The Persian Gulf sits at the nexus of multiple regional security complexes overlaid one upon another, creating a delicately balanced yet dangerously volatile mosaic of cultural politics and armed forces. As a result, the calculated political positioning of states within the region have ramifications that produce a ripple effect across the entire globe: affecting energy markets, political stability, and military cooperation and procurement programs which define how several non-regional states engage.

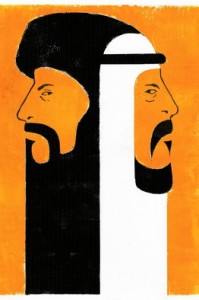

At the core of this Gulf complex is a security rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran; a centuries old antagonism between Sunni and Shia’ Muslims manifest in global politics which now dictates defense alignment policies and military readiness. A second, and rising, security complex to examine is the establishment of the United States as a permanent military, economic, and diplomatic partner in the region – absent only in sovereign territory of its own. With the presence of the US Fifth Fleet in Bahrain, American interests in the region are clearly communicated, as are the passive-aggressive cavitation of our naval vessels plying the Straits of Hormuz at the dismay of Iran’s Supreme leader. Third, Gulf security politics exist within the broader global context of a contentious Muslim and Jewish relationship, most clearly exhibited by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. To this point, it is argued that much of the anti-Israeli rhetoric coming from Iran, for example, can be explained by recognizing Iran’s need to appear as the sole, legitimate voice of Muslims in the Gulf as opposed to Saudi Arabia. Last, this piece will address the strategic importance of an American presence in the Persian Gulf to fulfill President Obama’s pivot towards Asia. Tangled in an economic complex with the Middle East, major Pacific actors have made attempts to use their geographic back door in South Asia to secure natural resources, thus sustaining the growing trend of urbanization in Asia. Because of this, the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review calls for a continued American presence in the Gulf as a key stratagem to check expanding Chinese power.

At the core of this Gulf complex is a security rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran; a centuries old antagonism between Sunni and Shia’ Muslims manifest in global politics which now dictates defense alignment policies and military readiness. A second, and rising, security complex to examine is the establishment of the United States as a permanent military, economic, and diplomatic partner in the region – absent only in sovereign territory of its own. With the presence of the US Fifth Fleet in Bahrain, American interests in the region are clearly communicated, as are the passive-aggressive cavitation of our naval vessels plying the Straits of Hormuz at the dismay of Iran’s Supreme leader. Third, Gulf security politics exist within the broader global context of a contentious Muslim and Jewish relationship, most clearly exhibited by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. To this point, it is argued that much of the anti-Israeli rhetoric coming from Iran, for example, can be explained by recognizing Iran’s need to appear as the sole, legitimate voice of Muslims in the Gulf as opposed to Saudi Arabia. Last, this piece will address the strategic importance of an American presence in the Persian Gulf to fulfill President Obama’s pivot towards Asia. Tangled in an economic complex with the Middle East, major Pacific actors have made attempts to use their geographic back door in South Asia to secure natural resources, thus sustaining the growing trend of urbanization in Asia. Because of this, the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review calls for a continued American presence in the Gulf as a key stratagem to check expanding Chinese power.

Conceptual Framework:

Proposed by Barry Buzan in his 2003 publication Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security, regional security complex theory tells us that a relationship between two countries is often dictated by contextual factors rather than a direct binary balance of power dynamic.  This checkers to chess dynamic is found in Southeast Asia where ASEAN states coordinate diplomatic, economic, and security interests according to a broader context of Chinese encroachment into the South China Sea. Furthermore, Buzan suggests that a security complex applies not only to states that share a region, but also implicates states that have shared economic and security goals in absence of shared borders. An example of this would be the seemingly puzzlingly and provocative rhetoric of Israeli statesmen who are factually out numbered and surrounded by opposition in the Middle East. However, when considering the added influence of American military power that backs Israel, it becomes clear that one cannot simply understand Israeli foreign policy in the region without first considering its dependent relationship upon the raw capabilities of the United States in projecting power onto countries such as Syria, Iraq, and Iran.

This checkers to chess dynamic is found in Southeast Asia where ASEAN states coordinate diplomatic, economic, and security interests according to a broader context of Chinese encroachment into the South China Sea. Furthermore, Buzan suggests that a security complex applies not only to states that share a region, but also implicates states that have shared economic and security goals in absence of shared borders. An example of this would be the seemingly puzzlingly and provocative rhetoric of Israeli statesmen who are factually out numbered and surrounded by opposition in the Middle East. However, when considering the added influence of American military power that backs Israel, it becomes clear that one cannot simply understand Israeli foreign policy in the region without first considering its dependent relationship upon the raw capabilities of the United States in projecting power onto countries such as Syria, Iraq, and Iran.

The application of this theory in the Persian Gulf helps to explain the relationship between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Evident in the coordinated relations of Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, which include Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates, a security complex emerges that explains the alignment of foreign and defense policies in opposition to Iran.  Placating to the politics of identity and culture, the complex provokes an arms and ideological race between Saudi Arabia and Iran that is executed by proxy across the region. The concern regarding this ideological race is not that it is fought over religious differences, but rather that their cold war is fought within the context of suppressing unalienable freedoms according to ethnic fault lines. Quite possibly warming the conflict to a more traditional shooting engagement, ideological grievances often result in genocidal war crimes. As a pretext to the grim reality of a coming ideological conflict between the two nations, Iran’s limited offensive role against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) seeks to avoid, in the interpretive eyes of Saudi Arabia, this very scenario—despite Saudi’s open disapproval of ISIL’s advancements. Ultimately, neither country wants to engage in combat with the other, but their regional posturing is motivated by both an effort to omnibalance and offset an internal threat to stability while professing a legitimate claim to the Muslim caliphate to external entities. Most interestingly, F. Gregory Gause III, author of The International Relations of the Persian Gulf, poses an important question in this discussion: Can we consider the United States as part of the Persian Gulf’s regional security complex even though the country is not physically part of the region?

Placating to the politics of identity and culture, the complex provokes an arms and ideological race between Saudi Arabia and Iran that is executed by proxy across the region. The concern regarding this ideological race is not that it is fought over religious differences, but rather that their cold war is fought within the context of suppressing unalienable freedoms according to ethnic fault lines. Quite possibly warming the conflict to a more traditional shooting engagement, ideological grievances often result in genocidal war crimes. As a pretext to the grim reality of a coming ideological conflict between the two nations, Iran’s limited offensive role against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) seeks to avoid, in the interpretive eyes of Saudi Arabia, this very scenario—despite Saudi’s open disapproval of ISIL’s advancements. Ultimately, neither country wants to engage in combat with the other, but their regional posturing is motivated by both an effort to omnibalance and offset an internal threat to stability while professing a legitimate claim to the Muslim caliphate to external entities. Most interestingly, F. Gregory Gause III, author of The International Relations of the Persian Gulf, poses an important question in this discussion: Can we consider the United States as part of the Persian Gulf’s regional security complex even though the country is not physically part of the region?

In order to answer this question, and others regarding the Persian Gulf security complex, we must first explore how the Gulf security environment has changed since the end of the Iran-Iraq War. Second, we will explore how changes in U.S. foreign policy have affected the region, highlighting significant issues that exist today whose solutions are a requisite to ushering peace and security into the region.

A Changing Gulf Security Environment:

At the close of the Iran-Iraq War in 1989, the Gulf security environment changed drastically in three ways. First, the international community developed an altered understanding of Saddam Hussein, and his desire for regional control.  After eight years of bloody stalemate, it was clear that Hussein was committed to making offensive gains along Iraq’s borders, particularly if it included a deep-water port or improved access to the Euphrates River south of Basra. Second, there was a paradigm shift in the Westphalian system marked by the fall of the Soviet Union. The unilateral dominance of the United States across the globe introduced the world’s sole super power—capable of projecting military might to the farthest reaches of the globe. Third, following the Iraq War from 2003-2011, the balance of power shifted from a tripolar political dynamic between Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, to a bipolar system where Saudi Arabia and Iran were left to their own devices.

After eight years of bloody stalemate, it was clear that Hussein was committed to making offensive gains along Iraq’s borders, particularly if it included a deep-water port or improved access to the Euphrates River south of Basra. Second, there was a paradigm shift in the Westphalian system marked by the fall of the Soviet Union. The unilateral dominance of the United States across the globe introduced the world’s sole super power—capable of projecting military might to the farthest reaches of the globe. Third, following the Iraq War from 2003-2011, the balance of power shifted from a tripolar political dynamic between Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, to a bipolar system where Saudi Arabia and Iran were left to their own devices.

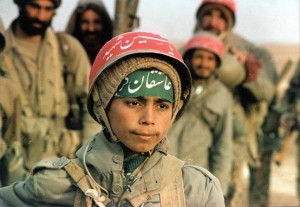

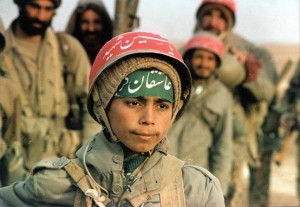

Though the Iran-Iraq War ended with over 400,000 killed, along with an additional 700,000 injured, neither Iran nor Iraq was able to make substantive land gains on either side of the mine-infested fields along the Euphrates. What did change, however, were the attitudes of both Iraqi and Iranian citizens, which created a nationalist fervor in both countries thus, informing the nature of the regional security complex that was to follow. For Iran, the country had successfully defended itself at great personal sacrifice, which united the newly established government with its people. Iraq, on the other hand, experienced the feelings of embarrassment and loss despite the conflict best characterized as a draw. Paranoid of being overthrown by is own people and feeling the pressure to act, Saddam engaged the ebbing tide of Iraqi nationalism and internal reconciliation process to put his military back to work by invading Kuwait. In tandem with the incessant need to conquer something in the region proving his military prowess and invigorating the floundering sense of Iraqi nationalism, Saddam Hussein publically declared several justifications for invading Kuwait. The first of these justifications was that Kuwait was allegedly stealing Iraq’s petroleum reserves, in conjunction with manipulating the energy market with overproduction in order to damage the Iraqi economy. As a result, and through the use of violence, Iraq attacked Kuwait increasing their littoral access from 30-miles of marshland originally proctored by the British, to 300-miles of coastline, which included Kuwait’s Shuwaikh Port—providing deep-water access to Iraqi sea vessels. In addition, perhaps, Saddam may have wanted to highlight to the world the West’s hypocritical tolerance for Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territory, but intolerance towards Iraq’s semi-legitimate legal claim to Kuwaiti soil. Saddam’s understanding of this legal right is grounded in an Ottoman land-use agreement demarcating parts of present day Kuwaiti under the control of Ottoman governors residing in the sub-regional capital of Basrah, Iraq.

Another significant shift occurring after the Iran-Iraq War was the world’s perception of Saddam, and a new international understanding that Iraq was an aggressor towards other Gulf States. This belief was perpetuated across the globe and reinforced by Saddam’s prompt invasion of a sovereign Kuwait. It was believed that Iraq’s move to invade Kuwait in the immediate shadow of their eight-year stalemate with Iran indicated that “Saddam’s quest to dominate the Gulf” would continue. As a result the United Nations passed a Security Council Resolution condemning Iraq’s invasion and in January of 1991, the U.S. Congress voted to authorize the use of force to remove Iraqi forces from Kuwait. The results of this vote represented two momentous transformations in the region, the first being the introduction of what would become a permanent U.S. military force—the first such permanent foreign presence in the Gulf since the exit of the British after World War II, and second the United States massed forces in Saudi Arabia establishing an American interventionist precedent in the heart of Islam’s holiest location. The massing of forces in Saudi Arabia not only loaned the name of American military power and might to the Saudis, but it solidified a formal military alliance, which turned the tables against Iran. After the United States’ impressive 100-hour ground assault driving Iraqi forces out of Kuwait, the door was open to the United States to establish a foothold in the region, giving the Americans a strategic upper hand in military and economic matters. It should be noted that though Iran was having its long-time Iraqi enemy destroyed by American forces, leadership in the Islamic Republic was concerned with the growing U.S. influence in the region.  At the end of the ground campaign, President George H. W. Bush stopped short of marching to Baghdad and signed a bilateral agreement with Iraq, sparing the remaining Iraqi military units and leaving Saddam in power—Iran, among others, was disconcerted with this outcome, but had few bargaining chips to use with the U.S. embassy hostage fiasco fresh in the minds of American policymakers.

At the end of the ground campaign, President George H. W. Bush stopped short of marching to Baghdad and signed a bilateral agreement with Iraq, sparing the remaining Iraqi military units and leaving Saddam in power—Iran, among others, was disconcerted with this outcome, but had few bargaining chips to use with the U.S. embassy hostage fiasco fresh in the minds of American policymakers.

Coinciding with the end of the Iran-Iraq War, the collapse of the Soviet Union emphasized American military dominance and the new world order underwritten by its power. These international phenomena empowered America, and encouraged U.S. diplomats and military leaders to explore their newfound role as the world’s sole superpower. Because of their new position of leadership in the world followed by the resounding victory in Kuwait, the United States gained both soft and hard power for dealing with security issues in the Middle East. The growing influence of the United States in the region was epitomized by the 1995 reactivation of the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet, subsequently assigned a homeport in Khawr al Qulay’ah, Bahrain. The United States’ move to establish a permanent naval base in the Persian Gulf was a direct result of the conditions created in the aftermath of the Iran-Iraq War. Unfortunately this presence, along with U.S. naval vessels in Yemen, and combat troops in Saudi Arabia, served as the central grievance of Osama bin Laden subsequently leading to his denunciation of the West and eventually the horrific attacks of September 11, 2001.

Until the Iraq War began in 2003, the Persian Gulf was ruled by a conflicting triad anchored by Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia. The creation and provocation of the Gulf Cooperation Council among the broader regional contest with Iran, was tempered by the often-roguish behavior of the third party, Iraq. After Iraq’s initial Gulf War defeat in 1991, President George H. W. Bush’s son, President George W. Bush, was determined to remove Saddam Hussein from power and disband the Iraqi Army at the insistance of key players from within his administration.  After the ground assault on Iraq, the United States was able to quickly take control of Basrah, Nasiriyah, Najaf, and Baghdad over the span of two weeks. With the capture of Saddam Hussein and the consequent announcement ending major combat operations in Iraq, the Gulf’s localized tripolar dynamic was effectively dismantled and the United States was forced to intervene more directly in the regional balance of power. Shortly after the destruction of Iraq and its army, the United States existed in Persian Gulf with naval dominance of the waterways and air superiority over Iraq marking an interesting turn in the nature of the Gulf regional security complex, an interesting development in light of Gause’s original question about whether the United States is truly a part of the power balance in the Gulf.

After the ground assault on Iraq, the United States was able to quickly take control of Basrah, Nasiriyah, Najaf, and Baghdad over the span of two weeks. With the capture of Saddam Hussein and the consequent announcement ending major combat operations in Iraq, the Gulf’s localized tripolar dynamic was effectively dismantled and the United States was forced to intervene more directly in the regional balance of power. Shortly after the destruction of Iraq and its army, the United States existed in Persian Gulf with naval dominance of the waterways and air superiority over Iraq marking an interesting turn in the nature of the Gulf regional security complex, an interesting development in light of Gause’s original question about whether the United States is truly a part of the power balance in the Gulf.

In the wake of the Iran-Iraq War, the U.S. backing of Saudi Arabia, the dismantling of Iraq and the presence of the Fifth Fleet’s 40 ships, 175 aircraft and 21,000 personnel in Bahrain, the United States has become a critical member of the Persian Gulf security complex. Gause sums it up best when he writes “Washington is a direct, day-to-day player in Gulf politics now. Iraq is no longer a player, but a playing field.”

The Influence of U.S. Policy on Security in the Region:

The most effective faucets of U.S. policy in the Persian Gulf are manifest in military alliances with Saudi Arabia and other GCC monarchies.With a decreasing dependency on Middle Eastern oil, a continued U.S. military presence in the Gulf is required to maintain healthy relationships. In 1993 the Clinton Administration developed a strategy known as “Dual Containment,” which, in shadow of Nixon’s failed “twin pillar” strategy, formally endorsed Saudi Arabia as the premier Gulf state by limiting regional influences stemming from both Iraq and Iran. In congruence with limiting Iraq and Iran’s regional capabilities, the United States sought to reinforce GCC coalition building by selling member states, particularly Saudi Arabia, “advanced weapons” ensuring interoperability and shared training doctrine. More interestingly, the United States has been comparatively quiet with regard to voicing concern over Saudi Arabia’s efforts to obtain nuclear energy to run desalination plants. In an effort to undercut Saudi Arabia’s claim to Gulf superiority after the fall of Iraq, Iran has reached out to the smaller littoral Gulf states in an effort to establish bilateral defense agreements with the intent of siphoning off support for Saudi’s assumed increased regional responsibilities. In addition to the full backing of Saudi Arabia by American foreign policy advisors, the U.S. military has also sought a strategic foothold in the region for their own diplomatic and military missions.

Clinton Administration developed a strategy known as “Dual Containment,” which, in shadow of Nixon’s failed “twin pillar” strategy, formally endorsed Saudi Arabia as the premier Gulf state by limiting regional influences stemming from both Iraq and Iran. In congruence with limiting Iraq and Iran’s regional capabilities, the United States sought to reinforce GCC coalition building by selling member states, particularly Saudi Arabia, “advanced weapons” ensuring interoperability and shared training doctrine. More interestingly, the United States has been comparatively quiet with regard to voicing concern over Saudi Arabia’s efforts to obtain nuclear energy to run desalination plants. In an effort to undercut Saudi Arabia’s claim to Gulf superiority after the fall of Iraq, Iran has reached out to the smaller littoral Gulf states in an effort to establish bilateral defense agreements with the intent of siphoning off support for Saudi’s assumed increased regional responsibilities. In addition to the full backing of Saudi Arabia by American foreign policy advisors, the U.S. military has also sought a strategic foothold in the region for their own diplomatic and military missions.

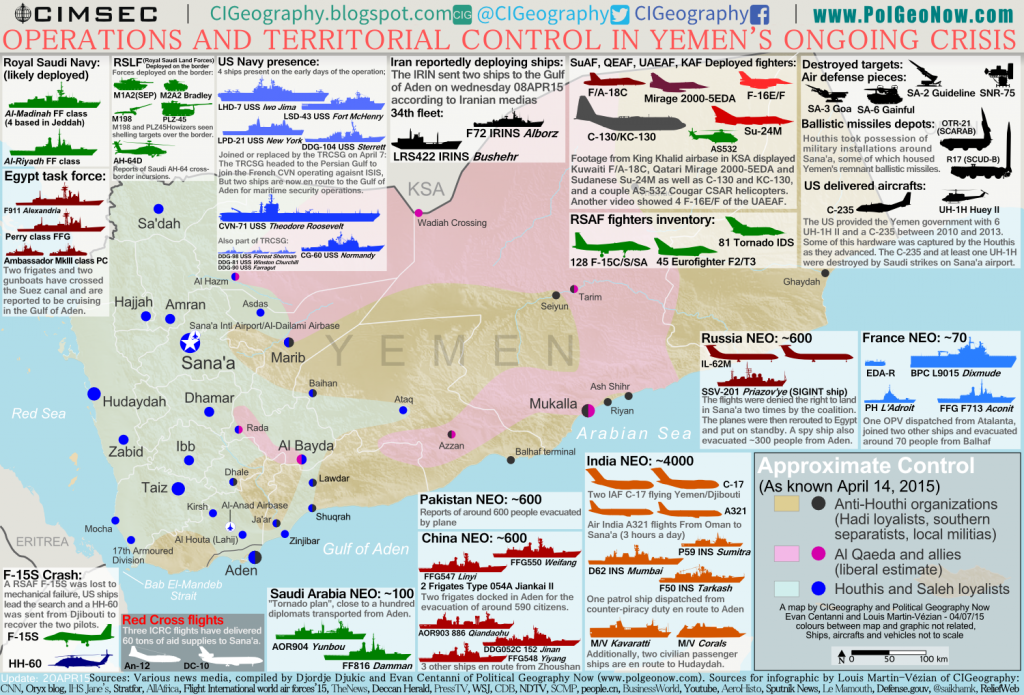

The American military plays an important role in the Persian Gulf beyond influencing regional politics. Actively patrolling the Indian Ocean and the Gulf Aden, the U.S. Fifth Fleet has undertaken the world’s responsibility of maintaining the open and free passage of the Strait of Hormuz, often under threat of blockade by Iran, and for battling Somali pirates preying on civilian tankers. In fact, the U.S. protects 17 million barrels of oil in total passing through the Strait of Hormuz everyday. Furthermore, American domestic energy policy affects the security environment in the Persian Gulf by decreasing sales, and therefore American dependency, on foreign oil. Until the end of the Bush Administration in 2009, it was forecasted that U.S. dependency on petroleum from Middle East states was on the rise. Accounting for 42% of all American oil imports, a significant portion of the 59% total from member-states of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 2005, it was forecasted in 2009 that American dependency would rise to 65% by 2020.

Conclusion:

Future diplomatic successes in the Persian Gulf will be built upon the shoulders of unofficial civilian diplomats engaged in Track II talks. Saudi, Iranian, and American non-governmental organizations can, and should, work together in tackling shared soft security challenges by capitalizing on proliferating technologies and ideas that seek to address climate change issues.

Two issues that must be resolved to increase peace and stability in the Persian Gulf are nuclear security and climate change. The weaponized use of nuclear power is a hard security issue, while climate change, and in particular water scarcity, is best characterized as a soft security issue. The word soft does not mean, however, that these issues are less important. In fact, some of the soft security issues may in fact have far greater effects on the residents of the Gulf, thus informing regional affairs in ways unaccounted for in Buzan’s regional security complex theory. Put best by Mary Luomi climate change exists as a ‘“threat multiplier” that can create or worsen intra- and interstate tensions.” Climate change’s affect on water is not limited to potable sources, but it is also driving sea levels higher, which for a country like Bahrain that depends on flood barriers, poses a serious threat. With successful collaboration in the private sector, it may just be possible to pave the road to success.

In the wake of the Iran-Iraq War and America’s Wars against Iraq in 1991 and 2003, it is clear that the Persian Gulf has faced a rapidly changing security dynamic that, to answer Gause’s original question, is underpinned by the introduction of the U.S. to the Persian Gulf regional security complex. Exhibited in the undeniable American influence in the region stemming from a full military presence, the United States has established itself as a permanent player in the Persian Gulf; a fact that will have an immense amount of influence in the foreseeable future with regard to the U.S. pivot to Asia.

Captain William Allen is a US Marine currently serving as company commander of A Co. 4th Combat Engineer Battalion, 4th Marine Division. Graduating from Columbia University’s Middle East Institute with a masters in Islamic Studies, Captain Allen is a Fellow with the Truman National Security Project and is currently serving as the Joseph S. Nye National Security Intern at the Center for a New American Security with their Technology and National Security Program. Captain Allen’s writings can be found here at the Center for International Maritime Security, as well as, the Small Wars Journal, and the International Relations and Security Network at ETH Zurich. The views expressed in his writing are his alone.

Works Cited:

Barry Buzan. Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

F. Gregory Gause, III. The International Relations of the Persian Gulf (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

J. E. Peterson. “Sovereignty and Boundaries in the Gulf States: Settling the Peripheries” International Politics of the Persian Gulf, (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2011).

Kristian Coates Ulrichsen,. Insecure Gulf: The End of Certainty and the Transition to the Post-Oil Era(London: Hurst, 2011).

Lawrence Potter. “Persian Gulf Security: Patterns and Prospects,” in Iran and the West: Regional Interests and Global Controversies, Special Report, ed. Rouzbeh Parsi and John Rydqvist (Stockholm: Swedish Defence Research Agency, March 2011).

Lawrence Potter. “The Persian Gulf: Tradition and Transformation,” Headline Series. (March 19, 2013).

Lawrence Potter. “Tripolarity” (class lecture, Security and International Politics of the Persian Gulf, Columbia University, New York, New York September 24, 2014).

Mari Luomi. “Gulf of Interest: Why Oil Still Dominates Middle Eastern Climate Politics,” Journal of Arabian Studies 1 no. 2 (2011).

Mehran Kamrava. “The Changing International Relations of the Persian Gulf,” in International Politics of the Persian Gulf, ed. Mehran Kamrava (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press)

Quadrennial Defense Review 2014. (Published by the Secretary of Defense, http://www.defense.gov/pubs/2014_Quadrennial_Defense_Review.pdf, March 4, 2014).

Unofficial U.S. Navy Site. (Published by Thoralf Doehring, http://navysite.de/navy/fleet.htm 2013).

At the core of this Gulf complex is a security rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran; a centuries old antagonism between Sunni and Shia’ Muslims manifest in global politics which now dictates defense alignment policies and military readiness. A second, and rising, security complex to examine is the establishment of the United States as a permanent military, economic, and diplomatic partner in the region – absent only in sovereign territory of its own. With the presence of the US Fifth Fleet in Bahrain, American interests in the region are clearly communicated, as are the passive-aggressive cavitation of our naval vessels plying the Straits of Hormuz at the dismay of Iran’s Supreme leader. Third, Gulf security politics exist within the broader global context of a contentious Muslim and Jewish relationship, most clearly exhibited by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. To this point, it is argued that much of the anti-Israeli rhetoric coming from Iran, for example, can be explained by recognizing Iran’s need to appear as the sole, legitimate voice of Muslims in the Gulf as opposed to Saudi Arabia. Last, this piece will address the strategic importance of an American presence in the Persian Gulf to fulfill President Obama’s pivot towards Asia. Tangled in an economic complex with the Middle East, major Pacific actors have made attempts to use their geographic back door in South Asia to secure natural resources, thus sustaining the growing trend of urbanization in Asia. Because of this, the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review calls for a continued American presence in the Gulf as a key stratagem to check expanding Chinese power.

At the core of this Gulf complex is a security rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran; a centuries old antagonism between Sunni and Shia’ Muslims manifest in global politics which now dictates defense alignment policies and military readiness. A second, and rising, security complex to examine is the establishment of the United States as a permanent military, economic, and diplomatic partner in the region – absent only in sovereign territory of its own. With the presence of the US Fifth Fleet in Bahrain, American interests in the region are clearly communicated, as are the passive-aggressive cavitation of our naval vessels plying the Straits of Hormuz at the dismay of Iran’s Supreme leader. Third, Gulf security politics exist within the broader global context of a contentious Muslim and Jewish relationship, most clearly exhibited by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. To this point, it is argued that much of the anti-Israeli rhetoric coming from Iran, for example, can be explained by recognizing Iran’s need to appear as the sole, legitimate voice of Muslims in the Gulf as opposed to Saudi Arabia. Last, this piece will address the strategic importance of an American presence in the Persian Gulf to fulfill President Obama’s pivot towards Asia. Tangled in an economic complex with the Middle East, major Pacific actors have made attempts to use their geographic back door in South Asia to secure natural resources, thus sustaining the growing trend of urbanization in Asia. Because of this, the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review calls for a continued American presence in the Gulf as a key stratagem to check expanding Chinese power. This checkers to chess dynamic is found in Southeast Asia where ASEAN states coordinate diplomatic, economic, and security interests according to a broader context of Chinese encroachment into the South China Sea. Furthermore, Buzan suggests that a security complex applies not only to states that share a region, but also implicates states that have shared economic and security goals in absence of shared borders. An example of this would be the seemingly puzzlingly and provocative rhetoric of Israeli statesmen who are factually out numbered and surrounded by opposition in the Middle East. However, when considering the added influence of American military power that backs Israel, it becomes clear that one cannot simply understand Israeli foreign policy in the region without first considering its dependent relationship upon the raw capabilities of the United States in projecting power onto countries such as Syria, Iraq, and Iran.

This checkers to chess dynamic is found in Southeast Asia where ASEAN states coordinate diplomatic, economic, and security interests according to a broader context of Chinese encroachment into the South China Sea. Furthermore, Buzan suggests that a security complex applies not only to states that share a region, but also implicates states that have shared economic and security goals in absence of shared borders. An example of this would be the seemingly puzzlingly and provocative rhetoric of Israeli statesmen who are factually out numbered and surrounded by opposition in the Middle East. However, when considering the added influence of American military power that backs Israel, it becomes clear that one cannot simply understand Israeli foreign policy in the region without first considering its dependent relationship upon the raw capabilities of the United States in projecting power onto countries such as Syria, Iraq, and Iran.

Clinton Administration developed a strategy known as “Dual Containment,” which, in shadow of Nixon’s failed “twin pillar” strategy, formally endorsed Saudi Arabia as the premier Gulf state by limiting regional influences stemming from both Iraq and Iran. In congruence with limiting Iraq and Iran’s regional capabilities, the United States sought to reinforce GCC coalition building by selling member states, particularly Saudi Arabia, “advanced weapons” ensuring interoperability and shared training doctrine. More interestingly, the United States has been comparatively quiet with regard to voicing concern over Saudi Arabia’s efforts to obtain nuclear energy to run desalination plants. In an effort to undercut Saudi Arabia’s claim to Gulf superiority after the fall of Iraq, Iran has reached out to the smaller littoral Gulf states in an effort to establish bilateral defense agreements with the intent of siphoning off support for Saudi’s assumed increased regional responsibilities. In addition to the full backing of Saudi Arabia by American foreign policy advisors, the U.S. military has also sought a strategic foothold in the region for their own diplomatic and military missions.

Clinton Administration developed a strategy known as “Dual Containment,” which, in shadow of Nixon’s failed “twin pillar” strategy, formally endorsed Saudi Arabia as the premier Gulf state by limiting regional influences stemming from both Iraq and Iran. In congruence with limiting Iraq and Iran’s regional capabilities, the United States sought to reinforce GCC coalition building by selling member states, particularly Saudi Arabia, “advanced weapons” ensuring interoperability and shared training doctrine. More interestingly, the United States has been comparatively quiet with regard to voicing concern over Saudi Arabia’s efforts to obtain nuclear energy to run desalination plants. In an effort to undercut Saudi Arabia’s claim to Gulf superiority after the fall of Iraq, Iran has reached out to the smaller littoral Gulf states in an effort to establish bilateral defense agreements with the intent of siphoning off support for Saudi’s assumed increased regional responsibilities. In addition to the full backing of Saudi Arabia by American foreign policy advisors, the U.S. military has also sought a strategic foothold in the region for their own diplomatic and military missions.