This interview originally appeared on the Small Wars Journal website and was republished with permission. You may find the interview in its original form here.

Interview with Jim Thomas (CSBA) conducted by Octavian Manea

Jim Thomas is Vice President and Director of Studies at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA). He served for thirteen years in a variety of policy, planning and resource analysis posts in the Department of Defense, culminating in his dual appointment as Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Resources and Plans and Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy. In these capacities, he was responsible for the development of defense strategy, conventional force planning, resource assessment, and the oversight of war plans. He spearheaded the 2005-2006 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), and was the principal author of the QDR report to Congress.

During the last sequences of the Cold War, the US and NATO emphasized new capabilities and new operational concepts – Assault Breaker, Air Land Battle, Follow-On Forces Attack. What role did these elements have in changing Soviet perceptions about the military balance, including restoring a credible deterrence on the NATO’s Central Front?

Four things stand out as contributing to allied success in influencing the military balance in the early 1980s.

The first and probably the most important was political: allied solidarity. The Alliance successfully deployed highly controversial systems like Pershing 2 to force the Soviet Union back to the negotiating table on intermediate nuclear forces. Showing the alliance solidarity surprised the Soviet leaders and made the situation more difficult for them. Soviet leaders had high hopes that peace movements in Western Europe would scuttle any such deal and they were dead wrong.

The second is financial: beginning in the last year of the Carter Administration and continuing into, and intensifying during the Reagan Administration, decisions were taken to increase military spending. The so-called Reagan rearmament began and continued throughout the 1980s as an effort to outspend the Warsaw Pact forces.

The third is the development of new operational concepts, the American Air Land Battle concept and NATO’s complementary Follow-On Forces Attack, which emphasized being able to hold at risk second echelon forces, to “look deep and shoot deep.”

And that leads to the fourth element: technology. A DARPA initiative called Assault Breaker that was designed to harness advanced technologies that would allow for the implementation of Air Land Battle. It was the R&D centerpiece of a new technological investment strategy and the second offset strategy launched by Harold Brown and Bill Perry during the Carter Administration focusing on three technological areas: precision warfare, low observable aircraft, and the ability to use micro-processors to create the datalinks between sensors, controllers and shooters. Assault Breaker helped to spur development of new airborne sensors, networking, stealthy strike aircraft, and precision guided munitions.

All these trends were observed in Moscow. In 1984, Marshal Ogarkov, the chief of the Soviet General Staff, acknowledged that the so-called reconnaissance strike complex was emerging and that it offered a new revolution in military affairs beyond the nuclear revolution in which conventional weaponry with precision guidance could assume some roles that were previously monopolized by nuclear forces. He was also very pessimistic about the ability of the Soviet military and its defense industry to keep pace with these developments. This military pessimism converged with also changing political currents in Moscow. It wasn’t a decisive factor, but I think it contributed to the decisions made by the Soviet political leadership in the late 1980s to seek a better relationship with the West and try to reduce military competition, which increasingly was seen as a losing proposition.

How do Russia’s contemporary A2/AD capabilities change the security landscape in Europe?

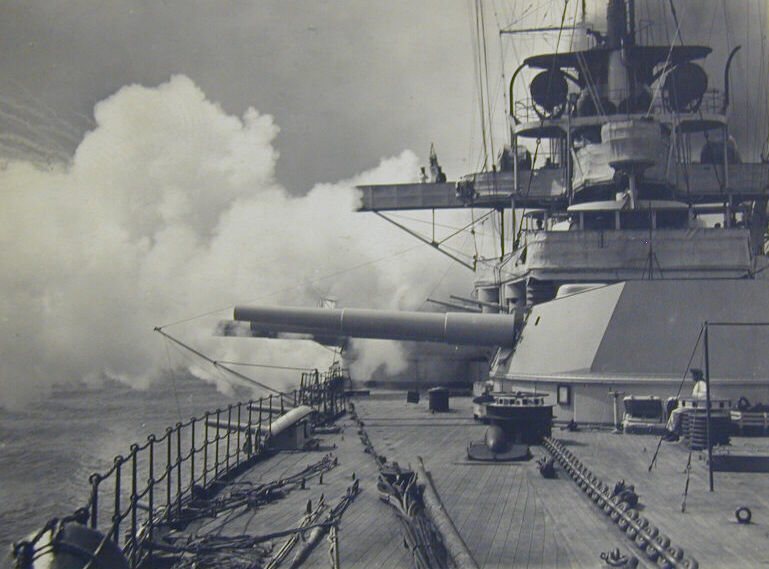

First, Russia has some very capable air and sea denial systems. Russia’s ability not only to protect its own airspace but also to deny the use of airspace over the territory of NATO frontline states in a crisis or conflict has improved dramatically. This poses real problems to the Alliance especially if NATO continues to maintain a defense in depth posture with only lightly defended frontline states.

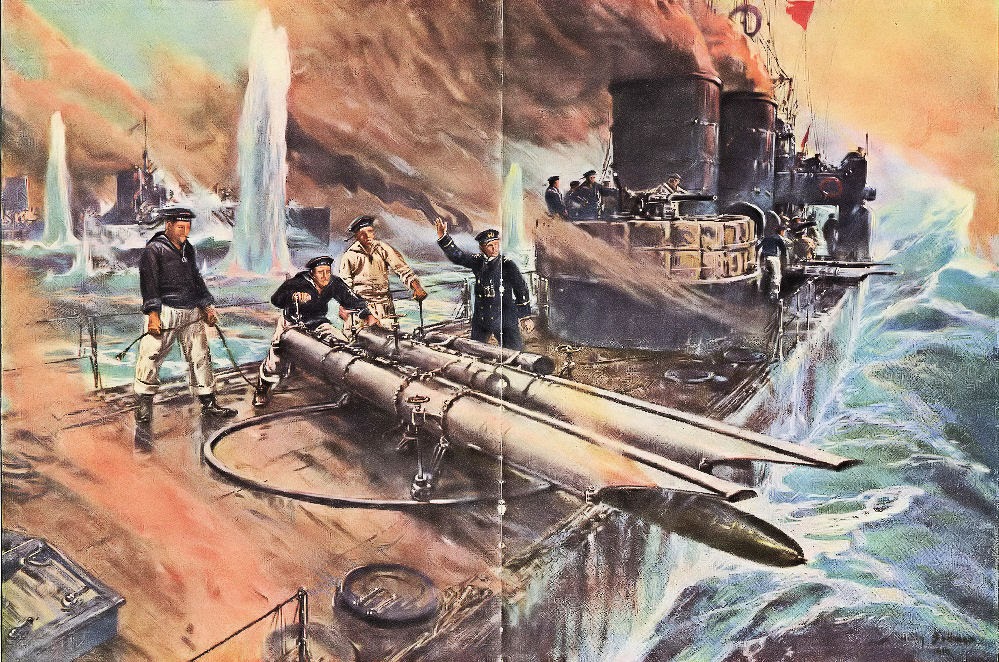

Second, since the end of the Cold War and especially since the NATO-Russia Founding Act and the adoption of the so called 3 No’s [“no intention, no plan and no reason to deploy nuclear weapons on the territory of new members”], the alliance relied on expeditionary, so-called rapid reaction forces that in a crisis or conflict would be dispatched from the more Western countries of NATO to reinforce the Eastern frontline states. But in the presence of advanced Russian air and sea denial systems this may be very difficult. In a crisis it may be in fact destabilizing to deploy NATO forces eastwards and in conflict it could be even suicidal as transport aircraft and ships, not to mention receiving ports and airbases would be vulnerable to Russian surface-to-air, anti-ship and land-attack missiles.

Third, there is this intermingling of anti-access/area denial capabilities that can essentially check conventional power-projection by other traditional militaries to reinforce frontline allies and at the same time this greater emphasis on non-linear/sub-conventional operations as emphasized by Valery Gerasimov, chief of the Russian general staff. These two types of endeavors really work hand in glove. It is this non-linear warfare area where NATO has been quite slow in terms of both defense (how it addresses these threats) as well as how it too might opportunistically exploit these similar approaches. The same can be said when it comes to A2/AD: how can the frontline states emulate or mimic some of the A2/AD approaches others are adopting to create an effective bear trap. And NATO countries also need to rethink the so called 3 NOs. It may be past time to return to a forward defense posture and permanently station US and other allied forces on the territory of the frontline states. We shouldn’t wait until the next crisis to move in this direction.

Is it accidental that revisionist powers in the Middle East, Far East and Europe are projecting their anti-status-quo interests at a time when they are feeling more confident in their own A2/AD capabilities and their ability to keep at bay traditional power projection?

Definitionally, the intention of a revisionist power is to challenge the status-quo and try to maximize its power and expand its sphere of influence. The character of revisionism is different across the three regions. Many in Europe were surprised by Putin’s annexation of Crimea because they took for granted the borders that were established at the end of the Cold War and that were perceived as indisputable as opposed to the situations in Middle East or maritime Asia.

All these revisionist powers appear less hesitant about employing irregular operations as a surrogate or as a complement to traditional military power projection. Especially when confronting other great powers, the ambiguous nature of irregular actions undertaken not by uniform soldiers, but by fishermen, by civilian protesters or by “little green men” offers a more insidious form of power projection.

Is this an incentivize for a revisionist power that had the intent, and now increasingly the capabilities and the ability, to wage low cost irregular warfare campaigns under an A2/AD umbrella?

Yes, that appears to be the case. Anti-access/area denial at the conventional level buys time and space for revisionist powers to conduct salami-slicing creeping aggression or coercion underneath whether it is in Crimea, in East China Sea, or in the future in the Middle East. Anti-access capabilities can enable conventional or unconventional forms of power projection by providing the umbrella to protect them from conventional counter-attacks especially during movements.

Rather than seeing the irregular gambit as a form of warfare distinct from conventional warfare, the revisionist powers appear to integrate these concepts in ways that combine different approaches. They are able to combine anti-access and area-denial, conventional capabilities with these irregular and sub-conventional capabilities in very effective combinations. These combinations could be differentially applied depending on the circumstances and their specific objectives at any time whether it is in Georgia, Ukraine or perhaps the Baltics or Moldova in the future. The anti-access/area-denial capabilities allow them to hold off conventional military forces and create an umbrella underneath which they can use their sub-conventional capabilities.

Do nuclear weapons have an A2/AD role? Can a nuclear umbrella play the role of an A2/AD umbrella underneath which a revisionist power can employ conventional or sub-conventional forces?

Nuclear weapons are sort of the original A2/AD threat. States that have them tend to be far more effective in dissuading others not to get too close or to think twice before attacking. Coupled with conventional A2/AD capabilities, Russia’s posture poses a vexing problem for allied planners. The range of Russia’s conventional air defense, anti-ship, and land-attack missiles blankets large portions of some frontline allies like the Baltics. Russia has declared that any attack against its territory could invite nuclear retaliation. Thus, its nuclear forces may be perceived as providing some form of sanctuary for its western conventional A2/AD capabilities.

Does NATO need a new updated 21st century Air Land Battle doctrine? How should NATO be re-postured for a security environment where parts of its territories are covered by the competitor’s A2/AD umbrella?

For NATO, the highest priority should be improving local defense of the countries on the frontline. I like Wess Mitchell and Jakub Grygiel’s proposal to establish a preclusive defense posture. Frontline states with assistance from their allies need to develop their own air, sea, land denial capabilities to negate and reduce the risks posed by the Russian conventional force aggression.

At the same time, NATO needs to develop an irregular dimension or irregular characteristics to Alliance deterrence to complement the conventional and nuclear forces. We need to expand the capacity of all NATO frontline states to conduct popular resistance, a defense that is highly irregular in its characteristics and holds out in particular a much greater risk of protracted warfare, denying quick wins for potential adversaries. We want to raise the costs dramatically for any potential aggression against NATO states and hold out the prospect of conflict widening while buying time for allies to respond and avoiding any fait-accompli on the ground. The emphasis should be put on the small highly distributed irregular resistance forces, prepositioned concealed weapons and clandestine support networks and auxiliaries. Modern guerilla forces armed with short-range man and truck portable guided rockets, guided artillery, guided mortars can conduct very rapid and very lethal maneuvers, ambushes and sabotages. We talk a lot about deterrence by denial and deterrence by punishment, but I think increasingly in the 21st century we must talk in terms of deterrence via protraction.

Should NATO have the ability to put in danger the Russian anti-access/area-denial capabilities more along the lines of the Air-Sea battle concept articulated in East Asia?

In Europe, the frontline states should make themselves indigestible and at the same time, NATO should expand its conventional strike capabilities, kinetic and non-kinetic, while preserving its nuclear options for escalation control. We want to demonstrate that there can be no possibility of aggression against NATO frontline states whether that would be classic armed conflict or would be subtle, insidious forms of subversion. We have to demonstrate unquestionable intolerance for the full range of threats that could be posed.

How should emphasis on defense modernization look like for a country like Romania exposed to the Russian A2/AD capabilities and in a time when the Black Sea is rapidly becoming a Russian A2/AD lake?

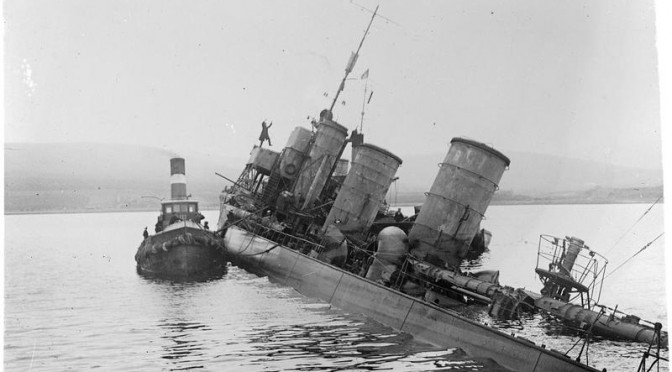

The sine-qua-non should probably be land, air, sea denial capabilities with greater emphasis on ground based air and coastal defenses, as well as distributed anti-tank weapons and mines. Romania has to return to its history and reintroduce its unique concept of popular resistance. In the long term, it may be an option to build a small fleet of coastal submarines as an asymmetric sea denial force.

This interview was published in the context of the Romania Energy Center project “Black Sea in Access Denial Age”, a project co-financed by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). To read more, go to http://www.roec.biz/bsad/