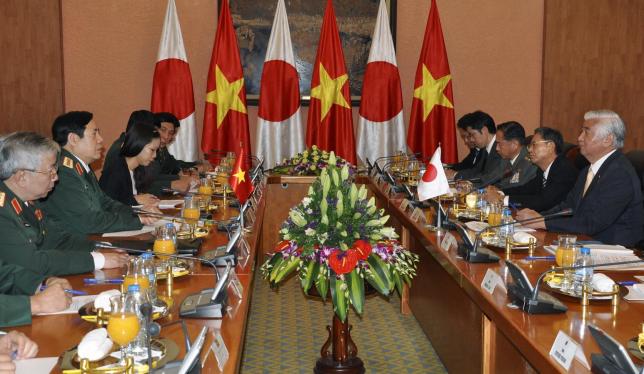

But it is the relationship with Japan that portends the greatest potential. There have now been six high level strategic dialogues, and Japanese ships have made some nine port calls, the majority of which happened in the last five years. There are routine high level engagements. Although Japan has not sold any weapons to Vietnam, in 2014 it pledged to transfer six maritime patrol craft; the last were delivered in November 2015.

The potential for deeper ties is clearly there. A meeting between the respective foreign Ministers in early May 2016 led to calls for deepened defense relations as well as the provision of more maritime patrol craft. As Japan experiences the loss of the Soryu class vessels sale to Australia, Tokyo still needs a major arms sale to break into the world of the global arms industry. But while Japanese equipment is expensive and r technology transfer is unlikely, the defense relationship, including recent HADR operations, is growing so quickly that it might become a natural byproduct.

Both countries have called for a rules-based system in the South China Sea. Both would like each other to step up their respective operations in the South China Sea. Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc recently called on Shinzo Abe’s government to make “effective efforts” in the South China Sea, but there are limits. Vietnam in unlikely to be overly confrontational towards China. And while many have called for Japan to join U.S. FONOPs, that is unlikely, simply as China has the ability to escalate its operations in the contested waters around the Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands. Intercepts of Chinese planes in Japan’s southwest quadrant alone already account for over 50 percent of overall intercepts of foreign aircraft. In 2015, there were 571 intercepts of Chinese planes, a 23 percent increase from 2014, taxing the Japanese military.

Despite these improvements and deepening cooperation with new defense partners, it is the bilateral defense relationship with Russia that remains the strongest. Newly elected Minister of National Defense Ngo Xuan Lich made his first overseas trip to Russia, where he reiterated that Vietnam will continue to rely on Russia for much of its weaponry and advanced training. Newly elected Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc will also make Russia his first foreign destination in mid-May, ahead of President Obama’s visit.

Vietnam’s third Gepard class frigate was recently floated in a Russian shipyard, with the fourth to be launched soon and delivered by September. There are reports that Vietnam will order another two, a total of six, while it has increased production of Molniya class missile ships under license from Russia. Five out of six Kilo submarines that Vietnam ordered from Russia have been delivered, and Russia is helping Vietnam construct the submarine base at Cam Ranh as part of the deal. Vietnam’s recent announcement that it was moving the Ministry of National Defense’s Ba Son Shipyard to a new location, increasing its production capabilities to 2,000 dead weight tons, also suggests increased domestic production under further Russian license.

When Vietnam purportedly “invited” Russia back to Cam Ranh, it should not be taken as meaning a reopening of their Cold War era naval base, which closed in 1991, but simply as a commercial user of CRIP facilities. Nonetheless, in 1993 Moscow and Hanoi signed a 25 year agreement that allowed Russia to continue using a facility in Cam Ranh Bay for limited signals intelligence gathering. More recently Russia has deployed aerial refueling tankers from CRIP to support bombers that have flown “provocatively” near US airspace in Guam. U.S. calls on Vietnam to restrict such operations have fallen on deaf ears. Furthermore, in 2014, the procedure for Russian ships calling on Cam Ranh Bay was simplified: they only have to notify Vietnamese authority before doing so.

While there have been occasional reports that Vietnam wants to diversify its sources of advanced weaponry, the reality is Russian equipment is tried and true, very cost effective, and the Vietnamese have long trained on it. Most importantly, the Russians transfer a lot of technology to Vietnam, which produces an array of missiles and ships under license. Vietnam’s relationship with India, also gives it access to the advanced Brahmos anti-ship missiles developed with Russia. This is an enduring strategic defense relationship.

Yet, small diplomatic rifts between Vietnam and Russia have emerged, in particular over Moscow’s support for Beijing over the South China Sea and Permanent Court of Arbitration’s forthcoming ruling. In April 2016, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov commented in an interview that claimants in the South China Sea dispute should resolve the matter among themselves and not attempt to internationalize the issue. Vietnamese Ministry of Foreign Affairs immediately rebutted Lavrov by announcing that the dispute should be “settled by all countries concerned,” not simply through bilateral negotiation. Notably, Lich’s visit to Russia occurred only two weeks after this incident. It should be closely watched whether this diplomatic rift will negatively affect Moscow-Hanoi defense relationship in any way.

In sum, since the 12th Party Congress in January 2016, and the early election of key state leaders to their posts ahead of President Obama’s visit, Vietnam has continued with their defense policy: a cautious attempt to bolster defense relations with regional and extra-regional states, the gradual diversification of its arms suppliers, and partaking in joint exercises. While it has brought a lot of new equipment online, giving the country unprecedented power projection capabilities, it is yet to be seen whether they have developed a corresponding doctrine. While no one should underestimate Vietnam’s will and capability to act in self-defense, that robust strategic culture has faltered at the hands of China’s maritime-militia and Coast Guard sovereignty enforcement operations and island construction. However, as Vietnam’s capability improve, it remains cautious about provoking a harsh reaction from Beijing. Yet, at the end of the day, Hanoi’s primary concern continues to be regime survival. The government responded quickly when environmental protests went national, and the regime seems very concerned regarding its ability to control its very wired and socially active population.

Zachary Abuza, PhD, is a Professor at the National War College where he specializes in Southeast Asian security issues. The views expressed here are his own, and not the views of the Department of Defense or National War College. Follow him on Twitter @ZachAbuza.

Nguyen Nhat Anh is a student of International Political Economy at the University of Texas at Dallas. You can follow him on Twitter @anhnnguyen93.

Gepard, Molniya class warships in Cam Ranh naval base. TTVNOL.com.