By Stephen M. Carmel

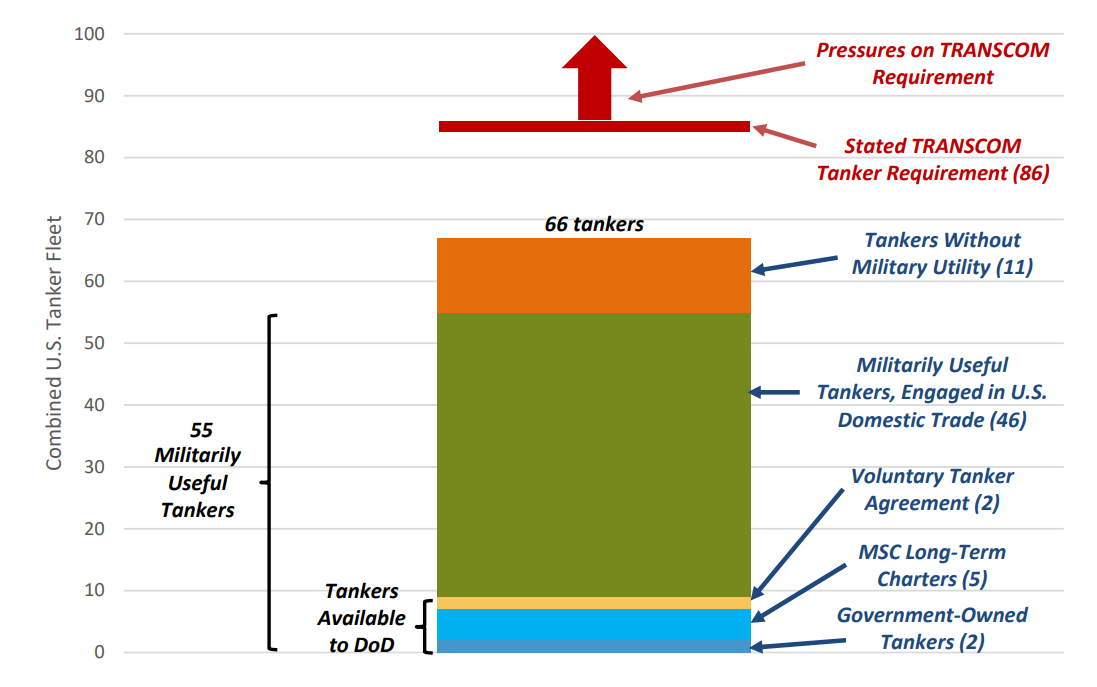

The Department of Defense is projected to need on the order of one hundred tankers of various sizes in the event of a serious conflict in the Pacific.1 The DoD currently has access it can count on – assured access – to less than ten. Not only does the U.S. lack the tonnage required to support a major conflict in the Pacific, it has no identifiable roadmap to obtain it. Without enough fuel, the most advanced capabilities and ships – even nuclear-powered aircraft carriers – will hardly be available for use. This is a crisis in capability that requires urgent and effective action. There is little time to get a solution in place if speculation that conflict with China could happen this decade proves true. Thankfully, this is a problem that can have a timely and affordable solution. However, the U.S. needs to move past conventional thinking and long-established policies that brought us to this current state.

To Win the Fight Requires Fuel

In the event of a broad conflict with China in the Pacific theater, the U.S. will likely lose reliable access to the currently relied-upon sources of oil within the region. The U.S. will then need to manage exceedingly long lines of supply to ensure oil flows to the forces in the greatly increased quantities demanded by a wartime operational tempo. But it must be remembered that there will be many other consumers of oil competing for those same barrels in a highly disrupted oil market. The cascading effects on the totality of the oil system, from production to distribution across all users, must be hedged against. The Defense Production Act does not apply to foreign refineries and the U.S. government cannot compel where these foreign-produced barrels go. Refiners must not only have the oil to sell, but be willing to sell it to the U.S. military in the midst of what may be a politically controversial war. This access should not be taken for granted, especially given China’s deep reach and increasing influence over the international oil market, the developing world, and the associated energy infrastructure.

The long supply chains for delivering wartime energy from North American sources to the Pacific theater of operations would require a large number of tanker ships. In thinking through the tanker requirement, one must also factor in some level of attrition in lost ships and crews due to combat action, especially when a prudent adversary would prioritize attacking these critical enablers of U.S. power projection. Attrition and escort requirements must be accounted for in planning. Balancing operational logistical demands in the face of attrition and the evolving availability of tankers is a dynamic planning challenge. It requires steady effort throughout the duration of a conflict that features rapidly changing oil supply points and platform availability.

The U.S. would need several different types of tankers to address these challenging scenarios. Larger tankers are needed to do the long-haul parts of the distribution process. These would be principally MR, or “Medium Range” tankers which are the ideal size for the Defense Department and would be needed in large numbers. These are ships that carry roughly 330,000 bbls of multiple types of refined product. They can be fitted with consolidated cargo replenishment (CONSOL) gear to conduct at-sea refueling of oilers which will then refuel the fleet. This capability is currently available on a few MR tankers on charter with the Military Sealift Command. But current CONSOL operations are short-duration exercises and have not been done under contingency conditions in many years. The other type of tanker needed would be smaller, shallow-draft ships in the 40,000 bbl range for intra-theater lift. These smaller tankers would be used to provide fuel to distributed forces across the Pacific.

The current crisis in tanker capability, combined with a high optempo conflict, could result in the distinct possibility that U.S. forces run out of fuel. Sufficient tanker capacity is indispensable to wartime success and must form a central consideration in planning. Current Defense Department planning embodies inherent assumptions about assured access versus assumed access of supply. As the National Defense Transportation Association describes it:

“If the U.S. adopted an assured access approach, it would be comprised of U.S. Flagged ships owned by U.S. companies and crewed by U.S. citizen mariners—somewhat similar to the Chinese strategy (which applies to the entire nation of China, not just their military).The assumed access approach relies on the outsourcing delivery of fuel to the military in times of conflict—with limited description regarding the private parties involved and the extent which access to product would be guaranteed. Working out these details will come at the start of conflict, when demand signals surface for fuel requirements. The assumed access approach relies on the concept that the international tanker market is large compared to the U.S. military demand in a peer to peer full scale conflict.”

Military logistics planners lean toward assumed access, that tankers will be available from foreign-flagged tonnage. This assumption betrays a lack of understanding of the international tanker market and the significant influence China now has over it, including the often-overlooked issue of actual ownership, which is not the same as flag or company. In fact, a substantial portion of European tanker fleets, flying flags normally considered non-hostile to U.S. interests, are actually owned by Chinese financial houses through sale lease back-arrangements.

Assumed access also does not address the very dynamic aspects of the tanker market and the dramatic effects current events can have on availability. The current situation affecting the global tanker markets – tight supply accompanied by high charter rates – is driven by the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. But this is but one example. A conflict with China may have even more dramatic consequences for the markets. There will be significant but unpredictable impacts on oil markets, tanker markets, and trade flows upon which to base assumptions on tanker availability. Assumed access also means assuming tanker companies and their stockholders will value the U.S. military, with whom they may have no relationship, over their commercial interests with whom they have longstanding relationships.

Tanker companies, not countries, ultimately own the ships and it is commercial companies that must choose a side. Part of that decision will be based on their assessment on who will “win” in the conflict. Picking the U.S. is currently far from a safe bet, at least in the eyes of international companies that will still want to preserve their commercial relationships, largely oriented toward Asia, when the conflict is over.

Assured Access Solutions

Assured assess means the U.S. Navy or U.S. flag shipping companies own and control the ships outright. Availability is not premised on assumptions or expectations about external actors and their assets.

Assured access still comes with challenges to tanker availability. The tanker problem must be solved as a system that considers labor requirements and the demands for sustaining economies amidst a systemically disruptive conflict. Tankers require different credentials from dry cargo vessels and a container-ship officer is only qualified to sail tankers if they have the requisite endorsements which can only come from sailing on tankers. In addition, the domestic oil markets which fuel the U.S. economy must remain functional. There will also be heavy demand for tonnage to service allied economies impacted by the distortions in energy flows.

A current legislative effort to address this problem is the proposed Tanker Security Program (TSP), which provides a stipend to firms that flag tankers into U.S. flag for international trade. The program is limited to ten ships due to the amount of annual funding authorized and appropriated for stipends. This program is flawed however, in that the stipend is too small for enrolled vessels to remain commercially viable for trading in normal markets. (The current tanker market, with historically high charter rates, is not considered “normal.”) Instead, the program allows double dipping so ships can be on short-term charter to the U.S. government carrying preference cargo while still collecting a stipend. Because there are already ships under U.S. flag on short-term charter to the government, the TSP vessels will simply replace these existing vessels, collecting a windfall but adding no new capacity. The program is also not scalable, and even if all other elements work as intended, it could not produce anywhere near the needed number of ships for a major wartime contingency. The program has also yet to address other issues, such as ensuring the vessels have the necessary capability and compatibility with their intended use by the U.S. military in time of conflict. As an example, the program has not determined whether CONSOL equipment and CONSOL-trained crews will be required on these ships, creating uncertainty on funding for this capability, which then creates uncertainty within industry on the financial aspects of the decision to bid for TSP slots.

It is clear that the TSP will not solve the overall tanker shortage. A comprehensive tanker solution that is affordable and can grow the fleet at scale would necessarily consist of a combination of several different programs. First, the TSP must be revised to provide a stipend large enough to allow for commercial trading of U.S. flag tankers in the international market with no reliance on U.S. flag military (preference) cargo. In fact, carriage of preference cargo for TSP ships should only be allowed during times of national emergency. Otherwise, participating ships should be restricted to commercial work. This will produce a fleet of incremental U.S. flag tankers the Navy does not already have access to, with the scale of the program determined by the total amount of funding.

Legislation should be enacted requiring cargo preference on refined oil products being exported from the U.S. For reference, the U.S. currently exports 1.4 million bbls of refined product, principally to South America, every day, all on foreign flag tankers. The U.S. also exports a considerable amount of crude oil. While crude tankers are hardly militarily useful, their crews are useful by virtue of possessing the required documents and skills to sail tankers of any type. Therefore crude oil should also be a consideration. If cargo preference – the requirement that U.S.-flagged tankers carry a significant portion of this cargo – were in place, a substantial fleet of commercially viable but militarily useful tankers would be available as “assured access.” A significant benefit of this program would be that the cost of having that capacity available for wartime use is not borne by the U.S. taxpayer until it is actually needed. It is borne by the oil companies and the foreign buyers of the oil.

U.S. domestic sourcing of DoD fuel should also be put in place. The requirements of “Buy American” do not apply to fuel, and the Defense Logistics Agency Energy (DLA Energy) currently buys fuel wherever it is cheapest, normally meaning the closest source to the point of use. This is of course vastly different from the sourcing for so much else the DoD uses or procures, where “Buy American” applies. But those “point of use” sources of fuel for ships in the Pacific may be at risk in the event of conflict with China, assuming they are not owned or controlled by Chinese companies, which should not be overlooked.

As mentioned, the U.S. currently exports a large amount of refined product. Some of these exports could easily be diverted to DoD as a customer without heavily distorting the domestic oil market. It is highly likely some level of domestic sourcing would need to be done in a time of conflict. As a result, this program would put in place an oil supply chain that will be needed regardless, but in a phased approach that does not distort markets as opposed to an emergency program implemented in a time of crisis that is highly disruptive. Sourcing DoD oil domestically now will result in increased ton-mile demand, hence immediately increasing the need for tankers to carry it.

Lastly, the program run by the Military Sealift Command (MSC) for prepositioning refined product on tankers fitted for CONSOL should be put back in place. At one time, MSC had a large number of tankers under charter loaded with the types of fuel that would be needed in a conflict. These tankers were outfitted with all the required equipment for their military mission, were fully-crewed, and ready to respond immediately. This program, if revived, could be done quickly and supply immediate capability of the required type.

There are several points to consider when reviewing this menu of potential solutions. First, while some, such as adjusting the TSP, require congressional action which will take time, others can be done by DoD quickly. Prepositioning programs or DLA-E sourcing do not require congressional action and could be accomplished in shorter timeframes. Cargo preference for exports could potentially be done by executive order in the short term, but would certainly require congressional action in the longer term. But a central theme is that cargo must be at the center of any viable solution, not government stipends.

The above solutions must also be implemented in a phased approach to give labor and tanker markets time to adjust. The fact that we are presented with a mix of solutions, with some that can be implemented right away and others that require more time, is not necessarily a bad thing. The key point is that this must be implemented as a phased solution to a systemic problem. Stovepiped programs that do not mesh will not work. Given the very short overall timeframe available to implement a solution due to acute national security concerns with China, action must start now.

While the proper mix of the above will produce the required capability at an affordable price, it will not produce capability for free. All capability, from aircraft carriers to missiles, comes at a cost, as does the fuel that enables these capabilities. Fuel, and the capacity to deliver it when and where needed, must be placed on the same level of priority as other essential warfighting capabilities. These must be viewed as interim steps to ensure the tanker capability crisis is solved in a timeframe relevant to the near-term threat of a potential conflict with China.

Conclusion

The very fact that these types of programs need to be considered is indicative of decades of neglect in U.S. maritime strategy. The long-term solution must flow from a coherent national maritime strategy that addresses all elements of maritime power, not just naval power, and treats the maritime domain as an ecosystem that must be addressed holistically. The Chinese clearly have such a comprehensive maritime strategy, which is why China dominates the maritime domain when it is properly understood as encompassing all elements of maritime power. While the U.S. has what it terms a maritime strategy, it is in fact only a naval strategy that does not address the broader dimensions of maritime power. This needs to change, otherwise the U.S. may run the severe risk of neglecting critical elements of maritime power that China has been carefully cultivating.

Steve Carmel is Senior VP at Maersk Line Limited. He is a past member of the Naval Studies Board, the CNO Executive Panel, and Marine Board.

References

1. Timothy Walton, Ryan Boone, Harrison Schramm, “Sustaining the Fight: Resilient Maritime Logistics for a New Era,” Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, pg. 78, 2019, https://csbaonline.org/research/publications/sustaining-the-fight-resilient-maritime-logistics-for-a-new-era/publication/1.

Featured Image: ARABIAN GULF (May 5, 2016) – Fleet replenishment oiler USNS John Lenthall (T-AO-189) refuels the tanker Maersk Peary during a replenishment-at-sea. (U.S. Navy Combat Camera photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Joshua Scott/Released)