By Ben Ho Wan Beng

Introduction

“Unmanned aviation” has been a buzzword in the airpower community during recent years with the growing prevalence of unmanned systems to complement and in some cases replace peopled ones in key roles like intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR). Insofar as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are increasingly used for strike, their dominant mission is still ISR because of the fledging state of pilotless technology. This is especially the case for sea-based drones, which are generally less capable than their brethren ashore. That said, several littoral navies have jumped on the shipborne UAV bandwagon owing to its relative utility and cost-effectiveness.[1] And with access to such platforms, how would these entities be affected during combat?

For littoral nations without an aerial maritime ISR capability in the form of maritime patrol aircraft (or only having a limited MPA capability), the sea-based drone can make up for this lacuna and improve battlespace/domain awareness. On the other hand, for littoral nations with a decent maritime ISR capability, the shipborne UAV can still play a valuable, albeit, complementary role. The naval drone also offers the prospect of coastal forces amassing more lethality as it refines the target-acquisition process, enabling its mother ship to attack the adversary more accurately.

The Littoral Combat Environment

Littoral operations are likely to be highly complex affairs. As esteemed naval commentator Geoffrey Till said: “The littoral is a congested place, full of neutral and allied shipping, oil-rigs, buoys, coastline clutter, islands, reefs and shallows, and complicated underwater profiles.”[2] One key reason behind the labyrinthine nature of littoral warfare is that it involves clutter not only at sea, but also on land and in the air. Especially troublesome is the presence of numerous ships in the littorals. To illustrate, almost 78,000 ships transited the Malacca Strait, one of the world’s busiest waterways, in 2013.[3]

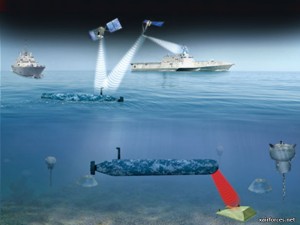

Such a complex operating milieu would place a premium on the importance of battlespace awareness, which could make or break a campaign. As fabled ancient Chinese military philosopher Sun Tzu asserted: “With advance information, costly mistakes can be avoided, destruction averted, and the way to lasting victory made clear.” This statement was made over 2,000 years ago and is still as relevant today, especially when considered against the intricacies of littoral combat that hinder sensor usage. Indeed, shipborne radar performance during littoral operations can be significantly degraded by land clutter. For instance, the 1982 Falklands conflict manifested the problems sea-based sensors had in detecting and identifying low-flying aircraft with land clutter in the background.[4] Campaigning in congested coastal waters would also necessitate the detection and identification of hostile units in the midst of numerous other sea craft, which is by no means an easy task. All in all, the clutter common to littoral operations presents a confusing tactical picture to naval commanders, and the side with a better view of the situation – read greater battlespace awareness – would have a distinct edge over its adversary. Sea-based UAVs can provide multispectral disambiguation of threat contacts from commercial shipping by virtue of onboard sensor suites, yielding enhanced situational awareness to the warfare commander.

Improved Battlespace Awareness

Traditional manned maritime patrol aircraft (MPA) would be the platform of choice to perform maritime ISR that helps in raising battlespace awareness in a littoral campaign. However, not all coastal states own such assets, which can be relatively expensive[5], or have enough of them to maintain persistent ISR over the battlespace, a condition critical to the outcome of a littoral operation. This is where the sea-based drone would come in handy. Unmanned aviation has a distinct advantage over its manned equivalent, as UAVs can stay airborne much longer than piloted aircraft. To illustrate, the ScanEagle naval drone, which is in service with littoral navies such as Singapore and Tunisia and commonly used for ISR, can remain on station for some 28 hours.[6] In stark contrast, the corresponding figure for the P-3 Orion MPA is 14 hours.[7] The sensor capabilities of some of the naval drones currently in service make them credible aerial maritime ISR platforms. Indeed, they are equipped with sophisticated technologies such as electro-optical and infrared sensors, as well as synthetic aperture radar (SAR) systems.

To be sure, the shipborne UAV is incomparable to the MPA vis-à-vis most performance attributes, and the two platforms definitely cannot be used interchangeably. The utility of the naval drone lies in the fact that it can complement the MPA by taking over some of the latter’s routine, less demanding surveillance duties. This would then free up the MPA to concentrate on other, more combat-intensive missions during a littoral campaign, such as attacking enemy ships. And for a littoral nation without MPAs, the shipborne UAV would be especially valuable as it can perform aerial ISR duties for a prolonged period.

The naval drone can contribute to information dominance in another way. In combat involving two littoral navies, the side with organic airpower tends to have better domain awareness over the other, ceteris paribus. However rudimentary it may be, the shipborne drone constitutes a form of organic sea-based airpower that extends the “eyes” of its mother platform. The curvature of the Earth limits the range of surface radars, but having an “eye in the sky” circumvents this and improves coverage significantly. Being able to “see” from altitude allows one to attain the naval equivalent of “high ground,” that key advantage so prized by land-based forces. Indeed, the ScanEagle can operate at an altitude of almost 5,000 meters.[8] In the same vein, the Picador unmanned helicopter has a not inconsiderable service ceiling of over 3,600m.[9] In essence, the UAV allows its mother ship to detect threats that the latter would generally be unable to using its own sensors.

All in all, shipborne drones enable littoral fleets to have a clearer tactical picture, translating into improved survivability by virtue of the greater cognizance of emerging threats that they offer to surface platforms. Having greater battlespace awareness also means that the naval force in question would be in a superior position to dish out punishment on its adversary.

Increased Lethality

Sea-based UAVs would enable a littoral navy to target the opposing side more accurately as they can carry out target acquisition, hence increasing their side’s lethality. In this sense, the drone is reprising the role carried out by floatplanes deployed on battleships and cruisers in World War Two. During that conflict, these catapult-launched aircraft acted as spotters by directing fire for their mother ships during surface engagements. In more recent times, during Operation Desert Storm, Pioneer UAVs from the American battleship Wisconsin guided gunfire for their mother ship. Several current UAVs can fulfill this role. For instance, the Eagle Eye can be used as a guidance system for naval gunfire; ditto the Picador with its target-acquisition capabilities. There is also talk of drones carrying out over-the-horizon targeting so as to facilitate anti-ship missile strikes from the mother platforms.[10]

Though land-based UAVs are increasingly taking up strike missions, the same cannot be said for their sea-based counterparts as very few of the latter are even in service today in the first place due to their complexity and cost. The Fire Scout is one such armed naval UAV. This United States Navy rotorcraft can be armed with guided rockets and Hellfire air-to-surface missiles; however, with a unit cost of US$15-24 million[11], it is not a low-end platform. All in all, unarmed shipborne drones are likely to be the order of the day for littoral navies, at least in the near term, and such platforms can only carry out what they have been doing all this while, tasks like ISR and target acquisition.

Conclusion

In summary, the sea-based drone can, to some extent, complement the maritime patrol aircraft in the aerial ISR portfolio at sea by helping to maintain battlespace awareness for the littoral navy during a conflict. The naval UAV’s target-acquisition capability also means that it can improve its owner’s striking power to some extent. These statements, however, must be qualified as current shipborne drones can only operate in low-threat environments – in contested airspace, their survivability and viability would be severely jeopardized, as they are simply unable to evade enemy fighters and anti-aircraft fire. In the final analysis, it can perhaps be maintained that the rise of sea-based UAVs constitutes incremental progress for littoral navies, as the platform does not offer game-changing capabilities to these entities.

Going forward, ISR is likely to remain the main mission for sea-based drones in the near future. Though the armed variant seems to offer a breakthrough in this state of affairs, it must be stressed that it is neither a simple nor cheap undertaking. If and when defense industrial players provide lower-cost solutions to this issue in the future, however, the striking power of coastal fleets would increase considerably and with that, the nature of littoral and naval warfare in general would profoundly change. Until then, the sea UAV-littoral navy nexus will be characterized by evolution, not revolution.

Ben Ho Wan Beng is a Senior Analyst with the Military Studies Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore; he received his master’s degree in strategic studies from the same institute. The ideas expressed above are his alone. He would also like to express his heartfelt gratitude to colleague Chang Jun Yan for his insightful comments on a draft of this article.

This article featured as a part of CIMSEC’s September 2015 topic week, The Future of Naval Aviation. You can access the topic week’s articles here.

Endnotes

[1] For instance, the Scan Eagle drone has a unit cost of $100,000. See www.nytimes.com/2013/01/25/us/simple-scaneagle-drones-a-boost-for-us-military.html?_r=0.

[2] Geoffrey Till, Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-first Century (London: Routledge, 2013), 268.

[3] Marcus Hand, “Malacca Straits transits hit all-time high in 2013, pass 2008 peak,” Seatrade Maritime News, February 10, 2014, accessed September 4, 2015, www.seatrade-maritime.com/news/asia/malacca-straits-transits-hit-all-time-high-in-2013-pass-2008-peak.html.

[4] Milan Vego, “On Littoral Warfare,” Naval War College Review 68, No. 2 (Spring 2015): 41.

[5] Some of the more common MPAs include the P-3 Orion, which is in service with nations like New Zealand and Thailand which has a unit cost of US$36 million, according to the U.S. Navy. See www.navy.mil/navydata/fact_display.asp?cid=1100&tid=1400&ct=1.

[6] “ScanEagle, United States of America,” naval-technology.com, accessed September 5, 2015, www.naval-technology.com/projects/scaneagle-uav.

[7] “P-3C Orion Maritime Patrol Aircraft, Canada,” naval-technology.com, accessed September 5, 2015, www.naval-technology.com/projects/p3-orion.

[8] “ScanEagle, United States of America.”

[9] “Picador, Israel,” naval-technology.com, accessed September 5, 2015, www.naval-technology.com/projects/picador-vtol-uav.

[10] Martin Van Creveld, The Age of Airpower (New York: Public Affairs, 2012), 274.

[11] United States Government Accountability Office, Defense Acquisitions: Assessment of Selected Weapons Program, March 2015, 117.