Written by Matthew Hipple for Movie Re-Fights Week

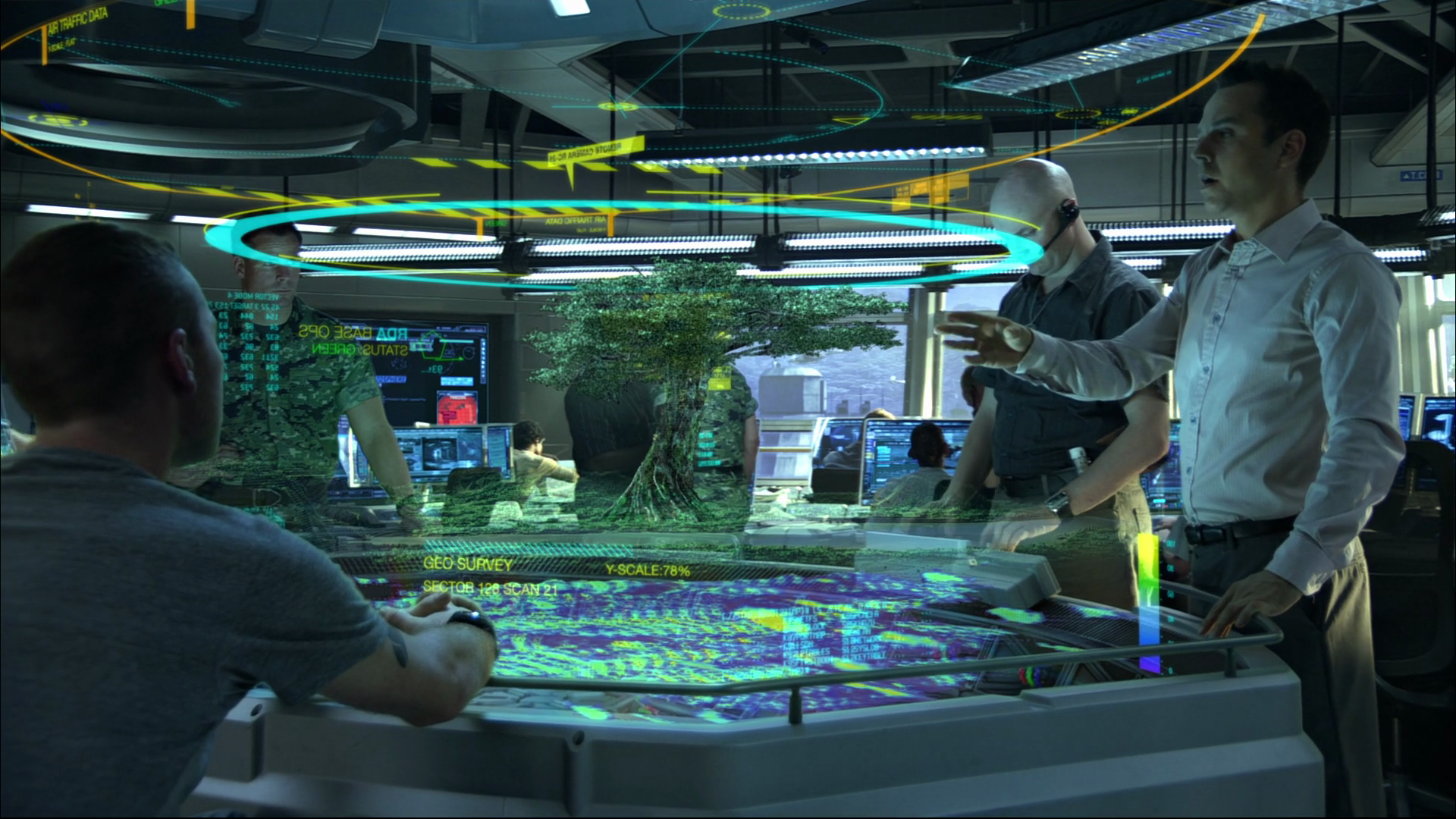

The blockbuster Avatar is not only remarkable for its stunning visuals and brow-beating politics, but for the colossal incompetence of the corporate and military leadership of the Resource Development Administration (RDA).

Sure, humanity may be counting on you for their survival. Sure, you have arrived on an alien planet armed with the ability to transmit your consciousness into proxy flesh suits hewn together with the most advanced science. But hey, why not just “YOLO” it and see what happens? What could go wrong? It’s not like you’re 4.5 light years from earth with limited resources!

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

Tactical Failure: If It Looks Smart and Doesn’t Work – It’s Stupid

Having thoroughly pissed off the blue bees nest on Pandora, RDA command is ordering you to destroy a tiny, purple-glowing “Tree of Souls.” The critical node in a vast planet-wide biological neural net, it is located in the middle of an area of heavy radar interference and the aerial equivalent of deadly shoal water.

RDA commanders probably read the old classic “Starship Troopers” and had heard of Star Craft’s “Zerg” and Halo’s “Flood” from the History Channel. Biological hive minds always end in billions of dead terrans. The mission was probably too important not to staff to death.

What would be more perfect than assigning a massive, vulnerable transport ship carrying a comically lashed-together bomb of mining ordnance through this rock mine-field? Granted, the target is only the size of a Denny’s… OH! Let’s add a ground assault through dense jungle with little to no air support. Never pass up an excuse to party “Ellen Ripley” style in an exo-suit. The plan looked awesome on power point, as one can see from the many unnecessary parts: a militarized space barge and a ground assault. The words “decisive,” “domain,” and “disruptive” probably appeared multiple times.

However, RDA had JUST blown up the Home Tree – a facility the size of a small city – using nothing but a token force of deadly and agile VTOL gunships. Not only was Operation Soul Tree against a far smaller and more fragile target – but it would be in a physically and electronically denied environment. Why suddenly trade mobile lethality for for static defense on a flying dump truck? Why risk losing your entire ground force in a superfluous assault through dense jungle? Seriously, how could this NOT go wrong?

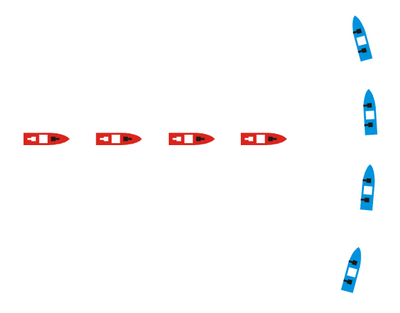

Now, had the RDA forces learned the lesson of their own experience – they would have executed a multi-axis raid on the “Soul Tree” using a primary assault by gunships and a feint by a faux “bomber.” The ground assault would have been completely scrubbed.

Maintaining a “feint” – preferably using gunships and a transport on rudimentary auto-pilot – would draw enemy forces away from the actual angle of attack. The windows of the aircraft used for the feint would have to be blacked out. Recon for Airborne Pandoran forces would quickly discover that the cockpits were empty, and realize the bomber is a feint.

Detaching the primary aerial assault force from the bomber would have allowed pilots speed and flexibility denied to them in the original plan to guard a militarized transport. With Pandoran forces distracted by the potential bombardment by the transport ship, the main assault force would move through the floating boulders at top speed, devastating the Soul Tree with their ordnance before quickly retreating back to base.

With the ground component completely scrubbed, the RDA would retain a significant force to continue defense of their facilities. While these bases are heavily defended already, these are static defenses that require augmentation from mobile components. It would be wise to keep some of the aerial component in reserve as well, in the off chance that Operation Soul Tree failed and human forces would have to hold out until military re-supply from Earth.

Of course, unlike in Operation Guard the Slow and Useless Target, we get to win this time.

Strategic Failure: That Escalated Quickly

But let’s take a step back here – why did the RDA get to the point where it believed it had to commit all its forces to a winner-take-all assault on this Soul Tree network node? Oh, that’s right, they chose to burn down some blue people’s entire capital city.

Granted, the tree is sitting on top of an unobtanium stockpile critical to humanity’s survival… but this is the same human civilization that is capable of creating avatar meat-puppets that can be operated remotely to any location anywhere on this alien planet. Certainly, we can learn the ancient art of lateral drilling?

The vast mining infrastructure operated by the RDA, and the automated technology available to it, would allow humanity some options OTHER than blowing a native city into oblivion to access the resources. It’s the future, surely there are automated mining units that aren’t the size of office buildings, or tunnel-boring machines that could serve this mission.

And let’s be real here – the outfit sent to collect all these resources is the “Resource Development Administration.” Mining should be their specialty.

Force Planning: Phoning it in

The mining technology angle leads us to a more general problem with the technology employed by the RDA. Considering the military and commercial operational needs, the capabilities developed from the technology available seem oddly under developed.

The lack of orbital strike capabilities is notable. From cracking open a large hole for mining to cracking open a target – the RDA would have found great use for an orbital weapon of some sort. It’s not like the mission’s importance to earth didn’t warrant the resources. They certainly had the technology for it. You could destroy ANY tree you really felt necessary – and you wouldn’t have to risk any military forces. Hell, the Pandorans wouldn’t even know it was you. They don’t know how satellites work.

More concerning is the lack of a real military application of the avatar technology the movie is named after. Sure, the modified blue people are a nice touch. Hearts and minds is always the better path then a tough military campaign in someone else’s backyard.

However, why settle for tall skinny blue people? Why not create a legion of 10 foot tall super-Cena ? You could add extra arms, camouflage skin, or even millions of tiny spider-like hairs for extra grip! Perhaps lower cost methods could be employed to save human personnel and maximize combat effectiveness, like making the combat exo-suits neural net operated. Perhaps remote neural control could operate the gunships… or even gunship swarms controlled by a single consciousness. In the movie Surrogates, the DoD was fighting wars with legions of brain-controlled robots… and they weren’t even advanced enough to land a mining operation in another solar system.

Hell, if the RDA had the ability to hack into the neurological network of a surrogate body remotely – why wasn’t anyone trying to tap into this planetary neural net? Imagine the processing capacity of a planet-sized biological computer, or the influence one could have on inter-tribal planetary politics with neural-net access. At the very least, the intelligence gathering potential would be invaluable for a force operating in a potential adversary’s backyard.

Conclusion: Insanity or Laziness

Humanity is in a tight spot – an energy crisis along with dwindling terrain resources mean that unobtanium is humanity’s only way out. Unfortunately, the RDA decision makers on Pandora has decided to phone it in.

Perhaps it’s the cabin fever spending so much time away from civilization. Perhaps it’s the simplicity of mission requirements that involve fighting either animal opponents or blue people armed with sticks. Maybe it’s even the lack of good reading material. Whatever the case, those who were clearly once capable corporate, technical, and military leaders had long ago started slacking off – thinking down predictable or silly stovepipes in their execution of the Pandora mission. It makes a good case for regular leadership rotation. It pays to ensure one’s leadership does not become stale… or even lose their minds from isolation.

Whoever humanity sends to re-take Pandora – and capture the traitor, Jake Sully – will be a bit more on the ball.

Matthew Hipple is the President of CIMSEC and host of our Sea Control and Real Time Strategy podcasts. He is also an active duty Surface Warfare Officer, whose opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the Resource Development Administration.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]