Flotilla Tactical Notes Series

By Charles “Chip” Swicker

The CO sets the standard. He or she must make it clear that the first priority is combat readiness. Every CO must choose the level of “creative drama” with which they are comfortable, and how they project this priority to the crew. I did every awards ceremony and every captain’s call wearing my pistols. That worked for me, it might not for everyone. The crew must believe it, and you must believe it, too. They must believe that you genuinely care about combat readiness first and foremost, and that your visage as a combat-ready commander will translate into tangible action for preparing the crew.

Full battle dress is the uniform in which American Sailors will fight their ship. The CO should formally inspect every division in full battle dress (including helmets, body armor, etc.) during division in the spotlight. As CO on McCAIN and VICKSBURG, I would not inspect my crew in any other uniform. XO and CMC did all dress uniform inspections. No matter what material condition you chose to fight your ship in, make sure your crew fights and trains in full battle dress.

Take the time and spend the money to outfit them like the lethal professionals they are:

- Fresh, clean flashgear, stenciled by name and replaced regularly.

- Helmets painted, stenciled, properly fitted and padded, with working 3-point harnesses.

- Ballistic eye protection for any Sailor manning or carrying a weapon.

- Body armor for all hands topside in Condition 1, all SCAT, all Bridge Team. It must fit, it must be clean and stenciled, it must look uniform. (All the body armor in McCAIN and VICKBURG was rehabbed, fitted properly, and then made uniform with a careful application of haze gray paint.)

When a team trains like a team and looks like a team, the energy really resonates with Sailors. Combat is a team sport. Train your Sailors with a stopwatch, and coach them toward a goal of flawless execution at speed. Train them day or night, rested or tired, so that their muscle memory carries them through in the confusion and terror of an actual sea fight.

Review your watchbills carefully. I fought old-school, from Condition 1. If a CO decides to fight from any other condition of readiness, look carefully at that watchbill for any location where a Sailor might be stationed alone in combat conditions. Fix that. Young men and women in combat fight for each other, and that dynamic keeps their courage up and their attention focused on the vital tasks with which they are charged. Have a minimum of two Sailors at any given watch station. Leave no one alone in a fight.

During lulls in engagements, a pair of designated CPOs or a CPO and a JO should make the rounds with a coaling bag full of bottled water and Red Bulls (and perhaps some high calorie geedunk). This “Roving Morale Check” should look every Sailor in the eye, give him or her a handshake and a thump on the back, hand out a drink or a snack from the coaling bag, and make sure that Sailor is never out of the fight. This also gives the team a chance to spot minor or major injuries and damage that was not reported on the net. This technique was combat proven by the Brits in the Falklands War.

Whenever SCAT is called away, Igloo coolers of fresh water go with them to every gunmount. When Sailors are wearing full battle dress, body armor, and helmets while running .50cals as fast as they can load the belts, they will lose pounds of water weight during every drill or engagement. Keeping your people well-fed and hydrated keeps them alert and aggressive. Beware of some bodybuilding supplements popular with Sailors, such as creatine and Hydroxycut. I forbade their use by my VBSS teams because of their dehydrating effect. Get HMC and the Baby Docs involved in getting the word out.

During Full Mission Profile battle problems and ship survivability exercises, build up gradually to the point where the training teams can “kill off” significant numbers of Sailors and officers. Have the Corpsmen break out the moulage gear on a regular basis, and make sure your designated victims scream their lungs out. Properly done, the effect is horrific, and can make your eyes sweat as you watch the pilothouse, the combat information center, or other space reduced to a mass of bodies. Sailors arriving on a simulated casualty scene must remove body armor and helmets from their shipmates, stack the gear neatly or don it themselves, and then must physically carry their “dead” shipmates out onto the signal bridge or other clear space to clear the bridge for the surviving/relieving watchstanders. Leave one junior officer standing to take charge and call for help (and steer the ship if you kill the bridge team).

When this exercise is done with safe supervision and utter commitment to realism, the effect on Sailors is stunning. It really recasts their attitude about the nature of combat at sea. It also sets the stage for a very useful captain’s call immediately afterward and talking honestly with the CO, XO, and CMC about their chosen profession. My crews from McCAIN and VICKSBURG remember those talks to this day.

The CO must hold regular mentoring sessions with his or her wardroom on the nature of combat and combat leadership. Commodore Mike Mahon brought me and the other DESRON 15 COs up to his office in Yokosuka to watch the scene from the movie “Glory” where Colonel Shaw fires his Colt revolver next to the head of an enlisted man, imploring him to load faster. The Colonel had survived the carnage of Antietam and knew the importance of training his men “properly.” That was the Commodore’s way of announcing to his COs that combat readiness was indeed his first priority, and that we ignored this fact at our personal and professional peril.

Your key demographic is young Americans aged 18-22 with a high school education. You must pitch and connect at this level. Walk about and talk to your Sailors every day. Tell them why they are vital to your efforts on behalf of the Navy and the nation.

If the CO publishes a command philosophy, it must emphasize combat readiness and actually resonate with the demographic of young Sailors. In two commands, I had great success with only seven words:

Sail Fast.

Shoot Straight.

Speak the Truth!

Retired Navy Captain Chip Swicker is the Senior Mentor for the Navy’s Integrated Air and Missile Defense Warfare Tactics Instructor Program. He served as Electrical Officer and Navigator in USS Scott (DDG 995), Fire Control Officer and Battery Control Officer in USS Virginia (CGN 38), Weapons Officer and Combat Systems Officer in USS Philippine Sea (CG 58) and Executive Officer in USS Monterey (CG 61). His sea duty culminated as Commanding Officer of the Aegis destroyer USS John S. McCain (DDG 56) and the Aegis cruiser USS Vicksburg (CG 69). Captain Swicker received a Master’s degree in Scientific and Technical Intelligence from the Naval Postgraduate School in 1990. From September 2003 to November 2005, Captain Swicker was director of the Command at Sea Department at the Surface Warfare Officers School in Newport, R.I. From January 2008 to December 2010, he was Chief of the Special Actions Division on the Joint Staff. He retired after 30 years on active duty in 2012.

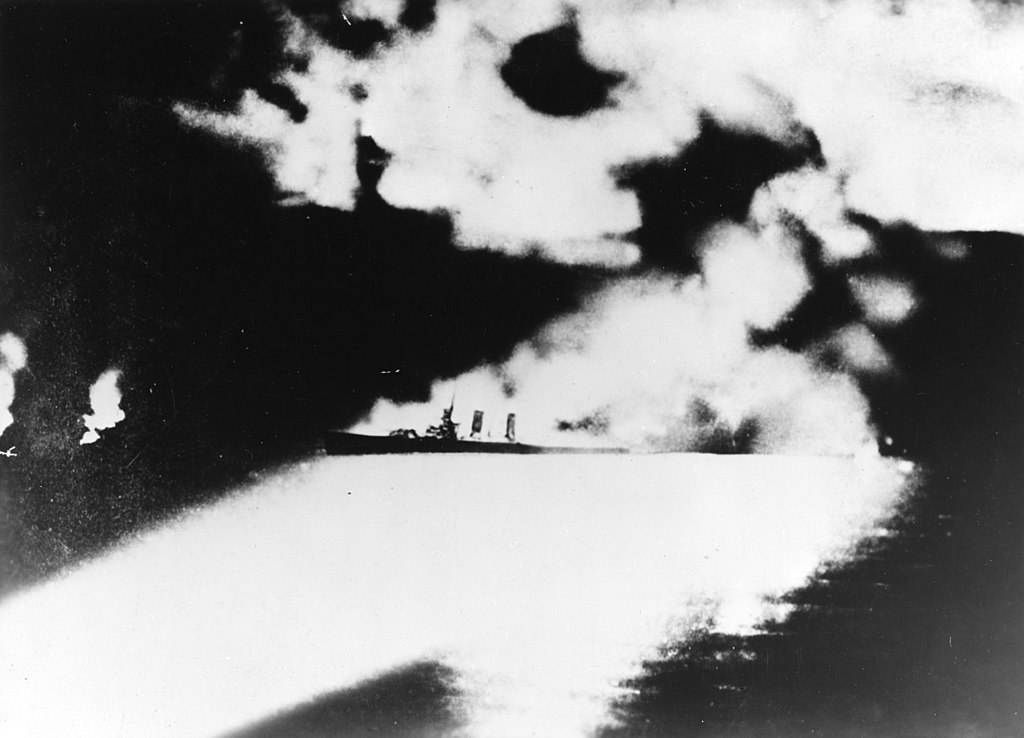

Featured Image: SOUTH CHINA SEA (Oct. 7, 2020) – Fire Controlman 2nd Class Samuel Thomas, from Carol Stream, Ill., ‘racks’ an M2HB .50-caliber machine gun on the foc’s’le during a small craft attack team (SCAT) drill aboard the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS John S. McCain (DDG 56). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Markus Castaneda)