India’s Role in the Asia-Pacific Topic Week

By Byron Chong

Sino-Indian relations have become increasingly complex in the last few years. Though bilateral trade and cooperation has been growing, relations have been increasingly strained by mutual suspicion and intermittent disputes. Given the huge influence the two Asian giants have over the global strategic environment, a key question that arises will be whether they can maintain a stable relationship amidst their growing distrust.

This paper will analyse their relationship through the perspectives of the three major international relations (IR) theories of realism, liberalism, and constructivism and will be split into two parts. The first will describe the main factors that influence bilateral relations. The second will analyse these factors using the three main IR theories as mentioned. The analysis will show that Sino-Indian relations reflect a peculiar kind of stability: although their relationship will continue to be marked by distrust and intermittent disputes, the risk of escalation to war remains unlikely. In general, Sino-Indian relations are influenced by four factors: (1) their history of enmity; (2) strategic competition; (3) nuclear relations; and (4) trade.

History of Enmity

China and India share a number of similarities. Both take pride in their historical past as ancient civilizations and aspire to great power status. Both have nuclear weapons, fast growing economies, and are currently rising powers[1]. Despite their many similarities, their geographical proximity to each other has inevitably created friction.

Indeed, China and India share a long history of enmity. Between them, they have an ongoing territorial dispute that stretches over 4,057 kilometers. This dispute produced a war in 1962, followed by crises in 1967 and 1986[2]. Throughout the decades, despite repeated attempts to come to an agreement, the demarcation of the Line of Actual Control (LAC) remains highly disputed.

China’s occupation of Tibet since 1950 has been another contentious issue. India’s strategic interests in Tibet as a buffer state led it to support Tibetan rebels fighting Chinese rule in the mid-1950s. The Indian government also allowed the Dalai Lama to form the Tibetan government-in-exile in India to conduct “anti-China activities”[3]. For China, India’s continued support to the Dalai Lama is seen as a sustained attempt to undermine Chinese control over Tibet[4].

Growing disagreements with India eventually pushed China to align itself more closely with Pakistan[5]. It was believed that the two-front threat to India from Pakistan and China would distract India from intervening in Tibet. China has supported Pakistan militarily, first with conventional arms and later with nuclear and missile technology[6]. India’s animosity with Pakistan has produced four wars (1948, 1965, 1971, 1999), repeated border skirmishes, terrorist attacks in India, continued tensions over Kashmir and a wider strategic competition for influence in South Asia[7]. The fact that China continued to support to Pakistan even after a warming of Sino-Indian ties simply perpetuated New Delhi’s distrust of Beijing[8].

Both sides have attempted to repair their relationship with various confidence-building measures (CBMs) like reciprocal state visits, signing of various bilateral agreements, joint military exercises, and strengthening of bilateral trade[9]. However, these CBMs have been undermined by intermittent crises which flare up over the historical disputes including occasional border skirmishes and incursions into each other’s territory[10], the stapling or outright denial of visas to those from the disputed states of Kashmir and Arunachal Pradesh by Chinese immigration[11], visits by the Dalai Lama to Arunachal Pradesh[12], and even alleged Chinese diversion of rivers flowing into India[13].

Strategic Competition

While India and China have previously cooperated on issues like climate change and trade[14], international forums have gradually become a competitive arena for the two, where they have attempted to marginalize or deny access to each other. For instance, in 2008, China tried to oppose the Indo-US deal that would allow the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) to trade nuclear materials with India[15]. Similar ‘Chinese’ roadblocks have been encountered by India at the East Asia Summit (EAS), Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM), Asian Development Bank (ADB), etc. Where India has greater influence, it has similarly tried to restrict Chinese access or influence, such as at the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) and Mekong Ganges Cooperation (MGC) forums[16].

Their competition has also expanded into the maritime sphere. In recent years, China has become increasingly dependent on maritime trade with 82% of its oil imports transiting the Indian Ocean (IO) and the Malacca Straits[17]. Protection of its sea lines of communications (SLOCs) in the IO has become a driving force behind China’s plans for a ‘blue water’ navy with greater power projection capabilities. The Chinese navy has also increased its naval activity in the IO with increased port calls at Karachi, Colombo, Chittagong[18] and anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden[19]. Most worryingly, China has been increasing its political and economic relations with India’s neighbours, raising concerns about a “string of pearls” of potential bases in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Myanmar[20].

This conflicts with India’s aspiration towards strategic leadership in the IO[21]. It sees Chinese presence as an incursion into its strategic backyard and perhaps an attempt at “strategic encirclement”[22]. India has responded in two ways. Firstly, its military has been improving its power projection capabilities with plans to acquire new aircraft carriers, naval aircraft[23], and upgrades to its missile capabilities[24]. Secondly, India has been building strategic and economic partnerships with states in the Western Pacific like Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and most importantly, forging a global partnership with the United States (US). Such agreements have increased India’s presence in East Asia, leading some in Beijing to see this as an attempt to weaken China’s influence in the region and make a ‘counter-encirclement’ attempt[25]. This competitive behaviour in both the international and maritime sphere has led to increased friction and distrust in their relationship.

Such friction has been tempered by a level of restraint on both sides. Despite the many strategic agreements with each other’s neighbours, none of these involve any actual military alliances that may draw them into wider disputes. Both have also resisted deploying a significant naval presence in each other’s strategic sphere, with China limiting its major deployments in the IO to anti-piracy operations, and India avoiding the establishment of a permanent naval presence in the Western Pacific[26].

Nuclear Relations

The nuclear capabilities of both sides demonstrate the existence of mutual hedging strategies. China’s Dongfeng (DF) 31 missiles have the range to hit all parts of India but little of US territory. The basing of medium-range missile systems in Tibet is clearly targeted at India[27]. India in turn, has begun development of an Anti-Missile Defence (AMD) system and longer range missiles such as the Agni-III, which has been called “China-specific”[28].

While such hedging strategies could potentially drive rapid armament leading to instability, this likelihood is tempered by ‘escalation-resistant’ policies of both sides. Both adhere to minimalist nuclear doctrines, preferring relatively small numbers of weapons and platforms. While China maintains a numerically larger and more sophisticated arsenal, India has not shown any interest in closing this gap. This acceptance of ‘unequal’ capabilities reduces the possibility of an escalatory nuclear arms race[29]. Moreover, despite the intermittent friction in their relationship, none of their disputes have ever had a nuclear element to them[30].

Trade

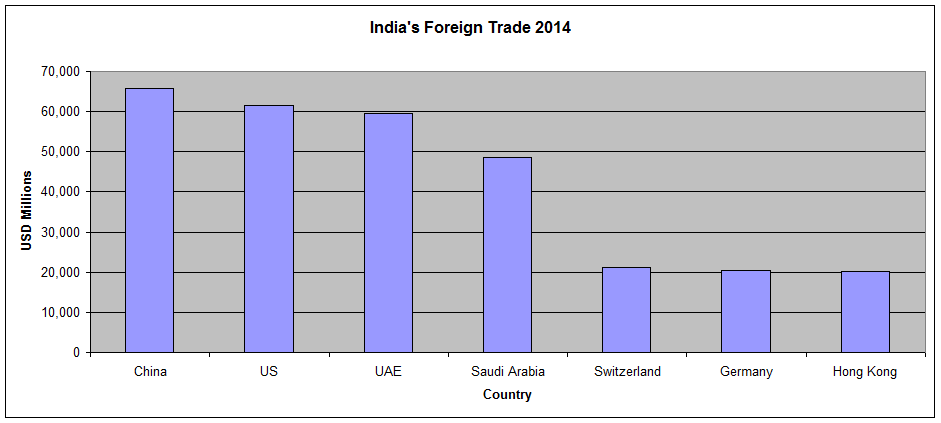

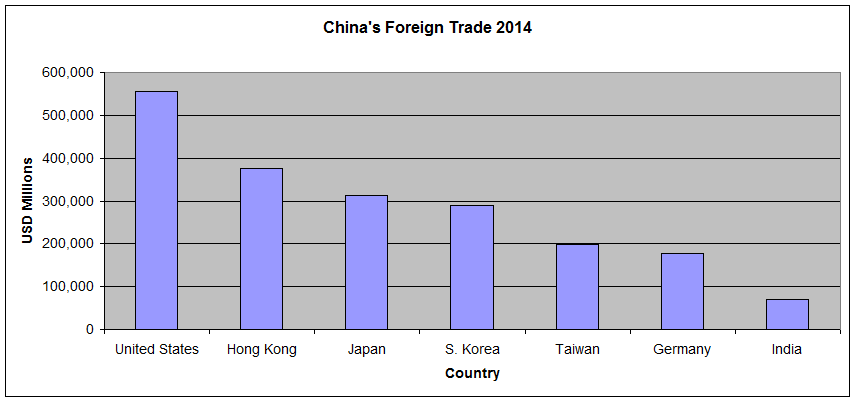

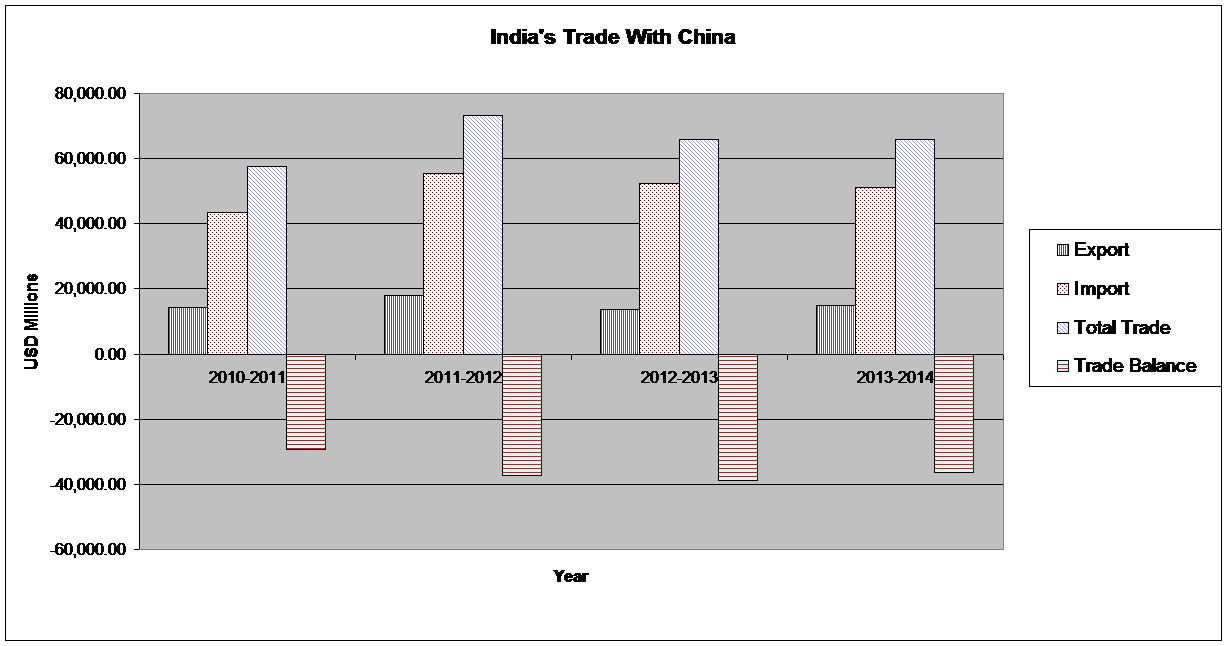

Bilateral economic trade has been growing the last few decades. From a mere US$ 133.5 million in 1988, total trade reached nearly US$ 70 billion in 2014[31]. However, two asymmetries exist within this relationship. Firstly, bilateral trade is less important to Beijing than to New Delhi. Charts 1 and 2 show that while China is India’s top trading partner, their trading volume is only a fraction of the total trade China has with others like the US, South Korea and Japan. Secondly, their bilateral trade has been heavily skewed in China’s favour. Almost 90% of India’s exports to China are low-cost raw materials and iron ore. In contrast, imports from China consist mostly of higher-value finished goods[32]. The result as shown in Chart 3 is a growing trade deficit for India which has become a source of disagreement between the two. India has been pressuring China to import more products in the areas of pharmaceuticals, agricultural produce, energy, etc, and in turn has set high tariffs to protect Indian industries[33].

Chart 1: India’s Foreign Trade in USD Millions (2014)[34]

Chart 2: China’s Foreign Trade in USD Millions (2014)[35]

Chart 3: India’s Trade with China in USD Millions (2010-2014)[36]

Analysis

Characteristics of all three IR theories are reflected in Sino-Indian relations. Realism in general assumes that there is no central power governing the international system. States therefore prioritise self-interest over collective interest and have to accumulate power in order to survive. Such thinking drives states to attain a favourable balance of power and compete for influence. Balancing can consist of internal balancing – building up one’s own power, or external balancing – accumulating power through external relations[37]. Liberalism focuses more on cooperation between states. States that are mutually dependent incur greater political costs in conflicts, and thus choose to pursue peaceful relations. This includes commercial interdependence for trading nations and strategic interdependence for states with nuclear weapons. Participation in international organizations is also believed to promote cooperation, leading to peace. Lastly, constructivism stresses the importance of identities, perceptions, and norms in determining how decisions are made.

For constructivists, the early disputes that marred Sino-Indian relations created a perception of mistrust and hostility. This perception was kept alive and reinforced by the periodical crises arising out of their many unresolved disputes. This situation is further exacerbated by their inescapable geographical proximity and near simultaneous emergence as rising powers. Combining elements of realism and constructivism, it can be argued that competition and friction between the two Asian giants will be inevitable since their common aspiration for great power status would force them to compete for influence, resources, and markets within the same strategic neighbourhood.

This does not mean that war is inevitable. For liberalists, the awesome power of nuclear weapons serves as a major restraint to conflict. Indeed, while crises and even limited conflict has occasionally flared up between past nuclear rivals like US-Soviet Union, India-Pakistan, and China-Soviet Union, caution and restraint was always shown when the danger of escalation loomed[38]. This stability is strengthened when we consider the escalation-resistant nuclear policies of the Sino-Indian nuclear dynamic.

This however, has not prevented their strategic competition which has led to mutual balancing strategies seen in international forums and in the maritime sphere. Both India and China have balanced internally by strengthening their military, and also externally by building relations with each other’s neighbours. Again, their behaviour reveals a convergence of realism and constructivism. Firstly, India has shown greater willingness to work with the US – the preeminent superpower – in order to balance China – whom it perceives as the greater threat. This behaviour demonstrates Stephen Walt’s balance of threat thinking[39], as opposed to balance of power. Secondly, both India and China’s mutually balancing behaviour is driven by the fear of each other’s growing power and their own need to accumulate power for security. This creates an action/reaction dynamic known as a security dilemma which is potentially destabilizing as it creates a negative spiral of increasing tensions and perception of insecurity on both sides.

The security dilemma however, is tempered by policies which seem somewhat inconsistent with realist balancing strategies. First, restraint has been shown in the military-strategic sphere. Both sides have been careful to moderate their actions and avoid getting into strategic agreements that may get them involved in major disputes with each other. Second, is their growing economic interdependence. Such engagement is extremely rare between balancing rivals as it usually leads to dependence of the weaker power upon the stronger[40]. Yet, India has embraced economic trade with China. Thirdly, although they see each other as rivals, their participation in CBMs reveal a genuine interest in strengthening ties.

Their relationship thus reveals an almost paradoxical policy of limited engagement and restrained balancing. What could be the motivation behind such behaviour? Noted political scientist Avery Goldstein provides a clue. He argues that China’s overwhelming imperative since the late 1990s has been to strengthen its economic and military strength while avoiding any external conflict[41]. This “strategy of transition” which is expected to last another thirty to forty years[42], inevitably raises questions about China’s intentions once this transformation is complete.

It is this uncertainty over China’s long-term intentions which has forced India into this two-pronged strategy of engagement and balancing. In the long run, India engages its neighbour both economically and politically to improve ties and hope a friendly China emerges. Simultaneously, India also strengthens its military, preparing itself for the worst case scenario (i.e. internal balancing). It also strengthens ties with China’s neighbours for the purpose of external balancing and to gain access to larger regional trade organizations like the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC).

China’s behaviour mirrors India’s. It pursues engagement since a stable regional environment facilitates the build up of its national strength. China also balances India through internal and external balancing while avoiding overly confrontational behaviour. But while India views bilateral trade through liberalist lenses, China sees it with a realist tinge. Indeed, there have been accusations that China’s trade policies have been designed to weaken her competitors and rivals, which may account for India’s large trade deficit vis-à-vis China[43].

Conclusion

As the analysis has shown, strands of realism, liberalism, and constructivism are inseparably interwoven into Sino-Indian relations. The central motivation for both state’s behaviour is however, fundamentally realist, undergirded by liberalist and constructivist thinking. The ultimate goal for both sides is the accumulation of power. Trade, international cooperation ,and friendly relations are encouraged since it facilitates this power accumulation. For India, such engagement also increases the chances that a friendly China emerges. In parallel, both states seek to expand their influence into each other’s backyard, as a means to accumulate more power and at the same time, undermine their potential future competitor. But this is done in a cautious manner to avoid destabilising relations which would hinder power acquisition.

What does this mean for Sino-Indian relations? With both sides focused on accumulating power and avoiding open conflict, one would expect their relationship to be broadly stable. However, the mutual distrust emanating from unresolved historical disputes coupled with their ongoing competition for overlapping spheres of influence makes it inevitable that intermittent crises will occur. These recurring crises will make complete rapprochement difficult, if not impossible.

Yet, these crises are unlikely to result in escalation for two reasons. Firstly, both India and China have demonstrated great discipline in moderating their military-strategic behaviour. Secondly, the mere presence of nuclear weapons encourages even greater caution and serves to minimise the risk of war. The result is thus, a long-run stability punctuated by occasional disputes and crises. While resolution of their rivalry remains improbable, escalation to war is similarly unlikely. In the long-run, the stability of their relationship will depend on how well both states can manage their competitive strategies and resolve their disputes, which in turn will limit the frequency of crises. There is no doubt however, that nuclear weapons will continue to serve as major limiting factor to war even in the future.

Byron Chong is currently pursuing his Masters in Strategic Studies at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. A passion for history and international politics drew him to this field of study after his first degree in engineering. His current research interests lie in the strategic and security affairs of the Asia Pacific region.

Bibliography

Basrur, R. “India’s Escalation-Resistant Nuclear Posture.” In Escalation Control and the Nuclear Option in South Asia, edited by Michael Krepon, Rodney W. Jones, and Ziad Haider, 56-74. Washington, DC: Henry Stimson Center, 2004.

Basrur, R. “The Politics of Sri Lanka’s Economic Relations with India.” In International Relations Theory and South Asia, Vol. I, edited by E. Sridharan, 242-259. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Basrur, R. “India and China: Nuclear Rivalry in the Making?” RSIS Policy Brief (2013): pp. 1-8. Accessed April 21, 2016. https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/PB131001_India_and_China_Nuclear_Rivalry.pdf

Basrur, R. “Nuclear Deterrence: The Wohlstetter-Blackett Debate Re-visited.” RSIS Working Paper, No. 271 (2014): 1-29. Accessed April 2, 2016. https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/rsis-pubs/WP271.pdf

Brewster, D. “Beyond the ‘String of Pearls’: Is there really a Sino-Indian security dilemma in the Indian Ocean?” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 10, No. 2 (2014): 133-149.

Egreteau, R. “The China-India Rivalry Reconceptualized.” Asian Journal of Political Science 20, No. 1 (2012): 1-22.

Frankel, F. R. “The Breakout of China-India Strategic Rivalry in Asia and the Indian Ocean.” Journal of International Affairs 64, No. 2 (2011): 1-17.

Garver, J. W. “The Security Dilemma in Sino-Indian Relations.” India Review 1, No. 4 (2002): 1-38.

Goldstein, A. “An Emerging China’s Emerging Grand Strategy.” In International Relations Theory and the Asia-Pacific, edited by John Ikenberry and Michael Mastanduno, 57–106. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003.

Goldstein, A. Rising to the Challenge: China’s Grand Strategy and International Security. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 2005.

India Department of Commerce, “Export Import Data Bank.” Ministry of Commerce and Industry, 2015. Accessed January 21, 2016, http://commerce.nic.in/eidb/iecntq.asp

Jacob, J. T. “India’s China Policy: Time to Overcome Political Drift,” RSIS (2012): 1-8. Accessed January 21, 2016, from RSIS: https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/PB120601_India_China_Policy.pdf

Kumar, V. “India well positioned to become a net provider of security: Manmohan Singh.” The Hindu, May 23, 2013. Accessed January 21, 2016. http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/india-well-positioned-to-become-a-net-provider-of-security-manmohan-singh/article4742337.ece

Malik, M. China and India: Great Power Rivals. Boulder, CO: First Forum Press, 2011.

Malone, D. M., and Rohan Mukherjee. “India and China: Conflict and Cooperation.” Survival 52, No. 1 (2010): pp. 137-158.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2015. “China Statistical Yearbook – Value of Imports and Exports by Country (Region) of Origin/Destination.” China Statistics Press (2015). Accessed January 21, 2016. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2015/indexeh.htm

Panda, A. “India is capable of developing a 10,000-Kilometer range ICBM.” The Diplomat, April 6, 2015. Accessed January 21, 2016. http://thediplomat.com/2015/04/india-is-developing-a-10000-kilometer-range-icbm/

Pandit, R. “China-specific Agni III to be tested today.” The Times of India, May 7, 2008. Accessed January 21, 2016, from: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/China-specific-Agni-III-to-be-tested-today/articleshow/3016689.cms

Scott, D. “Sino-Indian Security Predicaments for the Twenty-First Century.” Asian Security 4, No. 3 (2008): 244-270.

Sitaraman, S. “South Asia: Conflict, Hegemony, and Power Balancing.” In Beyond Great Powers and Hegemons: Why Secondary States, Support, Follow, or Challenge, edited by Kristen P. Williams, Steven E. Lobell, and Neal G. Jesse 177-192. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012.

US Department of Defence. Annual Report to Congress: Military and security developments involving the People’s Republic of China. Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defence, 2012.

Walt, S. W. “Alliance Formation and the Balance of World Power.” International Security 9, No. 4 (1985): 3-43.

[1] David. M. Malone and Rohan Mukherjee, “India and China: Conflict and Cooperation,” Survival 52, no. 1 (2010): 137-138.

[2] Rajesh Basrur, “India and China: Nuclear Rivalry in the Making?” RSIS Policy Brief (2013): 3.

[3] John W. Garver, “The Security Dilemma in Sino-Indian Relations,” India Review 1, no. 4 (2002): 6.

[4] ibid.

[5] Malone and Mukherjee, “India and China,” 142.

[6] Mohan Malik, China and India: Great Power Rivals (Boulder, CO: First Forum Press, 2011), 42.

[7] Srinivasan Sitaraman, “South Asia: Conflict, Hegemony, and Power Balancing,” in Beyond Great Powers and Hegemons: Why Secondary States Support, Follow, or Challenge, eds. Kristen P. Williams et al. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012), 184.

[8] Malik, China and India, 58.

[9] Renaud Egreteau, “The China-India Rivalry Reconceptualized,” Asian Journal of Political Science 20, no. 1 (2012): 9-10.

[10] ibid., 9.

[11] Malone and Mukherjee, “India and China,” 144.

[12] Francine R. Frankel, “The Breakout of China-India Strategic Rivalry in Asia and the Indian Ocean,” Journal of International Affairs 64, no. 2, (2011): 3.

[13] Jabin T. Jacob, “India’s China Policy: Time to Overcome Political Drift,” RSIS (2012): 5, accessed January 21, 2016, RSIS: https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/PB120601_India_China_Policy.pdf

[14] Malik, China and India, 44.

[15] Malik, China and India, 55.

[16] ibid., 46-77.

[17] US Department of Defence. Annual Report to Congress: Military and security developments involving the People’s Republic of China. (Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defence, 2012), 12.

[18] John W. Garver, “The Security Dilemma in Sino-Indian Relations,” India Review 1, no. 4 (2002): 13-14.

[19] David Brewster, “Beyond the ‘String of Pearls’: Is there really a Sino-Indian security dilemma in the Indian Ocean?” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 10, no. 2 (2014): 137.

[20] Garver, “Security Dilemma,” 5.

[21] Vinay Kumar, “India well positioned to become a net provider of security: Manmohan Singh,” The Hindu, May 23, 2013, accessed January 21, 2016, http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/india-well-positioned-to-become-a-net-provider-of-security-manmohan-singh/article4742337.ece

[22] Garver, “Security Dilemma,” 6.

[23] Brewster, “String of Pearls,” 135.

[24] Ankit Panda, “India is capable of developing a 10,000-Kilometer range ICBM,” The Diplomat, April 6, 2015, accessed January 21, 2016, http://thediplomat.com/2015/04/india-is-developing-a-10000-kilometer-range-icbm/

[25] David Scott, “Sino-Indian Security Predicaments for the Twenty-First Century,” Asian Security 4, no. 3 (2008): 259.

[26] Brewster, “String of Pearls,” 146.

[27] Scott, “Security Predicaments,” 254.

[28] Rajat Pandit, “China-specific Agni III to be tested today,” The Times of India, May 7, 2008, accessed January 21, 2016, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/China-specific-Agni-III-to-be-tested-today/articleshow/3016689.cms

[29] Rajesh Basrur, “India’s Escalation-Resistant Nuclear Posture,” in Escalation Control and the Nuclear Option in South Asia, ed. Michael Krepon, et al. (Washington, DC: Henry Stimson Center, 2004), 57.

[30] Rajesh Basrur, “India and China: Nuclear Rivalry in the Making?” RSIS Policy Brief (2013): 7, accessed April 21, 2016, https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/PB131001_India_and_China_Nuclear_Rivalry.pdf

[31] India Department of Commerce, “Export Import Data Bank,” Ministry of Commerce and Industry, 2015, accessed January 21, 2016, http://commerce.nic.in/eidb/iecntq.asp

[32] National Bureau of Statistics of China, “China Statistical Yearbook – Value of Imports and Exports by Country (Region) of Origin/Destination,” China Statistics Press, 2015 accessed January 21, 2016, http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2015/indexeh.htm

[33] India Department of Commerce, “Export Import Data Bank.”

[34] ibid.

[35] Malik, China and India, 46.

[36] ibid.

[37] Scott, “Security Predicaments,” 247.

[38] Rajesh Basrur, “Nuclear Deterrence: The Wohlstetter-Blackett Debate Re-visited,” RSIS Working Paper, no. 271 (2014): 15, accessed April 2, 2016, https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/rsis-pubs/WP271.pdf

[39] Stephen M. Walt, “Alliance Formation and the Balance of World Power,” International Security 9, no. 4 (1985).

[40] Rajesh Basrur, “The Politics of Sri Lanka’s Economic Relations with India,” in International Relations Theory and South Asia Vol. I, ed. E. Sridharan, (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2011), 244.

[41] Avery Goldstein, “An Emerging China’s Emerging Grand Strategy,” in International Relations Theory and the Asia-Pacific, eds. John Ikenberry and Michael Mastanduno. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 60.

[42] Avery Goldstein, Rising to the Challenge: China’s Grand Strategy and International Security (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005), 38.

[43] Malik, China and India, 57.

Featured Image: Chinese and Indian border troops stand together at border crossing.