The following article is part of our cross-posting partnership with Information Dissemination’s Jon Solomon. It is republished here with the author’s permission. You can read it in its original form here.

Read part one of this series here.

By Jon Solomon

Candidate Principle #2: A Network’s Combat Viability is more than the Sum of its Nodes

Force networking generates an unavoidable trade-off between maximizing collective combat capabilities and minimizing network-induced vulnerability risks. The challenge is finding an acceptable balance between the two in both design and operation; networking provides no ‘free lunch.’

This trade-off was commonly discounted during the network-centric era’s early years. For instance, Metcalfe’s Law—the idea that a network’s potential increases as the square of the number of networked nodes—was often applied in ways suggesting a force would become increasingly capable as more sensors, weapons, and data processing elements were tied together to collect, interpret, and act upon battle space information.[i] Such assertions, though, were made without reference to the network’s architecture. The sheer number (or types) of nodes matter little if the disruption of certain critical nodes (relay satellites, for example) or the exploitation of any given node to access the network’s internals erode the network’s data confidentiality, integrity, or availability. This renders node-counting on its own a meaningless and perhaps even misleadingly dangerous measure of a network’s potential. The same is also true if individual systems and platforms have design limitations that prevent them from fighting effectively if force-level networks are undermined.

Consequently, there is a gigantic difference between a network-enhanced warfare system and a network-dependent warfare system. While the former’s performance expands greatly when connected to other force elements via a network, it nevertheless is designed to have a minimum performance that is ‘good enough’ to independently achieve certain critical tasks if network connectivity is unavailable or compromised.[ii] A practical example of this is the U.S. Navy’s Cooperative Engagement Capability (CEC), which extends an individual warship’s air warfare reach beyond its own sensors’ line-of-sight out to its interceptor missiles’ maximum ranges courtesy of other CEC-participating platforms’ sensor data. Loss of the local CEC network may significantly reduce a battle force’s air warfare effectiveness, but the participating warships’ combat systems would still retain formidable self and local-area air defense capabilities.

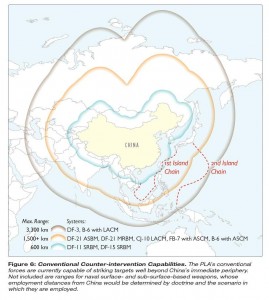

Conversely, a network-dependent warfare system fails outright when its supporting network is corrupted or denied. For instance, whereas in theory Soviet anti-ship missile-armed bombers of the late 1950s through early 1990s could strike U.S. aircraft carrier battle groups over a thousand miles from the Soviet coast, their ability to do so was predicated upon time-sensitive cueing by the Soviet Ocean Surveillance System (SOSS). SOSS’s network was built around a highly centralized situational picture-development and combat decision-making apparatus, which relied heavily upon remote sensors and long-range radio frequency communications pathways that were ripe for EW exploitation. This meant U.S. efforts to slow down, saturate, block, or manipulate sensor data inputs to SOSS, let alone to do the same to the SOSS picture outputs Soviet bomber forces relied upon in order to know their targets’ general locations, had the potential of cutting any number of critical links in the bombers’ ‘kill chain.’ If bombers were passed a SOSS cue at all, their crews would have had no idea whether they would find a carrier battle group or a decoy asset (and maybe an accompanying aerial ambush) at the terminus of their sortie route. Furthermore, bomber crews firing from standoff-range could only be confident they had aimed their missiles at actual high-priority ships and not decoys or lower-priority ships if they received precise visual identifications of targets from scouts that had penetrated to the battle group’s center. If these scouts failed in this role—a high probability once U.S. rules of engagement were relaxed following a war’s outbreak—the missile salvo would be seriously handicapped and perhaps wasted, if it could be launched at all. Little is different today with respect to China’s nascent Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile capability: undermine the underlying surveillance-reconnaissance network and the weapon loses its combat utility.[iii] This is the risk systems take with network-dependency.

Candidate Principle #3: Contact Detection is Easy, Contact Classification and Identification are Not

The above SOSS analogy leads to a major observation regarding remote sensing: detecting something is not the same as knowing with confidence what it is. It cannot be overstated that no sensor can infallibly classify and identify its contacts: countermeasures exist against every sensor type.

As an example, for decades we have heard the argument ‘large signature’ platforms such as aircraft carriers are especially vulnerable because they cannot readily hide from wide-area surveillance radars and the like. If the only method of carrier concealment was broadband Radar Cross Section suppression, and if the only prerequisite for firing an anti-carrier weapon was a large surface contact’s detection, the assertions of excessive vulnerability would be true. A large surface contact held by remote radar, however, can just as easily be a merchant vessel, a naval auxiliary ship, a deceptive low campaign-value combatant employing signature-enhancement measures, or an artificial decoy. Whereas advanced radars’ synthetic or inverse synthetic aperture modes can be used to discriminate a contact’s basic shape as a classification tool, a variety of EW tactics and techniques can prevent those modes’ effective use or render their findings suspect. Faced with those kinds of obstacles, active sensor designers might turn to Low Probability of Intercept (LPI) transmission techniques to buy time for their systems to evade detection and also delay the opponent’s development of effective EW countermeasures. Nevertheless, an intelligent opponent’s signals intelligence collection and analysis efforts will eventually discover and correctly classify an active sensor’s LPI emissions. It might take multiple combat engagements over several months for them to do this, or it might take them only a single combat engagement and then a few hours of analysis. This means new LPI techniques must be continually developed, stockpiled, and then situationally employed only on a risk-versus-benefit basis if the sensor’s performance is to be preserved throughout a conflict’s duration.

Passive direction-finding sensors are confronted by an even steeper obstacle: a non-cooperative vessel can strictly inhibit its telltale emissions or can radiate deceptive emissions. Nor can electro-optical and infrared sensors overcome the remote sensing problem, as their spectral bands render them highly inefficient for wide-area searches, drastically limit their effective range, and leave them susceptible to natural as well as man-made obscurants.[iv]

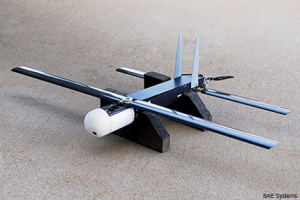

If a prospective attacker possesses enough ordnance or is not cowed by the political-diplomatic risks of misidentification, he might not care to confidently classify a contact before striking it. On the other hand, if the prospective attacker is constrained by the need to ensure his precious advanced weapons inventories (and their launching platforms) are not prematurely depleted, or if he is constrained by a desire to avoid inadvertent escalation, remote sensing alone will not suffice for weapons-targeting.[v] Just as was the case with Soviet maritime bombers, a relatively risk-intolerant prospective attacker would be compelled to rely upon close-in (and likely visual) classification of targets following their remote detection. This dependency expands a defender’s space for layering its anti-scouting defenses, and suggests that standoff-range attacks cued by sensor-to-shooter networks will depend heavily upon penetrating (if not persistent) scouts that are either highly survivable (e.g., submarines and low-observable aircraft) or relatively expendable (e.g., unmanned system ‘swarms’ or sacrificial manned assets).

On the expendable scout side, an advanced weapon (whether a traditional missile or an unmanned vehicle swarm) could conceivably provide reconnaissance support for other weapons within a raid, such as by exposing itself to early detection and neutralization by the defender in order to provide its compatriots with an actionable targeting picture via a data link. An advanced weapon might alternatively be connected by data link to a human controller who views the weapon’s onboard sensor data to designate targets for it or other weapons in the raid, or who otherwise determines whether the target selected by the weapon is valid. While these approaches can help improve a weapon’s ability to correctly discriminate valid targets, they will nevertheless still lead to ordnance waste if the salvo is directed against a decoy group containing no targets of value. Likewise, as all sensor types can be blinded or deceived, a defender’s ability to thoroughly inflict either outcome upon a scout weapon’s sensor package—or a human controller—could leave an attacker little better off than if its weapons lacked data link capabilities in the first place.

We should additionally bear in mind that the advanced multi-band sensors and external communications capabilities necessary for a weapon to serve as a scout would be neither cheap nor quickly producible. As a result, an attacker would likely possess a finite inventory of these weapons that would need to be carefully managed throughout a conflict’s duration. Incorporation of highly-directional all-weather communications capabilities in a weapon to minimize its data link vulnerabilities would increase the weapon’s relative expense (with further impact to its inventory size). It might also affect the weapon’s physical size and power requirements on the margins depending upon the distance data link transmissions had to cover. An alternative reliance upon omni-directional LPI data link communications would run the same risk of eventual detection and exploitation over time we previously noted for active sensors. All told, the attacker’s opportunity costs for expending advanced weapons with one or more of the aforementioned capabilities at a given time would never be zero.[vi] A scout weapon therefore could conceivably be less expendable than an unarmed unmanned scout vehicle depending upon the relative costs and inventory sizes of both.

The use of networked wide-area sensing to directly support employment of long-range weapons could be quite successful in the absence of vigorous cyber-electromagnetic (and kinetic) opposition performed by thoroughly trained and conditioned personnel. The wicked, exploitable problems of contact classification and identification are not minor, though, and it is extraordinarily unlikely any sensor-to-shooter concept will perform as advertised if it inadequately confronts them. After all, the cyclical struggle between sensors and countermeasures is as old as war itself. Any advances in one are eventually balanced by advances in the other; the key questions are which one holds the upper hand at any given time, and how long that advantage can endure against a sophisticated and adaptive opponent.

In part three of the series, we will consider how a force network’s operational geometry impacts its defensibility. We will also explore the implications of a network’s capabilities for graceful degradation. Read Part Three here.

Jon Solomon is a Senior Systems and Technology Analyst at Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. in Alexandria, VA. He can be reached at jfsolo107@gmail.com. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and are presented in his personal capacity on his own initiative. They do not reflect the official positions of Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. and to the author’s knowledge do not reflect the policies or positions of the U.S. Department of Defense, any U.S. armed service, or any other U.S. Government agency. These views have not been coordinated with, and are not offered in the interest of, Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. or any of its customers.

[i] David S. Alberts, John J. Garstka, and Frederick P. Stein. Network Centric Warfare: Developing and Leveraging Information Superiority, 2nd Ed. (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense C4ISR Cooperative Research Program, August 1999), 32-34, 103-105, 250-265.

[ii] For some observations on the idea of network-enhanced systems, see Owen R. Cote, Jr. “The Future of Naval Aviation.” (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Security Studies Program, 2006), 28, 59.

[iii] Solomon, “Defending the Fleet,” 39-78. For more details on Soviet anti-ship raiders dependencies upon visual-range (sacrificial) scouts, see Maksim Y. Tokarev. “Kamikazes: The Soviet Legacy.” Naval War College Review 67, No. 1 (Winter 2013): 71, 73-74, 77, 79-80.

[iv] See 1. Jonathan F. Solomon. “Maritime Deception and Concealment: Concepts for Defeating Wide-Area Oceanic Surveillance-Reconnaissance-Strike Networks.” Naval War College Review 66, No. 4 (Autumn 2013): 88-94; 2. Norman Friedman. Seapower and Space: From the Dawn of the Missile Age to Net-Centric Warfare. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2000), 365-366.

[v] Solomon, “Defending the Fleet,” 94-96.

[vi] Solomon, “Maritime Deception and Concealment,” 95.