By Dmitry Filipoff

Last week CIMSEC ran a special series of short notes to commemorate the first anniversary of the Warfighting Flotilla. In the Flotilla, warfighters and navalists come together to discuss naval warfighting, force development, and the naval profession. Over the course of its first year, this new naval professional society grew to more than 300 members and hosted dozens of virtual discussions on naval force development. Visit the Flotilla homepage to join our growing membership and learn more about this community, its activities, and what drives it.

Flotilla members submitted their thoughts on how to improve naval tactical learning and force development. From wargaming courses to enhanced combat training, these recommendations can help navalists and warfighters define opportunities to improve tactical excellence.

We thank these authors for their contributions, listed below.

“The Navy Must Redefine Risk in Combat Training,” by Tom Clarity

“It is easy to put safety measures in place to prevent slips and falls, or to limit the minimum lateral separation of two aircraft at the merge. It is far harder to consider what risks are additive to the Navy’s overall warfighting readiness, but it is a crucial source of developing warfighting advantage.”

“The Cost of Delaying Wartime Tactical Adaptation,” by Jamie McGrath

“To rapidly assess and implement tactical adaptation based on combat lessons, the Navy must prioritize staffing its warfighting development centers in wartime, even if it means leaving some shipboard billets unfilled. Failure to rapidly capture, disseminate, and assess lessons from early combat will result in costly losses to our surface force before we can adjust to the character of the current war.”

“Building Sailor Toughness and Combat Mindset: What worked on USS JOHN S. McCAIN and USS VICKSBURG,” by Charles “Chip” Swicker

“When a team trains like a team and looks like a team, the energy really resonates with Sailors. Combat is a team sport. Train your Sailors with a stopwatch, and coach them toward a goal of flawless execution at speed. Train them day or night, rested or tired, so that their muscle memory carries them through in the confusion and terror of an actual sea fight.”

“Bring Back the Warfighting Flash Cards,” by Alan Cummings

“Like any learning resource, these flash cards are a tool—one that offers deckplate leaders a tangible and flexible way to cultivate warfighting mindset and know-how. It will depend on unit commanders and their subordinate leaders to make use of it.”

“Starting with a Step: Creating Professional Incentives for Continuous Tactical Learning,” by Benjamin Clark

“A culture of constant learning according to the practicing naval tacticians’ own analysis of necessity of deeper research, learning, and exploration of the aspects of warfare will naturally lead to a stronger understanding and application of tactics as a whole in the Navy.”

“Developing Technical and Tactical Skill for Warfighters,” by Ed Kaufmann

“If one does not know how a weapon system or a sensor functions technically, then they may not be able to employ it tactically. Once a warfighter has a grasp of how the underlying technology works, they can use that technical know-how to craft tactical solutions for the threat environment they are operating within.”

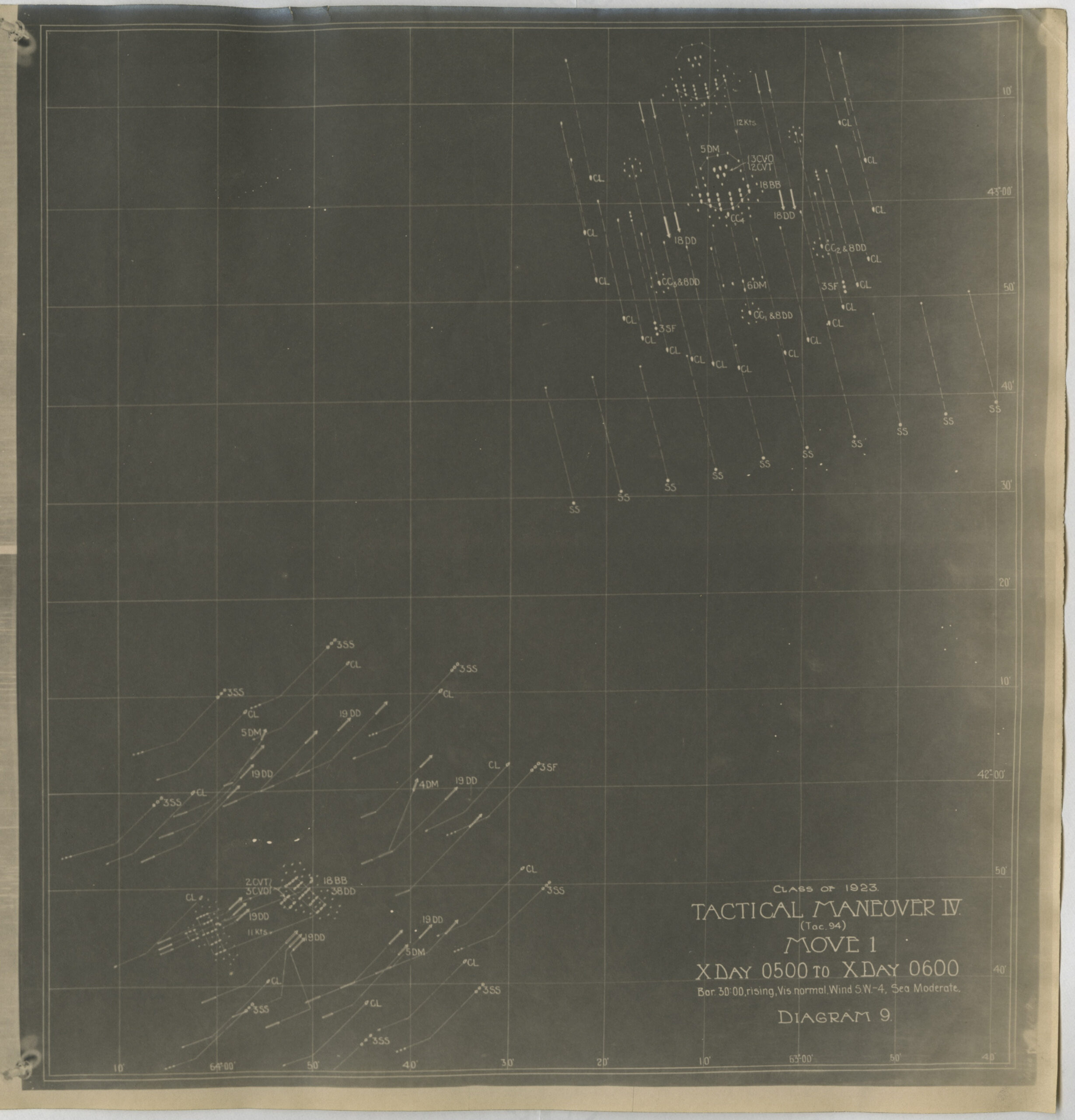

“Make Wargaming Central to Naval War College Education Once Again,” by Robert C. Rubel

“The Navy badly needs for the Naval War College command and staff course to become a year-long classified wargame-centric warfighting course. In such a course students would gain a fleet-level perspective on tactics and be able to link them to operational art and strategy.”

“Invest in Tactical Shiphandling for Crisis and Combat,” by Chris Rielage and Spike Dearing

“As navies invest in more modern and detailed bridge simulators to train Rules of the Road, they should also invest resources to train junior officers on tactical shiphandling. We operate warships, not merchant ships; our measure of effectiveness is not timely deliveries or fuel efficiency, but how effectively we deter or win wars at sea. Our introductory shiphandling courses should reflect that focus.”

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content and Community Manager of the Flotilla. Contact him at Content@cimsec.org.

Featured Image: OROTE POINT, Guam (Oct. 5, 2022) The Los Angeles-class fast-attack submarine USS Springfield (SSN 761) departs Apra Harbor, Guam. (U.S. Navy photo by Lt. Eric Uhden)