By Jason Lancaster

Introduction

“Amphibious Warfare requires the closest practicable cooperation by all the combatant services both in planning and execution, and a command organization which definitely assigns responsibility for major decisions throughout all stages of the operation.”– Admiral Henry K. Hewitt, USN1

By late 1800, the French Revolution was going poorly for the British. Britain’s economy was in distress, her allies had been driven from the war, Russia was shifting to support France, and neutral Baltic nations were arming to enforce their maritime rights and neutrality. Yet despite all this Britain fought on alone against France.

British armed forces were a tale of two branches. The Royal Navy had cleared the seas of French warships, blockaded the coasts of France, and was well respected. By way of contrast, the British Army had performed poorly ashore in northern Europe, had suffered catastrophic casualties while campaigning in the West Indies, and was universally derided by other European armies.2 Britain needed a military victory to solidify the government’s political position at home and abroad as well as to demonstrate the capability of the newly reformed British Army. The British amphibious operation in Egypt was what the nation needed.

Since July 1798, French forces had occupied Egypt. In August 1798, Nelson’s fleet obliterated the French fleet, cutting the French army off from France. After a year of campaigning in Egypt and Syria, Napoleon returned to France. Yet, the French army remained in Egypt, a permanent threat to British India. Britain needed a victory on land to secure room for negotiations at the expected peace conference.

The British joint campaign in Egypt has languished in relative obscurity, overshadowed by Admiral Nelson’s epic naval battle in 1798. When viewed through U.S. Joint Publication 3-02 Amphibious Operations, this campaign provides several lessons on the successful conduct of an amphibious operation.

Despite the successful execution of the landing and British victory in the campaign, mistakes made by the national command authority, in intelligence, logistics, planning, and the relationship between the commanding general and admiral caused problems throughout the operation. Even though U.S. amphibious doctrine was developed and refined in the Second World War era and Joint Publication 3-02 is the evolution of those experiences, this essay argues that the principles of a successful amphibious campaign as defined by JP 3-02 are applicable regardless of time period and this historic case study can be analyzed through this doctrine.

Planning

“The planning phase normally denotes the period extending from the issuance of an initiating directive that triggers planning for a specific operation and ends with the embarkation of landing forces. However, planning is continuous throughout the operation.” – JP 3-02 3

British politicians agreed that they needed a victory, but where Britain should strike was a matter of debate. The Prime Minister and cabinet debated whether to support another royalist uprising in France, another landing in Holland, Egypt, or somewhere else.4 Surprisingly, despite Britain’s recent support of failed French royalist uprisings and landings in Holland both options were initially more popular than Egypt.

Secretary of State for War Sir Henry Dundas spent years improving Britain’s position in India, and did not want French interference to threaten his work. Secretary Dundas and Napoleon agreed Egypt was the key to India. The French Consul in Egypt stated 10,000 French troops could proceed down the Red Sea to India and take Bengal from the British in one campaign. In London, intelligence on French force levels in Egypt were scarce, but estimates were 13,000 French troops demoralized and crippled by the plague. Intelligence Reports stated the garrison of Alexandria numbered 3,000, and scattered through Upper Egypt and Syria were 10,000 more French troops. 5 In reality, the French army in Egypt was closer to 25,000 soldiers, and despite sacrifices and hardship, their morale was high.6 Britain planned to send an army of 15,000 to Egypt.7 Britain also planned to send an additional 3,000 troops from India, but there was little likelihood of coordination between the two forces, and a failed landing would have enabled the French to defeat both forces piecemeal. This faulty intelligence could have proved disastrous to the landing force. British diplomats in Constantinople also believed they had coordinated Ottoman logistical support for horses and gunboats.

Secretary Dundas, turned to his fellow Scot, General Sir Ralph Abercromby, to lead the expedition and turn the tide of the war. General Abercromby was an experienced general who had successfully conducted several amphibious operations in the West Indies earlier in the war. At 65, he was an innovative soldier despite his age who mixed the best of the American light infantry and Prussian close order drill schools of British military thought. His protégé, another Scot, General Sir John Moore, pioneered British light infantry tactics, and had served with General Abercromby throughout the West Indian campaigns seizing sugar islands from the French. He served as a division commander throughout this campaign and represented the army’s interests in planning the ship-to-shore movements of the campaign.8

The naval leadership was no less capable and distinguished. Admiral George Elphinstone, 1st Viscount Keith, successfully negotiated with the mutineers at the Nore in 1798. He served as deputy Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean under Admiral Lord St Vincent before himself assuming the command in November 1799. Lord Keith experienced amphibious operations during the siege of Charleston in the American Revolution and in 1795, an expedition that captured the Dutch Cape Colony. Lord Keith’s deputy for planning the ship to shore movement was Captain Alexander Cochrane, uncle of Admiral Lord Thomas Cochrane and a distinguished future admiral in his own right. He had served on the American station during the Revolutionary War and was commanding officer of HMS Ajax, a 74-gun ship of the line.

“The focus of the planning process is to link the employment of the amphibious force to the attainment of operational and strategic objectives.”9 Initially clear direction for operational and strategic objectives was not given. Campaigns in the Netherlands, France, and Egypt were proposed. Finally, Secretary Dundas tasked General Abercromby and Lord Keith to conduct a landing in Egypt. Secretary Dundas gave the commanders four objectives: eject French forces, restore Ottoman rule in Egypt, protect British interests in India, and secure a better negotiating position for a future peace conference. Secretary Dundas directed the joint force to attempt to seize the Spanish Fleet at anchor in Cadiz before proceeding to Marmorice Bay to receive promised logistical support from the Ottoman Empire and then to defeat the French forces in Egypt accomplish British objectives.

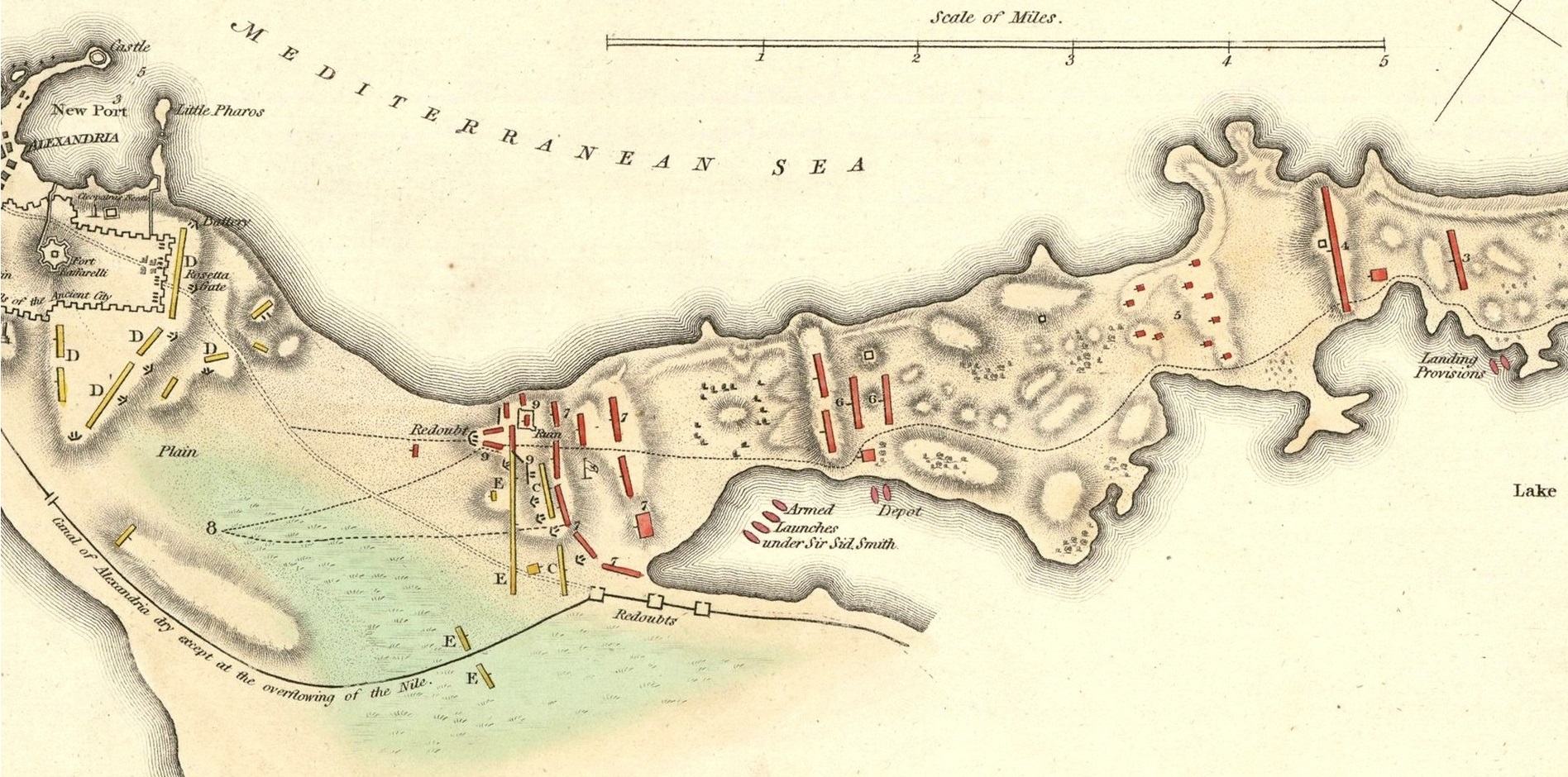

Operational planning for the expedition began when General Abercromby arrived in Gibraltar. According to JP 3-02, top down planning, unity of effort, and integrated planning are the key components of the planning phase. General Abercromby’s presence in the planning was keenly felt, however Lord Keith displayed little interest in the planning. General Abercromby spoke with naval officers who had served on the Egyptian coast. These conversations helped shape the campaign and narrow the landing sites to the Aboukir Peninsula or Rosetta. Aboukir would enable the British fleet to provide logistical support and the army’s flanks would be protected by water during the advance on Alexandria. A landing at Rosetta would enable the British army to link up with the Ottoman army and advance together toward the French.10

Initial reports led General Abercromby to believe that his army would find potable water on the Aboukir Peninsula. Eventually, General Abercromby learned through captured letters that all water would have to come from the amphibious shipping. During a council of war aboard HMS Foudroyant naval officers familiar with the coast explained, “when anchored in Aboukir Bay, [the fleet] would be able to land a sufficient quantity of water and provisions for the army.” As the army advanced, “it would always be within a mile of [the coast], boats with water and provisions might attend.”11 If the fleet was destroyed in battle or forced off station by gales, “the army would die of thirst.” While the force was anchored in Marmorice Bay, General Moore was sent to Syria to speak with Captain Sir Sydney Smith RN, serving with the Ottoman forces fighting the French. General Moore assessed the Ottoman forces as disorganized, poorly trained, and disease-ridden. General Abercromby selected Aboukir for the landing site. The condition of the Ottoman army played a major role in that decision. Despite the water supply risk, Aboukir Peninsula was closer to Alexandria, and the waters of the bay and lake protected the army’s flanks from French cavalry.12

Embarkation

“The embarkation phase is the period during which the landing force with its equipment and supplies embark in assigned shipping.” – JP 3-02

Despite almost a decade of war, in 1801, the British army remained small. To create an expedition of 15,000 troops involved redeploying from British deployments around Great Britain, Ireland, and Europe. Not all regiments in the British Army were designated for service outside Europe. Some regiments, particularly militia regiments, were able to volunteer for active service, but only in Europe. High casualty rates in the West Indies meant that few militia regiments volunteered to serve outside Europe. British troops embarked from Ireland and Britain, including units who would not participate in the campaign, but would relieve units in Gibraltar and Minorca that would participate in the campaign.13 The complex embarkation plan shuffled soldiers across Europe, resulted in some soldiers spending months cramped inside troopships waiting to get ashore.

The expeditionary force also lacked cavalry mounts. British forces often deployed without horses and purchased them locally since horses take up a large amount of space aboard ships and there was a great difficulty keeping horses healthy for long voyages. The Ottoman Empire promised the British army an ample supply of horses. In reality, British diplomats and supply officers were unable to procure a sufficient number of quality mounts for the cavalry, artillery, and wagon train. The horses provided proved to be subpar, and the strongest horses were given to the artillery to pull cannons. The poor quality mounts meant that the French cavalry would outclass the British cavalry in Egypt.14

Rehearsal

“The rehearsal phase is the period during which the prospective operation is rehearsed to: test the adequacy of plans, timing of detailed operations, and combat readiness of participating forces; provide time for all echelons to become familiar with plans; and test all communications and information systems.” – JP 3-02

The British attempt to land a force to seize the Spanish Fleet at Cadiz was a fiasco. A large portion of that was because there had been no time for a rehearsal. Boats went to the wrong transport, it took hours for soldiers to embark the boats, and then they did not form up properly. The landing was called off and the following day a storm scattered the fleet, and the invasion of Cadiz was over. When the fleet arrived in Marmorice, they planned to spend just a few days to rendezvous with Ottoman naval forces and supplies before proceeding to Egypt. Instead, the expected logistical support from the Ottomans never materialized and the expedition spent almost two months waiting.15 General Abercromby used this time to good effect drilling his troops. This time enabled the force to learn and rehearse their ship-to-shore movement to great effect. For seven weeks, the troops practiced ship-to-shore movements, boats going to the right transport, soldiers embarking the boats, boats forming waves, and soldiers forming line of battle from the boats.

The boats were organized into three waves. The first wave comprised 58 flatboats. Each flatboat carried 50 soldiers. The second wave encompassed 81 cutters and the third wave comprised 37 launches. Artillery in boats followed in the fourth wave, the cannons would be disembarked and crewed by sailors.16 The troops practiced disembarking from ships into the landing craft and forming into line of battle on the beach. The soldiers were instructed to enter the flatboats as expeditiously as possible, sit down, and keep their muskets unloaded until formed into line on the beach. Officers’ servants were instructed to bear arms in the ranks and to carry no more than their own equipage.17 The boat crews practiced maintaining the assault boat spacing of 50 feet and the movement from ship-to-shore.18

Movement

“The movement phase is the period during which various elements of the amphibious force move from the points of embarkation or from a forward deployed position to the operational area.” – JP 3-02

The expedition’s movement phase consisted of three phases. Phase 1 consisted of the movement from Great Britain and Ireland to Gibraltar and Minorca where the forces were gathering. This phase included the failed attempt to seize the Spanish fleet at Cadiz.

Phase 2 consisted of the movement from Gibraltar and Minorca to Marmorice Bay. Following the Cadiz debacle, the expedition watered and victualed in Africa, and proceeded to Marmorice Bay, Turkey. During this phase a terrible storm scattered the fleet and several days were spent bringing the transports back to the fleet.19 After several weeks, the fleet arrived in Marmorice Bay, whose deep waters and high cliffs proved an excellent anchorage.

Phase 3 was the movement from Marmorice Bay to Egypt. The expedition encountered a storm that frightened the Turkish gunboats, which left the expedition. On 1 March, the expedition arrived off Alexandria – sailing in so close that the masts of the French ships in harbor were visible – and proceeded down the coast to Aboukir; however, weather conditions prevented the landings until the 8th of March.20 This alerted the French, gave General Menou eight days to concentrate troops and entrench them on Aboukir Peninsula. While French troops were rushed to the scene, including 2,000 soldiers to Aboukir Peninsula, there was confusion in the French army as Captain Moiret described, “various movements so numerous as to be impossible – as well as pointless.”21

Now that the expedition was off the coast, the Royal Engineers conducted a beach reconnaissance. Unfortunately, the good works of Majors Fletcher and Mackerras was to no avail. Major Fletcher was captured and Major Mackerras was killed by artillery during their reconnaissance. When the fleet arrived, General Abercromby undertook the reconnaissance himself.22

LT Jason Lancaster is a U.S. Navy Surface Warfare Officer. He is currently the Weapons Officer aboard USS STOUT (DDG 55). He holds a Masters degree in History from the University of Tulsa. His views are his alone and do not represent the stance of any U.S. government department or agency.

References

[1] Joint Publication 3-02: Amphibious Operations, 18 July 2014, pg II-1

[2] Michael Glover, Peninsular Preparations, (Cambridge, 1963),pg 3.

[3] Joint Publication 3-02 Amphibious Operations, (2014), I-7

[4] (Mackesy 2010, 5)

[5] John Fortescue, A History of the British Army Vol. IV, (MacMillan, 1915), pg 800.

[6] Joseph –Marie Moiret, Memoirs of Napoleon’s Egyptian Expedition, 1798-1801, (Green Hill, 2001), pg 160.

[7] Piers Mackesy British Victory in Egypt, (TPP 2010), pg 13.

[8] Piers Mackesy British Victory in Egypt, (TPP 2010), pg 14.

[9] JP 3-02, pg III-2.

[10] John Moore, The Diary of Sir John Moore, (Arnold, 1904), pp 397-398.

[11] Moore, 397.

[12] Fortescue, pg 809.

[13] Fortescue pg 804.

[14] Mackesy, pg 100.

[15] James Lowry, Fiddlers and Whores, (Chatham, 2006), pg 59.

[16] John Creswell, Generals and Admirals, (Longman’s, 1952), pg 101

[17] Aeneas Anderson, Journal Of the Forces, ( Debrett, 1802), pg 201.

[18] Moore, pg 399.

[19] Lowry, pg 59.

[20] Lowry, pp 70-71.

[21] Moiret, pg 161.

[22] Anderson, pp 213-215.

Featured Image: British Troops Landing at Aboukir by Philip James de Loutherbourg (Wikimedia Commons)