By Scott C. Truver

Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Michael M. Gilday has good reason to recall the morning of 18 February 1991. In support of Operation Desert Storm, the Aegis guided-missile cruiser USS Princeton (CG-59) was patrolling off Failaka Island in the northern Persian Gulf, with a young Lieutenant Gilday serving as the tactical action officer (TAO). At 0715 local time, two Italian-made MN103 MANTA multiple-influence bottom mines, each loaded with 325 pounds of TNT/PXBN explosive, fired.1

The first MANTA detonated directly under the warship’s port rudder in shallow water, and the second some 200 yards off the starboard bow, a sympathetic explosion that did no damage. The first, however, injured three crewmembers, cracked the superstructure, buckled the hull at three frames, jammed the port rudder, damaged the starboard propeller shaft, and flooded the Number 3 switchboard room from chill-water pipe cracks that shut down combat systems for 90 minutes—a dead-in-the-water “mission kill” that rendered missiles and guns aft inoperable.

Four hours earlier, the USS Tripoli (LPH-10) had struck an Iraqi LUGM contact mine, ripping a 25’x25’ hole in her starboard hull. Ironically, Tripoli embarked aircraft of the Navy’s MH-53E airborne mine-countermeasures (AMCM) MH-14 helicopter squadron. Because the damage was limited only to hull voids, skillful ship-handing and ballasting kept Tripoli’s AMCM helos operating for another six days.

These mine events underscored the lessons that any ship can be a mine-sweeper, once, and a single mine cannot only ruin a skipper’s day but can also frustrate overall strategy, planning, and operations. Almost immediately following the Princeton and Tripoli mine strikes, the multinational coalition shelved plans to liberate Kuwait from the sea.

In 2021 the threat is worldwide: some 30 countries manufacture mines for their navies, and about 20 of these will sell to anyone with cash in hand.

Potential U.S. adversaries—from China and Russia to violent extremists—take advantage of the asymmetric value of mines, some quite sophisticated and lethal and others unsophisticated but still quite lethal. The global threat includes: Russia, anywhere from 125,000 to a million mines; upwards of 80,000 are in Chinese inventories; as many as 10,000 enhance North Korea’s navy; Iran has about 6,000; and unknown numbers are in terrorist hands. In June 2021, for example, Houthi rebels warned about “some hundreds of sea mines” laid in Red Sea and Arabian Sea ports and waterways.2

In comparison, the U.S. Navy has stockpiled fewer than 10,000 dedicated mines—including a “handful” of Mk-67 Submarine-Launched Mobile Mines (SLMMs) that can be deployed only on the remaining Improved Los Angeles-class (I688) attack submarine, and “Quickstrike” (QS) mine-conversion kits for general-purpose bombs.3

While there looks to be a faint light at the end of the naval mining tunnel, Big Navy has not embraced incorporating offensive and defensive mine capabilities into strategic thinking, other than half-hearted mollifying. For example, the 2020 tri-service maritime strategy mentions mine warfare only twice, first in the context of “Alliances and partnerships are true force multipliers in times of crisis. Partner and ally deployments . . . also provide specialty capabilities, such as mine warfare and antisubmarine warfare.”4 “Mine warfare” in this instance is code for “mine countermeasures.”

The 2020 strategy also promises to “expand mine warfare capabilities” as components of undersea warfare, clearly a reference to mines and mining. But hope can be fickle. The last time the Navy put a new-design dedicated mine into service was 1983, and today’s U.S. in-service mines and mining capabilities are obsolescent, with questionable value in crises and conflicts.

Comprehensive mine warfare visions and strategies have been sporadic for at least ten years, and dynamics internal and external to the Navy’s mine warfare community have kept MIW in its place. Visions and strategies never see the light of day; the Navy continues to relegate mine warfare—mines, mining, and mine countermeasures—to a strategic, operational, and budgetary backwater.5

While hope is not a strategy, tomorrow’s naval mines/mining technologies, systems, concepts of operations, and operational planning tools could energize these weapons that wait by what they might bring to the fight—and how they will get there. Moreover, these initiatives and programs could shape our understanding of what constitutes a mine. That said, rhetoric needs to be channeled into reality.

For example, the Navy is upgrading the Mk-65 2,300-pound shallow-water dedicated thin-wall bottom mines and the Mk-62 500-pound and Mk-63 1,000-pound Quickstrike bomb-conversion multi-influence bottom mines with the state-of-the-art Mk-71 target-detection-device firing mechanism.6 It senses magnetic, acoustic, seismic, and pressure signatures and can be programmed with target-processing and counter-countermeasures algorithms. The Navy’s miners now can optimize mining performance against many different targets. But it took nearly 20 years to transition the Mk-71 from an engineering concept to fleet introduction.

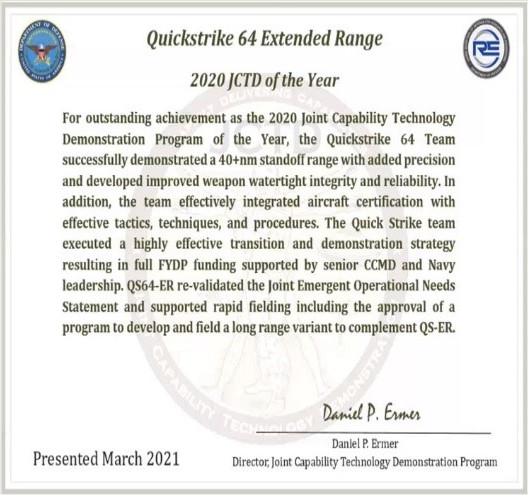

A developmental 2,000-pound version of the Joint Direct-Attack Munition/Quickstrike Extended-Range (JDAM/QS-ER) earned the Office of the Secretary of Defense 2020 Joint Capability Technology Demonstration program-of-the-year award. Program officials note they are also developing a propulsion pack for a power-glide version of the ER (QS-P), perhaps leading to very extended-standoffs and highly precise/accurate “cruise-missile mines.” Sufficient and stable funding for this capability, however, looks to be frustrated, at best. Indeed, it could see funding zeroed in fiscal year 22.7

https://gfycat.com/mammothleadinghyracotherium

A Quickstrike-ER (QS-ER) naval mine drops toward the Pacific Ocean during an operational demonstration on 30 May 2019. (Video by Petty Officer 1st Class Robin Peak, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command)

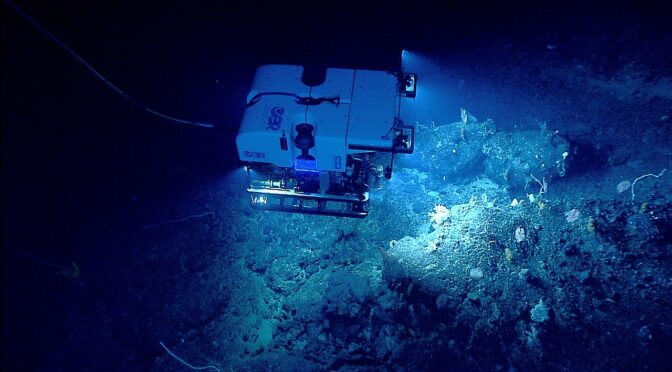

In addition to aerial mining options, efforts are ongoing to expand near-term undersea-delivered mining capabilities. The Navy is repurposing excess Mk 67 SLMM warheads to develop Clandestine Delivered Mines (CDMs) delivered by Orca unmanned vehicles.

Another concept envisions using networked “encapsulated effectors” similar to the out-of-service moored Cold War Mk 60 CAPTOR (enCAPsulated TORpedo) to carry out numerous vital seabed warfare activities. The new “Hammerhead” device could also support Marine Corps expeditionary advance base operations antisubmarine warfare efforts, as well as other offensive and defensive mining functions.8 Indeed, future U.S. mines could be important elements of expeditionary distributed lethality, contributing to forward-area operational objectives and overall warfighting effects.

The U.S. Navy’s existing and new mine capabilities could provide an additional layer of defense around strategic assets like naval bases, ports, or even surrounding temporary outposts or forces deployed on small islands like those that dot the Mediterranean or the Pacific. Mines have long been a major component of denying access to certain areas or deterring amphibious landings, for instance. Most importantly, the use of standoff mines or those covertly emplaced by a submarine could prevent adversaries from projecting their own forces, including even leaving their harbors, during a time of war.9

So, CNO: Remember your 18 February 1991 introduction to naval mine warfare. Thirty years on, the Navy’s mines and mining objective must make America’s adversaries worry about the threat of mines and seabed warfare systems more than their weapons concern the United States and its allies and partners.

Finding the scarce resources to fund these programs will be an increasingly daunting proposition, however. The reality is since the 1991 Persian Gulf mine debacles USN mine warfare has received each year and average of about 0.75% of Navy total obligational authority. And most of that focused on remedial mine countermeasures.

Damn the “torpedoes” indeed!

Dr. Truver is Manager, Naval and Maritime Program, Gryphon Technologies LC (struver@GryphonLC.com). He has supported U.S. mine warfare strategies, policies, programs, and operations since 1979, including the Navy’s first post-Cold War Mine Warfare Strategic Plan (OP03/372, January 1992). And he is the co-author of Weapons that Wait: Mine Warfare in the U.S. Navy (Naval Institute Press 1991 second edition).

An earlier version of this manuscript was published in the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings/Naval Review, May 2021, Vol.147/5/1,419, “Need to Know” commentary: https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2021/may/not-your-grandfathers-weapons-wait. It is used by permission of Proceedings.

End Notes

1. Scott C. Truver, “Lessons from the Princeton Incident,” International Defense Review, 7/1991. Also, MANTA Anti landing Shallow Water Mine, RWM Italia SPA, Rheinmetall Defence, www.rwm-italia.com, 2012.

2. Arie Egozi, “Houthis Lay Sea Mines in Red Sea; Coalition Boasts Few Minesweepers, Breaking Defense, 14 June 2021, https://breakingdefense.com/2021/06/houthis-lay-sea-mines-in-red-sea-coalition-boasts-few-minesweepers/

3. Brett Tingley, “Navy Offers Gimps of its Submarine-Launched Capabilities in the Mediterranean,” The WarZone, 28 June 2021, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/41309/navy-offers-glimpse-of-its-submarine-launched-mine-capabilities-in-the-mediterranean

4. Advantage at Sea: Prevailing with Integrated All-domain Naval Power, December 2020, pp. 13 and 22.

5. In June 2009 the Program Executive Office for Littoral and Mine Warfare (PEO LMW) and the Expeditionary Warfare Directorate (N85) published what came to be regarded as the “MIW Primer’: 21st Century U.S. Navy Mine Warfare: Ensuring Global Access and Commerce. The 3,500 copies were soon depleted, but it remains on the Internet: https://www.scribd.com/document/329688556/21st-Century-u-s-Navy-Mine-Warfare

6. Captain Hans Lynch USN/N952) and Scott Truver, “Toward a 21st-Century US Navy Mining Force,” Defense One, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2018/08/toward-21st-century-us-navy-mining-force/150709/

7. Tyler Rogoway, “B-52 Tested 2,000 Quickstrike-ER Winged Standoff Naval Mines during Valiant Shield,” The WarZone, 20 September 2018, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/23705/b-52-tested-2000lb-quickstrike-er-winged-standoff-naval-mines-during-valiant-shield

8. “Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations,” Headquarters United States Marine Corps, 8 February 2021

9. Tyler Rogoway, op.cit.

Feature Image: PACIFIC OCEAN (March 16, 2009) Aviation Ordnancemen inspect MK-62 mines on the flight deck of the aircraft carrier USS John C. Stennis (CVN 74) in preparation for loading onto aircraft as part of Exercise Foal Eagle 2009. Foal Eagle is a defense-oriented annual training exercise with the Republic of Korea demonstrating U.S. commitment to regional peace and stability. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Ronda Spaulding/Released)