Project SIXTY was Admiral Elmo “Bud” Zumwalt’s plan of action for his term as Chief of Naval Operations, lasting from July 1, 1970 to June 29, 1974. In it Admiral Zumwalt describes a resurgent naval threat from a peer competitor, the need to rebalance the mission focus between sea control and power projection, and how to optimize the fleet in the context of budgetary pressures.

Project SIXTY will be republished here on CIMSEC in three parts. This republication is drawn from the U.S. Naval War College’s Newport Papers, specifically “U.S. Naval Strategy in the 1970s, Selected Documents” edited by John B. Hattendorf.

Memorandum For All Flag Officers (And Marine General Officers, Dated SEP 16, 1970

Subj: Project SIXTY

1. In July I told you that I would make an assessment of the Navy’s capabilities and problems for a presentation to the Secretary of Defense in early September. With the benefit of your insights and assistance, this task, Project SIXTY, has been completed. Secretary Chafee and I made the presentation on 10 September to Secretaries Laird and Packard and follow-on discussions with them are scheduled.

2. I consider that the substance of this presentation sets forth the direction in which we want the Navy to move in the next few years. The decisions that we make, and implement, at the command levels of the Navy should be consistent with these concepts. Further, I am passing this paper to the CNO Executive Panel, and its Programs Analysis Group, as the primary guideline for their deliberations in advising me on actions we should take and on the suitability of current programs. The Panel will consider the Project SIXTY paper as a dynamic statement of the direction that the Navy is to move and will adapt new concepts and ideas to keep the guidelines current and in-step with the threat and our best thoughts.

3. I am forwarding the Project Sixty Presentation to you, under cover of this letter, to guide your actions as well to keep you fully aware of my thinking and to encourage your support as we move ahead.

My purpose today is to report to you on our naval strengths and weaknesses and the actions we are taking, or will propose, to achieve the highest feasible combat readiness. The report reflects our survey of the Navy to date and sets forth the change of direction which we think necessary. It is impossible to discuss these changes outside the context of potential budget reductions. We will indicate the effect of such reductions; they would curtail our capabilities critically, regardless of our actions. However, we hope to emphasize the theme of the changes that we feel must be undertaken, whether we can maintain our present expenditures or not.

The Navy’s capabilities fall naturally into four categories:

NAVAL CAPABILITIES

- ASSURED SECOND STRIKE

- CONTROL OF SEA LINES AND AREAS

- PROJECTION OF POWER ASHORE

- OVERSEAS PRESENCE IN PEACETIME

- Assured Second Strike Potential,

- Sea Control by our attack submarines, dual-mission carriers, escorts, and patrol aircraft,

- Projection of power ashore by our dual-mission carriers and the amphibious force, and

- Overseas presence in peacetime

We want to see where each of these capabilities fits into the possible conflict situations that we may face in the decade ahead. What, in short, does the country require of its sea forces?

SIGNIFICANT CHANGES IN SOVIET THREAT OF LATE ’60s

- NUCLEAR PARITY

- EMERGENCE OF STRONG, WORLDWIDE DEPLOYED SOVIET NAVY

We are looking at this matter at a time when two factors have developed, of the highest importance to the power relationship between the U.S. and the Soviet Union:

- Nuclear parity, and

- The emergence of a strong, worldwide-deployed Soviet Navy

ASSURED SECOND STRIKE POTENTIAL

The initial Navy capability is the contribution it can make to an assured Second Strike potential.

Strategic deterrence must come first. Soviet achievement of nuclear parity, deployment of SS-9’s, and potential deployment of MIRVs have all raised the value of our sea-based strategic forces, and we are close upon the point when more of our deterrent forces will have to be based more securely. We are confident that the Navy can design and build a secure, effective ULMS (Underwater Long Range Missile System). If the national decision is to rely more heavily on sea basing— that is, to have ULMS operating before 1980—we must soon decide to accelerate.

SEA CONTROL AND PROJECTION

The other major naval missions at sea involve our sea control and projection forces.

The recent changes in relative strategic power between the Soviets and ourselves also have important implications for these conventional forces.

SEA CONTROL AND PROJECTION

NUCLEAR-CONVENTIONAL RELATIONSHIPS

- SEA CONTROL GUARANTEES INVULNERABILITY OF SEA BASED MISSILES

- NUCLEAR PARITY INCREASES LIKELIHOOD OF CONVENTIONAL CONFLICT

On the one hand, the credibility of our ability to control the sea is essential to the credibility of our strategic sea-based deterrent. On the other hand, now that we have lost our superiority and are reducing our conventional forces, the Soviets are more likely to use military force to achieve their political objectives. The importance of the portion of our conventional force that is capable of overseas presence has thus been increased.

SEA CONTROL AND PROJECTION

- NIXON DOCTRINE

- NEW SOVIET NAVAL CAPABILITY

From the naval standpoint, these relationships are influenced further by the Nixon Doctrine and by the large, modern Soviet Navy that emerged in the 1960s.

The continuing withdrawal of the United States from foreign bases and—in Asia—the change in the forms of armed support we plan to make available to our allies, place additional responsibilities on our sea control and projection forces. Both will employ the dual mission carrier—the new CV concept. The Sea Control forces will see to it that sealift supplies get through to our allies. Projection forces will maintain a ready deterrent to avoid any misunderstanding of our intent and provide support promptly if needed. The Nixon Doctrine has effectively raised the threshold at which we would commit land forces overseas. We have moved closer to a situation in which Soviet or CHICOM involvement is the primary circumstance that might force us to intervene. We therefore face conventional war that will not include the sanctuary of full use of our sea lines of communication. The Soviets have conceded us this luxury in the past, in part because of our nuclear superiority, in part because of their belief that we could defeat them at sea in conventional war.

But now the Soviet Navy has evolved impressively in both size and spectrum of capabilities. Its technical and industrial base operates at high levels of design, development, and production. The Soviet Navy has been constructing and deploying submarines and surface ships at an ominously high rate. The quantity and technical quality of these ships has been rising sharply.

What does this new Soviet naval capability mean to us?

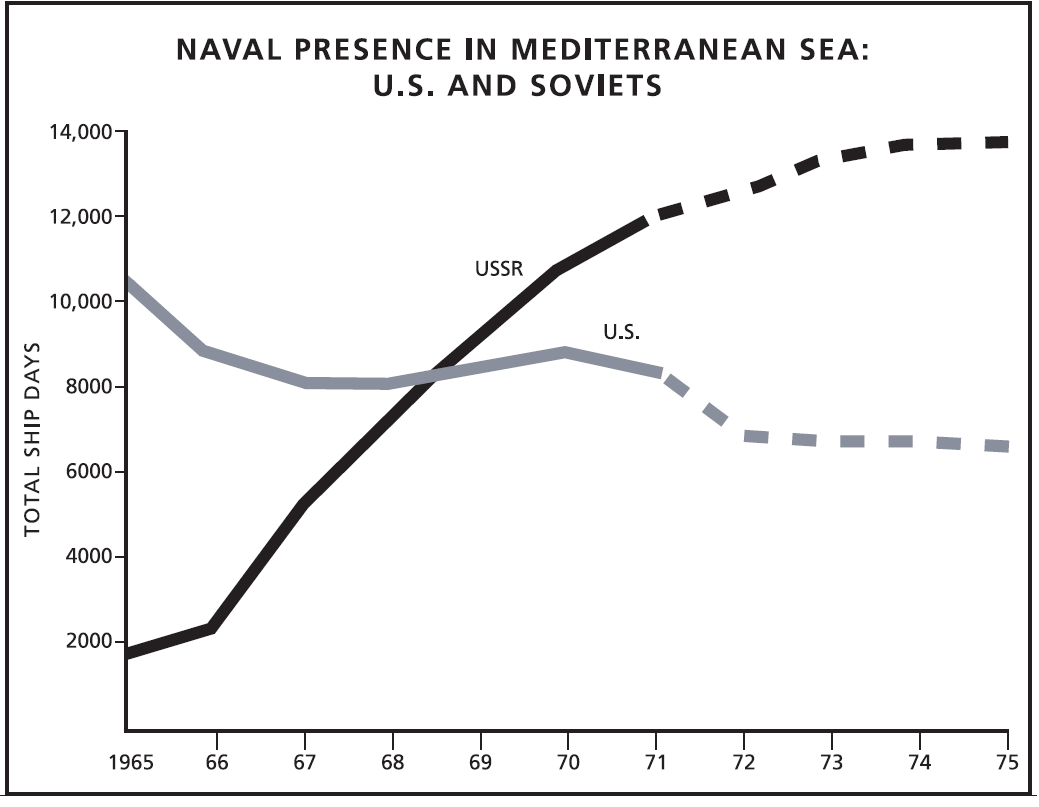

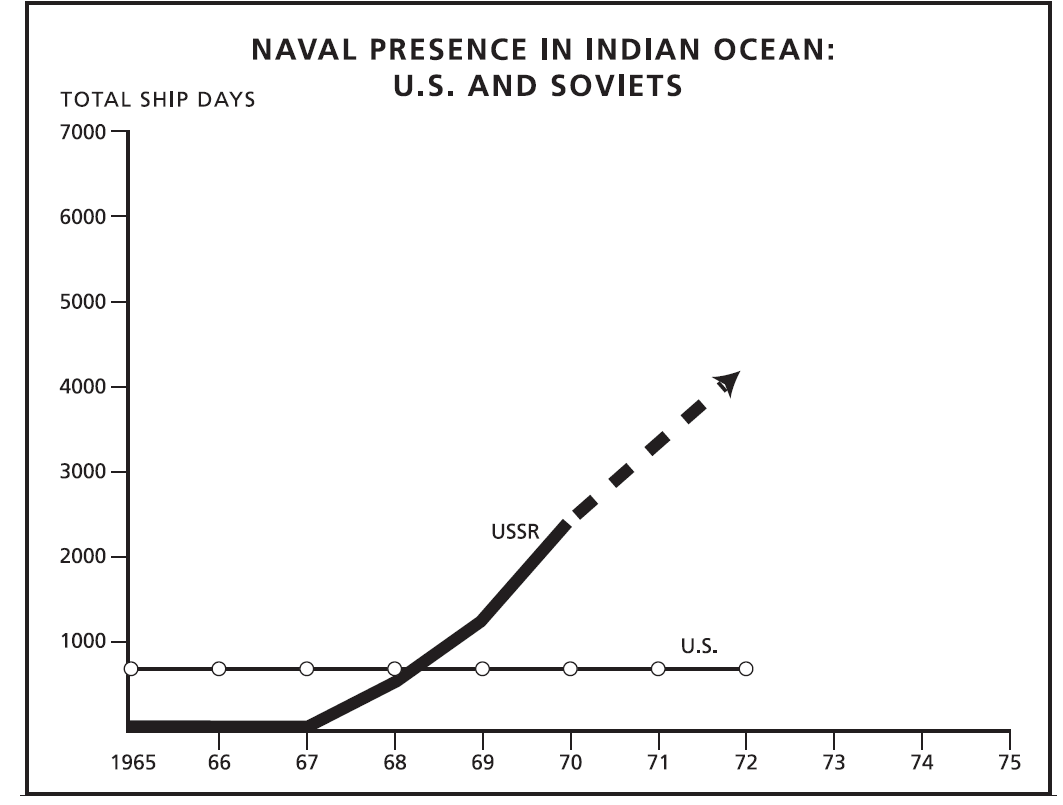

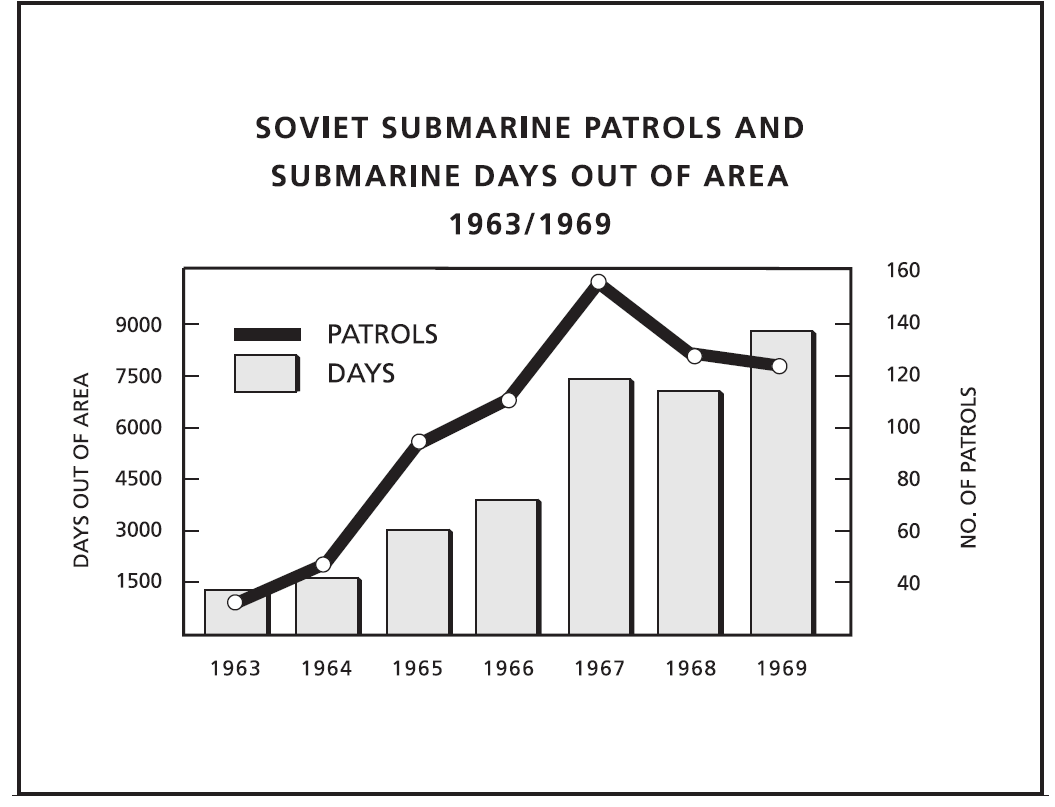

In strategic terms, the Soviet Navy is a worldwide force whose routine deployments reach into the Mediterranean Sea, the Indian Ocean, and Caribbean, as well as the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Today the Soviet naval presence in the Mediterranean is as great as ours; 10 years ago it was negligible. We devote fewer than 800 ship days a year to limited parts of the Indian Ocean; the Soviets’ reach over that area has gone from zero ship days to 2400 in the past 3 years. Their submarine activity is four times as intense as ours and covers all the sea lanes of the world.

As you know, the Soviets have more attack submarines than we do. And they are building at a rate of 10–14 a year; we are building three. The Soviets are reducing the advantage we had in quality by building new, quieter classes of submarines. These new submarines have unique features that are so good we may copy them. In just two years, the Soviets have produced at least 6 new designs in submarines. Their new attack submarines are 3½ to 5½ knots faster than ours. Beyond this, they are giving priority to the Yankee-class ballistic missile submarines, building them at a rate of 6 to 8 a year.

SEA CONTROL AND PROJECTION

- SOVIET SUBMARINES

- 10–14 NEW SSNs PER YEAR

- QUIETER

- NEW DESIGNS (FASTER)

- PRIORITY TO YANKEE CLASS SSBNs (6–8/YEAR)

These factors give the Soviets several advantages:

SOVIET ADVANTAGES

- INCREASED OUT OF AREA PATROLS

- DECREASED U.S. ACOUSTIC ADVANTAGE

- SPEED

- With greater numbers of submarines, routine out of area deployments can be increased without alerting our intelligence. Their readiness to fight is kept at a high level.

- Quieter submarines decrease the acoustic advantage on which our submarine barriers and underseas surveillance systems depend to detect Soviet submarine transits.

- Their speed advantage permits the Soviet submarines to use leap-frog tactics and brute speed in attack or evasion underseas.

YEARLY CONSTRUCTION OF NUCLEAR SUBMARINES

| NOW BUILDING | CAPACITY | Avg. time to build 1 Sub. | |

| USSR | 14–20 | 35 | 21 MOS. |

| U.S. | 3 | 6* | 27 MOS. |

*WHEN POSEIDON IS COMPLETE, U.S. CAPACITY WILL BE 10–12 A YEAR.

And, highly important, the Soviets, with their large capacity and high building rate, can exploit technical improvements more rapidly than we can. They have a potential production level of 35 nuclear submarines a year without facility expansion.

GROWTH IN SOVIET MISSILE-LAUNCH PLATFORMS

| 1960 | 1970 | |

| MAJOR MISSILE WARSHIPS | 6 | 49 |

| MISSILE PATROL BOATS | 6 | 158 |

| CRUISE MISSILE SUBMARINES | 0 | 62 |

| RECONNAISSANCE AND MISSILE AIRCRAFT | 215 | 454 |

| TOTAL | 227 | 723 |

The Soviets have concentrated on weapons for use at sea. This chart shows the buildup in missile-launching vehicles in their naval inventory.

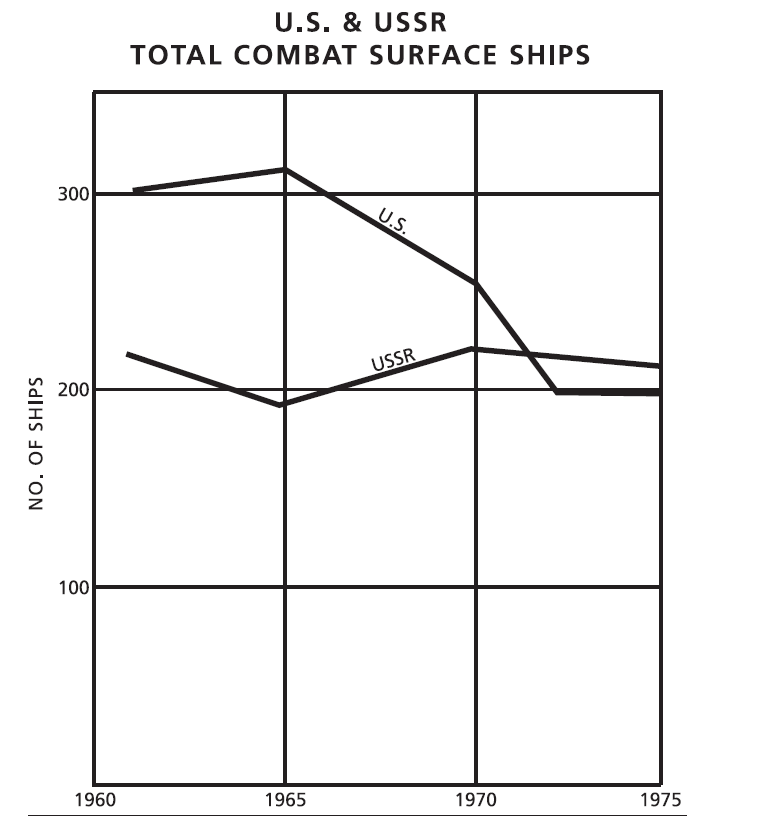

Their surface fleet continues to grow in size and quality relative to ours.

US VS USSR GENERAL PURPOSE NAVAL SHIP CONSTRUCTION 1966–1970

| US | USSR | USSR/US IN % | |

| MAJOR COMBATANTS | 11 | 17 | 155 |

| MINOR COMBATANTS | 47 | 182 | 387 |

| AMPHIBIOUS SHIPS | 14 | 6 | 43 |

| ATTACK SUBMARINES | 26 | 43 | 165 |

They are building more ships than we are; amphibious ships are the only category in which we have been outbuilding them.

And the Soviets are enhancing the effectiveness of these forces with a high quality capability for electronics warfare and communications. This includes active and passive countermeasures directed at our systems, intercept equipment covering all of our emitters, and excellent facilities for communications jamming, deception, and intelligence. These assets are drawn together by a highly secure, worldwide communications system.

The Soviet Navy I have touched on here can be deployed in all the oceans. To maintain our own position, our Navy must be based on the two-ocean concept. We cannot concentrate forces in one ocean unless we are prepared to accept in war the loss of control of the other oceans—and thus the destruction of the Free World Alliance.

As an example of this limitation, in the first naval capability to be examined—that of support of war on land—we have looked at alternative ways to provide lift across the Atlantic. The lift mission cannot be performed by air alone. For a NATO war in the mid-1970’s, JCS plans call for moving seven million tons of military dry cargo and five million tons of military POL in the first six months. Of this total only 6% could be moved by air. This is consistent with our experience in Southeast Asia, where 96% has moved in ships.

SEALIFT IS ESSENTIAL

- IN A NATO WAR IN THE MID 1970’S, AIRLIFT WILL BE ABLE TO HANDLE ONLY 6% OF MILITARY CARGOES REQUIRED

- IN SOUTHEAST ASIA, ONLY 4% HAS MOVED BY AIR

Heavy reliance on sealift is an integral part of the U.S. role as a sea power. It emphasizes the absolute need to be able to control the seas if the nation is to exist. This slide shows why the sea control role must be a main concern of the U.S. Navy. Seaborne trade is several times more important to the U.S. than to the Soviets. Oceans lie between us and our allies; most of the Soviet alliances are with contiguous nations.

SEABORNE TRADE

(MILLIONS OF LONG TONS)

| 1958 | 1965 | |

| U.S. | 274 | 395 |

| USSR | 26 | 90 |

ALLIANCES

| WITH CONTIGUOUS NATIONS | WITH NON-CONTIGUOUS NATIONS | |

| U.S. | 2 | 43 |

| USSR | 7 | 4 |

POTENTIAL ENEMIES

U.S.: NO CONTIGUOUS ENEMIES

USSR: CHINA AND NATO

Support of war-on-land requires not only the ability to lift forces across the seas but also the ability to project power ashore.

At reduced force levels, we should be concerned about the threat to sea projection forces during the early days of a NATO war. The situation on each flank is different.

NATO WAR

MEDITERRANEAN THREAT FACTORS

- CONTINUOUS OPERATIONS OF SOVIET SHIPS

- SOVIET ACCESS TO PORTS

- SOVIET USE OF AIRFIELDS

A combination of factors has given rise to a serious threat in the relatively restricted sea area of the Mediterranean. There are three such factors:

1. Continuous operation of Soviet ships in the Mediterranean,

2. Soviet access to ports that were closed to them less than a decade ago, and

3. Soviet use of airfields in the UAR and Libya.

Because we lack adequate surveillance capabilities, we cannot keep full-time track of Soviet submarines in the Mediterranean. For their part, the Soviets’ surface ships trail our carriers, ready for a first-strike attack in the event of conflict.

Yet, the Soviet naval presence in the Mediterranean demands militarily that we maintain our SIXTH Fleet at generally current force levels. Politically, the whole ambience of NATO requires us to assume that those forces—or augmented forces—will be in place and subject to early and very heavy attack at the outbreak of hostilities.

On the northern flank, however, political circumstances do not require our permanent or prior presence. Hence, before moving in to support forces on land, we would probably operate from mid-ocean to erode the Soviets’ submarine force, sweep up their surface ships and, as Allied land-based air operations took effect, slow down the rate of sorties from enemy air bases.

These considerations also raise the question of the importance of the naval air strike responsibility in NATO. NATO plans call for using all our carriers in this role. Because of air base shortages in Europe and competitive SAC requirements for tankers, I consider that mission of central value in holding the line on the NATO flanks until planned Air Force reinforcements can be deployed from CONUS. Though some feasible measures will reduce the naval problem, the essential deficiency is in forces.

I should add that strategic warning does not lessen the Soviet naval threat, but it might give us time to move our forces from the Pacific. Strategic warning might also permit the Air Force to make deployments, though bases would be a limiting factor.

Support of the land battle in a NATO war would thus require naval carrier strike forces. Therefore, most of our sea control forces would be engaged in protecting these projection forces. There would be little left to provide more than random security to the sea lines of communications. We would then be ceding to the Soviets this linchpin of rapid reinforcement upon which NATO depends to stabilize the conflict on land and reduce the likelihood of escalation.

Within likely budgets, this heavy commitment in one ocean would, in our judgment, require the movement of naval forces from the Pacific, abandonment of the Pacific area west of Hawaii, and cession of control of those waters—including all of Japan, for instance—to the Soviet Far East Fleet. We can also lose sea control in the Atlantic as a result of events in the Pacific. The Soviets can give direct or proxy support to a North Korean attack on South Korea. The logical first response to that situation, as in South Vietnam, would be strikes by our carrier aircraft. Our analysis of the threat in the Sea of Japan at the time the EC-121 was shot down indicates a requirement for at least four carriers, with large protecting forces. Again, within likely budgets, our forces will be inadequate for sea control in the Pacific in the face of Soviet involvement—or threat of involvement—at sea, unless we move the bulk of our naval forces to the area. But that would cost us control of the Atlantic and the sea lines that support NATO.

These considerations present us with a number of hard alternatives in the face of budget reductions, if the Navy is to be in a position to make the necessary contribution to the nation’s security.

ALTERNATIVES

- COMMIT ALL NAVAL FORCES TO SEA CONTROL

- CONCENTRATE FORCES IN ONE OCEAN

- INCREASE FORCES TO A LEVEL COMMENSURATE WITH TWO-OCEAN NEEDS

- One course would be to commit all or nearly all the forces available, including the carriers, to the sea control mission. If so, the NATO air strike responsibility would have to be significantly reduced or even eliminated. In Asia, the cutting edge provided by attack carriers in a situation such as Korea would be reduced drastically if the Soviets chose to become involved at sea. At our lower force levels, we simply could not risk the irretrievable loss of sea control by hazarding our few carriers in land battles close to Eurasia.

- Another course would be augmentation of forces from one ocean to the other in time of crisis or conflict, as an integral part of our strategic planning. If so, we would have to accept the risk or actual fact of Soviet control of the other seas and the implications of that result for the Free World Alliance.

- The only real solution is maintenance of forces at the FY-1970 level or, for greater assurance, an increase of forces. This alternative will retain the naval option to provide the President with a mobile strategic contingency force whenever required and ensures greater confidence in our capability to support the deployment of Army and Air Force units.

Let me speak now of other naval capabilities that are required and that will fit into the force implications just discussed in the war-on-land case.

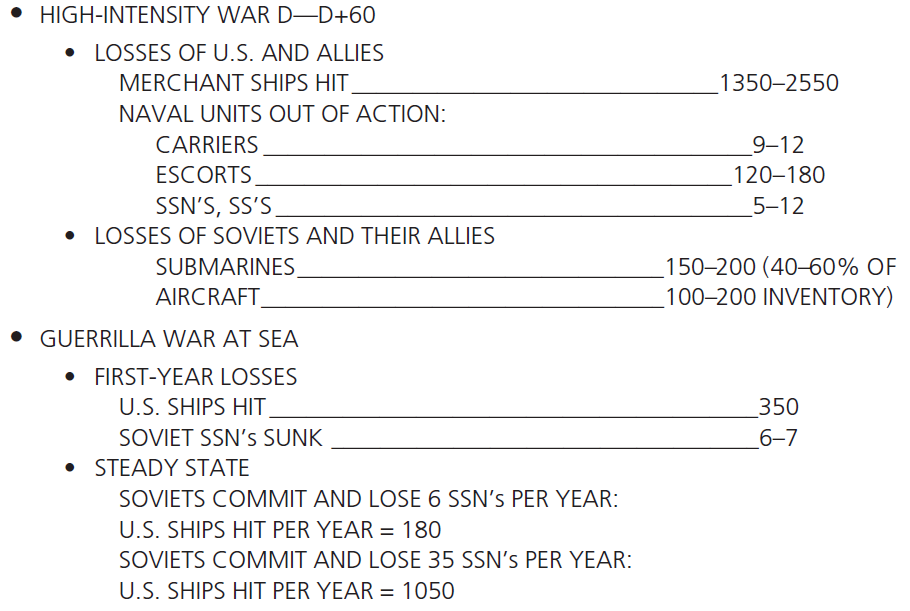

In addition to possibly contesting for control of sea lanes incident to a war on land, the Soviets’ naval strength enables them to start a war restricted to the sea. Such a conflict could be directed at Free World merchant shipping, at our naval forces, or at some combination of the two, the choice depending on the Soviets’ objective. The Soviets might also wage such a war by proxy.

If we were not already engaged in conflict, we could commit maximum available forces immediately to the sea control mission. There would be no conflicting requirements for projection of power ashore, though our ability to provide a strategic contingency force for another crisis would be reduced. This slide shows the results of a recent study of such a war at sea, including a high intensity war and a guerrilla war at sea. The study assumed present force levels projected ahead. In this study, our losses are heavy. They would be heavier at the lower levels we are now planning on.

How our allies—we—and the Soviets estimate the outcome of such a conflict could have a significant influence on responses to other situations. The Soviets surely gave this matter prominence in their decisions during the Cuban missile crisis. In our judgment, their naval course since that time originated then. Whether any President will ever again be willing to impose a blockade will depend on his assessment—and ours— of the risks if war at sea were to result. His decision will also depend on whether we proceed now to provide him with credible tools. To expect our allies to help us counter a Soviet initiative at sea will depend primarily on their view of our ability to pursue such a conflict successfully.

Admiral Elmo “Bud” Zumwalt served as the nineteenth Chief of Naval Operations of the U.S. Navy, from 1970-1974.

Featured Image: Admiral Elmo R. Zumwalt. Jr., USN, Chief of Naval Operations (left), and Rear Admiral Robert S. Salzer, USN, Commander Naval Forces Vietnam, discuss their recent visit to Nam Can Naval Base, Republic of Vietnam, as they fly to their next stop, May 1971. Official U.S. Navy Photograph.