By Greg Smith

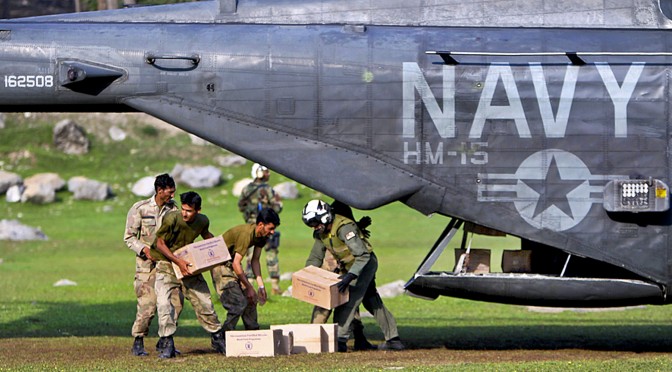

When disaster strikes near the sea, U.S. naval forces are often the first available to execute humanitarian assistance and disaster response (HA/DR) missions. With due regard to the suffering, destruction and loss caused by these disasters, it is possible to note that in many ways these tragedies become opportunities for U.S. naval forces to prepare leaders for combat operations. HA/DR involves a greater sense of urgency and higher stakes than scheduled exercises and training. Especially for the junior officers who participate, HA/DR operations enhance understandings of joint, combined, and interagency coordination and provide an opportunity to develop judgment through prudent risk-taking.

HA/DR operations entail unique, unscripted collaboration with joint and interagency partners. With unity of effort and time as the common enemy, military and civilian organizations cut through red tape and temporarily set parochial interests aside. For leaders at every level, the result is a fundamental and significantly-improved understanding of the capabilities of the “others” with whom they have worked, operated, planned, and communicated during the HA/DR operation.

Anecdotally, the author observed this benefit of HA/DR experience during instruction in Joint Military Operations at the U.S. College of Naval Command and Staff in 2007. Most of the officers in the seminar had served in support of Operations Enduring and Iraqi Freedom in some capacity, and two army officers — a Green Beret and a Special Operations Aviation Regiment pilot — had seen significant combat. For the most part, the army officers outperformed the rest of the seminar in knowledge of joint and service doctrine. However, in understanding joint and interagency capabilities, coordination challenges, and command and control requirements, an E-2C Hawkeye pilot, with extensive experience supporting Hurricane Katrina HA/DR efforts, far surpassed even the army combat veterans. This was not a poor reflection on those army officers (or the rest of the seminar); rather it illustrated the training value of HA/DR missions. The lessons learned and shared during the seminar may significantly enhance the ability of officers to command, coordinate, plan and execute future joint, combined, and interagency operations.

HA/DR also provides an opportunity for junior officers to take prudent risks, pushing themselves and their equipment further than they might otherwise do in peacetime. Making time-critical decisions when lives are on the line develops sound judgment far better than simulations or scripted training scenarios. During training, the most conservative approach is often the most prudent, potentially reinforcing a risk aversion that might not serve officers well in combat. On January 12th 2010, the day a devastating earthquake struck Haiti, a U.S. Navy P-3C Orion waited on deck in El Salvador in a two-hour ready-alert posture in support of counter-drug operations. When tasked to provide reconnaissance over Haiti, the crew expedited departure and was airborne in less than 90 minutes. Within four hours of the earthquake, the Orion was recording critical imagery of Haiti in support of the HA/DR effort that would be named Operation Unified Response. With minimal guidance, the crew was required to make countless time-critical decisions that illustrate the value of HA/DR to the development of sound judgment in naval officers.

Knowing that they would be the only aircraft over Haiti for some time, the P-3 crew began to ascertain the best way to remain on station for as long as possible. Several prudent risk calculations followed. First, the plane would land in Jacksonville, Florida, which was closer to Haiti than El Salvador. Jacksonville also had the technical ability to process the collected video and expedite that intelligence to those directing the response. Second, they would deliberately shut down two engines in flight to minimize fuel consumption.[1] Landing after thirteen hours in flight, the crew relied on the existing support organizations in Jacksonville to deliver the collected imagery, perform daily maintenance on the aircraft and make billeting arrangements. This enabled the crew to take a third prudent risk and execute a second mission with minimal turn-around time. In the forty hours following the earthquake, the crew safely collected more than twenty hours of full motion video and hundreds of images of Haiti’s bridges, roads, ports, and airfields. The junior officers who led the crew balanced guidance found in Navy instructions with the urgency of the mission, taking prudent risks to gather intelligence for planners of HA/DR operations and to assist the earthquake victims. The judgment and leadership skills developed in this effort will be invaluable during combat operations.

Of course, there are important differences between HA/DR and combat operations. The unclassified nature of HA/DR facilitates coordination. The use of any and first-available communication methods (email, mobile phone, unsecured radios) greatly enhances collaboration with host nations, civilian government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and forces afloat or ashore. In addition, access to airfields and ports as well as entry and overflight requirements are expedited, waived or not applicable for forces rendering assistance. During combat operations, the Department of Defense and State Department work tirelessly to enable access for supporting units and staffs in the theater of operations. Maintaining supply routes through Pakistan and access to Manas Air Base in Kyrgyzstan to support combat operations in Afghanistan, for example, demanded constant effort by staffs, planners, and senior leaders, including the Secretary of Defense and Secretary of State. Coordination with partner nations and the U.S. interagency is required during HA/DR, but the willingness to waive access restrictions for military units during HA/DR is often much greater than for combat operations.

These significant differences between HA/DR and combat operations give cause to reevaluate the DoD’s classification policies and methods for ensuring access. Unclassified communications facilitate coordination with interagency, non-governmental and foreign partners. If partnering is critical to the success of future combat operations, the Department of Defense should consider modifying classification or clearance policies to facilitate coordination during combat in some cases. When speed is more important than secrecy or surprise, existing U.S. classification standards could be a hindrance to success. Similarly, the ability to cut through red tape, in both U.S. and partner-nation bureaucracies, could facilitate access during HA/DR missions and benefit future combat operations. Absent the urgency of HA/DR, relationships are required to enable this type of expediency. Developing and maintaining interagency and partner nation relationships that enable access should be a priority for naval forces during peace time.

HA/DR requires naval forces to collaborate, innovate, and take prudent risks to accomplish the mission. These operations provide exposure to joint and interagency operations and offer opportunities for junior officers to make decisions under pressure, facilitating the development of skills that can be valuable in combat. Lessons from HA/DR operations in interacting with interagency and nongovernmental partners abroad should lead U.S. naval forces to rethink classification policies and access strategies. Naval forces should continue to respond to natural disasters to render assistance and save lives. As we seek increasingly adaptive, flexible and agile forces, these missions can prepare naval forces, especially junior officers, for future combat operations.

Commander Greg Smith, USN, is a P-3C naval flight officer and the former commanding officer of VP-26. He is currently serving as a Federal Executive Fellow at the Johns Hopkins University – Applied Physics Lab (APL). The views expressed are his own and do not represent the views of the U.S. Navy or APL.

[1] The four-engine P-3C Orion can increase its endurance at certain weights and airspeeds by loitering (i.e. deliberately shutting down) an engine in flight. During long missions, three-engine flight has been common throughout the 60-year history of the Orion. Loitering two engines can further increase endurance, but it is rarely prudent to do so.