It is surprising that in the fine group of “personal theory of power” essays CIMSEC ran jointly with The Bridge May-June, no author selected strategic geography as a subject source. Despite advances from steam power to cyber communications that have reduced the relative size of the world, large geographic obstacles like the Hindu Kush mountain range in Afghanistan and vast empty space of the Indian Ocean continue to cause trouble for even the most powerful states.

Geopolitical theorists from Sir Halford Mackinder to journalist Robert Kaplan have warned of the pitfalls of ignoring geography in strategic calculations and estimates of national power. Successful great powers always included strategic geography in their deliberations up through and including the period of the Second World War. The advent of a muscular and well resourced Cold War, buttressed by an arsenal of advanced nuclear and conventional weapons convinced many U.S. decision-makers that strategic geography was a concept of the 19th rather than the 20th century. The Kennedy administration completed this break with the past in its implementation of the doctrine of “Flexible Response” as the cornerstone of U.S. strategic thought. As stated in Kennedy’s inaugural speech, the United States would employ its vast technological and financial resources to “support any friend” and “oppose any foe” regardless of geographic relationship to U.S. strategic interests. Despite the debacle of the Vietnam War, the U.S. was largely able to continue this policy until the very recent past.

Now, a combination of decreasing military budgets, a smaller armed force, and public disinterest in supporting causes not directly tied to U.S. interests demands that the U.S. return to a rigorous practice of geopolitical calculation. It must exercise discipline in determining how, where and when to commit military forces in defense of national interest. The examples of Afghanistan and the Indian Ocean demonstrate the fundamental limits geography can impose on national power. They also illustrate an important law in geostrategic analysis. A nation may overcome geographic barriers like the Hindu Kush or the Indian Ocean, but such an achievement requires technological and financial commitment. If such effort is not sustained, geographic limitations will again impose their effects.

Now, a combination of decreasing military budgets, a smaller armed force, and public disinterest in supporting causes not directly tied to U.S. interests demands that the U.S. return to a rigorous practice of geopolitical calculation. It must exercise discipline in determining how, where and when to commit military forces in defense of national interest. The examples of Afghanistan and the Indian Ocean demonstrate the fundamental limits geography can impose on national power. They also illustrate an important law in geostrategic analysis. A nation may overcome geographic barriers like the Hindu Kush or the Indian Ocean, but such an achievement requires technological and financial commitment. If such effort is not sustained, geographic limitations will again impose their effects.

The cases of conflicts in Afghanistan and control of the Indian Ocean over history illustrate the limits geography exposes on national power. Isolated by a series of geographic barriers including the Hindu Kush mountain range, Afghanistan remains a remote location. Its unique series of mountain passes in key locations has drawn Eurasian conquerers from the dawn of history. These men and their armies came not so much to capture Afghanistan, but rather to control these mountain passes that form a virtual “roundabout” for transiting in and around Central Asia. Control of Afghanistan throughout history has meant easy access to Iran, the Indian subcontinent and northern Central Asia.

Afghanistan’s false reputation as a “graveyard of empire” comes not so much from it’s inhabitants who seem to habitually resist any attempts at outside control, but rather the problem of maintaining a large force in such a remote region. Western armies from Alexander the Great to the present U.S. and NATO force in the country have had to create a long, tortuous, and expensive supply line into or though Afghanistan in order to sustain their military operations there or in adjacent lands. Alexander, British imperial forces in three wars, and now American and NATO forces have always crushed Afghan resistance and have been able to maintain a reasonable amount of control within the region. They have departed only when deprived of the economic support that provides the technological edge to their warfighting and logistics capabilities. A nation can maintain an army of many thousands in Afghanistan, provided that power or group of powers is willing to fly in supplies or negotiate their delivery through unfriendly states over long and difficult overland routes. Now that financial support for the technological effort necessary to sustain a large Western force in Afghanistan is failing, the limits of geography are again re-imposing themselves on the remote Central Asian region.

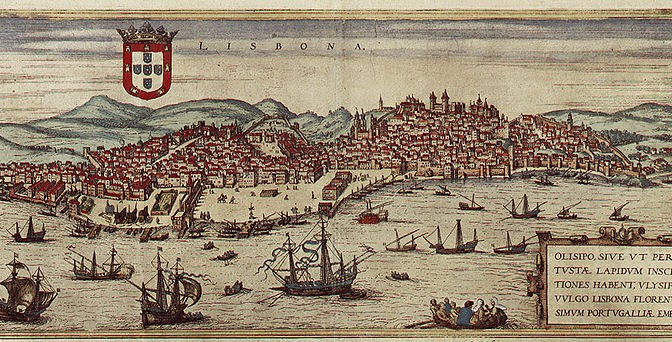

The Indian Ocean has equally proved itself a vast and relatively remote space from the early 1400’s when Chinese Admiral Zheng He sailed its waters seeking trade and building Chinese influence to recent, frustrating efforts to located missing Malaysian Air Flight 370. When the Chinese Ming dynasty decided to forgo further Zheng He voyages in 1424, either for economic reasons, an intensified Mongol threat, or just superstition (the accounts vary), geographic limits returned with later, deadly results for the Chinese empire. Nascent European powers like Portugal, the Netherlands, and the British were able to penetrate and control the Indian Ocean and its key chokepoint connections to the Pacific. In just 200 years, the once omnipotent Chinese Empire found its coastline controlled by powerful European naval forces. The Chinese failure to appreciate the geographic limits of seapower caused the near-dismemberment and wreck of the Chinese state.

The British Empire also lost control of the Indian Ocean when it failed to either fully fund its naval presence there or fully implement a technological solution to mitigate funding shortfalls. A series of Royal Air Force (RAF) facilities, originally conceived to support air policing of imperial holdings became a crucial element of British efforts to control the Indian Ocean in spite of reduced naval expenditures. This network of RAF installations became even more important after the Second World War as the strength of the Royal Navy (RN) plummeted and newer, longer-ranged aircraft could patrol wider areas of ocean, especially when equipped with radar. The British finally abandoned this network of installations in the 1970’s as their naval presence in Singapore came to an end. When this happened, the limits of geography were re-imposed and the Indian Ocean again became a relatively un-patrolled open space. This vacuum of power allowed the Soviet Navy to enter the Indian Ocean with nuclear cruise missile submarines and threaten U.S. forces in transit, as well as Australian interests.

The United States would do well to respect these examples of geographic limits, as significant financial restraints limit future U.S. military efforts. Extreme geographic disadvantage can be overcome by a combination of financial and technological solutions. In the absence of such effort however, geographic limitations again impose effects and limit the exercise of national power. With a shift in U.S. attention to the large Indo-Pacific region, geographic obstacles to the exercise of U.S. power will require innovative, well funded technological solutions. The U.S. must fund these efforts, such as improved unmanned platforms, better offensive and defensive capabilities for naval units and improved space-based surveillance of the region. Neglecting such actions will create significant geographic barriers to the exercise of U.S. national power in the Indo-Pacific region.

Steve Wills is a retired surface warfare officer and a PhD student in military history at Ohio University. His focus areas are modern U.S. naval and military reorganization efforts and British naval strategy and policy from 1889-1941. He posts here at CIMSEC, sailorbob.com and at informationdissemination.org under the pen name of “Lazarus”.

Dean Cheng joins us to discuss China. Like a flourless brownie, this podcast is dense and delicious. We hit China’s goals and perspectives: From the Chinese “status quo”, to the South China Sea, to India, to the use of crises as policy tools. If you want to see behind the headlines, this is your podcast.

Dean Cheng joins us to discuss China. Like a flourless brownie, this podcast is dense and delicious. We hit China’s goals and perspectives: From the Chinese “status quo”, to the South China Sea, to India, to the use of crises as policy tools. If you want to see behind the headlines, this is your podcast.