India’s Role in the Asia-Pacific Topic Week

By Ching Chang

Defining Strategic Rivalry

As we examine the issue of the Sino-India strategic rivalry, we should start from the fundamental definition of the strategic rivalry. As previous research already indicates, the strategic rivalry is concerning territorial disagreement, i.e. competing for space, or alternatively, concerning status and influence, i.e. contesting for position on the political stage. Nonetheless, the author would like to argue that three factors should be also put into consideration. There are mutually exclusive interests, explicitly stated objectives, and insignificant third-party effects. Of course, we may also interpret the third-party effects more broadly to cover any other political, economic, social, or cultural elements capable of constraining the escalation of antagonism.

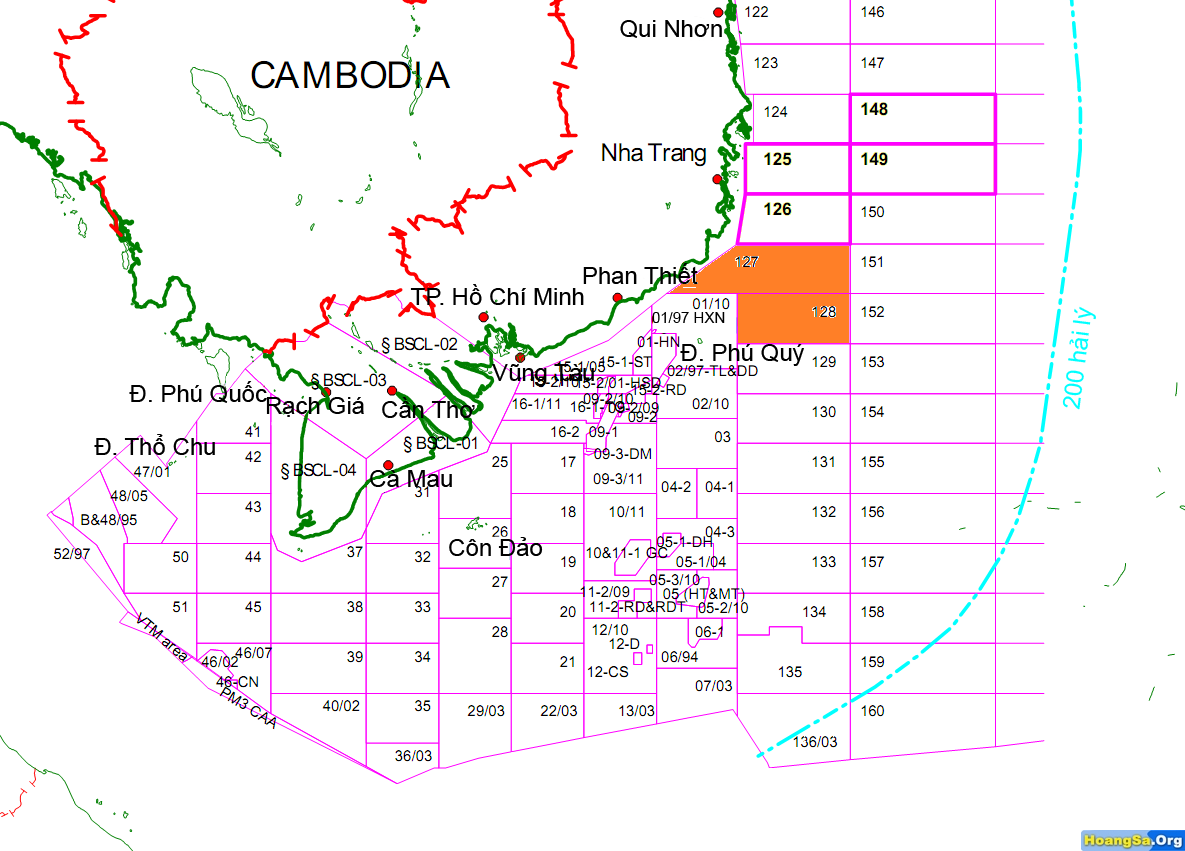

Adopting the basic definition to measure the relationship between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of India, we may clearly identify that they do have territorial disagreement along their borders. On the other hand, they also have certain degrees of competition of status as well as influence in various aspects on the world stage. Particularly, the influence within the maritime space is a key issue frequently noted by strategic commentators and political observers. Yet, how real can the general perception be? Whether the maritime competition between China and India is in the Indian Ocean or the South China Sea may prove to be only an elusive speculation though seemingly plausible.

The Myth of the Maritime Majesty

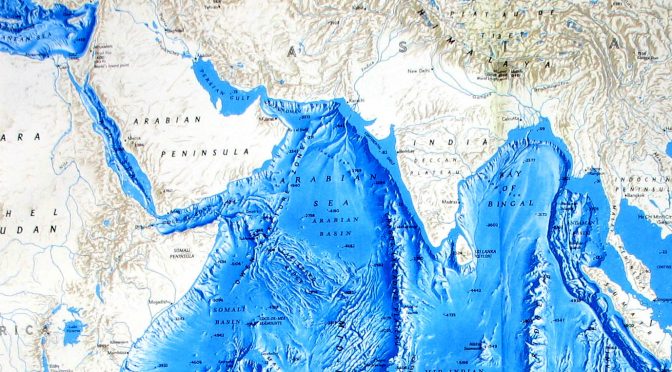

The concerns raised by the Indians accompanying the expansion of Chinese maritime presence in the Indian Ocean since early 2009 is an understandable indication of the perception of a Sino-Indian strategic rivalry in the maritime space. The excuse for Beijing to justify the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s presence in the Indian Ocean is based on the four United Nations Security Council Resolutions, Number 1816, 1838, 1846 and 1851, passed in 2008 to request and to authorize all the member states to deploy maritime forces for anti-piracy escort missions in the associated waters of the Indian Ocean. Apart from this reason, there is no other excuse ever adopted by the Chinese government to justify their routine maritime presence in the Indian Ocean though naval port visits serve diplomatic functions and joint maritime exercises do occur.

![A Chinese Navy soldier observes from a helicopter during an escort mission in the Gulf of Aden, Aug 26, 2014. This is the 18th convoy fleet sent by the Chinese People's Liberation Army Navy for these missions since 2008. [Photo/ Xinhua]](https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/002170196e1c15675f0313.jpg)

Indian strategic thinkers should consider whether the Indian position of maritime dominance in the Indian Ocean would have already been challenged or even excluded by the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s anti-piracy deployment in the region. Further, if Indian maritime forces would have the capacity to maintain the maritime majesty in the surrounding waters by assuring the safety and security of the maritime transportation as well as the peace, stability and order around the maritime theater of the Indian Ocean alone, how could the United Nations possibly passed aforementioned resolutions in 2008? Of course, the willingness to deploy People’s Liberation Army Navy forces to the Indian Ocean for committing to the United Nations resolutions is undeniably originated from the calculation of the PRC’s national interests. Nonetheless, the original aim was not intentionally to challenge or to antagonize the India’s stated supremacy of maritime dominance in the Indian Ocean.

The essence of seapower is nothing else but to support the national needs of exercising maritime activities. Among all the maritime activities generally conducted by states in the world, the utmost element is maritime transportation serving the commercial trade with other nations through various sea lanes of communication. Most states have no naval capacity of global reach to secure the security and safety of their merchant fleet, and must take a cooperative approach to support the freedom of navigation generally assured by the global maritime powers. To well control or to dominate the surrounding waters near their own territories is not practicing seapower but only conducting the defense function in the maritime domain. Conducting maritime defense function is never the core element of exercising seapower.

China needs the Indian Ocean to proceed its maritime commercial transportation. This is exactly the reason why Beijing would like to contribute to the anti-piracy escort missions defined by the United Nations Security Council resolutions. Likewise, India also needs the South China Sea to support its commercial exchanges in the East Asian region. Nonetheless, because India still needs other states to contribute their maritime forces to share the burden of maintaining the stability and security in the Indian Ocean, how can New Delhi justify its decision to send maritime forces to the waters in the East Asian region and form an atmosphere of maritime strategic rivalry with China in the South China Sea? Particularly, it is hard to get any resolution from the United Nations Security Council whilst the freedom of navigation for maritime commercial transportation is never substantially affected so far, no matter how loud anyone ever decries the maneuvers in the South China Sea.

For any Indian strategist who would like to advocate the unnecessary aspiration of expanding the Indian naval presence to the South China Sea, they should ask how such a decision may serve Indian strategic interests. They should scrutinize whether there is any mutually exclusive interests between China and India in the maritime space, either in the Indian Ocean or in the South China Sea. Further, if Indian strategists insist a strategic rivalry in the maritime theater is inevitable between Beijing and New Delhi, at least, these strategists should list those explicitly existed objectives as the basis for their advocacy. The same rule may also apply to over-enthusiastic strategic thinkers in Beijing. If both sides cannot clearly identify what exactly they may fight for, then how can a strategic rivalry in the maritime space be a realistic assumption? The key of solving the strategic challenge requires finesse. Fighting with a nonexistent strategic rivalry in mind like Don Quixote may only propagate foolhardiness.

Defusing the Land Territory Antagonism

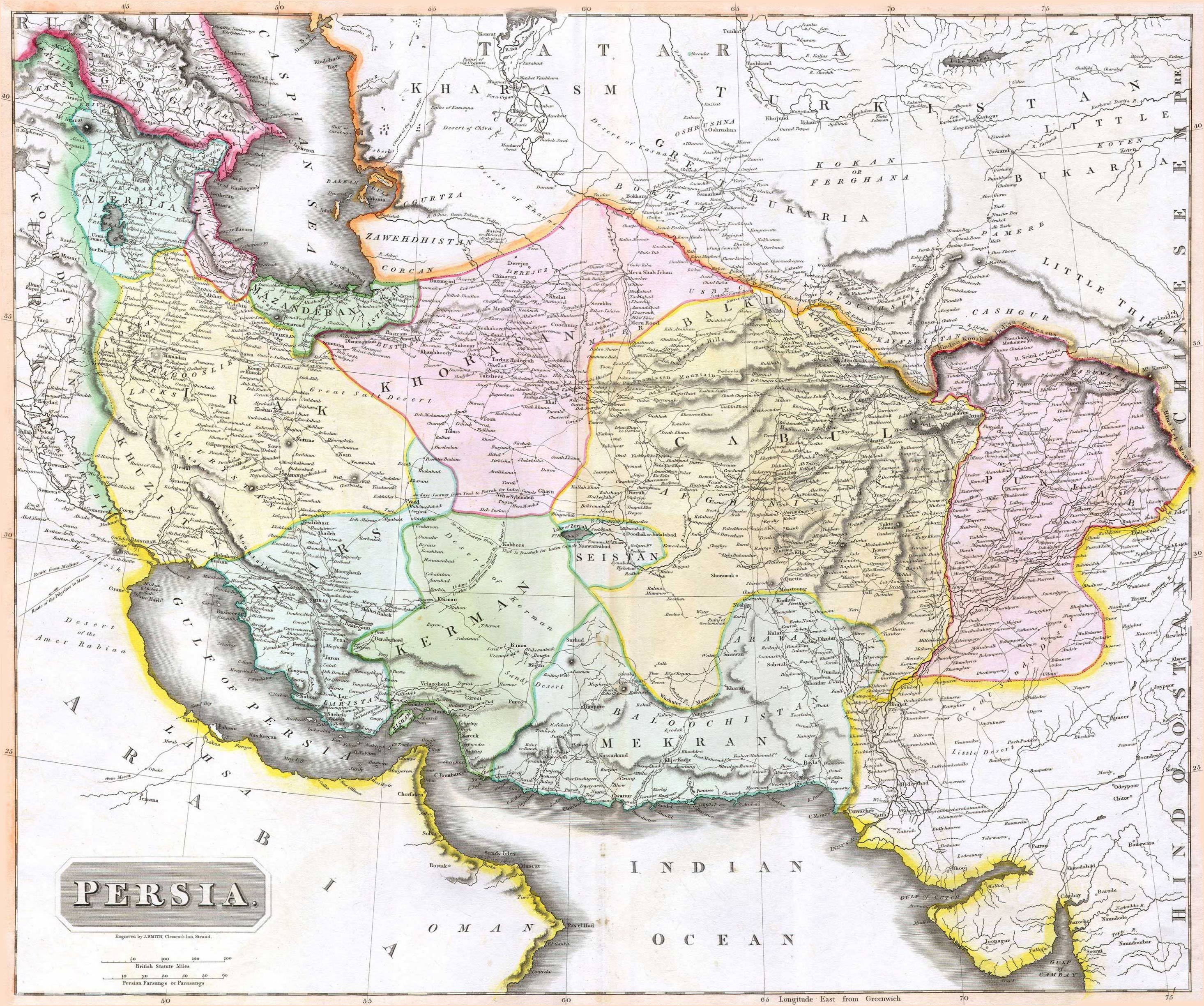

Comparing abstract and elusive maritime contention, there are concrete and substantial territorial disputes along the borders between India and China. Could the territorial disagreement be a good reason to justify the strategic rivalry between these two traditional land powers separately existed in East Asia and South Asia? The territorial dispute does satisfy the three aforementioned criteria. It involves mutually exclusive interests and the territories themselves involve explicitly stated objectives. Given there is no other comparatively powerful states involved in their border disputes, the third-party effect is insignificant. Nonetheless, the possibility of finding a key for solving the seemingly rivalry still exists.

If we review all the factors involved in the territorial disputes between Beijing and New Delhi, the most irrelevant and misleading element that should be taken away from strategic calculation is the argument originating from the McMahon Line. The McMahon Line is unilaterally regarded by India as the border-should-be with China. Nonetheless, the McMahon Line and the Simla Accord may not survive an inspection of criterion existing in international judiciary practices.

The Chinese civilization engaged with the Indian civilization for thousands of years prior to the western presence in the sub-continent. Many cultural features introduced from India are still actively practiced in China today and have been openly admitted by the Chinese. The legacy of Indian influence is clearly indicated in many Chinese historical sites. However, the insistence of the McMahon Line is in essence an insult. It is a legacy left by the colonists in India never recognized by the Chinese. Insisting the order defined by the western colonists along the border of these two ancient civilization, is indeed a confession of no confidence.

The McMahon Line is an indication that two ancient civilizations failed to set the order by themselves but need to rely on western civilization to define it for them. The possibility of the Chinese accepting an arrangement with such significance is extremely slim. To insist the McMahon Line as the basis for demarcation only proves that western civilization still effectively colonizes the strategic thinking in the Indian security professional community. Especially since the heritage left by the British colonists is fundamentally controversial. If India has no intention to let their strategic calculation be released from such a misleading shackle, then what is the value of getting independence in the late 1940s?

The author would like to recommend that Indian strategic thinkers conduct a survey on those successful cases of demarcation on land borders between Beijing and all its neighboring states except India in the past few decades. The most important lesson to be concluded from these cases is that any compromise on demarcation should be a decision made by the people actually involved now, not by a former colonial master. In many cases of these demarcation negotiations, Chinese negotiators have reasonably accepted the realities such as when former PRC Prime Minister Zhou Enlai pragmatically recognize the Line of Actual Control in a 1959 diplomatic note. To understand the modus operandi of Beijing is the essential element for defusing the disputes along their borders.

Indian strategic thinkers should consider establishing a demarcation line between these two civilizations with an Indian or a Chinese name but not from a British official once colonized India. Unless keeping the territorial disputes unsettled may still serve the Indian interests, otherwise, it is about the time the Indian strategic community set itself free from the myth of the McMahon Line. By adopting the yardsticks of “cui bono” and “cui malo” the strategic thinkers of these two great civilizations should be able to draw a demarcation line between them with a name they may agree to choose for glorifying their cultural wisdoms.

Chang Ching is a Research Fellow with the Society for Strategic Studies, Republic of China. The views expressed in this article are his own.