Read Part One of this two-part series here.

By Jason Lancaster

Action

“The Action Phase is the period from the arrival of the amphibious force in the operational area, through the accomplishment of the mission and the termination of the amphibious operation.” –JP 3-02

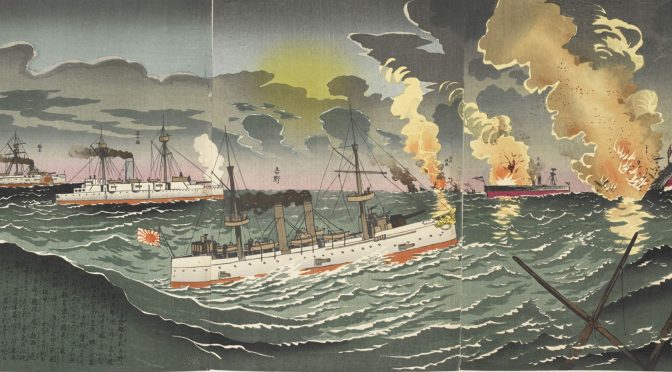

At 2 am, 5,500 troops climbed down into their boats to begin the assault on the French-held Aboukir Peninsula in 1801. Some of the boats had to row six miles to form up, delaying the assault from dawn until almost 9 am. As the boats approached the beach they could see the French troops and artillery in the sand dunes to their front, and artillery from the fort to their right started to fire. Embarked in one of the boats for the assault was Lieutenant Aeneas Anderson who stated, “Never was there a more trying moment.” As the troops crammed into the heavily loaded landing craft were vulnerable to fire the French managed to sink several craft. Some of the men in the boats were killed by round shot or drowning, while many were rescued from the water by boats tasked with SAR.1 Naval gunfire support was provided by Royal Navy bomb vessels Tartarus and Fury, two gunboats, and three armed launches.2 These vessels took station on the flanks and supported the landings by attacking Aboukir Castle on the right flank.

As the initial wave landed they formed up in the water. Soldiers of the 40th and 23rd Regiments charged ahead to capture the high sand dune in their front. On the left, 200 French cavalry charged the Coldstream Guard still forming up in knee-deep water, but the cavalry were repulsed by a well-timed volley fired by the 48th. The sharp action of twenty minutes secured a British beachhead at Aboukir. In a span of 5 minutes the British had landed 5,000 troops and formed for battle on a beach. After 15 minutes the British had driven off entrenched French forces and captured six cannons.3

British casualties had been heavy. Out of an initial landing force of 5,000, the Royal Navy had lost 97 officers and men killed or wounded, while the army had lost 625 killed, wounded, or missing and presumed drowned.4 Despite the heavy losses, British morale soared. General Menou had so doubted the ability of the British to establish a beachhead that he had only sent a detachment of 2,000 to defend against the landing instead of a larger force. French prisoners stated, “They had no fear that a landing could succeed.”5 General Menou expected the French army would have to fight on three fronts in Egypt. The army continued to fight a numerically superior yet qualitatively inferior Ottoman army east of Suez. The French expected this British force to land somewhere near Alexandria, and for another British force from India to land somewhere on the Red Sea coast. The British exploited Lake Aboukir and Aboukir Bay as a highway transporting water, supplies, and armed launches to provide naval gunfire support to the forward edge of battle. With the beachhead secured, General Abercromby’s forces advanced from Aboukir toward Alexandria.

On the 13th of March, the French attacked the British at Mandara, but well-positioned British troops repulsed the French. After two British victories, the local Arabs began to sell provisions to the army, reducing the reliance on provisions provided from the ships.6

On the 21st of March the French attacked again. General Abercrombie, leader of the British expeditionary force, was mortally wounded in the battle and died aboard the flagship instructing his staff to return the soldier’s blanket he was carried to the ship in. The French retired into the city of Alexandria. The British then left a force to besiege the city while another force pressed up the Nile to capture Cairo and link up with soldiers from India. On 16 August, Captain Cochrane and General Coote executed a second landing west of Alexandria to completely surround the city. On 29 August, 1801, General Menou’s besieged army surrendered.

Command and Control

Modern U.S. amphibious doctrine supports a Commander, Amphibious Task Force (CATF) and a Commander, Landing Force. Both commanders will draft an establishing directive to outline priorities and define who will be the supported and supporting commander throughout the phases of the operation. Throughout an amphibious operation the supported commander will change based on what is going on. For example, during an amphibious assault, the CATF will remain the supported commander until the CLF has established a defensible beachhead ashore.7 The CLF will then assume the role of supported commander and the CATF will continue to support, typically with logistics until relieved.

Throughout this campaign, there was less CATF/CLF coordination than desired. The first objective of the expedition was to capture the Spanish fleet at anchor in Cadiz. Despite both commanders’ amphibious experience the objective was not met. Lord Keith dithered over whether to support the landings or not, and he “could not be answerable for the winds.”8 If winds were from the southwest the fleet would be scattered. Unlike in modern doctrine where the CATF is the supported commander until the CLF has a defendable beachhead, Lord Keith felt his duty and responsibility done once the fleet was anchored in the correct operational area. This lack of interest meant that on the scheduled day of the landings there was both a shortage of landing craft and massive confusion when those craft did not go to the correct ships to pick up troops. Eventually, the decision was made to cancel those landings.9

The day after the landings were scheduled to happen, the southwest winds blew the fleet off Cadiz. If the landing force had been caught half ashore and half at sea, the landing force ashore would have been destroyed and the Egyptian campaign possibly never would have commenced. The lack of proper planning, of rehearsals, and Lord Keith’s continued unwillingness to make a decision about the landing created great tension between the army and the navy. Resentment among the army was so high that General Abercromby wrote to Secretary Dundas. Lord Keith received a letter from the First Sea Lord suggesting he remain in Gibraltar, and let another admiral oversee the Egyptian expedition.10 Good natured General Abercromby understood that part of his role as CLF was to calm the waters between the landing force and the naval force to ensure unity of effort. Today, the CATF and CLF embark aboard the same ship, however General Abercromby and Lord Keith were embarked on separate ships, and the First Sea Lord insinuated that this was the cause of tension between the two. Space aboard ship was the likely culprit in why the two commanders were embarked separately.

Lord Keith’s top priority was the location of the French fleet, and whether the French Navy would attempt to disrupt the landings. This question caused real problems for Lord Keith. The risk was real as Lord Nelson won the battle of Aboukir Bay in 1798 when a large portion of the French crews had been ashore. The army required over half the sailors in the fleet to support their operations ashore, and the transports would be so undermanned as to be unable to work the ships while the boat crews were away. 3,339 sailors served in Lord Keith’s fleet; 545 of those sailors were expected to serve ashore, and a further 820 were expected to serve in the boats ferrying supplies to the army.11 Aboukir Bay provided an anchorage, but it was no safe haven in a storm. Lack of sailors also increased the risk of shipwrecks in storms and defeat in battle if the French fleet appeared. With the ships half-manned, Lord Keith doubted that in a crisis those sailors could rejoin the fleet prior to an engagement with the French. Lord Keith wrote, “I am convinced that were I to withdraw a man, the troops would re-embark and charge the failure to me.” Despite Lord Keith’s misgivings, fleet support ashore enabled British victory.

Conclusion

This campaign provides an excellent study of the difficulties of planning an amphibious operation. One will never have all the intelligence desired and one will have to make decisions based off very incomplete or inaccurate data. In London, poor intelligence and an ill-defined mission risked the expedition before it even set sail. At sea and on land the British forces demonstrated their resolve and flexibility in overcoming adversity and the French to secure Egypt. The seven weeks spent training while waiting for Ottoman support demonstrated the importance of rehearsals in preparation for an amphibious assault. The confusion of the Cadiz expedition was replaced with calm, discipline, and order. The daily training in ship-to-shore movement and forming lines from landing craft enabled the landing force to conduct an opposed landing against entrenched infantry utilizing linear musket-age tactics.

Throughout the campaign the Royal Navy provided naval fire support and logistics support to the army. Fleet support enabled the execution of the campaign, but the most important asset the expedition had was General Abercromby. His attention to detail, emphasis on training, and tactful ability to work with Lord Keith, despite the Admiral’s foibles, ensured the successful execution of the campaign.

LT Jason Lancaster is a U.S. Navy Surface Warfare Officer. He is currently the Weapons Officer aboard USS STOUT (DDG 55). He holds a Masters degree in History from the University of Tulsa. His views are his alone and do not represent the stance of any U.S. government department or agency.

References

[1] Anderson, pg 222.

[2] Thomas Walsh andW.W. Knollys, The Cockade in the Sand,(Leonaur, 2014), pg 62.

[3] Anderson, pg 223.

[4] Mackesy, 75

[5] Lowry, pg 72

[6] Anderson, pg 239.

[7] Joint Publication 3-02 Amphibious Operations, pp II-3

[8] Moore, 375

[9] Ibid., pp 376-378.

[10] Creswell, pg 99.

[11] Mackesy, pg 46.

Bibliography

Anderson, Aeneas. Journal of the Forces which sailed from the Downs on a Secret Expedition. London: Wilson and Co. of the Oriental Press, 1802.

Bartlett, Merrill L., ed. Assault From the Sea: Essays on the History of Amphibious Warfare. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1983.

Faden, William. “A detail of a plan of the Operations of the British Forces in Egypt from the landing in Aboukir Bay on th 8th of March to the Battle of Alexandria March 21st inclusive.” Wikimedia Commons. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Mandora#/media/File:Faden_1801_alexandria_battle_detail.jpg. London, 1801.

Fortescue, J. W. A History of the British Army. Vol. IV. London: Macmillan and Co. Limited, 1915.

Glover, Richard. Peninsular Preparation 1795-1809. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1963.

Joint Publication 3-02 Amphibious Operations. Washington DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2014.

Life of Sir R. Abercromby. Liverpool: J. Fowler, Market Place, Ormskirk, 1806.

Loutherbourg, Philip James de. “The landing of British troops at Aboukir, 8 March 1801.” Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_landing_of_British_troops_at_Aboukir,_8_March_1801.jpg. London, n.d.

Lowry, James. Fiddlers and Whores: The Candid Memoirs of a Surgeon in Nelson’s Fleet. Edited by John Millyard. London: Chatham Publishing, 2006.

Mackesy, Piers. British Victory in Egypt The End of Napoleon’s Conquest. London: Tauris Parke, 2010.

Moiret, Joseph-Marie. Memoirs of Napoleon’s Egyptian Expedition 1798-1801. Edited by Rosemary Brindle. Translated by Rosemary Brindle. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001.

Molyneaux, Thomas More. Conjunct expeditions: or expeditions that have been carried on jointly by the fleet and army. London: ECCO Print Editions, 1759.

Moore, John. The Diary of Sir John Moore. Edited by J.F. Maurice. II vols. London: Edward Arnold, 1904.

Porter, Robert Ker. A Correct Account of the Battle of Alexandria. New York: Southwick and Hardcastle, 1804.

Walsh, Thomas, and W. W. Knollys. The Cockade in the Sand: The Defeat of Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign. Leonaur, 2014.

Wilson, Sir Robert Thomas. Narrative of the British Expedition to Egypt. Dublin: W. Corbett, 1803.

Featured Image: Brigade of Guards Landing at Aboukir, March 8, 1801. Thomas Luny, 1759-1837.