By Tyler Cross

In 1827, Sir William Parry of the British Royal Navy made the first serious attempt to reach the North Pole. Captain of the Hecla, he and his crew reached 82°45’ N, a record for humanity for the northernmost latitude reached; it remained unbroken for 49 years. Exploration of the Arctic, closely related with the search for the ever-elusive Northwest Passage, became the fascination of explorer and layman alike during the 19th century.1 But frozen in time and locked in ice, the Arctic was impassable, mysterious, and unobserved until the early 20th century.

The High North that Parry and other explorers tried to reach was quite different from the Arctic today. Polar ice caps are receding at a steady rate. The titanic expanses of ice sheets are shrinking, exposing greater topography at the top of the world.

This will present unique security challenges for the 21st century. The Arctic may become a highway and natural resource center in the future. Tensions between NATO states and Russia are already palpable, and are poised to increase. Security challenges are driven in part by trade and resource potential in the Arctic Ocean. Oil, natural gas, immense fisheries, and potential maritime highways via the Northwest Passage and Northern Sea Route are likely sticking points.2 The Russian Federation has, through its own renewed tension building and aggressions, positioned itself as the principal potential adversary in the High North. Moscow sees great developmental opportunities in the Arctic. The Russians are far greater equipped – both psychologically and materially, for staying power in the frozen wilderness. It is an integral part of Moscow’s future plans.

https://gfycat.com/welltododarlingachillestang

Time lapse of the relative age of Arctic sea ice from week to week since 1990. The oldest ice (9 or more years old) is white. Seasonal ice is darkest blue. Old ice drifts out of the Arctic through the Fram Strait (east of Greenland), but in recent years, it has also been melting as it drifts into the southernmost waters of the Beaufort Sea (north of western Canada and Alaska). Video produced by the Climate.gov team, based on data provided by Mark Tschudi, University of Colorado-Boulder. (NOAA via Climate Central)

In contrast, high latitudes receive far less attention and interest in the United States. The NATO alliance, driven particularly by the Arctic nations, will be pivotal in a joint security role there. Canada, Norway, Iceland, and Denmark, all NATO allies with shores on the Arctic Ocean, should be incorporated and extensively consulted. Finland, another NATO partner in the Arctic but with no direct access to the Arctic Ocean, and Sweden, a friendly security partner with ties to the alliance, will also play their respective roles in mutual cooperation.

Cooperation with Moscow, while ideal, is unlikely. Contingencies must be prepared. Russian capability, at least for trade supported by icebreaking, dwarfs that of the United States. NATO allies and Northern European friends also largely outpace U.S. icebreaking capability. The development of icebreakers will be a focal point of the road ahead. They open sea lanes in the warmer months, facilitating trade and movement of the naval surface fleet. Of secondary concern is China, which has an active duty icebreaker capability and is currently using its icebreakers to explore potential oil drilling sites that could impede U.S. economic zones in the Arctic.3

Security in the Arctic Ocean will grow in importance as the polar ice caps shrink. Therefore the United States, in conjunction with NATO allies, must develop appropriate security doctrine and measures that confront the dangers of the High North and Russian militarization in order to provide freedom of navigation in this often neglected theater.

Less Ice, More Activity

The Arctic is a treasure trove of natural resources. It is also the least understood ocean. Thus, the story of security there has an air of mystique and discovery. Largely untapped resources exist, and much of them are yet to be discovered. Humanity has mapped the surface of the Moon and Mars to a greater extent than the ocean floor of the Arctic. But what is generally understood is that there are vast resources to be harnessed. It is estimated that 30 percent of the world’s untapped hydrocarbons can be found in the Arctic, including a full 25 percent of proven hydrocarbon reserves. Much nickel, platinum, palladium, lead, diamonds, and other rare Earth metals are there as well.4 In the 21st century, there will be a maritime “gold rush” to the upper latitudes once conditions permit.

Russia, an energy giant, has made great economic strides in the 21st century through the export of oil. It has found dependable markets in Europe and Northeast Asia. Even NATO member states with unfriendly relations with Moscow find themselves largely dependent on Russian oil imports. Likewise, in Northeast Asia, new markets have been found in historically unfriendly states, like South Korea.5 Vladimir Putin is now looking to the Arctic to help solidify his nation’s status as Eurasia’s energy giant. And as the economic, industrial, and military power of Russia and China increase, they will both look to the Arctic as a natural resource center from which they can pull materials.

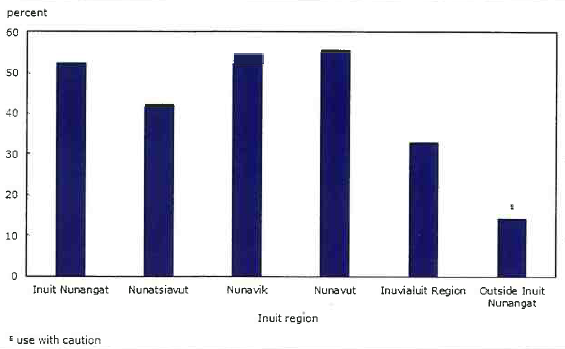

The Arctic is a considerable source of fisheries. In the United States, 50 percent of fish stocks originate within the 200-mile exclusive economic zone off the coast of Alaska. Many of the other Arctic states have similar extensive fishing operations off of their immediate coasts. There is great competition and overfishing beyond the EEZs.6 In future food crises, industrial fishing will be forced to venture farther to find plentiful stocks, and many will certainly look to the Arctic. Increased economic competition and interest will likely drive a greater need for security. This will in turn lead to a degree of militarization previously unseen in the Arctic.

If for no other reason, U.S. interest is prompted by increased trade. One of the core stated goals of the United States Navy is upholding the principle of the freedom of navigation. Currently, the U.S. Navy is the world’s enforcer of free trade on the open ocean and carries exponentially more of the burden than any other state’s navy. If the Arctic finds itself inundated with commercial fishing interests between competing states, especially ones desperately looking to compensate for declining fish stocks elsewhere, the Navy will likely be pulled toward the Arctic.

It would behoove decision-makers to recognize the future of the Arctic’s importance, and they must be willing to provide security to American and allied civilian operations there if in danger. But the U.S. Navy is currently stretched thin, focusing on protecting freedom of navigation and security, especially in the Pacific, while supporting other interests worldwide. The opening of the Arctic Ocean and its subsequent intensive economic development will almost certainly require naval expansion. If prepared with doctrine now, later challenges will be mollified.

One of the biggest driving factors in sending more naval forces to the Arctic will be newfound trade routes that come from melting ice caps. The Northwest Passage, long a source of fascination for countless explorers, Parry included, is rapidly becoming a viable trade route. But as the ice thins and becomes a potential sea lane, the future of the Northwest Passage remains unclear. The sea route stretching from Baffin Bay to the Beaufort Sea runs through Canadian waters. The Canadian government would like to see this recognized as their own territorial waters, while other maritime powers, particularly the United States, would like to see the region be recognized as an international highway.7 Far more contentious and potentially volatile is the Northern Sea Route. With the potential to cut transit distance between Europe and Asia by 40 percent, the Northern Sea Route could become an international highway in a more open Arctic. But disputes over its use between the United States and Russia date back to the 1960s. Then and today, Moscow treats the passage as territorial waters over which they have control. The United States, in its freedom of navigation mission, declares that the lanes must be open. Russia will continue to exercise claimed rights, citing the Law of the Sea, that the straits are their historic territorial waters. Under such provisions, they can claim modern legislation.8 Russia’s economy is largely dependent on energy exports, and it may look to diversify and tax shipments moving through the Northern Sea Route. Putin may try to use the opening lanes as a source of steady income and as a pressure point on other powers. He will also likely use militarization in the High North to enforce and buttress territorial claims.

Another developing commercial route is in the Bering Strait between Alaska and Russia’s Easternmost reaches. The United States Coast Guard reported a 120 percent increase in Bering Strait traffic from 2008 to 2012.9 The Bering Sea is unforgiving and with all of this increased traffic there are bound to be more sailors in danger due to the intense weather and equipment failure that often occurs in these locations. Barrow, at the northern tip of Alaska, is generally accessible only by air, but traffic will increase in the warm summers to come. Remote Arctic littorals near Alaska experience year-round tempestuous weather, little cellular coverage, and limited search and rescue availability. The nearest USCG air station to Barrow can be found in Kodiak, 1000 miles away. In the words of Admiral James Stavridis, “All of this means that if a mariner is in trouble in the Arctic, he or is she is in serious trouble.”10

Traffic has grown at an unprecedented rate, and now is the time to develop more search and rescue proficiency and capability. Much of this will fall on the Coast Guard, but it is unfortunately underfunded and understaffed despite the fact it will bear the greatest burden in a developing Arctic. Creating new or better search and rescue capabilities in Alaska is substantially cheaper than most military projects. The funding would be comparatively little, but the repercussions great. This will be a continuous theme in the Arctic, and some modern investments in Coast Guard capabilities will not come easily, but they will be well worth the effort and remain economical within the Department of Defense and Department of Homeland Security budgets.

As of 2011, Russia and the U.S. created the new Arctic Search and Rescue Agreement. The safety realm seems to be one of the few topics their armed forces can agree on. Russia has been developing ten search and rescue bases along its Northern Sea Route, yet this development coincides ominously with more militarization in the same area.11 But cooperation between Russian and American Coast Guards will be beneficial in saving lives. More cooperative capability for search and rescue will hopefully not coincide with greater tensions vis-à-vis military development. The Arctic Search and Rescue Agreement is an encouraging step in separating great power rivalry from life-saving operations that benefit all.

Strategy and Security – The Russian Federation

The Arctic is central to the Russian worldview. Part of the Russian identity is that of the rugged individual capable of self-sustaining life in harsh, cold climates. The High North, with its frigid tundra and plentiful natural resources, is integral to the very fiber of Russian culture. In addition, Russia has the largest population living above the Arctic Circle, totaling approximately four million.12 By contrast, the Arctic is far removed from the culture of American society. It would behoove strategists to appreciate these cultural difference when approaching security concerns and understanding motivations. The world’s northernmost reaches will never hold the same societal importance to Americans as it does to Russians.

Perhaps more so than the average Russian, leaders in the Kremlin look to the High North with envy. Putin’s plans for Arctic development can be thought of like former President Barack Obama’s “Pivot to Asia” strategy. Much of Moscow views the Arctic similar to how the 44th president saw the Western Pacific, a place of developmental opportunities and of increasing importance to national strategy. According to The National Security Strategy of the Russian Federation Through 2020, the Arctic is set to become Russia’s “top strategic resource base by 2020.” Furthermore, the Kremlin did not rule out military conflict in the region if this strategic goal was threatened.13 A large portion of the National Security Strategy document was devoted to the Arctic, embodied in the “Principles of State Policy of the Russian Federation in the Arctic Through 2020 and Beyond.” Included was a plan to strengthen military presence.

Putin’s pivot to the North is not just economic, but also militaristic. The Arctic is home to the North Sea Fleet, which includes much of the Russian ballistic missile submarine fleet. During the Cold War, American and Soviet nuclear submarines played endless “cat and mouse” games in the frigid, quiet waters beneath the Arctic ice.14 Despite the thaw of the Cold War, tensions have again risen to significant levels, and Russia has a large military that it is willing to utilize. This was illustrated in 2008 with the short war against Georgia, in 2014 with the annexation of Crimea, and from 2015 to the present day in Syria. In recent years, the number of troops in Arctic bases has increased, and the bases themselves have grown with haste. As the polar ice caps recede, there will be a strong inclination to develop naval capabilities to defend newly exposed northern shores.15

Russian military and economic development in the Arctic will be linked in the coming decades. Military centers are not far from important sources of income. Approximately 22 percent of the Russian Federation’s GDP is produced above the Arctic Circle. Russian sources claim that as much as 90 percent of their hydrocarbon reserves can be found in the Arctic, concentrated mostly in the Barents Sea and Kara Sea.16 The Barents Sea, situated north of the European theater, is naturally critical to the Russians. Murmansk and Arkhangelsk are two of Russia’s most important historical cold water ports. Both are situated at the southern reaches of the Barents Sea, or at the northern tip of Europe. Both ports are home to the Northern Fleet, and Murmansk is the administrative center of the fleet. And important offshore natural resources can be found not far away from long-established military bases in Russia’s most militarized regions.

Russia is an oil producing giant, and where Gazprom is the largest Russian energy firm. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it is tightly controlled by the Kremlin, and when Gazprom makes money, the state makes money.17 Putin and his associates will look to jealously guard their economic development in the Arctic, and the Kremlin has explicitly stated it needs a “necessary combat potential” in the Arctic. Regular border guard patrols out of Murmansk and Arkhangelsk were re-activated in 2009, reminiscent of the Soviet Union days. Around this time, it was announced that a new Arctic Spetsnaz unit would come into existence.18 In March of 2015, Russia practiced the largest Arctic military deployment since the Cold War when it mobilized 45,000 soldiers, 3,360 vehicles, 110 aircraft, 41 naval vessels, and 15 submarines in a force readiness exercise.19 Likewise, submarine capability beneath the ice has been revitalized and Russia’s submarine fleet has grown. While some militarization is probably just for basic security purposes, much of it coincides with the protection of expanding oil wealth generated near and within the Arctic Circle.

The Russian Federation’s true power at sea, like the Soviet Union before it, lies in its submarine fleet.20 And nowhere is a submarine force more independently powerful than under the Arctic ice. Russia’s submarine force is plentiful, but aging. Moscow has accordingly begun developing Russian submarine capabilities that will make the fleet formidable well into the 21st century. In the Russian Navy’s 2011-2020 modernization plan, it has completed the construction of three Borei class ballistic missile submarines and two Yasen-class guided-missile submarines, along with the refurbishment of Soviet-era nuclear powered subs. By 2021, Russia plans on completing five new Borei-class ships and four to five new Yasen-class ships by 2023.21 With assets to guard in the Arctic, Russia’s increasingly formidable submarine force will likely look to increase patrols in these icy waters. Maneuvers and rhetoric, however, have not gone unnoticed and have begun to attract the attention of NATO.22 And although the Russian military is outmatched by NATO in certain dimensions, a Russian military advantage in the Arctic is conceivable.

Conclusion

The Arctic, with great potential for development and cooperation, is also a theater of growing tension. For this reason, the U.S. must give much greater priority to the Arctic. Development of strategic planning is the first move – something that has only recently begun to appear. It is encouraging that defense planners and policy makers alike have recognized this, but there are great improvements still to be made. The second move is the creation of serious military capability in the High North, spearheaded by the United States Coast Guard, which at present lacks the ability to sustain operations in the frozen wilderness of the planet’s northernmost reaches.

The story of Arctic security invariably involves the Russian Federation. Moscow is motivated by prestige, nationalism, and economic potential. Vladimir Putin has made public his intentions to defend and build Russian pride.23 This will be transposed to the High North. In recent history Moscow has pursued an active military policy, and this trend is poised to continue. Understanding Russian motivations and goals in the Arctic will be imperative in creating sound Arctic defense policy.

Tyler Cross recently completed a master’s degree in International Security at George Mason University. He will continue his career in international security cooperation.

References

[1] Hampton Sides, In the Kingdom of Ice The Grand and Terrible Polar Voyage of the USS Jeannette, (New York: Anchor Books, 2014), p. 21.

[2] James Stavridis, Sea Power The History and Geopolitics of the World’s Oceans, (New York: Random House, 2017), pp. 332-333.

[3] Megan Eckstein, “Zukunft: Changing Arctic Could Lead to Armed U.S. Icebreakers in Fleet, U.S. Naval Institute News, May 18, 2017, https://news.usni.org/2017/05/18/zukunft-changing-arctic-environment-could-lead-to-more-armed-icebreakers-in-future-fleet.

[4] Stavridis, pp. 329, 332.

[5] Gilbert Rozman, Strategic Thinking about the Korean Nuclear Crisis Four Parties Caught between North Korea and the United States, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 91-93.

[6] Stavridis, p. 332.

[7] Andrey A. Todorov, “The Russia-USA Legal Dispute Over the Straits of the Northern Sea Route and Similar Case of the Northwest Passage,” Arktika I Sever, no. 29 (2017): pp. 71-73.

[8] Ibid, pp. 62-65.

[9] Stavridis, pp. 333-334.

[10] Ibid., pp.336-337.

[11] David Slayton and Lawson W. Brigham, “Can the US and Russia Preserve Peace in the Arctic?,” Investor’s Business Daily, May 13, 2015, p. A13.

[12] Stavridis, pp. 341-342.

[13] Kari Roberts, “Jets, Flags, and a new Cold War? Demystifying Russia’s Arctic Intentions,” International Journal, 65, no. 4 (2010): p. 966.

[14] Stavridis, pp. 342-343, 354.

[15] Ibid., p. 342.

[16] Katarzyna Zysk, “Russia’s Arctic Strategy: AMBITIONS AND CONSTRAINTS,” Joint Force Quarterly, 57 (2010): p. 105.

[17] Roberts, pp. 963-964.

[18] Zysk, p. 107.

[19] Kristina Spohr, “The Scramble for the Arctic,” New Statesman, 147 (March 9-March 15, 2018): pp. 22-27.

[20] Michael Kofman, “Russia’s Fifth Generation Sub Looms,” U.S. Naval Institute, Proceedings Magazine 143, no. 10 (October 2017).

[21] Ibid. The Yasen class is commonly referred to as “Severodvinsk” in NATO circles.

[22] Zysk, p. 109.

[23] Paul Dibb, “The Geopolitical Implications of Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine,” Strategic and Defense Studies Center, June 2014, p. 5.

Featured Image: Navy Seals training for winter warfare at Mammoth Mountain ski area in California on December 9, 2014. (U.S. Navy Photo by Visual Information Specialist Chris Desmond)