By LCDR Jason Lancaster, USN

Introduction

Today the U.S. faces renewed global competition, and conventional and asymmetric naval threats. The future U.S. way of war must innovate beyond the Second World War strategy of out-producing adversaries, since the U.S. has fewer shipyards and its rivals may have greater industrial capacity. Luckily, U.S. history offers examples of the U.S. as both a dominant power as well as an underdog. The Confederate States Navy provides an excellent example of an under-industrialized innovative underdog struggling to defend itself against an industrial juggernaut.

Naval Asymmetries in the U.S. Civil War

During the “War Between the States,” also known as the American Civil War, the Union Navy held as close to permanent general sea control for the duration; but the Confederate Navy waged an effective campaign to deny sea control in the littorals of key port cities. Maritime strategist and theorist Julian Corbett divided the concept of sea control between local or general, temporary or permanent. Sea control means controlling the sea lines of communications (SLOCs) one side needs to maintain while fighting to deny that control to the adversary. One does not need to control the sea to deny it to an adversary. Sea control does not mean that the enemy will not be able to raid SLOCs, but rather those raids will not have a decisive impact on the war.1

The Confederate Navy is considered a failure by popular belief because the Southern fleet was unable to break the Union blockade. The navy designed by Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory was not built to break the blockade, but for “desperate and unequal battle to protect land against sea.”2 This battle began poorly. The Union Navy waltzed into Port Royal, South Carolina, steamed past the Confederate guns at Fort Hatteras, and took control of the North Carolina sounds. Both ports were defended by guns that were out-ranged by the Union Navy.

The Confederate Navy needed a new plan, and with limited resources only a few places could be adequately defended. Secretary Mallory and General Robert E. Lee compiled a list of priority ports. Union leaders of the Blockade Board did the same. Interestingly, both concurred that the key Southern ports were Norfolk-Richmond, Wilmington, Charleston, Savannah, Mobile, New Orleans, and Galveston.

In order to defend these ports Secretary Mallory focused his limited resources on denying sea control by increasing the survivability of warships through iron armor and improved anti-access weapons such as accurate long-range artillery and mines. When established together, this Confederate three-pronged approach successfully defended key Confederate ports. The new Confederate Navy was built to deny sea control near key Confederate ports to enable blockade runners to continue to supply the South, so that the army could continue to resist ashore. Charleston, Wilmington, and Richmond were not conquered by naval invasion but rather fell to the Union army advancing from the rear or, like Mobile, required weakening the Union blockade of Charleston to mass the forces required to invade. This trident approach enabled the South to maintain local sea control in the vicinity of key ports to keep those ports open.3

The theory was that mines and narrow channels limited the maneuverability and fighting effectiveness of ships operating in littoral waters. Well-placed minefields forced ships within range of coastal defense artillery which increased the accuracy and damage of the Confederate Brooke rifles.4 Damaged vessels that got past the mines and coastal defense artillery would have to face the ironclads. This system successfully defended Charleston, Wilmington, and Richmond.

However, the Battle of Mobile Bay demonstrated the inherent weakness of the system. The bold and innovative Union commander Admiral Farragut was not deterred by the mines. He placed anchor chains along his ships’ sides as improvised armor and steamed past the forts with their heavy guns to swiftly attack the single heavily outnumbered ironclad. CSS Tennessee’s steering system was outside the protective armor. Once the steering chains had been shot away, Tennessee was unable to maneuver and was overwhelmed by superior numbers.5

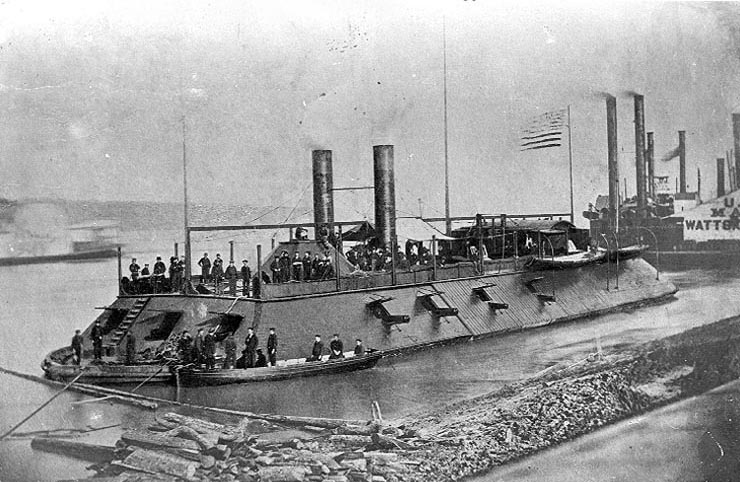

Ironclads

From the beginning, it was clear that the South was at a distinct disadvantage in terms of shipbuilding. With little maritime tradition, few shipyards, and a meager industrial base she could not out-build the Union. Secretary Mallory knew ironclads were the answer. Before the Confederate capital had even moved to Richmond, Secretary Mallory was planning an ironclad navy. On April 26, 1861, Secretary Mallory wrote to the chairman of the House Committee on Naval Affairs:

“I regard the possession of an iron-armored ship as a matter of the first necessity… Inequality of numbers may be compensated by invulnerability; and thus not only does economy but naval success dictate the wisdom and expediency of fighting with iron against wood, without regard to first cost.”6

In Norfolk, Lieutenant John M. Brooke and Chief Naval Constructor John Porter cooperated on a design for a casemate ironclad built on the hull of the frigate Merrimack. With modifications, the basic design became the standard for Confederate ironclads. Richmond and Charleston each completed three ironclads, along the rivers of North Carolina, four were completed, and Savannah and Mobile each completed one. More ironclads were under construction along the Mississippi and other cities. But construction was hampered by material shortages and transportation issues. Throughout the war, 50 ironclads were laid down and 22 of them were commissioned.

However, most Confederate ironclads had maneuverability issues resulting from under-powered engines and deep drafts. Engineering plants were under-powered because the South lacked the capability and expertise to build new plants and used whatever old systems could be salvaged.7

Congressional appropriations and civic societies, including women’s ironclad societies, raised money in major cities to support construction of ironclads like CSS Chicora and Palmetto State in Charleston. Both congress and the citizenry had an expectation that the ironclads would go to sea and break the blockade. Congressional pressure often forced untimely offensives that resulted in disaster. For example, CSS Atlanta was captured by Union forces after she sortied from Savannah in an ill-advised attempt to break the blockade of Savannah against the recommendation of her captain. She ran aground at low tide in the river and was forced to capitulate.

In Charleston, Chicora and Palmetto State conducted a sortie to attack the inshore blockading squadron. They damaged USS Mercidta and USS Keystone State. The Union blockading fleet abandoned the inshore blockade for several weeks until it became clear the two ironclads would not continue patrolling offshore.8

In North Carolina, the Albemarle sailed into the sound and sank the Miami and Southfield, and took part in the liberation of the cities of Plymouth and Washington. She was supposed to rendezvous with the Neuse to support the Confederate Army’s attack on New Bern, but was delayed. The Albemarle struck such fear into the Union fleet that they abandoned the North Carolina sounds. Albemarle was eventually sunk by Union Lieutenant William Cushing in a daring raid up the Roanoke River. Lieutenant Cushing used a steam launch equipped with a spar torpedo to destroy the ironclad.9

Richmond demonstrated the effectiveness of the fleet-in–being, behind obstructions, mines, and powerful artillery. The large Union fleet could not force the obstructions. In January 1865, Secretary Mallory wrote to Captain John Mitchell, commander of the James River Squadron, “If we can block the river at or below City Point, Grant might be compelled to evacuate his position.”10 On January 23-24, 1865, the Confederate fleet sortied, while Union ironclads of the James River Squadron were hundreds of miles away attacking Wilmington. This attack was defeated by the shallow depth of the James River and the Confederate commander’s caution. After a series of groundings, the Confederate fleet returned to its defenses. General Grant understood how close the Confederate Navy had come to raising the siege of Petersburg. If a Confederate ironclad got to City Point, it could destroy the Union supply ships that supported the Union Army besieging Petersburg. Despite frantic telegraphs, the Union James River Squadron did not steam to support the Union batteries. General Grant was lucky that Captain Mitchell had been spooked by the groundings and worried about the impacts of losing his fleet on the defense of Richmond.11

Coastal Defense Artillery

The War Between the States is often used as a demonstration that the adage, “a ship’s a fool to fight a fort” was dead. It was assumed that advances in naval artillery meant that the ship would always win. If one examined the first few disasters of the war, this might be the case. Bold Union attacks in Hatteras, North Carolina, Port Royal, South Carolina, and Galveston, Texas showed the weakness of Confederate artillery early in the war. The Confederacy needed heavy guns. In addition to his work on the Virginia, Lieutenant John M. Brooke also developed a new artillery piece, the 6.4 inch Brooke Rifled Gun, which was outfitted on the Virginia for its contest with Monitor. The Union Parrot Rifled Gun had a single reinforcing iron band around the breech, but the Brooke Rifle had multiple reinforcing iron bands increasing the strength of the gun and enabling it to use more powder to give projectiles greater range.12 The 7 inch Brooke Rifle’s maximum-range of 7,900 yards easily out-sticked the range of Union Parrot Rifles and Dahlgren guns.13 In addition to developing this new gun, Lieutenant Brooke also developed new bolts to fire from the guns. On 26 October 1862, he wrote in his journal that one of these new bolts pierced three two-inch plates and cracked the wood backing.14 These new guns would play a decisive role in preventing the Union Navy from repeating the easy victories of 1862.

While Lieutenant Brooke developed the Brooke Rifle, Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones was tasked with the manufacturing. In Selma, Alabama, the Confederate Navy created a foundry to turn out these guns. Through their resourcefulness, a successful, efficient foundry was created from nothing. Throughout the war, over 70 Brooke Rifles were cast in Selma and an almost equal number cast at Tredegar Ironworks in Richmond. These guns were vital to Secretary Mallory’s layered defense of Southern ports and armed both the forts and ironclads.

Norfolk was captured after Union troops landed near modern day Chix Beach far from Confederate defenses. Local Confederate leadership panicked as Union troops advanced on Norfolk. Unable to evacuate CSS Virginia, the Confederate Navy blew her up to prevent capture.

The road to Richmond seemed open. In May 1862, the Union Navy attempted to steam up the James River to capture the city. The Union force had two non-ironclad ships and three ironclads: USS Monitor, USS Naugatuck, and USS Galena. They were surprised by the Brooke Rifles at Drewry’s Bluff that caused massive damage to Galena and Monitor. Galena was hit over 45 times and was badly damaged, including suffering 25 casualties. The guns at Drewry’s Bluff bought time for the Confederate Navy to obstruct the river with mines and ironclads. The James River defenses would not be challenged again until 1865.15

In March 1863, Union Admiral Farragut attempted to run up river past the guns of Port Hudson on the Mississippi with his fleet of seven non-ironclad ships. Restricted room to maneuver, the strong current, and heavy Confederate shore-based gunfire caused havoc in the Union fleet. Only two of Admiral Farragut’s ships succeeded in passing the batteries. Every ship ran aground at some point in the engagement. Admiral Farragut’s ships were lashed together in pairs to minimize the risk of ships being disabled by gunfire and left to their own devices. USS Hartford and USS Albatross led the fleet upriver and were the only two ships to reach their objective. The second pair ran aground, and the shock of the grounding broke them loose of each other, damaging their engines and causing them to drift down river. Shot from the batteries damaged the boilers on USS Richmond, while her partner, USS Genesee, couldn’t make headway against the current and drifted down river. The lone ship in the rear, USS Mississippi caught fire after being hit with heated shot that exploded when the fire reached her magazines.16 In April 1863, Admiral DuPont attempted to force his way past the forts and batteries of Charleston with a fleet of ironclads. After several hours of bombardment, he failed. His force sustained massive damage. Three ironclads were put out of action for weeks, and one, USS Keokuk, sank from damage sustained during the fight.17

These guns not only heavily damaged ships that tried to force the passage, but their large range kept the blockading ships at bay, increasing the ability of blockade runners to enter the port. Wilmington’s geography provides an excellent example of the impact of heavy guns. Fort Fisher was constructed of sand at the tip of Cape Fear, protecting the two inlets into the Cape Fear River. Because of the distance between the two inlets, the Union Navy had to blockade both entrances which required more ships. The heavy guns of Fort Fisher included a 150 pound Armstrong gun, Blakely and Brooke rifles, eight and ten-inch Columbiads, and several 32 pounders. The 150 pound Armstrong gun and Brooke Rifles out-ranged the weapons of the blockading fleet by over a mile, forcing the ships farther offshore and increasing the number of successful blockade runners.18

Mine Warfare

Admiral Farragut’s famous quip to, “damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead” may be considered rash. He lost one of his ironclads, USS Tecumseh to Confederate mines (which were known as torpedoes at the time) at Mobile. If the mines had not become waterlogged, he might have lost more ships. Throughout the war, Confederate mines sank 29 Union ships and damaged 14 more.19

Mines struck fear into the hearts of Union sailors and impacted operations for commanders less daring than Admiral Farragut. Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury and Brigadier General Gabriel Rains led the Navy and Army torpedo research and production teams. Commander Maury’s experiences as a scientist and with electricity and transatlantic telegraph cable led to the development of the electrically detonated underwater mine. General Rains’ experience came from creating landmines and explosive booby traps during the Seminole Wars. While mines were a success, they were not perfect. Confederate manufacturing and new technology meant many became waterlogged duds and did not detonate, saving many more Union ships from a watery grave.

Mines were a controversial weapon in the 1860s; many thought mines lacked chivalry. Admiral Farragut said, “Torpedoes are not so agreeable when used by both sides; therefore, I have reluctantly brought myself to it. I have always deemed it unworthy of a chivalrous nation, but it does not do to give your enemy such a decided superiority over you.” Confederate Secretary of War George Randolph thought they should be used as a means to defend rivers and ports, but not just to kill the enemy. The Confederate Navy created offensive mines called the spar torpedo, a mine attached to a pole controlled from a ship.

The CSS Hunley, one of the world’s first submarines, and the first to sink an enemy vessel in combat, sank the USS Houstonatonic on blockade duty off Charleston in 1864. In addition to submarines, the Confederates developed the David-class torpedo launch. They were not true submarines, but their low profile made them challenging to spot at night. Throughout 1863, CSS David conducted attacks on USS New Ironsides, Wabash, and Memphis. The submarines and torpedo launches forced the Union blockade to remain farther offshore from Charleston to minimize the risk of submerged torpedo attack.

Mines were effective by striking fear into the hearts of sailors and shaping the battlespace through deterrence. The presence of mines often persuaded Union admirals to not attack, earning effective sea denial for the Confederacy. Admiral Farragut’s famous line stands out because most admirals did not go full speed ahead – they stopped and sent boats to sweep for mines first or simply remained offshore.

Conclusion

Secretary Mallory’s Navy succeeded in its desperate struggle to defend land against sea. The Confederate trident approach succeeded at denying the Union Navy local sea control in the vicinity of key port cities and forced ships to often remain farther from the coast. The Confederate layered defenses enabled Confederate ports to remain open until the final collapse of the Confederacy.

Despite an ever tightening blockade, the port of Wilmington blockade runners brought 3.5 million pounds of meat, 1.5 million pounds of lead, 2 million pounds of saltpeter, 500,000 pairs of shoes, 300,000 blankets, 50,000 rifles, and 43 cannon from Europe in the latter half of 1864. The Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of Tennessee received new uniforms and equipment that enabled them to continue the struggle. Fort Fisher, the gateway to Wilmington, was captured in January 1865 after two amphibious landings. The Army of Northern Virginia capitulated four months later.20

Today, the U.S. Navy is the largest in the world. However, it finds itself in another technological revolution similar to the rise of the ironclad. While it has the ships and assumes it has permanent sea control, rivals have heavily invested in the spiritual successor to the Brookes Rifle, the anti-ship cruise missile.

The U.S. Navy must learn from the Confederate example and create its own trident of technologies and tactics to out-compete rival advances. The U.S. Navy should rapidly construct new long range anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs) that out-range opponents, improve and revive mine-warfare forces, and think hard about what evolution flows from the modern range and defense of the aircraft carrier. In addition, these advances should be shared with allies, such as Japan and the Philippines, who could utilize new American-developed sea mines and ASCMs to deny an adversary sea control near their littorals. Mobile long-range ASCM batteries on the islands of Luzon and Palawan could close the entire South China Sea to an adversary, much like Russian coastal defense cruise missile sites in Crimea can contest much of the Black Sea.

Great power rivals understand that a fleet-on-fleet engagement against the U.S. Navy is incredibly risky and have developed alternatives, just like the Confederate Navy developed alternatives to a fleet-on-fleet engagement with the Union. Now it is the U.S. Navy’s turn to learn from history, and develop its own counter-punch to ensure it maintains permanent sea control and open sea lines of communication.

LCDR Jason Lancaster is an alumnus of Mary Washington College and has an MA from the University of Tulsa. He is currently serving as the N8 Tactical Development Officer at Commander, Destroyer Squadron 26. His views are his own and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Navy or Department of Defense.

Endnotes

1. Corbett, Julian, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy, pp 125-127.

2. Luraghi, Raimondo, A History of the Confederate Navy, pg 4.

3. Simson, Jay, Naval Strategies of the Civil War, pp 129-131.

4. Ibid. pg 131.

5. Still, William N. Jr, Iron Afloat: The Story of the Confederate Armorclads, pg 210.

6. Ibid, pg 10.

7. Sims, pp 227-228.

8. Browning, Robert M. Jr, Success is all that was expected: The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War, pp 137-140.

9. Still, pp 212-213.

10. Coski, John M., Capital Navy, The Men, Ships, and Operations of the James River Squadron, pg 196.

11.Ibid, pp 202-205.

12. Brooke, George, Ironclads and Big Guns of the Confederacy, pg 127.

13. Drury, Ian and Gibbons, Tony, The Civil War Military Machine, pp 77-80.

14. Brooke, pg 115.

15. Coski, pg 46.

16. Page, Dave, Ships Versus Shore: Civil War Engagements along Southern Shores and Rivers, pp 316-319.

17. Browning, pg 140.

18. Drury, pp 79-82.

19. http://www.navalunderseamuseum.org/civilwarmines/ accessed 15 April 2019.

20. Stephen R. Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy (Columbia, University of South Carolina Press, 1988), pg 1.

Extended Bibliography

Coski, John M. Capital Navy: The Men, Ships, and Operations of the James River Squadron. New York: Savas Beatie, 2005.

Gibbons, Ian Drury & Tony. The Civil War Military Machine. New York: Smithmark, 1993.

Jr, George M. Brooke. Ironclads and Big Guns of the Confederacy: The Journal and Letters of John M. Brooke. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2002.

Jr, Robert M. Browning. From Cape Charles to Cape Fear: The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron During the Civil War. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1993.

—. Success is All That Was Expected: The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War. Washington DC: Potomac Books, inc, 2002.

Jr, William N. Still. Iron Afloat The Story of the Confederate Ironclads. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1985.

Luraghi, Raimondo. A History of the Confederate Navy. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1996.

Page, Dave. Ships versus Shore: Civil War Engagements Along Southern Shores and Rivers. Nashville: Rutledge Hill Press, 1994.

Simson, Jay W. Naval Strategies of the Civil War. Nashville: Cumberland House Publishing inc, 2001.

United States Naval Undersea Warfare Museum. http://www.navalunderseamuseum.org/civilwarmines/. 2019. http://www.navalunderseamuseum.org/civilwarmines/ (accessed April 15, 2019).

Waters, W. Davis. Gabriel Rains and the Confederate Torpedo Bureau. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2014.

Wise, Stephen R. Lifeline of the Confederacy Blockade Running During the Civil War. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1988.