This piece was originally published by the National Defense University Press, and is republished with permission. Read it in its original form here.

By Admiral Jonathan Greenert

Looking ahead to the Department of Defense’s (DOD’s) fiscal prospects and security challenges in the second half of this decade and beyond, the Services and their partners will have to find ever more ingenious ways to come together. It is time for us to think and act in a more ecumenical way as we build programs and capabilities. We should build stronger ties, streamline intelligently, innovate, and wisely use funds at our disposal. We need a broader conversation about how to capitalize on each Service’s strengths and “domain knowledge” to better integrate capabilities. Moving in this direction is not only about savings or cost avoidance; it is about better warfighting.

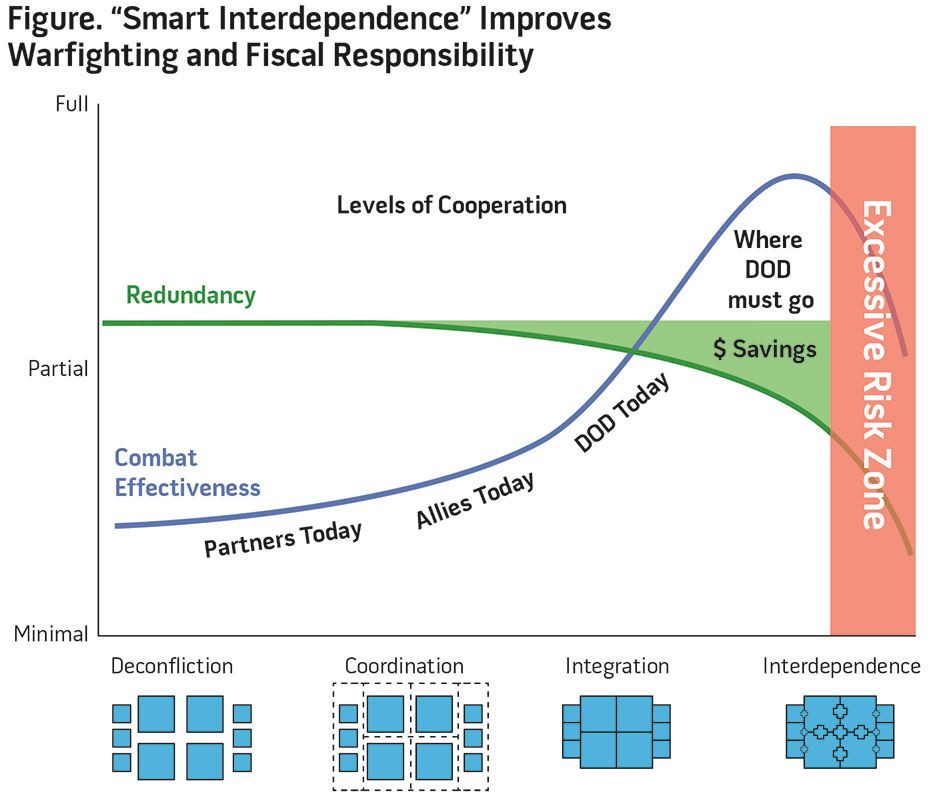

The DOD historical track record shows episodic levels of joint deconfliction, coordination, and integration. Wars and contingencies bring us together. Peacetime and budget pressures seem to compel the Services to drift apart, and more dramatic fiscal changes can lead to retrenchment. While Service rivalries are somewhat natural, and a reflection of esprit de corps, they are counterproductive when they interfere with combat performance, reduce capability for operational commanders, or produce unaffordable options for the Nation. Rather than expending our finite energy on rehashing roles and missions, or committing fratricide as resources become constrained, we should find creative ways to build and strengthen our connections. We can either come together more to preserve our military preeminence—as a smaller but more effective fighting force, if necessary—or face potential hollowing in our respective Services by pursuing duplicative endeavors.

Unexplored potential exists in pursuing greater joint force interdependence, that is, a deliberate and selective reliance and trust of each Service on the capabilities of the others to maximize its own effectiveness. It is a mutual activity deeper than simple “interoperability” or “integration,” which essentially means pooling resources for combined action. Interdependence implies a stronger network of organizational ties, better pairing of capabilities at the system component level, willingness to draw upon shared capabilities, and continuous information- sharing and coordination. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Martin Dempsey notes, “The strength of our military is in the synergy and interdependence of the Joint Force.” Many capstone documents emphasize greater interdependency between the Services’ structures and concepts including the Chairman’s Strategic Direction to the Joint Force, which calls for “combining capabilities in innovative ways.”

These concepts ring true for the maritime Services. The Navy–Marine Corps team has operated interdependently for over two centuries. Symbiotic since their inceptions, Marines engaged in ship-to-ship fighting, enforced shipboard discipline, and augmented beach landings as early as the Battle of Nassau in 1776. This relationship has evolved and matured through the ages as we integrated Marine Corps aviation squadrons into carrier air wings in the 1970s, developed amphibious task force and landing force doctrines, and executed mission-tailored Navy–Marine Corps packages on global fleet stations. Land wars over the last decade have caused some of the cohesion to atrophy, but as the Marines shift back to an expeditionary, sea-based crisis response force, we are committed to revitalizing our skills as America’s mobile, forward-engaged “away team” and “first responders.” Building and maintaining synergy is not easy; in fact, it takes hard work and exceptional trust, but the Navy and Marine Corps team has made it work for generations, between themselves and with other global maritime partners.

The Services writ large are not unfamiliar with the notion of cross-domain synergy. Notable examples of historical interdependence include the B-25 Doolittle Raid on Tokyo from the USS Hornet in 1942 and the Army’s longest ever helicopter assault at the start of Operation Enduring Freedom from the USS Kitty Hawk. The Navy has leaned heavily on Air Force tankers for years, and B-52s can contribute to maritime strikes by firing harpoons and seeding maritime mines. Likewise, other Services have relied on Navy/Marine Corps EA-6B aircraft to supply airborne electronic warfare capabilities to the joint force since the 1990s—paving the way for stealth assets or “burning” routes to counter improvised explosive devices. Examples of where the Navy and Army have closely interfaced include Navy sealift and prepositioning of Army materiel overseas, ballistic missile defense, the Army’s use of Navy-developed close-in weapons systems to defend Iraq and Afghanistan forward operating bases, and the use of Army rotary- wing assets from afloat bases. Special operations forces (SOF) come closest to perfecting operational interdependence with tight, deeply embedded interconnections at all levels among capability providers from all Services.

Opportunities exist to build on this foundation and make these examples the rule rather than the exception. We must move from transitory periods of integration to a state of smart interdependence in select warfighting areas and on Title 10 decisions where natural overlaps occur, where streamlining may be appropriate and risk is managed. From my perspective, advancing joint force interdependence translates to:

- avoiding overspending on similar programs in each Service

- selecting the right capabilities and systems to be “born joint”

- better connecting existing tactics, techniques, procedures, concepts, and plans

- institutionalizing cross-talk on Service research and development, requirements, and programs

- expanding operational cooperation and more effective joint training and exercises.

The Air-Sea Battle (ASB) concept, and the capabilities that underpin it, represent one example of an opportunity to become more interdependent. While good progress has been made on developing the means, techniques, and tactics to enable joint operational access, we have much unfinished business and must be ready to make harder tradeoff decisions. One of the principles of ASB is that the integration of joint forces— across Service, component, and domain lines—begins with force development rather than only after new systems are fielded. We have learned that loosely coupled force design planning and programming results in costly fixes. In the pursuit of sophisticated capability we traded off interoperability and are now doing everything we can to restore it, such as developing solutions for fifth-generation fighters to relay data to fourth-generation ones. ASB has become a forcing function to promote joint warfighting solutions earlier in the development stage. For example, the Navy and Army are avoiding unaffordable duplicative efforts by teaming on the promising capabilities of the electromagnetic railgun, a game-changer in defeating cruise and ballistic missiles afloat and ashore using inexpensive high-velocity projectiles.

Additional areas where interdependence can be further developed include the following.

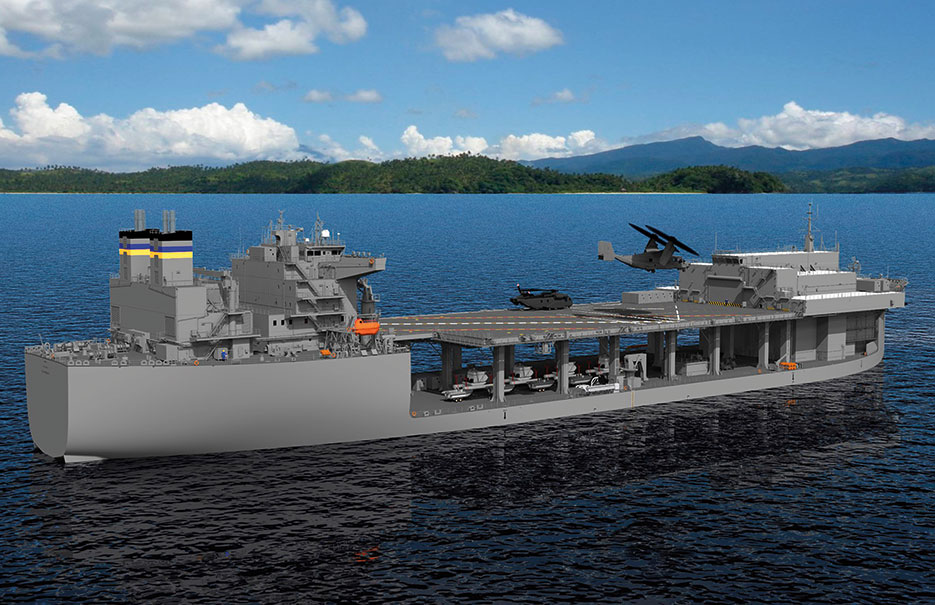

Innovative Employment of Ships. The Navy–Marine Corps team is already developing innovative ways to mix expeditionary capabilities on combatants and auxiliaries, in particular joint high speed vessels, afloat forward staging bases, and mobile landing platforms just starting to join the force. We see opportunities to embark mission-tailored packages with various complements of embarked intelligence, SOF, strike, interagency, and Service capabilities depending on particular mission needs. This concept allows us to take advantage of access provided by the seas to put the right type of force forward— both manned and unmanned—to achieve desired effects. This kind of approach helps us conduct a wider range of operations with allies and partners and improves our ability to conduct persistent distributed operations across all domains to increase sensing, respond more quickly and effectively to crises, and/or confound our adversaries.

Mission-tailored packages for small surface combatants such as the littoral combat ship, and the Navy’s mix of auxiliaries and support ships, would enable them to reduce the demand on large surface combatants such as cruisers and destroyers for maritime security, conventional deterrence, and partnership- building missions. We cannot afford to tie down capital ships in missions that demand only a small fraction of their capabilities, such as contracted airborne intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) services from Aegis destroyers. We are best served tailoring capability to need, interchanging platforms and their payloads suitable to the missions that they are best designed for. At the end of the day, it is about achieving economy of force.

To make these concepts real, the Navy would support an expanded joint effort to demonstrate roll-on, roll-off packages onto ships to create a set of specialized capability options for joint force commanders. Adaptive force packages could range from remote joint intelligence collection and cyber exploit/attack systems, SOF, modularized Army field medical units, humanitarian assistance/ disaster relief supplies and service teams, to ISR detachments—either airborne, surface, or subsurface. Our ships are ideal platforms to carry specialized configurations, including many small, autonomous, and networked systems, regardless of Service pedigree. The ultimate objective is getting them forward and positioned to make a difference when it matters, where it matters.

Tightly Knitted ISR. We should maximize DOD investments in ISR capabilities, especially the workforce and infrastructure that supports processing, exploitation, and dissemination (PED). SOF and the Air Force are heavily invested in ISR infrastructure, the Army is building more reachback, and the Navy is examining its distribution of PED assets between large deck ships, maritime operations centers, and the Office of Naval Intelligence. While every Service has a responsibility to field ISR assets with sufficient “tail” to fully optimize their collection assets, stovepiped Service-specific solutions are likely too expensive. We should tighten our partnerships between ISR nodes, share resources, and maximize existing DOD investments in people, training, software, information systems, links/circuits, communications pipes, and processes. To paraphrase an old adage, “If we cannot hang together in ISR, we shall surely hang separately.”

ISR operations are arguably very “purple” today, but our PED investment strategies and asset management are not. Each Service collects, exploits, and shares strategic, anticipatory, and operational intelligence of interest to all Services. In many cases, it does not matter what insignia or fin flash is painted on the ISR “truck.” Air Force assets collect on maritime targets (for example, the Predator in the Persian Gulf), and Navy assets collect ashore (the P-3 in Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom). Yet each Service still develops its own particular PED solutions. We should avoid any unnecessary new spending where capability already exists, figure out dynamic joint PED allocation schemes similar to platform management protocols, and increase the level of interdependency between our PED nodes. Not only is this approach more affordable, but it also makes for more effective combat support.

We can also be smarter about developing shared sensor payloads and common control systems among our programmers while we find imaginative ways to better work the ISR “tail.” Each Service should be capitalizing on the extraordinary progress made during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom in integrating sensors, software, and analytic tools. We should build off those models, share technology where appropriate, and continue to develop capability in this area among joint stakeholders.

Truly Interoperable Combat and Information Systems. The joint force has a shared interest in ensuring sufficient connectivity to effect information-sharing and command and control in all future contingencies. We cannot afford to develop systems that are not interconnected by design, use different data standards/ formats, come without reliable underlying transport mechanisms, or place burdens on our fielded forces to develop time-consuming workarounds. We still find DOD spending extraordinary time and effort healing itself from legacy decisions that did not fully account for the reality that every platform across the joint community will need to be networked.

Greater discipline and communication between planners, programmers, acquisition professionals, and providers for information systems at all classification levels are required. We must view all new information systems as part of a larger family of systems. As such, we should press hard to ensure convergence between the DOD Joint Information Environment and the Intelligence Community’s Information Technology Enterprise initiatives. Why pay twice for similar capabilities already developed somewhere else in the DOD enterprise? Why would we design a different solution to the same functional challenge only because users live in a different classification domain? Ensuring “best of breed” widgets, cloud data/storage/ utility solutions, advanced analytics, and information security capabilities are shared across the force will require heightened awareness, focused planning, inclusive coordination, and enlightened leadership for years to come.

In the world of information systems, enterprise solutions are fundamentally interdependent solutions. They evolve away from Service or classification domain silos. We are not on this path solely because we want to be thriftier. Rationalizing our acquisition of applications, controlling “versioning” of software services, reducing complexity, and operating more compatible systems will serve to increase the flow of integrated national and tactical data to warfighters. This, in turn, leads to a better picture of unfolding events, improved awareness, and more informed decisionmaking at all levels of war. Enterprise approaches will also reduce cyber attack “surfaces” and enable us to be more secure.

In our eagerness to streamline, connect, and secure our networks and platform IT systems, we have to avoid leaving our allies and partners behind. Almost all operations and conflicts are executed as a coalition; therefore, we must develop globally relevant, automated, multilevel information-sharing tools and update associated policies. This capability is long overdue and key to enabling quid pro quo exchanges. Improved information-sharing must become an extensible interdependency objective between joint forces, agencies, allies, and partners alike. Improving the exchange of information on shared maritime challenges continues to be a constant refrain from our friends and allies. We must continue to meet our obligations and exercise a leadership role in supporting regional maritime information hubs such as Singapore’s Information Fusion Center, initiatives such as Shared Awareness and Deconfliction (SHADE) designed for counterpiracy, and other impromptu coalitions formed to deal with unexpected crises.

Other fields to consider advancing joint force interdependence include cyber and electromagnetic spectrum capabilities, assured command and control (including resilient communications), ballistic missile defense, and directed energy weapons.

To conclude, some may submit that “interdependence” is code for “intolerable sacrifices that will destroy statutory Service capabilities.” I agree that literal and total interdependence could do just that. A “single air force,” for example, is not a viable idea. Moreover, each branch of the military has core capabilities that it is expected to own and operate—goods, capabilities, and services no one else provides. As Chief of Naval Operations, I can rely on no other Service for sea-based strategic deterrence, persistent power projection from forward seabases, antisubmarine warfare, mine countermeasures, covert maritime reconnaissance and strike, amphibious transport, underwater explosive ordnance disposal, diving and salvage, or underwater sensors, vehicles, and quieting. I cannot shed or compromise those responsibilities, nor would I ask other Services to rush headlong into a zone of “interdependence” that entails taking excessive risks.

Joint interdependence offers the opportunity for the force to be more efficient where possible and more effective where necessary. If examined deliberately and coherently, we can move toward smarter interdependence while avoiding choices that create single points of failure, ignore organic needs of each Service, or create fragility in capability or capacity. Redundancies in some areas are essential for the force to be effective and should not be sacrificed in the interest of efficiency. Nor can we homogenize capabilities so far that they become ill suited to the unique domains in which the Services operate.

Over time, we have moved from deconflicting our forces, to coordinating them, to integrating them. Now it is time to take it a step further and interconnect better, to become more interdependent in select areas. As a Service chief, my job is to organize, train, and equip forces and provide combatant commanders maritime capabilities that they can use to protect American security interests. But these capabilities must be increasingly complementary and integral to forces of the other Services. What we build and how we execute operations once our capabilities are fielded must be powerful and symphonic.

Together, with a commitment to greater cross-domain synergy, the Services can strengthen their hands in shaping inevitable force structure and capability tradeoff decisions on the horizon. We should take the initiative to streamline ourselves into a more affordable and potent joint force. I look forward to working to develop ideas that advance smart joint interdependence. This is a strategic imperative for our time. JFQ

Admiral Jonathan Greenert served as the 30th Chief of Naval Operations of the United States Navy from 2011-2015.