The following is a two-part series on how the U.S. might better utilize cyberspace and information operations as a Third Offset. Part I will evaluate current offset proposals and explores the strategic context. Part II will provide specific cyber/IO operations and lines of effort.

By Jake Bebber

“It is better by noble boldness to run the risk of being subject to half of the evils we anticipate than to remain in cowardly listlessness for fear of what might happen.”

-Herodotus, The Histories

Introduction

In 2014, then Secretary of Defense Hagel established the Defense Innovation Initiative, better known as the Third Offset, which is charged with recommending ways to sustain American military superiority in the face of growing capabilities fielded by powers such as Russia and China.[i] The purpose of the Third Offset is to “pursue innovative ways to sustain and advance our military superiority” and to “find new and creative ways to sustain, and in some cases expand, our advantages even as we deal with more limited resources.” He pointed to recent historical challenges posed by the Soviets in the 1970’s which led to the development of “networked precision strike, stealth and surveillance for conventional forces.” Centrally-controlled, inefficient Soviet industries could not match the U.S. technological advantage, and their efforts to do so weakened the Soviet economy, contributing to its collapse.

Today, China represents the most significant long-term threat to America and will be the focus here. A number of leading organizations, both within and outside government, have put forward recommendations for a Third Offset. However, these strategies have sought to maintain or widen perceived U.S. advantages in military capabilities rather than target China’s critical vulnerabilities. More importantly, these strategies are predicated on merely affecting China’s decision calculus on whether to use force to achieve its strategic aims – i.e., centered around avoiding war between the U.S. and China. This misunderstands China’s approach and strategy. China seeks to win without fighting, so the real danger is not that America will find itself in a war with China, but that America will find itself the loser without a shot being fired. This paper proposes a Cyberspace-IO Offset strategy directly attacking China’s critical vulnerability: its domestic information control system. By challenging and ultimately holding at risk China’s information control infrastructure, the U.S. can effectively offset China’s advantages and preserve America’s status as the regional security guarantor in Asia.

All effective strategies target the adversary’s center of gravity (COG), or basis of power. “Offset strategies” are those options that are especially efficient because they target an adversary’s critical vulnerabilities, while building on U.S. strengths, to “offset” the opponent’s advantages. Ideally, such strategies are difficult for an adversary to counter because they are constrained by their political system and economy. Today, China’s COG is the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The stability of this system depends greatly on the ability of the Chinese regime to control information both within China, and between China and the outside. Without this control, opposition groups, minority groups, and factions within the CCP itself could organize more effectively and would have greater situational awareness for taking action. Thus, information control is potentially a critical Chinese vulnerability. If the United States can target the ability of the Chinese regime to control information, it could gain an efficient means to offset Chinese power. This offset strategy, using cyberspace and other information operations (IO) capabilities, should aim to counter China during the critical window in the next ten to twenty years when Chinese economic and military power will surge, and then subside as demographic, economic and social factors limit its growth.

Targeting the CCP’s ability to control information can be considered a long-term IO campaign with options to operate across the spectrum of conflict: peacetime diplomacy and battlespace preparation; limited conflict; and, if deterrence fails, full-scale military operations. The goal is to ensure that PRC leaders believe that, as conflict escalates, they will increasingly lose their ability to control information within China and from outside, in part because the U.S. would be prepared to use more drastic measures to impede it.

This strategy is most efficient because it serves as an organizing concept for cyber options targeted against China that would otherwise be developed piecemeal. It could serve as a means to prioritize research and development, and better link military planning for cyberspace operations to public diplomacy, strategic communication, and economic policy initiatives. The nature of cyberspace operations makes it difficult to attribute actions back to the United States with certainty, unless we wish it to be known that the U.S. is conducting this activity. Finally, it provides an alternative array of responses that policy makers can use to offset growing Chinese power without immediate direct military confrontation.

Demographic, economic and social factors will combine to create a ceiling on Chinese power, ultimately causing it to enter a period of decline much sooner than it expects.[ii] These factors will stress the Communist Party’s ability to exclude economic, social and political participation of dissenters, and create further reliance by the Party on information control systems.

The Strategic Environment

The United States is a status quo power. It seeks to retain its position of dominance while realizing that relative to other powers, its position may rise or fall given the circumstances. It supports the post-World War II international order – a mix of international legal and liberal economic arrangements that promote free trade and the resolution of disputes through international organizations or diplomatic engagement when possible. The United States recognizes the growth of China, and that it will soon achieve “great power” status, if not already. It is most advantageous to the United States if the “rise” (or more correctly, return to great power status) of China occurs peacefully, and within the already established framework of international rules, norms, and standards.

There are two important considerations. First is the “singularity” of China with respect to its self-understanding and its role in the world. China views the last two centuries – a time when China was weak internally and under influence from foreign powers – as an aberration in the natural world order. Most Chinese consider their several thousand year history as the story of China occupying the center of the world with “a host of lesser states that imbibed Chinese culture and paid tribute to China’s greatness …” This is the natural order of things. In the West, it was common to refer to China as a “rising power,” but again, this misreads China’s history. China was almost always the dominant power in the Asia-Pacific, punctuated by short periods of turmoil. It just so happened that the birth and growth of the United States took place during one of those periods of Chinese weakness.[iii]

The strategic approach of China is markedly different, based on its concept of shi, or the “strategic configuration of power.” The Chinese “way of war” sees little difference in diplomacy, economics and trade, psychological warfare (or in today’s understanding, “information warfare”) and violent military confrontation. To paraphrase the well-known saying, the acme of strategy is to preserve and protect the vital interests of the state without having to resort to direct conflict while still achieving your strategic purpose. The goal is to build up such a dominant political and psychological position that the outcome becomes a foregone conclusion. This is in contrast to Western thought which emphasizes superior power at a decisive point.[iv]

To the American leadership, the “most dangerous” outcome of a competition with China would seem to be one that leads to war; hence the near-desperate desire to not undertake any action which might lead China down that path. Yet a better understanding of China suggests that it believes it can (and is) achieving its strategic purpose without having to resort to force. Its military buildup, use of economic trade agreements, diplomacy, and domestic social stability are creating the very political and psychological conditions where the use of force becomes unnecessary. China is quite content to remain in “Phase 0” with the United States, because it believes it is winning there. Thus, the question for America is not “How do we maintain the status quo in Phase 0?” but “How do we win in Phase 0?” The most dangerous course of action is not war with China, but losing to China without a shot being fired.

Current Offset Proposals

In response to the call for proposals, a number of initiatives and programs have been put forward by both the Department of Defense and leading national security think tanks. The underlying assumption of most of these proposals is that the United States has lost or is quickly losing its “first mover” advantage – such as that offered by the shift from unguided to guided munitions delivered from a position of stealth or sanctuary. In this regard, China represents a “pacing threat,” leading the way in developing its own guided weapons regime and the ability to deliver them asymmetrically against the United States.[v] In order to regain America’s military advantage, most recommendations follow along these lines:

- Development and procurement of new platforms and technologies that leverage current perceived technological advantages over China in such areas as:

- Unmanned autonomous systems;

- Undersea warfare;

- Extended-range and low-observable air operations;

- Directed energy; and

- Improved power systems and storage.

- New approaches to forward basing, including hardening of infrastructure (both physical and communication networks), the use of denial and deception techniques and active defense;

- Countering China’s threats to U.S. space-based surveillance and command and control systems;

- Assisting allies and friends in the development of or exporting of new technologies that impose smaller-scale anti-access and area denial (A2/AD) costs on China; and

- Reconstitute and reinvigorate Department of Defense “iterative, carefully adjudicated tabletop exercises and model-based campaign assessments.”[vi]

These approaches[vii] may have much to offer and are commendable, however they suffer from a glaring weakness: none target China’s center of gravity or critical vulnerabilities. They seek to leverage capabilities where the United States appears to enjoy an advantage, such as undersea warfare. For example, while it may be true that the People’s Liberation Army-Navy (PLAN) is not as proficient as the U.S. Navy (or some allies) in the undersea domain, it is also true that the Chinese regime is investing heavily to “close the gap” in these and other capabilities or is developing asymmetric alternatives. The United States will face a diminishing marginal utility as it attempts to maintain or widen the gap, especially in an era when China’s cyberspace-enabled information exploitation capabilities are extremely robust, and capable of transferring intellectual property back to China on a scale unimaginable in the Cold War.

More fundamentally, the offsets proposed are not guided by an overarching grand strategy that utilizes all elements of national power attacking key weaknesses and critical vulnerabilities in the Chinese regime, much in the same way that the Reagan Administration was able to do against the Soviets. Reagan’s policy and strategy represented a “sharp break from his predecessors,” eschewing containment in favor of attacking “the domestic sources of Soviet foreign behavior.”[viii] By recognizing the inherent weakness of the Soviet economic system, the new policy sought to leverage national military, political and economic tools to press the American advantage home, causing the Soviet system to collapse. This is not to suggest that the Chinese economic system suffers from the same malaise as their Soviet brethren did. Despite growing demographic, social and economic headwinds, it is unlikely that the United States can “bankrupt” the Chinese. However, China does have acute vulnerabilities – vulnerabilities which align with unique American advantages.

China’s Center of Gravity and Critical Vulnerabilities

None of the proposed previously mentioned offset lines of effort attempt to identify or target China’s COG. The center of gravity is defined by Milan Vego is “a source of massed strength – physical or moral – or a source of leverage whose serious degradation, dislocation, neutralization, or destruction would have the most decisive impact on the enemy’s or one’s own ability to accomplish a given political/military objective.”[ix] Joint military doctrine defines it as “The source of power that provides moral or physical strength, freedom of action, or will to act.”[x] The center of gravity concept is important to offset strategies because it enhances “the chance that one’s sources of power are used in the quickest and most effective way for accomplishing a given political/military objective.” It is the essence of “the proper application of the principles of objective, mass and economy of effort.”[xi]

Using an analytic construct designed by Vego, we note that any military situation encompasses a large number of both “physical and so-called abstract military and nonmilitary elements.” These are the “critical factors” that require attention and are deemed essential to the accomplishment of the objective, both of the adversary and ourselves. Not surprisingly, these factors encompass both critical strengths and critical weaknesses – both of which are essential. Critical vulnerabilities are “those elements of one’s military or nonmilitary sources of power open to enemy attack, control, leverage, or exploitation.” By attacking critical vulnerabilities, we ultimately attack the enemy center of gravity.[xii] The figure below shows notionally how China’s information control systems are a critical vulnerability (note that it is not all-encompassing).

![Figure 2. Notional Center of Gravity Analysis[xiii].](https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/rsz_image_1.png)

A Cyberspace – IO Strategy

China’s regime identifies the free flow of information as an existential threat, and has erected a massive bureaucratic complex to censor and restrict free access to the nearly 618 million (and growing) Chinese internet uses (and 270 million social network users).[xix] However, the very nature of the Internet as a networked system makes censorship and restricted access difficult to maintain. As has been shown, China’s information control systems represent a critical vulnerability to their center of gravity. China’s network security is managed by a fragmented, disjointed system of “frequently overlapping and conflicting administrative bodies and managing organizations.”[xx]

China’s cyberspace operations and strategy are driven primarily by domestic concerns, with its central imperative being the preservation of Communist Party rule. Domestic security, economic growth and modernization, territorial integrity and the potential use of cyberspace for military operations define China’s understanding. Even its diplomatic and international policies are built around giving China maneuvering room to interpret international norms, rules and standards to serve domestic needs, principally through the primacy of state sovereignty. This creates a natural tension, as China must seek to balance economic growth and globalization with maintaining the Party’s firm grip on power. Not only is Internet usage controlled and censored, but it is also a tool for state propaganda.[xxi]

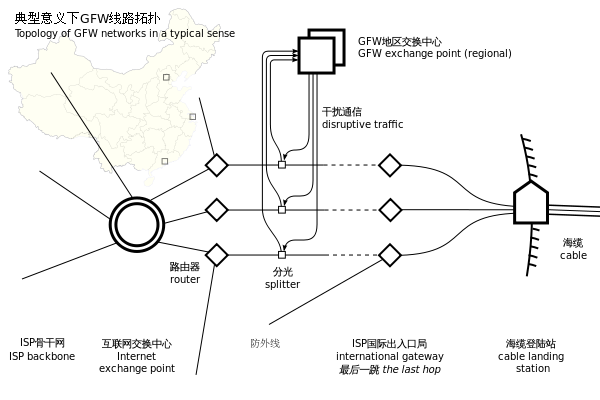

Chinese authorities use a number of techniques to control the flow of information. All internet traffic from the outside world must pass through one of three large computer centers in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou – the so-called “Great Firewall of China.” Inbound traffic can be intercepted and compared to a regularly updated list of forbidden keywords and websites and the data blocked.[xxii] Common censorship tactics[xxiii] include:

- Blocking access to specific Internet Protocol (IP) addresses;

- Domain Name System (DNS) filtering and redirection, preventing the DNS from resolving or returning an incorrect IP address;

- Uniform Resource Locator (URL) filtering, scanning the targeted website for keywords and blocking the site, regardless of the domain name;

- Packet filtering, which terminates Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) transmission when a certain number of censored keywords are detected. This is especially useful against search engine requests.

- “Man-in-the-Middle” attack, allowing a censor to monitor, alter or inject data into a communication channel;

- TCP connection reset, disrupting the communication data link between two points;

- Blocking of Virtual Private Network (VPN) connections; and

- Network Enumeration, which initiates an unsolicited connection to computers (usually in the United States) for the purpose of blocking IP addresses. This is usually targeted against secure network systems or anonymity networks like “Tor.”

China’s information control regime is vulnerable on a number of levels to a coordinated strategy that seeks to hold it at risk. From a technical standpoint, the distributed nature of the internet makes it inherently vulnerable, the “Great Firewall” notwithstanding. The techniques used to filter and block content have a number of workarounds available to the average person. For example, IP addresses that have been blocked may be accessed utilizing a proxy server – an intermediary server that allows the user to bypass computer filters. DNS filtering and redirection can be overcome by modifying the Host file or directly typing in the IP address (64.233.160.99) instead of the domain name (www.google.com). These are simple examples that a novice government censor can easily outwit, but the point remains.

China has long been rightfully accused of being a state-sponsor of cybercrime and theft of intellectual property. One negative consequence of this from China’s perspective is the high level of cybercrime within China “due in large part to rampant use and distribution of pirated technology” which creates vulnerabilities. It is estimated that 54.9 percent of computers in China are infected with viruses, and that 1,367 out of 2,714 government portals examined in 2013 “reported security loopholes.”[xxvi] China’s networks themselves, by virtue of their size and scope, represent a gaping vulnerability.

At the same time, China’s information control bureaucracy is especially unwieldy. This is an ideal target to exploit the seams and gaps both horizontally and vertically in their notoriously byzantine structure. The fourteen agencies that conduct internet monitoring and censorship operations must all compete for resources and the attention of policy makers, leading to organizational conflict and competition. Any strategy should exploit these fissures, complicating China’s ability to control information.

Part 2 will outline several lines of effort the U.S. might pursue to attack China’s critical vulnerabilities in its information control system. It will advance the notion that the full range of American power – overt, covert, diplomatic, economic, information and military – must be coordinated and managed at the national level to wage a successful information operations campaign. Based on America’s past success, the future may be brighter than it first appears. Read Part 2 here.

LT Robert “Jake” Bebber USN is a Cryptologic Warfare Officer assigned to United States Cyber Command. His previous assignments have included serving as an Information Operations officer in Afghanistan, Submarine Direct Support Officer and the Fleet Information Warfare Officer for the U.S. Seventh Fleet. He holds a Ph.D. in Public Policy from the University of Central Florida. His writing has appeared in Proceedings, Parameters, Orbis and elsewhere. He lives in Millersville, Maryland and is supported by his wife, Dana and their two sons, Vincent and Zachary. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Navy or U.S. Cyber Command. He welcomes your comments at jbebber@gmail.com.

[i] Charles Hagel. “The Defense Innovation Initiative .” Memorandum for Deputy Secretary of Defense. Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, November 15, 2014.

[ii] Robert Bebber. “Countersurge: A Better Understanding of the Rise of China and the Goals of U.S. Policy in East Asia.” Orbis 59 no. 1 (2015): 49-61.

[iii] Kissinger, Henry. On China. (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2012).

[iv] David Lai. “Learning from the Stones: A Go Approach to Mastering China’s Strategic Concept, Shi.” U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute. May 1, 2004, accessed Decmeber 26, 2014. http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/display.cfm?pubID=378

[v] Shawn W. Brimley. “The Third Offset Strategy: Security America’s Military-Technical Advantage.” Testimony Before the House Armed Services Committee Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces. Washington, D.C., December 2, 2014.

[vi] David.Ochmanek. “The Role of Maritime and Air Power in the DoD’s Third Offset Strategy.” Testimoney Before the House Armed Services Committee Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces. Washington, D.C., December 2, 2014.

[vii] This list is certainly not exhaustive. For a more thorough review of the ones mentioned, see:. Brimley, Shawn W. “The Third Offset Strategy: Security America’s Military-Technical Advantage.” Testimony Before the House Armed Services Committee Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces. Washington, D.C., December 2, 2014. Martinage, Robert. “Statement Before the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces on the Role of Maritime and Air Power in DoD’s Third Offset Strategy.” Testimony Before the House Armed Services Committee Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces. Washington, D.C., December 2, 2014. Ochmanek, David. “The Role of Maritime and Air Power in the DoD’s Third Offset Strategy.” Testimoney Before the House Armed Services Committee Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces. Washington, D.C., December 2, 2014.

[viii] Thomas G. Mahnken.”The Reagan Administration’s Strategy Toward the Soviet Union.” In Successful Strategies: Triumphing in War and Peace from Antiquity to the Present, by Williamson Murray and Richard Hart Sinnreich. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

[ix] Milan N. Vego. Joint Operational Warfare – Theory and Practice. (Newport, RI: Government Printing Office, 2007) VII-13-29.

[x] Joint Chiefs of Staff. Joint Publication 5-0: Joint Operational Planning. (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 2011).

[xi] Vego, Joint Operational Warfare – Theory and Practice, VII-15

[xii] Ibid, VII-15.

[xiii] Joint Publication 5.0 defines Critical Capability as “A means that is considered a crucial enabler for a center of gravity to function as such and is essential to the accomplishment of the specified or assumed objective(s);” Critical Requirement as “An essential condition, resource, and means for a critical capability to be fully operational;” and Critical Vulnerability as “An aspect of a critical requirement which is deficient or vulnerable to direct or indirect attack that will create decisive or significant effects.”

[xiv] Ben Blanchard and John Ruwich. “China Hikes Defense Budget, To Spend More on Internal Security.” Reuters, March 5, 2013, accessed December 23, 2014.http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/03/05/us-china-parliament-defence-idUSBRE92403620130305

[xv] Michael Martina. “China Withholds Full Domestic Security-Spending Figure.” Reuters, March 4, 2014, accessed September 25, 2015. http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/03/05/us-china-parliament-security-idUSBREA240B720140305

[xvi] Ting Shi and Keith Zhai. “China To Boost Security Spending as Xi Fights Dissent, Terrorism.” Bloomberg News, March 5, 2015 accessed September 25, 2015. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-03-05/china-to-boost-security-spending-as-xi-fights-dissent-terrorism

[xvii] Michael Wines, Sharon LaFraniere, and Jonathan Ansfield. “China’s Censors Tackle and Trip Over the Internet.” The New York Times, April 7, 2010, accessed December 23, 2014.http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/08/world/asia/08censor.html

[xviii] Biena Xu. Media Censorship in China. February 2014, accessed December 23, 2014. http://www.cfr.org/china/media-censorship-china/p11515

[xix] Ibid..

[xx] Amy Chang. Warring State: China’s Cybersecurity Strategy. (Washginton, D.C.: Center for a New American Security, 2014) 12.

[xxi] Rebecca MacKinnon. “Flatter World and Thicker Walls? Blogs, Censorship and Civic Discourse in China.” Public Choice 134 (2008): 31-46.

[xxii] Michael Wines, Sharon LaFraniere, and Jonathan Ansfield. “China’s Censors Tackle and Trip Over the Internet.”

[xxiii] Jonathan Zittrain, and Benjamin Edelman. “Empirical Analysis of Internet Filtering in China.” Harvard Law School Berkman Center for Internet and Society. March 20, 2003, accessed December 23, 2014. http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/filtering/china/

[xxiv] Available at: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=4931595

[xxv] Thomas Lum, Patricia Moloney Figliona, and Matthew C. Weed. China, Internet Freedom, and U.S. Policy. Report for Congress, (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, 2013).

[xxvi] Amy Chang. Warring State: China’s Cybersecurity Strategy. 15.