By Matthew Hipple

“About 300 ships, achieved in FY2018, will provide a force capable of… assuring access in any theater of operations, even in the face of new anti-access/area-denial strategies and technologies.” —Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels, June 2014

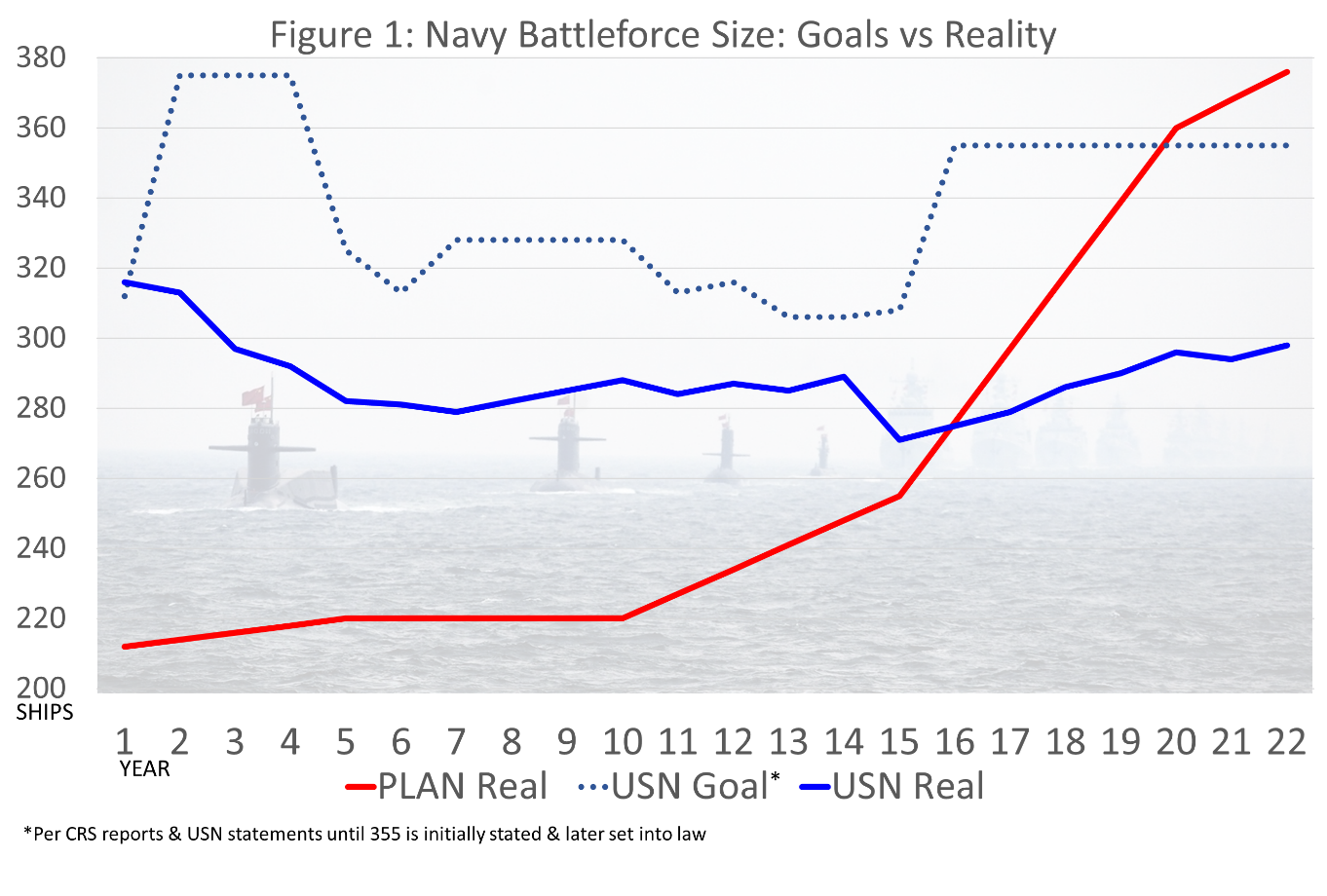

In 2014, before the scale of Chinese naval development was widely appreciated, the Navy reported to Congress a Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 near-term requirement of 300 ships for “conducting a large-scale naval campaign in one region while denying the objectives of an opportunistic aggressor in a second region.” In the time since, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) added more than 120 battleforce ships and countless maritime militia – while the U.S. Navy still remains short of the lapsed 300-ship goal, and 57 ships short of its current 355 ship requirement. In the past 20 years the Navy’s ideal battleforce goals have all exceeded 306, but the fleet has not broken 300 ships since 2003 (Figure 1).

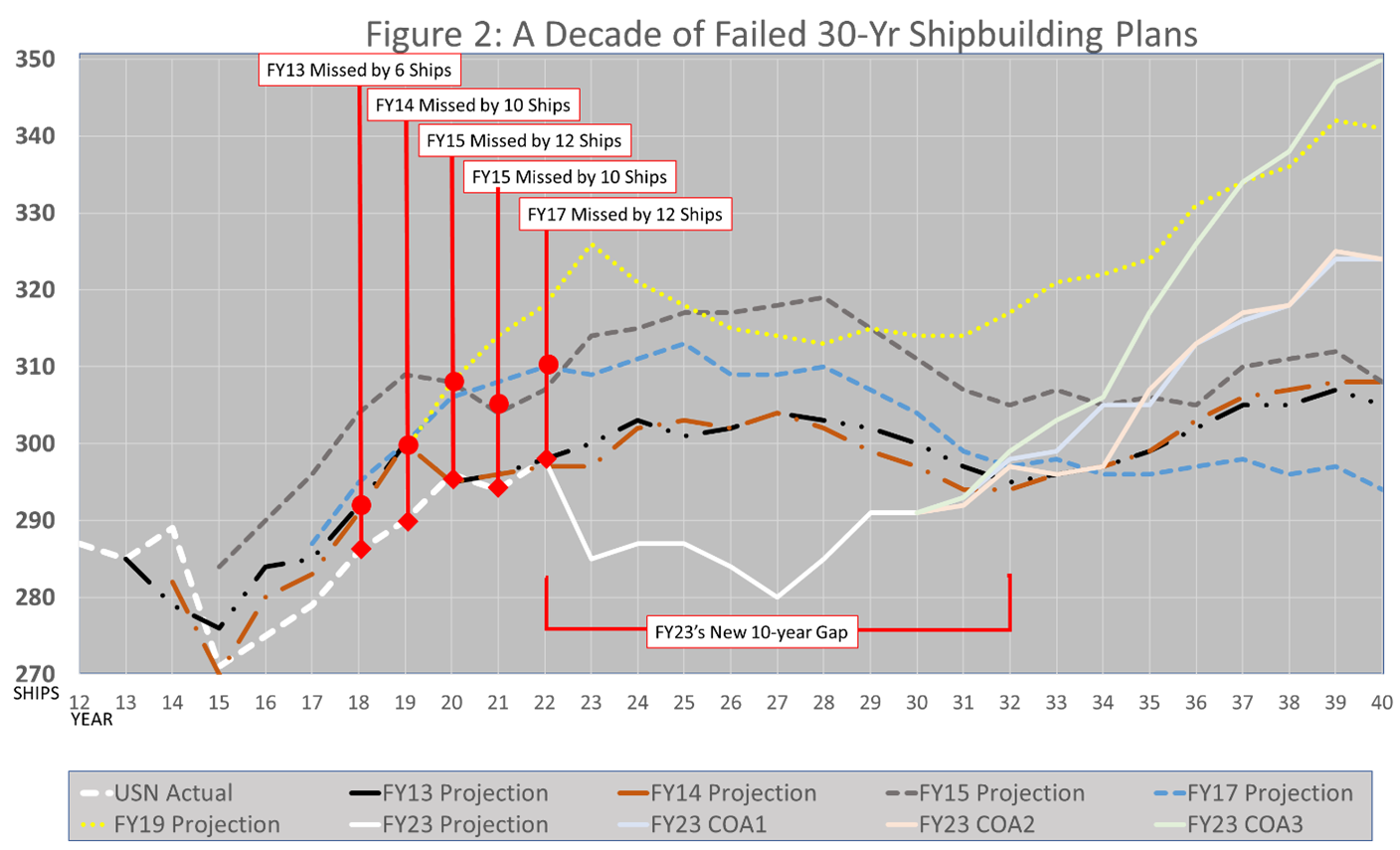

Though glaring, the fleet’s numerical crisis is merely a symptom of the Navy’s 20-year institutional inability to overcome the pressures driving down fleet numbers and ship production. The nature of the financial, material, programmatic, institutional, historical, and political pressures suppressing fleet growth are up for debate – but the extrapolated results of these downward pressures are not, as seen in the Navy’s failure to meet the various Shipbuilding Plans. However, those missed shipbuilding plans also represent the Navy’s resistance to the significant pressures that would degrade or trade away the fleet.

Since 2016, even enshrining the 355-ship fleet in law only produced a net battleforce increase of 19 ships over seven years, a rate by which the Navy would gradually reach 355 ships by 2041. Unfortunately, the FY23 Shipbuilding Plan eliminates what upward pressure contributes to a modest improvement in fleet size trajectory. The FY23 Shipbuilding Plan proposes a 10-year drop in fleet numbers that deviates in spirit from every shipbuilding plan since 2012. During this dangerous decade, the FY23 Shipbuilding Plan returns the fleet to a size that precipitated the period of panic that inspired Congress to enshrine the 355-ship goal into law (Figure 2). The FY23 Long Range Shipbuilding Plan will miss the defunct, minimum goal of 300 ships by another decade, and is less likely to meet the Navy’s legal and operational 355-ship requirement

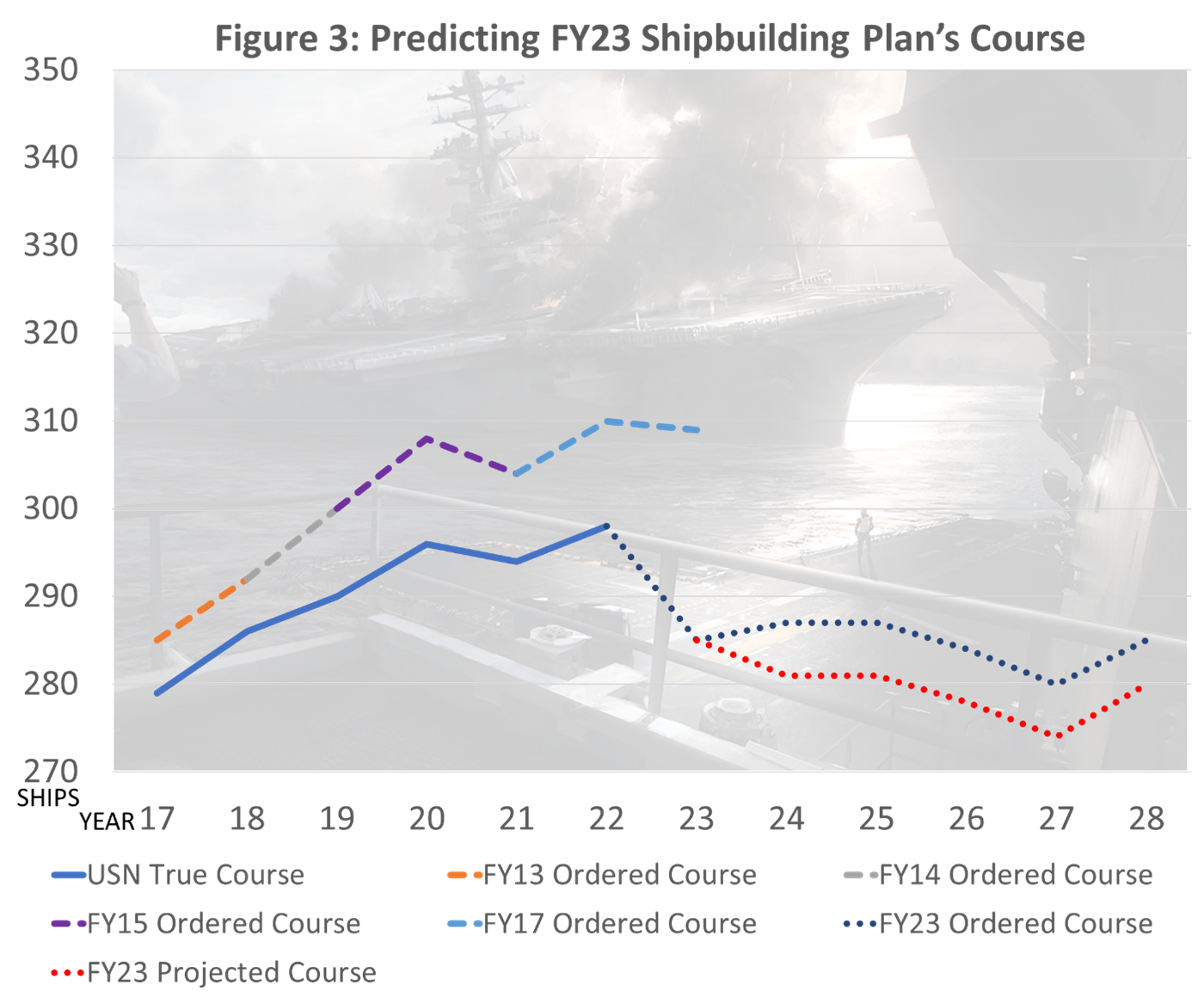

The FY23 Shipbuilding Plan’s change in course is doubly precarious as its dangerous decade fleet reduction also embraces the downward pressures the shipbuilding plans struggled to resist. This resistance is comparable to the navigational concept of “crabbing” – where a ship is driven at odd angles up a channel to resist currents driving it into danger. The Navy, with the wheel hard over to increase the size of the fleet, had only achieved marginal success. Driving with that downward current into a fleet reduction would be disastrous, and likely drive fleet numbers lower than anticipated.

In an attempt to assess the downward current and potential results of the reduction, we must assess the difference between the Navy’s ordered and true course for fleet size. As with a large ship, the Navy can take time to respond to rudder orders – so we extrapolate the impact of shipbuilding plans by looking to their effects five years in the future. The average gap between ordered and achieved battlefleet size over the last five years was roughly 10 ships. Integrating the precipitous drop from 2022 to 2023 and loosely projecting that magnitude of 50 ships over five years shows a battleforce of 275 ships or smaller (Figure 3).

During a decade that many U.S. Department of Defense leaders have characterized as particularly dangerous for deterrence of China, the conventional PLAN may outnumber the total USN by 50 percent. The United States nor its Navy would fight China alone – but the rapidly worsening margins remain a concern. The majority of U.S. allies in the region fall well within the PLA/N/AF’s collective weapons engagement zone, the PLAN retains significant mining stockpiles alongside fielding a vast maritime militia, and the PLAN benefits its regional focus with even greater numerical superiority compared to U.S. warships immediately present in WESTPAC. That the Navy has struggled to improve fleet growth in the face of such grave circumstances bode poorly for a post-FY23-reduction recovery.

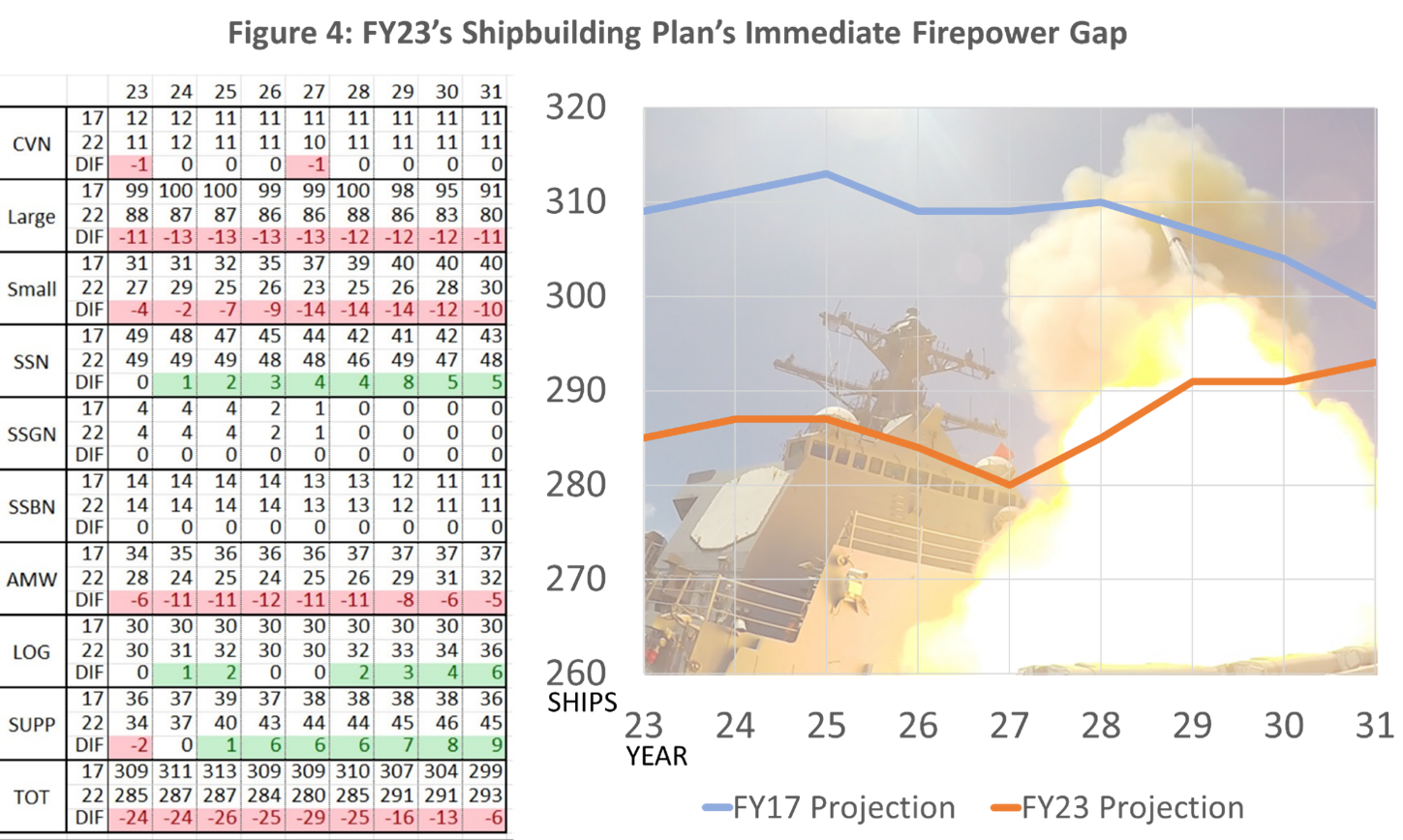

Further, buried within the FY23 capacity gap is a lethality gap. To avoid the appearance of unfairness in comparison, we look at the FY17 Shipbuilding Plan which represents a conservative mid-point between the Obama and Trump administrations’ more robust FY15 and FY19 shipbuilding plans (Figure 4). Before the FY23 Shipbuilding Plan’s proposed courses of action begin to significantly deviate in 2032, battleforce shortages are primarily restored by support and logistics ships, with a smaller number of attack submarines. The strategic decision to shift resources to the long-neglected logistical tail is sound. Nonetheless, failing to fix cruiser modernization or increase production leaves this better-supported fleet gapped by a number of surface combatants that is roughly the equivalent of the forward deployed 7th Fleet at a time when the PLAN will exceed a battleforce of 420 ships.

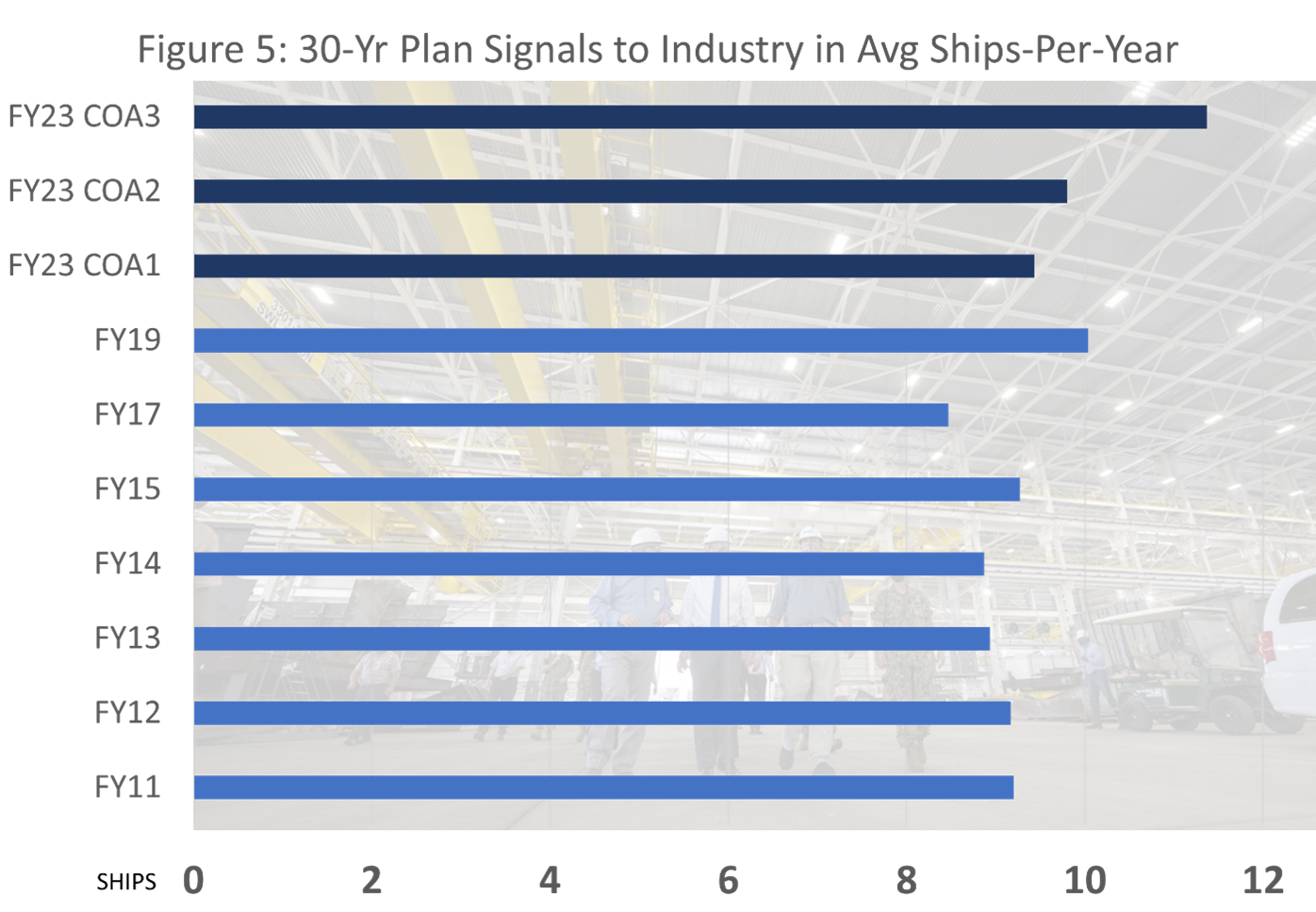

Though the FY23 Shipbuilding Plan anticipates recovery in the early 2030’s, the signal to industry is an average ships-per-year rate lower than the FY19 Shipbuilding Plan and only marginally higher than the past decade of plans (Figure 5). Given the immediate downward trajectory planned by the Navy and the Navy’s track record of falling short of its plans, shipbuilders may be reticent to make the major capital and labor investments necessary to sustain the current industrial base, much less expand and modernize it.

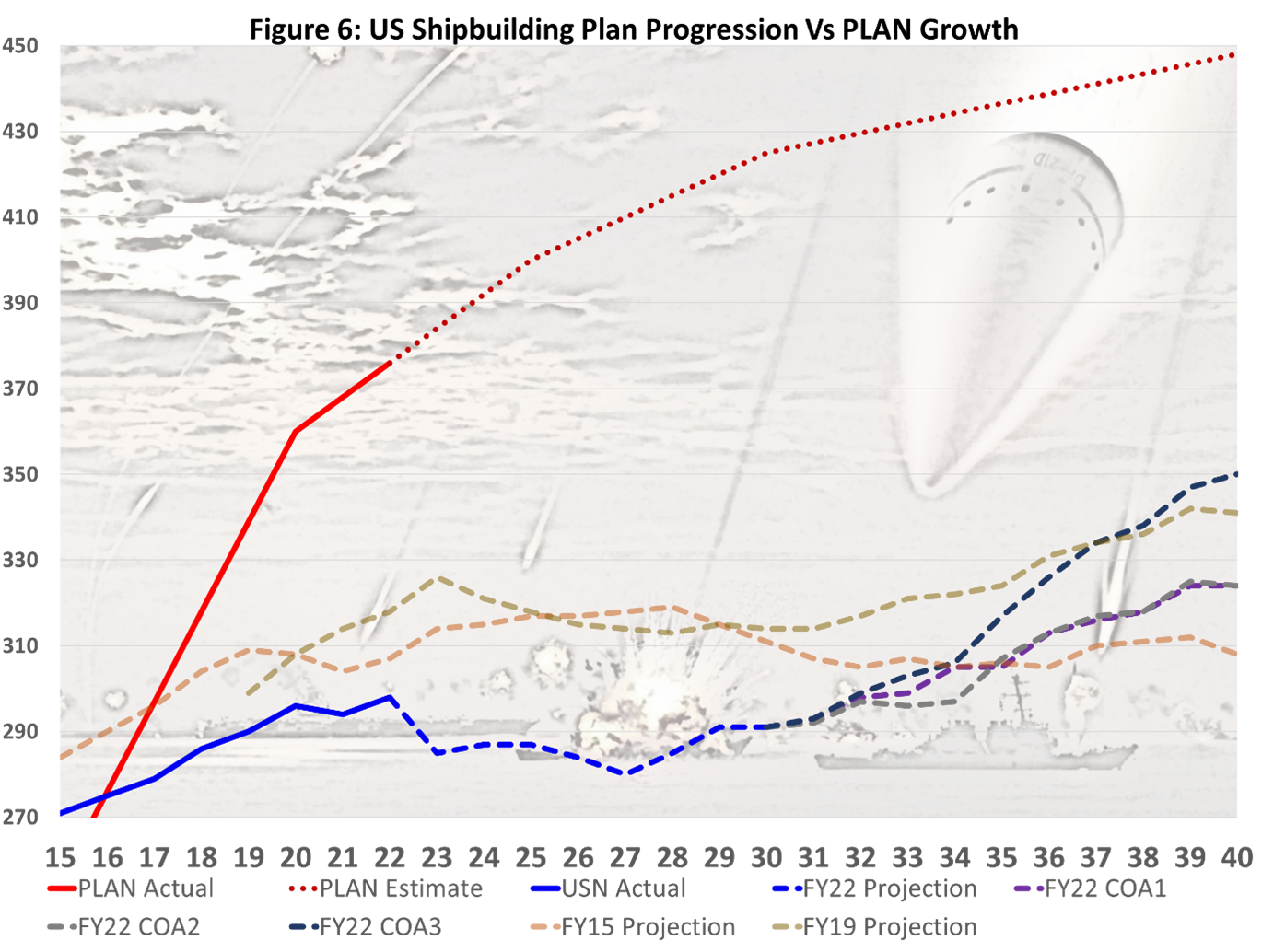

Previously, the Navy’s shipbuilding plans made evolutionary progress (Figure 6). The Obama administration’s post-sequestration FY15 plan appropriately departed from the FY13/14 plans by increasing the fleet’s status-quo, pushing for a de-facto baseline of 310 ships. As the threat of the PLAN evolved and long-awaited silver-bullet technologies did not appear, the Trump administration’s FY19 plan replaced previous plans’ period of stability from 2031-40 with a fleet increase. In retrospect, both plans failed – but both plans applied necessary upward pressure and both ensured a minimum fleet size was retained. The FY23 plan will kill that pressure – and must be revised to improve on FY15 and FY19’s positive movement rather than embrace the false promises of divesting capacity today to gamble on solutions a decade or more away.

While the FY23 shipbuilding plan accepts a third gapped decade, the PLAN’s size, skill, and industrial base will continue to grow. With global commitments and the tyranny of distance, the United States faces a Port Arthur problem with being able to respond to the CCP’s maritime behemoth much like a split Russian fleet was defeated by Imperial Japan’s modernized and regionally-focused Navy. We must provide serious focus to the lagging Pacific Defense Initiative while the USN maximizes its efforts to retain working warships until replacements come online and the supporting maritime industries sufficiently expand. In developing replacements, the Navy must make clear commitments that signal to industry a sea change in ship demand that will justify the intensive investment needed for new and/or expanded shipyards, like the Lordstown-Lorain project – if not pursue new yards of the Navy’s own.

The time has passed for the resets and divestments of the past revisited by the FY23 shipbuilding plan. The currents ahead are strong, and the Navy must resist them rather than be driven up onto the shoals. Decline is a choice we must resist.

Matthew Hipple is an active duty naval officer and former President of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC).

Featured Image: The U.S. Navy guided missile destroyer USS Ramage (DDG-61) in a floating dry dock at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Virginia (USA), on 25 May 2012. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)