The following is a dissertation sample provided as part of Border Control week.

The case of American Prohibition is often deployed in the rancorous debates that surround counter-narcotics policy. Unfortunately, it is generally deployed (to my thought, abused) without an adequate understanding of what Prohibition actually looked like. This is especially true of rum-running, which is generally retold something along these lines:

Phase 1) Bill McCoy founds Rum Row.

Phase 2) ?

Phase 3) Repeal! (and rum smuggling magically ends.)

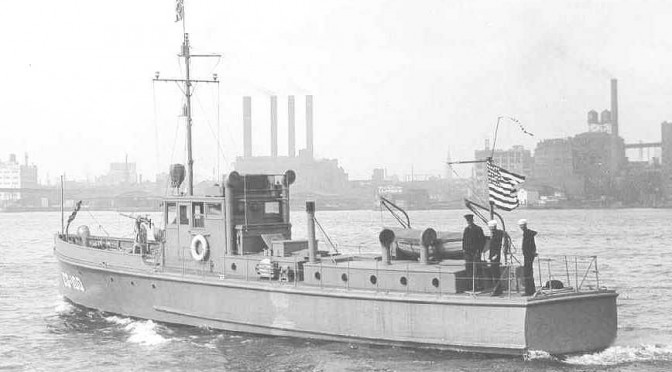

The actual Rum War at Sea was a story of two dueling adaptive networks. Until 1924, the Prohibition Bureau ran their own ‘Dry Navy’ of a handful of sub-chasers – this whole enterprise was entirely a disaster, due to poor personnel polices, wholly inadequate imagination, and total ineptitude at sea. In 1924, the Coast Guard (somewhat unhappily) took on the task. They managed to field a substantial, aggressive, and most importantly highly adaptive force built of everything from speedboats to destroyers. Within a few months, they shuttered Rum Row. Soon after, they chased the rum-running networks down to Florida (1925-1927) and then across to the Great Lakes (1928-1930.) The Coast Guard fought the remnants of the rum-fleet to a stalemate through the early thirties, even after their budgets were cut. The rum trade came back in force one year after repeal, and a recapitalized Coast Guard fleet ended organized alcohol smuggling in 1936.

In the course of this chase, Captain Charles Root founded US Coast Guard Intelligence, established HUMINT networks in Canada, Cuba, and a score of other rum ports, hired the legendary codebreaker Elisebeth Friedman, designed and fielded the first American SIGINT trawler. The Coast Guard chief engineer Hunnewell filled the coasts with two hundred patrol ships within less than a year, and then proceeded to reverse engineer the fastest of the rum-runners and field them too. Commandant Billard founded interagency and international task forces, which ultimately resulted in full tactical integration with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, including positive hand-offs and radio intelligence cross-cue. By the end of the case, the Coast Guard could fix a rum-runner by their radio transmission, send a patrol aircraft along the bearing line, visually acquire the craft and orbit overhead until the a boarding ship could make the intercept.

The Rum War built the Coast Guard, founded only a few years prior from the Revenue Cutter Service and the Lifesaving Service. It also advanced technologies critical to the Second World War – small craft (PT Boats – basically rum-runners with torpedoes, Higgins Boats – crewed by both Coastguardsmen and ex-rumrunners), codebreaking (Friedman’s USCG cell broke the Japanese merchant codes prior to the war) and radio direction finding. This case deserves more study, both as a maritime border control campaign, but also as a contest between two highly adaptive flat network. The Coast Guard achieved an enviable victory over bureaucracy at the outset, which allowed them to keep pace with their well-funded adversaries.

As a teaser, I submit the following account of the post-repeal suppression campaign, excerpted from my forthcoming dissertation.

I also include two animated infographics of capture records and intel reports, respectively. I hope that it will challenge standard conceptions of the Rum War, and entice the reader to read further. For further reading, I recommend the standard Coast Guard account, Rum War at Sea, by CDR Malcolm Willoughby.

All Captures GIS – Medium

New Animation – Medium

Repeal, 1933. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected on a platform that included the repeal of that act. He delivered on this promise in the early part of 1933 – the 18th Amendment prohibited ‘intoxicating liquors,’ while the Volstead Act defined ‘intoxicating liquors’ as anything 0.5% Alcohol by Volume. As the 21st Amendment worked its way through the system, the Cullen-Harrison Act reset the Volstead definition to 3.2% ABV and thereby legalized light beers. This saw a brief drop in liquor traffic, though the trade rebounded quickly. Rum-running had almost returned to 1932 levels, at least off of New York, when the 21st Amendment drove rum-running to an absolute low during the case. This lasted for about six months.

An period newspaper article entitled “Rum Runners Want Repeal, U.S. Informed,”[2] explains the rumrunners’ optimism toward their post-repeal prospects. Both Canada and Finland attempted their own forms of Prohibition, and both experienced major smuggling problems following repeal. Rumrunners expected the same to be true of the United States, due to a combination of high expected liquor taxes, reduced enforcement expenditures and diminished legal leverage following repeal.

The country would want a ‘peace dividend,’ which meant less money going to the Coast Guard. Additionally, the Coast Guard would now need to establish the origin of alcohol, rather than just its presence, in order to arrest a rumrunner in US waters. Once the liquor was ashore, it now became far easier to transport. Therefore, that rum-runners no longer needed to concentrate at urban centers close to the point of demand, and the Coast Guard would need a “less concentrated and more wide-flung patrol of the coasts.”[3] These reduced the opportunity cost of smuggling, and so long as there was enough of a margin in the liquor taxes to make money, there was no reason to stop running.

The Coast Guard attempted to calculate this margin. Shortly following repeal, Gorman estimated that imported liquor in the New England area cost $9.90/gal, $9.30 of which was composed of State, Internal Revenue and Customs taxes.[4] The smuggler, paying the same price for liquor, could land liquor for $1.10/gal. The price they would expect to receive on the beach was $1.90/gal in Maine, $2.50/gal in Massachusetts, and $3.25/gal in New York. This yields a margin of more than two dollars per gallon. A September 1934 calculation found legal liquor selling for $8/gal, with bootleg at $6/gal. Even with this premium for licit drink, the rumrunner still had margin of about one and a half dollars per gallon.[5]

Profits were lower than during Prohibition, but the risk was lower as well due to diminished enforcement leverage. Making matters worse, Americans thirsted for aged whiskey, and none would be available domestically for quite some time. Since the rumrunner bases at St. Pierre had a great deal of capital tied up in smuggling, there was no sense in dismantling the industry quite yet.

‘Peace Dividend.’ Even before repeal, the Intelligence Office noted in 1933 that:

Vessels formerly in the rum running traffic, which had been laid up for months and in some cases years, are now being outfitted and rushed back into the illicit traffic. Recent official reports from Canadian sources indicate during the past month a resumption of activity comparable only to the situation which existed several years ago before the Coast Guard was organized to effectively combat smuggling. International rum syndicates are quite evidently under the impression that law enforcement will be more lax than formerly; that penalties meted out for violations of the Customs laws will be much lighter and that in general there will be less risk and more profit in liquor running…

It therefore appears to this office from a study of smuggling conditions in foreign countries and from knowledge of the present activities of the rum-smuggling rings, that there can be no curtailment of Coast Guard anti-smuggling operations until the international smuggling organizations now operating are put out of existence, and it can be said almost with certainty that this will not occur within the next two years.[6]

Institutional militaries try to minimize the inevitable drawdown that follows the end of a war, and these gloomy predictions must have sounded like that familiar chord. Policy analysts from early think tanks broadly agreed, estimating $50 Million per year lost per year to liquor smuggling.[7] This was more than 10% of the expected alcohol excise tax income. Still, increasing enforcement of liquor laws during the Depression in the immediate wake of Prohibition was too politically difficult. From a 1934 account, “repeated requests of the Coast Guard for funds, necessary to carry out its duties, particularly to control smuggling, and to protect the revenue of the Government, have been denied.”[8] The Coast Guard would draw down.

Destroyers departed the force entirely, with the last of them returned to the Navy by 1934. The ‘six-bitters’ took a major hit, dropping from 58 in 1934 from 203 in 1931.[9] The cruising cutters, and larger patrol boats retained most of their force. Picket boats were halved from 195 to 109. The number of lifesaving stations remained stable, but the suppression-oriented section bases fell from nineteen to three. Aircraft inventory and the number of 165-foot patrol boats continued to grow through July 1934. These two types of craft partially offset the patrolling vacuum left by the destroyers. The patrol craft and bases were not offset at all.

The manning situation was worse. According to a 1934 memo, “Not only has the Coast Guard felt these losses of men and units, but the drastic, quick retrenchment occasioned thereby, has been a serious blow to the morale and, therefore, the efficiency of the remaining force… funds for the payment of enlisted personnel for the current year are inadequate, and unless the situation is relieved, it will be necessary to discharge or disrate, or furlough without pay, additional men.”[10] The memo’s author, likely the Commandant, asserts “such a step would be a serious reflection upon the Federal Government in breaking faith with men of long and faithful service to their country… a breach of implied contract on the part of the Government.”[11] This was a disheartening time for the service.

In some cold solace, the dour predictions of resurgent smuggling proved correct. By the summer of 1934, there were as many boats hovering off of New York as in 1928 and climbing fast. An estimated $30 Million of revenue was lost in 1934, and if unchecked, 1935 promised to double that number at least. Since the Canadians had been losing something in the range of $30-45 Million per year under similar conditions, this should not have been a surprise.[12] The form of this smuggling was familiar – the trade picked up where it left off with the same radio-linked swift stealth ships.

Rebuilding. Given that the Coast Guard ‘peace dividend’ was only $10 Million per year, the government began to see the reduction in forces as a bad investment. The half-sized, demoralized force could be swarmed and defeated, especially without its scouting destroyers or an adequate number of replacements. The second half of 1934 saw a reversal of the decline and a re-capitalization of Coast Guard forces. This buildup registered primarily in the new large patrol boats and in Aviation, and it allowed the Coast Guard to complete a restructuring it began in 1930.

Admiral Billard launched a service reorganization project during his last year as Commandant.[13] Admiral Hamlet carried it through to completion as the drawdown set in, doing away with the various overlapping lifesaving, patrol and cruising forces and consolidating regional divisions under single commanders. Henry Morgenthau, the new Secretary of the Treasury, asked Coast Guard to take the lead of all Treasury organizations in these districts – having one clear commander who curated diverse capabilities aided interagency coordination.

The divisional structure also worked well with the growing intelligence and aviation capacities, provided the relationships within these divisions were as flat as the Commandant’s guidance intended. Notably, when these organizations were run hierarchically, these special units did not do as well. Commanders that directed actions from the top, yet lacked the technical knowledge to grasp these capabilities, failed to make effective use of these cells. Case in point – Wheeler and the aforementioned breakdown with his Intelligence Lieutenant in the California Division.[14] In general, though, this structure allowed the diverse technical capabilities developed over the course of the campaign to be smoothly brought to bear at the front lines.

The return of funding put substance on the divisional framework. By the beginning of 1935, 18 Thetis-class 165’ patrol ships were operational. This was up from nine half a year prior, and six as of 1932. These were Wheeler’s replacement for the Destroyers – six knots faster than the ‘buck-and-a-quarters’ and designed with a tight turning radius, they could stay with the new generation of fast rum ships at a fraction the cost of a Destroyer. They performed this task well, and along with the still-new Lake-class fast cutters, the remaining half of the patrol fleet, and the still-rapidly-advancing SIGINT capabilities.

The Secretary of the Treasury built a seven-fold plan for the renewed campaign. From a 1935 memo recounting the strategy, “the measures undertaken included:

a) Provision of funds to permit of increased activity by the Coast Guard and stimulation of effort on its part as the marine patrol agency. [NB: Support.]

b) Determination of the sources of supply of contraband and negotiations to obtain the assistance of other governments in checking the illicit traffic. [Diplomacy.]

c) Coordination of the efforts of all Treasury Department law-enforcement agencies having any connection with the problem by means of regional coordinators and the establishment of a ‘law-enforcement’ council or committee at Washington, composed of representatives of the various agencies. Frequent conferences at Washington and in the field contributed to this coordination. [Interagency Fusion.]

d) A study of the legal deficiencies hampering effective efforts against the smugglers and the drafting of a bill strengthening enforcement powers, for presentation to Congress. [Legal, Anti-Smuggling Act of 1935.]

e) Stimulation of sources of information to permit of intelligent action being taken. [Intelligence.]

f) Vigorous prosecutions where cases could be made. [Courts, a major prior deficiency.]

g) Close cooperation with agencies of the Canadian Government, which has a problem of like character. [NB: International Fusion.]”[15]

These were all the result of costly lessons learned. With this strategy in place, the last major campaign began.

…

The combination of a recapitalized patrol fleet, robust intelligence capabilities, and a burgeoning air fleet formed the final model of the rum war. The Commandant explained this fusion of sea, air and intelligence in a 1934 tactics bulletin:

The Intelligence boat (or any unit suitably equipped) detects black radio traffic and obtains a radio bearing. The air station of plane (standing by) is notified of the bearing of the “black.” The plane takes the air and flies to the position of the patrol boat and passes over her on the course (corrected navigationally) corresponding to the bearing. Upon reaching the black the radio-equipped plane circles overhead and calls for radio bearings from all direction-finder units… The bearings are transmitted by units taking them together with the latter’s positions to a designated patrol unit, and the plot places of the position of the “black” which can then be sought and trailed.

If the rumrunners abandoned their radios, the aircraft could still search for them. There was no way to outrun or hide from an aircraft, other than inclement weather. And the circling aircraft could call a cutter at its convenience. This rumrunner-hunting model offered no ready counter.

Remarkably, this model parallels the “Find-Fix-Finish” approach of counter-terror fame.[1] In order to beat this approach, the rumrunners would have had to re-boot their entire business model. This would have been costly. Social support had begun to turn against them following repeal – no longer romantic outlaws, legal alcohol had made the rumrunners just outlaws. From an intelligence memo in 1935:

Unmentioned previously herein is the effect of a changed public attitude following Repeal. This has been very helpful in contributing to control. Many who were hostile to enforcement efforts during Prohibition are today either indifferent or openly favorable.[2]

Therefore, they could no longer recoup losses or recapitalize the way they once had. A reboot was impossible, and the end of the large-scale illicit liquor trade was just a matter of time.

Only $6.5 Million was lost from the treasury due to liquor smuggling in 1935, around 20% of the 1934 number. The last spike of the rum trade was in the early summer of 1935, and it fell precipitously from there. From the same 1935 report:

As a result of the cumulative effect of the efforts expended by the Government the organizations and individuals promoting smuggling have suffered a severe blow. Efforts are being exerted by them to develop new methods of supply such as chartering vessels to transport cargoes from Europe for delivery on the high seas to smaller vessels or to run directly into large ports where maritime traffic is great and there is the possibility of slipping in as a legitimate vessel not subject to routine inspection. This is an effort on the part of those to whom ‘easy money’ has been the fondest recollection of the heyday of the smuggling traffic. There will always be smuggling in some form and amount but liquor and alcohol smuggling as evidenced during the last fiscal year is declining as a major problem under the pressure exerted by the Government.[3]

What little of the trade remained had fizzled out by 1936, with the liquor ships melting back into the Nova Scotia fishing fleet, or in a few cases, hardening into opium or migrant smugglers. Coast Guard Intelligence ceased tracking suspected Rumrunners entirely on account of irrelevance by 1939. Operational life returned to traditional lifesaving missions and routine law-enforcement by 1936 with the end of organized rum-running.

[1] Charles Faint and Michael Harris, “F3EAD: Ops/Intel Fusion ‘Feeds’ The SOF Targeting Process,” Small Wars Journal, 2012, http://smallwarsjournal.com/author/charles-faint-and-michael-harris.

[2] Parker (?) memo. RG 26, NARA.

[3] Ibid.

[1] Bruce Yandle, “Bootleggers and Baptists-The Education of a Regulatory Economists,” Regulation 7 (1983): 12.

[2] Unidentified Clipping. RG 26, NARA.

[3] Gorman Memo. RG 26, NARA.

[4] Cost Calculation Memo. RG 26, NARA.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Intelligence Memo. RG 26, NARA.

[7] Newspaper Clippings. RG 26, NARA.

[8] Memo. RG 26, NARA.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Lawlor, Rum-Running. 93. ‘The customs revenue went down between $70 and $90M in two years’ – it is unclear whether this is per year or total, but I assumed the former. Since the 1930 US Dollar was 2.07 Canadian dollars, dividing by two accounts for the currency conversion. Depending on the estimate, this could be cut in half once more if the $75-90M was an aggregate number. Either way, there was some non-trivial sum of smuggling losses.

[13] Billard Memo. RG 26, NARA.

[14] Wheeler CA memo, 1934 (?). RG 26, NARA.

[15] Parker(?) 1935 Memo. Reflected verbatim in Waesche 1938 Memo. RG 26, NARA.