By Millard Bowen and David Andre

In January 2016, the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) issued A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority, which defined the current operational environment and laid out our Navy’s most pressing challenges within a framework of three interrelated global forces. These global forces—the classic maritime system, the global information system, and the increased rate of technological creation and adaptation—require the Navy’s Intelligence Community (IC) to adapt for the 21st Century.

Of the four Lines of Effort identified in the CNO’s Design, the Navy IC can directly affect three: Achieve High Velocity Learning at Every Level, Strengthen our Navy Team for the Future, and Expand and Strengthen Our Network of Partners. The fourth Line of Effort— Strengthen Naval Power at and From Sea — will derive direct advantages through Navy IC advancements in the other LOEs. Within this context, this paper identifies three challenges and proposes solutions to help the Navy IC effectively execute the CNO’s Design.

Challenge 1: Disseminate Ideas and Information Across the Intelligence Community

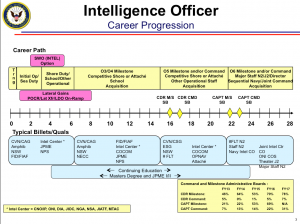

There is a contradiction inherent in the Navy IC’s professional development between generalization and subject matter expertise. On one hand, the Navy IC is a relatively stove-piped community, with little overlap between the disparate specialties and geographic commands that constitute the larger naval intelligence enterprise. At odds with this is a development paradigm for Intelligence Officers that prizes geographic diversity and job variety. In practice, this means that Intelligence Officers repeatedly find themselves at the bottom of the learning curve. Tour lengths and career progression permit only a modicum of regional or topical expertise before moving on to different problem sets.

This creates an environment where the only Subject Matter Experts (SME) on a given target or region are often civilians at shore-side facilities where their expertise is directed (or constrained) to a select few leaders in the IC and greater DoD enterprise. Coupled with this situation is the current trend where most Intelligence Officer training resides at the unit level, allowing operational tempo and personality types to de-standardize the frequency, quality, and accuracy of the training.

The Navy lacks a consistent, IC-wide ability to ensure sustained familiarity with current intelligence, technology developments, and emerging challenges and threats. Aside from the baseline knowledge established in the Navy Intelligence Officer Basic Course (NIOBC), the majority of junior Intelligence Officers are defined by their assignments and therefore lack a strong grasp of the greater body of information in the IC. It is critical that Intelligence professionals provide warfighters and decision-makers context and probability; this paper contends that our current professional development does not develop this capability. In a future electromagnetic- (EM) degraded warfighting environment, relevant intelligence expertise needs to be available organically, across pay-grades and platforms. There will be no time for an Intelink hunt.

Solution: Use Modern Technology to Disseminate Practical Knowledge IC-Wide

To address these shortfalls, the Navy IC needs to use new technology to share ideas and information efficiently. The intent is not to turn generalists into SMEs, but to bridge knowledge gaps and prepare Intelligence Officers for the full array of jobs available. Using SMEs to develop the baseline knowledge of the community increases information flow and encourages innovation. To pass new information, the IC has traditionally relied on CDs and e-mails with uncertain distribution, messages with no mechanism to confirm readership, and ad-hoc training subject to the variations of trainers and the training environment.

An example of a periodic Navy audio series, the CNO’s podcast, Soundings. Click to listen to the February 15, 2017 episode on the core attribute of toughness.

The IC should augment these traditional methods with the creation of periodic video and/or audio lecture series to instruct the Navy IC on current information. Use the example of a podcast or TED Talks where an Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) or Joint Intelligence Operations Center (JIOC) SME uses audio and visual aids to provide the ground truth on myriad topics to Navy Intelligence personnel worldwide.1 Instead of being constrained by the unbalanced knowledge that intelligence professionals develop individually, leverage SME knowledge to educate the broader community—effectively turning a weakness into strength. Underpinning this effort will be a central repository where the briefs reside, readily accessible to the fleet. These products will allow Intelligence Officers and enlisted Sailors to arrive on-station familiar with ongoing threats, trends, and maritime security challenges wherever they are assigned. This will enable high velocity learning by accelerating the dissemination of expertise and leveraging specialization to enhance the knowledge of the greater intelligence community.

We propose that these products be spearheaded and developed by ONI a minimum of once a month, no more than an hour in length, and hung in a low-bandwidth form on the Secret Internet Protocol Router (SIPR) Network; SIPR has to be the medium of choice to reach the greatest audience, afloat or ashore. Audio versions of the same briefs can be posted to the web for bandwidth constrained platforms and units, and the corresponding visual aids can be included in downloadable zip-files. Additionally, distributing an annual DVD compilation of the briefs to all Navy units would enable periodic training regardless of connectivity or bandwidth.

Challenge 2: Emphasis on Bridging the Operations and Intelligence Divide

There is a wealth of evidence—albeit mainly anecdotal—pointing to a persistent need to strengthen communication and trust between Unrestricted Line (URL) Officers and Intelligence Officers. To support operations effectively, the Navy IC must develop a better understanding of at-sea expeditionary warfare operations, operational terminology and practices, and the challenges that operators face. Similarly, to effectively consume and synthesize intelligence products, warfighters and planners must understand the cyclic relationship between intelligence and operations. Knowing what the Navy IC can provide, how missions and operations feed intelligence assessments, and how to frame questions effectively will ultimately improve productivity and the quality of naval intelligence professionals and operators alike. Ironically, the IC typically understands the capabilities and limitations of foreign forces well, but we can do a better job understanding those of our own fleet.

Junior URL Officers typically have limited cross-community learning and familiarization due to their respective warfare qualification processes and job requirements.2 These early years are exactly when junior officers need to begin learning about other communities, so they can foster the trust that is critical in the operations and intelligence relationship. The foundation of these relationships lies in an appreciation for one another’s work and an understanding of the interrelatedness of each community. The IC must accept responsibility for educating naval warfighters on our community while educating ourselves on theirs. Increased alignment will enable operators to understand the right questions to ask, thereby allowing intelligence professionals to provide improved time-sensitive, succinct, and relevant intelligence to our fleet.

Solution: Identify and Employ Cross Community Engagement Opportunities

A primary focus of an Intelligence Officer’s first tour is the completion of their professional qualifications—a process that can take up a majority of their time. Our first proposal is placing emphasis on getting our 1830s qualified as quickly as possible and then using the remaining time in their initial tour to embark a variety of ships and submarines; the benefits are three-fold.

Foremost, it will broaden the young officers’ knowledge of our fleet including the hardware, technology, and terminology associated with conducting at-sea operations. Second, it will allow them to receive valuable training from peers working across the operational spectrum. Lastly, it will foster side-by-side communication and cohesion with URL peers. Part of this initiative might include NIOBC students completing their initial Personnel Qualification Standards (PQS) before graduation, thus speeding their Information Warfare (IW) qualification process upon entering the fleet.

The second proposal is integrating intelligence familiarization into the training pipelines for URL Officers. This familiarization would occur primarily aboard big-deck amphibs and carriers, where officers can receive in-depth tours and briefs on the routine operations and capabilities of strike group intelligence centers. The training will demonstrate the value intelligence teams provide, how to communicate with them, their limitations, and how URL Officers contribute to Indications and Warning (I&W). In the case of Surface Warfare Officers (SWOs), this could become a small portion of the Basic Division Officer Course (BDOC) already being taught.3 An alternative and complimentary approach to address existing apprehension between Operations and Intelligence is to increase the number of lateral transfer URL Officers in the 1830 accession model. A third prospect is expanding the SWO-Intel option at all accession sources so a larger number of future Intelligence Officers will have completed initial URL tours aboard surface warships, thus developing familiarization and relationships with other communities.

These suggestions alone will not break down all barriers and communication challenges between Ops and Intel. However, when coupled with frequent engagement opportunities, familiarization with new intelligence practices, and manning and accession changes, increased trust and cohesion amongst our Fleet’s cadre will flourish.

Challenge 3: Improve Awareness of International Maritime Security Organizations, Shared Lines of Effort, and Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) Developments

The CNO has charged our Navy with expanding and strengthening our network of interagency and international partners. Maritime security organizations across the world possess valuable knowledge, tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP), along with lessons learned regarding their experiences with MDA and maritime security threats. It is imperative that we expose our Intelligence Officers to these organizations, their practices, processes, and ideas. Collaboration and novel lines of communication with these agencies will help enable the global information-sharing network required for the coming decades. However, to get there, these partners must believe we understand their concerns, modi operandi, and capabilities, and they must trust their USN counterparts.

Many partner navies align closely with U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) missions, an area where the U.S. Navy lacks proficiency. We can improve relationships with those navies by working together, understanding their challenges and perceived threats—even if they are atypical for our fleet. An example of this is Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated fishing (IUU), which is the scourge of developing maritime nations the world over, but garners little attention from the USN.

We can enhance our international relationships and improve information sharing by familiarizing ourselves with maritime threats like this, enabling more effective management of lines of communication. Understanding our international partners’ concerns will make us a more effective partner, paving the way for cooperation and trust across a range of issues.

Solution: Engage with Local and Foreign Maritime Security Organizations

Identify organizations that practice the key principles of MDA and information sharing, like major CONUS and OCONUS port operations control centers, USCG and Department of Homeland Security Interagency Operations Centers, and multi-national coordination centers like those in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Lisbon, Cameroon, and Northwood.4 Send groups of mid-career Intelligence Officers on periodic familiarization trips to these destinations for engagement and collaborative discussions on current trends, threats, and lessons learned from combating maritime security threats.

The USN target audience will be Lieutenant Commanders (O-4s); the goal would be to—at least once a year—send a small group of personnel from various commands to spend 2-4 weeks touring these sites. Their mission would be to receive briefs on their hosts’ missions and capabilities, and provide reciprocal briefs on information sharing and maintaining MDA. This would potentially look like a scaled-down version of the initial familiarization training that a Foreign Area Officer (FAO) receives.

The overall goal of this initiative is to broaden our connection to the greater MDA and maritime information sharing communities, establish and maintain relationships and working lines of communication. Participation in these visits can be tailored to inform the Navy IC through end-of-mission briefs to leadership at ONI, Combatant Command (COCOM) JIOCs, and numbered fleets. Longer-term opportunities exist in the form of International Liaison Officer posts at foreign maritime security centers. These liaison billets foster greater understanding of international and regional maritime security trends and the capabilities and limitations of global partners. Similar to the SECNAVs Tours with Industry program that affords military members an opportunity to work with large civilian corporations for a year; this international exchange program will expose officers to new ideas and organizations, fostering relationships, information sharing, and improving MDA.

Conclusion

The Navy Intelligence Community has played a vital role in our Fleet’s success from Midway through the Global War on Terrorism. To continue this effort, the Navy IC must demonstrate initiative and creativity to address the challenges identified by the CNO. Usable and timely intelligence must be communicated across the fleet to decision-makers and warfighters in all phases of operation. To effect these activities, new technologies will be used, new domestic and international relationships will be required, and an increased level of coordination and trust must be fostered amongst Intelligence and Operations professionals.

Cross-community trust and engagement will enable improvements in all parts of the intelligence cycle, better preparing our Fleet for the warfighting environments of the 21st century. Navy IC-led international partnerships and information sharing will provide new levels of access to intelligence, facilities, and new technology in this era of increased globalization. These changes will not happen immediately, they will require adaptation, ingenuity and a cultural shift. This is an opportunity and challenge we are ready to accept.

LT Millard Bowen is a former Surface Warfare Officer and was most recently the N2 for COMDESRON SEVEN in Singapore. He is currently serving as the Operations Officer for NCIS’s Multiple Threat Alert Center (MTAC). He can be reached at [email protected].

LT David M. Andre is a former Intelligence Specialist, and has served as an Intelligence Officer and Liaison Officer assigned to AFRICOM. He is currently serving as N2 for COMDESRON SEVEN in Singapore. He can be reached at [email protected].

The views expressed above are the authors’ alone and do not reflect the official views and are not endorsed by the United States Navy, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or any other body of the United States Government.

Endnotes

1. An additional benefit to this approach is the Navy’s younger generation of Officers and Enlisted will likely be more receptive to multi-media training tools like these.

2. This is more common in the Surface Warfare and Submarine communities. Aviation Squadrons and Naval Special Warfare units have assigned Intelligence teams, so there is more familiarity earlier in their careers with varying degrees of success.

3. There may be opportunities for similar Intelligence familiarization training in the initial training pipelines for Naval Special Warfare, Aviators and Submariners, but future collaboration with those communities will be required to identify when and how best to integrate these topics.

4. Singapore hosts the Information Fusion Centre (IFC), Kuala Lumpur hosts the International Maritime Bureau Piracy Reporting Centre (IMB PRC), Lisbon hosts the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA) and the Maritime Analysis and Operations Centre – Narcotic (MAOC-N), Cameroon hosts the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Inter-regional Coordinating Center (ICC), Northwood, England hosts the NATO Maritime Command HQ, the NATO Shipping Centre (NSC) and the Maritime Security Center – Horn of Africa (MSCHOA).

Featured Image: Two U.S. Navy Sailors and Peruvian sailor confirm position of simulated enemy destroyer in combat information center aboard guided-missile frigate USS Rentz during wargames as part of annual UNITAS multinational maritime exercise, off coast of Colombia, September 14, 2013 (U.S. Navy/Corey Barker)

Featured Image: Two U.S. Navy Sailors and Peruvian sailor confirm position of simulated enemy destroyer in combat information center aboard guided-missile frigate USS Rentz during wargames as part of annual UNITAS multinational maritime exercise, off coast of Colombia, September 14, 2013 (U.S. Navy/Corey Barker)