By Ryan Martinson

Today, Chinese underwater gliders operate throughout the Indo-Pacific, from the Bay of Bengal to the Bering Sea, from high seas to sovereign waters. These winged, torpedo-like submersibles are being deployed in droves to collect information about the marine environment. Traveling underwater in a vertical sawtooth pattern, gliders use onboard sensors to measure characteristics of the ocean such as temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, and current speed at different depths to generate water column profiles. This data indirectly bolsters the capabilities of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) by expanding its tactical understanding of the ocean environment.

Scientists and engineers based in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) are also developing a new generation of gliders that could play a far more direct role in naval combat by detecting enemy submarines. Since 2014, experts at the PLAN Submarine Academy, working with colleagues at civilian institutions, have been equipping Chinese gliders with passive acoustic sensors. Chinese language records of their activities show a determined effort to adapt this technology for anti-submarine warfare (ASW), an enduring weakness for the PLAN—one that, if remedied, could shake U.S. conventional deterrence in the Western Pacific.

Why Gliders?

The PLAN has a very difficult time detecting advanced foreign submarines within Chinese-claimed maritime space. Modern submarines are stealthy, the ocean is vast and complex, and ASW is inherently difficult—for any navy. But the stakes are especially high for China, given the perceived threat that foreign submarines pose to China’s maritime security. PRC experts often lament that China’s “underwater front door is wide open” (水下国门洞开). China’s 13th Five Year Plan for Innovation in Marine Science and Technology frankly admitted that China “still lacks the ability to resist hostile threats from the deep sea.” One PLAN analyst declared, “the threats our country faces in the maritime direction mainly come from the undersea [domain], and the main gap with the powerful enemy [the U.S.] is also in the undersea [domain].”

To shrink this capability gap, the PRC has invested heavily in new ASW capabilities for its fleet while looking to the U.S. Navy as a model. The PLAN has built ocean surveillance vessels like the USNS Effective to tow acoustic sensors designed to detect submarines. The PLAN has also procured sub-hunting maritime patrol aircraft, similar to the U.S. Navy’s P-3 “Orion,” and it may soon begin equipping the fleet with an ASW variant of the Z-20 helicopter, often described as a close copy of the MH-60 “Seahawk.”

The PRC is also taking steps to build a network of sensors, some mobile and some fixed, to detect foreign submarines in operationally important areas. Together, these sensors would constitute an “undersea alert system” (水下警戒体系). Some ASW platforms use traditional hydrophones, which only capture information about the frequency (hertz) and intensity (decibels) of sound. However, to localize the source of the sound, multiple hydrophones are often combined into an array, which can be large and unwieldy. A single vector sensor, in contrast, is capable of determining the direction of a sound source. China is very keen on pursuing a new generation of piezoelectric vector sensors, which are far smaller than previous types. Their compact size also allows their installation on much smaller platforms like underwater gliders.

Gliders move up and down in the water column by adjusting their buoyancy while their “wings” enable them to move forward at an angle. As ASW platforms, gliders offer several advantages. Due to their low power requirements, some gliders can operate at sea for months at a time. Because of the simplicity of their design, gliders are also comparatively cheap—an important attribute since they must be deployed in large numbers to be effective. Unlike fixed undersea sensors, gliders can move to where they are needed (albeit very slowly, at just about one knot). Lastly, gliders can maintain regular communications with their operators by transmitting their location (and other information) and receiving new commands when they surface at the end of a dive.

How might the PLAN use acoustic gliders? According to the PLAN researchers working on the project discussed in this article, they would be used to “complete tasks such as autonomous detection, tracking, attribute discrimination, and sending back information on moving targets in sensitive waters or areas of denial (拒止区域).” The program director, Rear Admiral Da Lianglong, likened them to a front-door “security system” (安保系统). One of his briefing slides from a 2019 presentation suggests that the PLAN intends to deploy them in the relatively quiet, deeper waters of the Philippine Sea and northern South China Sea, operationally-important areas where China lacks islands to build fixed undersea arrays.

The Dolphin Project

While the advantages of gliders seem obvious, there are also many technical challenges that must be overcome before they can be used in ASW. Since 2014, the PLAN Submarine Academy, working in conjunction with scientists and engineers from Tianjin University and the Qingdao Pilot National Lab for Marine Science and Technology have methodically surmounted many of these challenges and now possess a capable prototype glider, the “Dolphin,” which has already undergone several rounds of testing in the South China Sea.

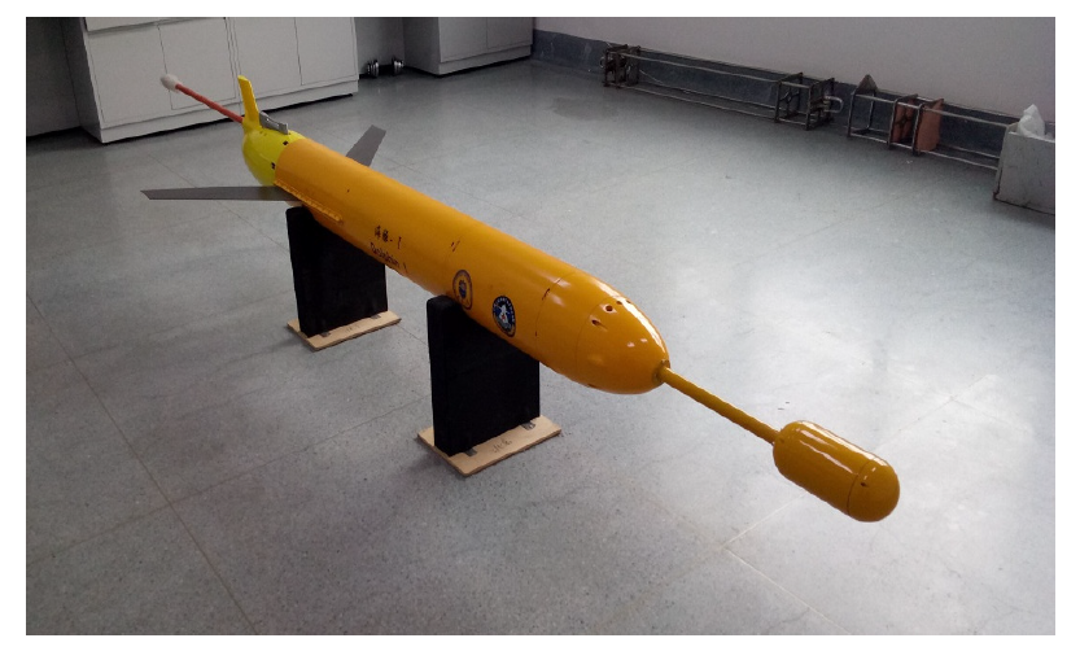

The Dolphin is based on the Haiyan glider developed by researchers at Tianjin University. Like most sea gliders, the Haiyan is a tubular robot with wings and a visible antenna. However, it is somewhat unusual in that it is equipped with a small propeller, a useful feature if needed to surface quickly in the event of a potential submarine contact. Chinese oceanographers have already deployed Haiyan gliders within the first island chain and beyond. A specially designed Haiyan variant (Haiyan-X) is capable of diving to tremendous depths, including the bottom of the Mariana Trench. Another variant (Haiyan-L) has been built for greater endurance, purportedly up to five months of continuous operations.

The Dolphin looks like a typical Haiyan glider, except for a vector sensor protruding from its nose. Within the body of the glider, forward of the batteries, is its signal processor. indicating that the platform is designed to autonomously detect, classify, and locate undersea targets, not merely to record and transmit raw data for interpretation elsewhere.

The Dolphin project is led by the Naval Undersea Warfare Environmental Research Institute (海军水下作战环境研究所) at the PLAN Submarine Academy. It is overseen by the Institute’s Director, Rear Admiral Da Lianglong, perhaps the PLAN’s most accomplished expert on undersea science and technology. Rear Admiral Da has won numerous national, provincial, and military awards for his work on how the undersea environment affects sonar performance and submarine tactics.

Under Rear Admiral Da’s leadership, the Environmental Research Institute has shrewdly leveraged civilian organizations to help advance its mission. In 2013, his institute turned its attention to vector sensors. Then, in 2016, it joined with the Qingdao Pilot National Lab for Marine Science and Technology to create the Joint Lab for Civil Military Integration in Qingdao, with Rear Admiral Da as its director. This allows the Submarine Academy to benefit from the expertise, access, and resources available to the civilian marine science community. When Xi Jinping visited the Qingdao Pilot National Lab in June 2018, he spoke about the importance of civil-military integration in marine science. Rear Admiral Da stood beaming in the audience, the embodiment of Xi’s ideal.

Milestones

The team at the Submarine Academy overcame several technical challenges to make the Dolphin a viable ASW platform including self-noise, contact localization fidelity, and overcoming the immense pressure water pressure of deep dives.

The first was self-noise. Researchers originally built the Haiyan glider for oceanographic research, where self-noise is far less of a concern. However, when detecting submarines, it is vital that an ASW platform be as quiet as possible to make it easier to distinguish the relevant signatures from other noises and thereby maximizing the signal to noise ratio. This is especially important when that signature is extremely faint, like those emitted by modern submarines.

The Haiyan produces noise at the bottom of its dive, when a pump activates to increase buoyancy needed for the ascent. It also produces noise when the propeller engages. These noise problems, however, are simple fixes since the glider can be programmed to turn off its vector sensor during the brief periods when the pump and propeller are on. For the Chinese researchers, the real challenge was reducing the noise generated by the mechanisms used to maintain the glider’s course and attitude. Researched overcame this challenge by changing the position of the glider’s internal battery packs. Through a series of tests conducted at first in specially designed pools followed later by tests in the South China Sea, the researchers were able to optimize attitude and course adjustment mechanisms to reduce this self-noise.

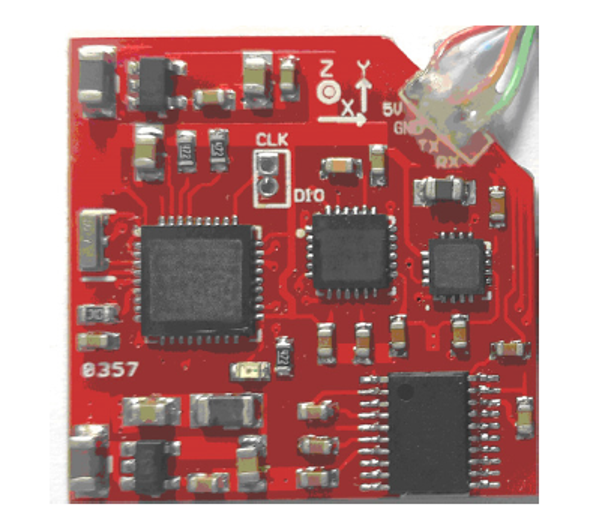

Slight changes to the attitude of the glider presented a second challenge that had to be overcome: errant localization. The vector sensor receives data about the direction of a target in relationship to the attitude of the sensor at the time of detection. For this information to be tactically valuable, the glider required a tiny attitude sensor that would enable an onboard computer to locate the target relative to the surface of the ocean. Scientists at the PLAN Submarine Academy, including Da Lianglong himself, successfully developed a sensor for this purpose and it now equips the Dolphin glider.

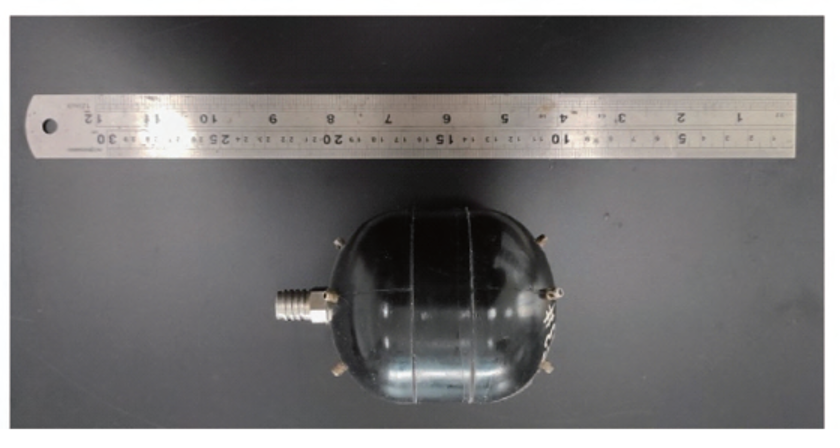

Finally, Chinese scientists also had to develop a vector sensor that could reliably operate in the high-pressure environment of the deep ocean. Since many countries prohibit the sale of acoustic sensors to China, researchers could not simply import a foreign product. Since the early 2000s, experts at Harbin Engineering University have conducted pathbreaking research on vector sensors. The team at the Submarine Academy built off their work to develop a deep water vector sensor. In 2019, researchers tested the new sensor in the South China Sea at depths of 800 meters and 1,200 meters with promising results. That same year, Rear Admiral Da and several other colleagues at the Submarine Academy patented a vector sensor that could effectively operate down to 4,000 meters. According to their patent application, the sensor could be particularly suited for unmanned platforms like gliders “for use in submarine detection.”

Since 2018, the Dolphin has undergone multiple tests in the South China Sea, in the deep water northwest of the Paracel Islands. To date, Chinese researchers have only tested the glider’s ability to detect surface ships, which are obviously much louder than submarines. Two series of tests conducted in May and June of 2018 focused on reducing self-noise. Since then, the team has sought to refine the capabilities of the glider’s onboard systems. The most recent known tests conducted in January of 2020 offer a gauge of the Dolphin’s current capabilities. They also show the scale of the PLAN’s commitment to developing these platforms.

During the January 2020 tests, a Dolphin glider successfully tracked the movements of a 50 meter research ship (Haili) traveling at 8 knots at a maximum range of 6.5 km. As part of the same series of tests, a Dolphin glider also tracked a 60-meter merchant ship traveling at 11.7 knots at a maximum range of 11.4 km. The Dolphin also tracked the movements of a 192-meter container ship traveling at 15 knots at a maximum range of 11.2 km. Additionally, in January of 2020, a Dolphin glider tracked a 99-meter rescue and salvage ship, the Nanhaijiu 116, steaming at 14 knots at a maximum detection range of 14.4 km.

Next Steps

To be effective, a glider like the Dolphin would need to work in concert with other such platforms. A single glider would not be enough, since detection ranges will be very short and gliders are not very mobile. The PLAN will likely want to fill an operationally important area of the ocean with dozens of gliders, which will need to be coordinated to ensure efficient coverage. This will be further complicated by the fact that gliders, due to their slow speeds, are vulnerable to undersea and surface currents. Therefore, if one glider drifts out of a given area, another glider will need to move in to fill the gap. Researchers at the Submarine Academy and the Qingdao Pilot National Lab already completed simulations to address the challenge of optimizing the deployment of multiple gliders for target detection. However, these efforts have not yet been tested at sea.

Another challenge is autonomy in signal processing. Gliders will need to analyze the raw acoustic data they receive and determine if what they are “hearing” contains the signature of a target of interest. That task is fairly easy if the target is a 190-meter commercial ship traveling at 12 knots. But it becomes extremely difficult when it is a modern submarine operating at slow speed in the noisy waters of the South China Sea. Detecting and classifying targets has traditionally required humans (i.e., sonar technicians) in the loop. Developing systems that can mimic human intelligence will be vital for any autonomous ASW platform, and Chinese experts have been working on this problem for years, again, most notably at the Harbin University of Engineering. Researchers there claim they have developed unmanned platforms capable of autonomously detecting surface and undersea targets at long range and have tested them in lakes and at sea. In October 2018, the University signed a cooperative agreement with the Submarine Academy, although it remains uncertain if this will include collaboration on underwater gliders. In the meantime, researchers from the PLAN Submarine Academy and the Qingdao Pilot National Lab are proceeding with their own efforts to improve autonomy in target detection.

This relates to another huge challenge of filtering out false detections. Failing to detect an enemy submarine is bad, but declaring the presence of an enemy submarine where none exists could be potentially worse for the PLAN. It might deploy manned ASW assets to the area of false contact, wasting time and resources. Acoustic gliders will likely not be deployed for real-world operations until the PLAN is reasonably certain that onboard systems are sophisticated enough to keep false detections to an absolute minimum. In this situation, redundancy in the undersea alert system (i.e., many sensors in a given area) could help strengthen confidence in a target detection.

Conclusion

Writing in early 2013, before substantive work on acoustic gliders began in China, an expert at the 710 Research Institute boldly predicted—in his words, “without the least bit of exaggeration”—that the future development of underwater gliders would leave submarines with “no place to hide” (无处遁形). Almost ten years later, the PRC is still nowhere close to that. However, the PLAN has come a long way in a short period of time. This achievement has been made possible through a talented, dedicated, and well-funded research team at the PLAN Submarine Academy, a successful approach to civil-military integration, and institutional commitment to redressing China’s weaknesses in ASW. China now possesses a viable prototype acoustic glider that has undergone multiple rounds of testing in the South China Sea. China clearly intends to shut its “underwater front door,” and acoustic gliders will be one tool that helps it do just that.

Ryan D. Martinson is a researcher in the China Maritime Studies Institute at the Naval War College. He holds a master’s degree from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University and a bachelor’s of science from Union College. Martinson has also studied at Fudan University, the Beijing Language and Culture University, and the Hopkins-Nanjing Center.

Featured Image: The guided-missile frigate Zhoushan (Hull 529), together with the guided-missile destroyers Taizhou (Hull 138) and Hangzhou (Hull 136), steam to designated sea area in East China Sea during a maritime training exercise in early January, 2021. (eng.chinamil.com.cn/Photo by Liu Yaxun)