By Dmitry Filipoff

CIMSEC had the opportunity to discuss with Admiral James Stavridis (ret.) his latest book, Sailing True North: Ten Admirals and the Voyage of Character. In this book Adm. Stavridis profiles ten historical admirals, revealing their character traits, leadership skills, and what their life accomplishments can teach modern Sailors and society.

Q: From Fisher to Zumwalt, Rickover, and Hopper, you profile trailblazing admirals who built their legacies on innovation and reform. What can these leaders teach us about driving change into large organizations, and how to manage the risk that comes with innovating?

JS: Most of the admirals profiled in Sailing True North were innovators to one degree or another, but especially Fisher, Rickover, Zumwalt, and Hopper. As Steven Jobs of Apple said, “The difference between leaders and followers is innovation.” And it is worth observing that the innovations developed by these trailblazers were at times successful, and at other times ended in failure. But each of their stories as innovators had several common attributes. Indeed, the three key lessons for anyone seeking to move truly big organizations through successful innovation come from “the inside out.” First, building consensus from within; then obtaining committed support from outside the organization; and stubborn persistence. Achieving all of these requires an inner strength of character and deep self confidence.

Admiral Zumwalt was a “shock to the system” of the Navy and never slowed down to bring the organization along. While some of his initiatives survived his tenure (notably real progress on race relations), many of them failed – from very youthful commanding officers to beards for Sailors. I too learned the hard way that if you want to change an organization, it is necessary but not sufficient to have a big idea. When I took over at U.S. Southern Command, I wanted to change the focus of the military combatant command from a warfighting entity to an interagency structure optimized for the soft power missions of South America and the Caribbean. But I failed to build an internal consensus on the change, largely through overconfidence that my idea was so brilliant that everyone would simply fall in line. I was able to ram the changes through, but the next commander simply reversed course. So the first lesson in innovation is laying out a coherent case and building internal support.

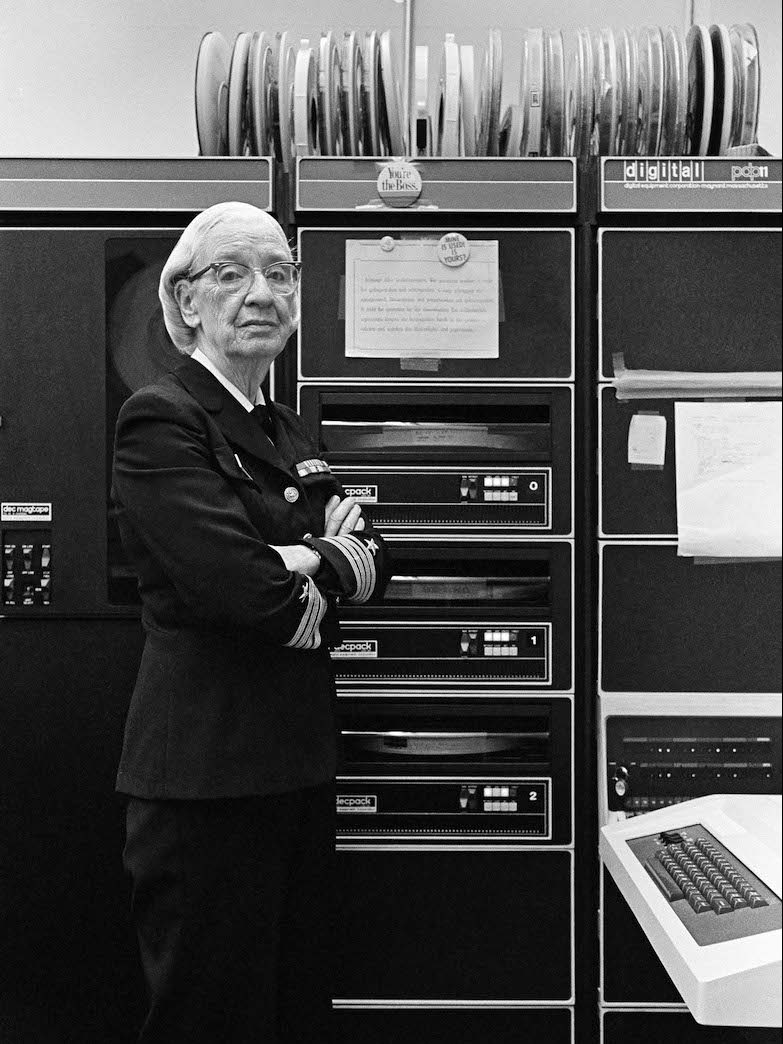

The second key is getting outside support. When Grace Hopper wanted to bring the Navy into the computer age, she worked hard at connecting the chain of command with new technologies. She went on the road endlessly talking about computing and innovation as the keys for the Navy to move forward. Inspiring change requires not only support and buy-in within the organizational lines, but also convincing external stakeholders to move forward as well. Personally, I truly learned this while as the supreme allied commander at NATO, where we needed all 28 nations to move forward in consensus to make change – so I spent an inordinate amount of time on the road convincing European leaders to make necessary changes in our operations, from the Balkans to Afghanistan to counter-piracy.

Third and finally, stubborn persistence is almost always necessary. The world hates change, and as a general rule, three out of four innovative ideas will fail. Taking no for an answer is not an option if you truly believe in the importance of the outcome. Admiral Sir Jackie Fisher was a deeply committed innovator, but frequently his ideas were rejected for lack of resources, professional jealousy, or fear of change. Yet he pounded away year after year and decade after decade and wrenched the Royal Navy into the 20th century – with fast capital ships, submarines, gunnery improvements, and many personnel changes. When I led the Navy’s innovation think tank, Deep Blue, in the days after 9/11, we failed on many ideas – but some vital ones emerged and changed the way the Navy fought in the Global War on Terror.

Inspiring change – the heart of innovation – is in the end a challenge of character. To make others leap into the unknown with you requires not only a brilliant idea, but the inner self-confidence that others admire.

Q: When it comes to Admirals Nimitz, Nelson, and also Themistocles, these leaders are remembered for earning decisive success in conflict. What can we learn from these leaders on what it takes to be a successful wartime commander?

JS: The warfighting Admirals Themistocles, Nelson, and Nimitz all faced extreme existential levels of combat – they literally carried the future of their countries on the decisions they made.

First, each was a shrewd judge of subordinates, selecting the right commanders, then giving them plenty of leeway when it came to actual combat. And each was skilled at building operational and tactical teams that could work seamlessly on the vast battlespace of the world’s oceans. Of note, Nelson’s “band of brothers” never required elaborate battle plans of detailed instructions, nor did the subordinate admirals of WWII or the galley captains of the Battle of Salamis.

Second, each of the three set the values of their nation ahead of their own agendas. In terms of their inner character, each burned with zeal for their homeland, and were willing to make extreme personal sacrifices to succeed.

Third, all were masters of the technology of the day in terms of understanding what we would call the “kill chain” in today’s world. They mastered their craft coming up and were able to use all of the combat tools at their disposal.

And finally, each of the three were strategically minded, highly aware of the interconnection of the individual battles and campaigns they led to the “larger picture” of the global conflicts each faced – Themistocles with Persia, Nelson with Bonaparte’s France, and Nimitz with the Japanese Empire.

All of these come from qualities of inner character, of course. To know others, you must be aware of your own inner set of values. Patriotism and a willingness to be part of something far larger than yourself is crucial, as is the discipline and diligence to master the technology of the time. And the quality of strategic thinking is one that is honed through reading, study, and practice. Each of these admirals – none of them perfect, by the way – had all four of those qualities.

Q: For Zheng He and Sir Francis Drake, these leaders traveled far from home on uncertain voyages, and their superiors afforded them a great degree of discretion to act as they saw fit. What can be learned from how these leaders skillfully managed the independence of command?

JS: Even across the great distance of centuries, both Zheng He and Drake stand out in their ability to lead into the unknown. Yet they used a very different set of tools to do so, reflecting their highly different backgrounds and character. Zheng He, a eunuch and courtier as well as a warrior, was a skilled bureaucrat who could marshall significant resources to build overwhelming fleets. His inner character was one of sacrifice and seeking to gain glory for his master, the Han emperor. Drake, on the other hand, was an angry, brutal leader who used the lash, harsh punishment, executions alongside a reward system built around theft and plunder.

What they shared in common was a driving, energetic personality; strong physical stature; and above all personal courage. To lead into extreme danger and the unknown requires inner energy and self-confidence that can be instantly intuited by a crew. Both of these admiral had those qualities in abundance.

Q: This book was not written strictly for a military audience, because as you write in the introduction, “I am also motivated by a growing sense in this postmodern era that we are witnessing the slow death of character…” Of the many qualities and virtues of these admirals, which do you think both today’s U.S. Navy and society writ large need the most?

JS: Above all, the intertwined qualities of humility, empathy, and listening are fading in many of our leaders across the political spectrum. The relentless pounding of tweets, blogs, Instagram posts, and the deluge of transmission shortens attention spans and reduces our ability to thoughtfully process what we hear. Too many have their transmit side set to max, and their receive side turned off. Character is about quiet self-confidence which allows us to listen to our friends and our critics as well. These are vital in both the military world and civilian life. Not all of the admirals in Sailing True North were humble and empathetic, and often when they stumbled it was for a lack of humility. There is a powerful lesson in that.

Honesty is also a character quality increasingly diminished in a world that seems to shrug off lies, half-truths, and exaggerations with a cynical comment and a knowing look. So often, we see people providing the “easy wrong” answer instead of the “hard right” one. Some of the admirals in the book played it loose with the truth from time to time, but all were at heart unafraid of the truth and wielded it with great effect at crucial moments of decision. We live in an utterly transparent world, and in the end the truth will come out. We need to pay more attention to veracity.

Lastly, I worry that in an age of accelerating technology, we are not innovating fast enough. Advances in artificial intelligence, machine learning, materials, nano-technology, and above all synthetic biology are merging. Can we move fast enough – both inside the military and in the larger civilian world – to keep up? So innovation, a deeply seated quality of character, is vital.

Q: None of the admirals in the book are by any means perfect individuals. Which of their flaws and faults did you find to be the more fascinating?

JS: The anger of Admiral Rickover fascinates me. Having encountered it personally several times (not pleasantly), I feared him. Yet his driven, intense personality also created a kind of cult of admiration among many. I entitled the chapter of the section about him, “The Master of Anger,” and I don’t know if it was something he used consciously or it was merely who he was. In today’s world, we would see many aspects of the “toxic leader” in Rickover, yet the results he delivered and the deep affection he inspired in many contradict that assessment.

Certainly Sir Francis Drake – a killer (both of his own men and victims in his raids) is a bundle of contradictions. His harsh treatment of pretty much anyone he encountered achieved a level of brutality we can only glimpse across the centuries. But he helped defeat the Spanish Armada and achieved great results for queen and country. Another very contradictory personality, with both flaws and virtues.

And Jackie Fisher’s towering ego can be maddening to encounter. He had to be the center of everything, his ideas were always right, and he brooked no interference in his schemes, ever. He must have been a wildly annoying contemporary in the admiralty. But he delivered enormous reform to the Royal Navy and did it all with a certain charm – he was a famous ballroom dancer and was in a passionate marriage.

Q: Throughout the book you relate your personal experiences, whether being a seaborne commander or an officer on staff duty in the halls of the Pentagon. You candidly reflect on past mistakes and flaws, but how did you see yourself grow as a leader over the course of your career?

JS: I started out, like many junior officers, with a lot of arrogance about my own skills. It took me a long time to find balance between self-confidence and over-confidence. My peers, especially my naval academy classmates, helped me with that. Over time, I became a better and more humble person. A big part of that was simply growing older, having children, meeting failure along the voyage, and other natural events.

Also, speaking of balance, I have struggled to find the right balance between career and family. David Brooks, in his marvelous book, The Road to Character, speaks about the difference between our “resume values” (Annapolis grad, Phd, 4-star admiral, NATO commander) and our “eulogy values” (good father, loving brother, best husband). I could do better on those eulogy values in terms of the time I devote – I remain very driven on the professional side. But that is the beauty of the human condition, right?

In the end, we get to choose how we want to approach the world, knowing that our small voyages are so often going to end up sailing against the wind. There is immense comfort in understanding that the value of the voyage will be in seeing that beautiful ocean, and knowing that when we look at it, we see not only vast expanses of salt water, but eternity itself. That voyage for me continues, and I try hard every day to keep sailing as close to true north as I can.

Admiral James Stavridis is an operating executive at The Carlyle Group and Chair of the Board of Counselors at McLarty Associates. A retired 4-star, he led the NATO Alliance in global operations (2009 to 2013) as Supreme Allied Commander, focused on Afghanistan, Libya, the Balkans, Syria, counter-piracy, and cyber security. Earlier, he was Commander U.S. Southern Command (2006-2009) responsible for Latin America. He has more than 50 medals, 28 from foreign nations.

In 2016, he was vetted for Vice President by Hillary Clinton and subsequently invited to Trump Tower to discuss a cabinet position in the Trump Administration.

Admiral Stavridis holds a PhD in international relations and has published nine books and hundreds of articles in leading journals. His 2012 TED talk on global security has over one million views. Admiral Stavridis is a monthly columnist for TIME Magazine and Chief International Security Analyst for NBC News, and has tens of thousands of connections on the social networks.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Contact him at Content@cimsec.org.

Featured Image: Chief of Naval Operations Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz at his desk in the Navy Department. (Naval History and Heritage Command Photo #80-G-K-9334)