By Tobias Oder

Introduction

Over the last few years, the Russian Federation pursued an increasingly assertive foreign policy in Eastern Europe. Geopolitical infringements on Crimea and Eastern Ukraine are coupled with hybrid warfare and aggressive rhetoric. The buildup and modernization of the Russian armed forces underpins this repositioning and Russia has taken major steps in increasing its conventional and nuclear capabilities.

The significant rearmament of its Western exclave Kaliningrad requires special attention.1 The recent buildup of Russian A2/AD forces in Kaliningrad, coupled with increasingly assertive behavior in the Baltic Sea, poses a serious challenge for European naval policy. Should Russia make active use of its sea denial forces, it could potentially shut down access to the Baltic Sea and cut maritime supply lines to the Baltic states. The full range of Russia’s A2/AD capabilities in Kaliningrad comprises a wide array of different weapon systems, ranging from SA-21 Growler surface-to-air missiles2 to a squadron of Su-27 Flanker fighters and another squadron of Su-24 Fencer attack aircrafts3 that can be scrambled at a moment’s notice to contest Baltic Sea access.4 German naval capabilities to counter the SS-C-5 Stooge anti-ship missile system,5 Russia’s mining of sea lanes, and its attack submarines are of particular interest in retaining Baltic sea control.

Russian A2/AD Systems

The K300 Bastion-P system includes in its optional equipment a Monolit-B self-propelled coastal radar targeting system.6 This radar system is capable of, according to its manufacturer, “searching, detection, tracking and classification of sea-surface targets by active radar; over-the-horizon detection, classification, and determination of the coordinates of radiating radars, using the means of passive radar detection and ranging.”7The manufacturer further states that sea-surface detection with active radar ranges up to 250 kilometers under perfect conditions, while the range of sea surface detection with passive detection reaches 450 kilometers.8

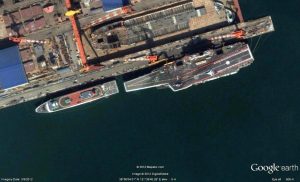

With regard to its undersea warfare capabilities, the Russian Baltic Fleet currently only operates two Kilo-class submarines. Of these diesel-powered submarines, only one is currently operational with the other unavailable due to repairs for the foreseeable future.9 However, the entire Russian Navy’s submarine fleet is currently undergoing rapid modernization and the Baltic Fleet will receive reinforcements consisting of additional improved Kilo-class submarines.10 Despite the fact that the Baltic fleet remains relatively small in size, these upgrades amount to “a level of Russian capability that we haven’t seen before” in recent years.11

With its formidable ability to float through waters largely undetected and versatile missile equipment options capable of attacking targets on water and land, the Kilo-class presents a serious threat to naval security in the region.12 In fact, its low noise level has earned it the nickname “The Black Hole.”13

The Baltic Sea is relatively small in size and has only a few navigable passageways that create chokepoints. Therefore, it resembles perfect terrain for the possible use of sea mines.14 While often underestimated, sea mines can have a devastating impact on naval vessels. Affordable in price and hard to detect, they can be an effective area-denial tool if spread out in high quantities.15 Russia still possesses the largest arsenal of naval mines, and according to one observer, Russia has “a good capability to put weapons in the water both overtly and covertly.”16 The versatility of possible launch platforms, ranging from full-sized frigates to fishing boats, makes an assessment of current capabilities in Kaliningrad a difficult endeavor.

A Possible Scenario for Russian A2/AD Operations in the Baltic Sea

Given Russia’s long-term strategic inferiority to western conventional capabilities, a realistic scenario will bear in mind that Russia is not interested in vertical conflict escalation. Instead, it is primarily interested in exploiting its temporary regional power superiority.17 Thus, its endgame will not be to destroy as many enemy vessels as possible, but rather to send a signal to opponents and deter them from navigating their ships east of German territorial waters as long as needed.18 Ultimately, A2/AD capabilities only have to inflict so much damage to make defending the Baltic States appear unattractive or too costly to decision makers, especially if those measures can create the perception of Russian escalation dominance.19

Russia is very inclined to use means that offer plausible deniability, to possibly include sea mines.20 The Baltic Sea is still riddled with sea mines from both World Wars21 and if Russia manages to lay sea mines undetected, it can make the argument that any incidents in the Baltic Sea involving sea mines were simply due to old, leftover mines instead of newly deployed Russian systems.

Should measures to deploy sea mines in the Baltic Sea fail, Russia may consider use of a more overt, multi-layered approach to sea denial. We can expect that a realistic scenario will feature a mixture of above-mentioned approaches that include submarine warfare as well as the use of anti-ship missiles. Russia could also make use of its naval aviation assets and other missile capabilities stationed in Kaliningrad.

Strategic Implications and NATO’s Interests

It is difficult to interpret the deployment of these weapon systems and missiles as anything different than an addition to Russia’s A2/AD capabilities. Russia is actively trying to improve it strategic position to deter possible troops movements on land as well as on the water.22 They mirror Russia’s claims to its sphere of influence in Eastern Europe and serve as an example of Russia’s attempts to exert authority over its periphery, effectively giving Russia the potential to deny access to the Baltic Sea east of Germany.

If Russia increases its A2/AD capabilities in the Baltic Sea, it complicates NATO’s access to the Baltic states during a potential crisis. This is especially startling due to the fact that NATO troops are currently stationed in the Baltics and cutting off maritime supply routes would leave those troops extremely vulnerable. If Russia can effectively cut off NATO’s access to the Baltic states, it increases the “attractiveness to Russia of a fait-accompli.”23 Ben Hodges, then-commanding general of the United States Army in Europe, shared these concerns: “They could make it very difficult for any of us to get up into the Baltic Sea if we needed to in a contingency.”24 In case regional states will be called to fulfill its alliance commitments in the Baltic Sea, Russian submarine blockades, along with mining and missile deployments, will be a major roadblock and possibly threaten safe passage for European vessels.

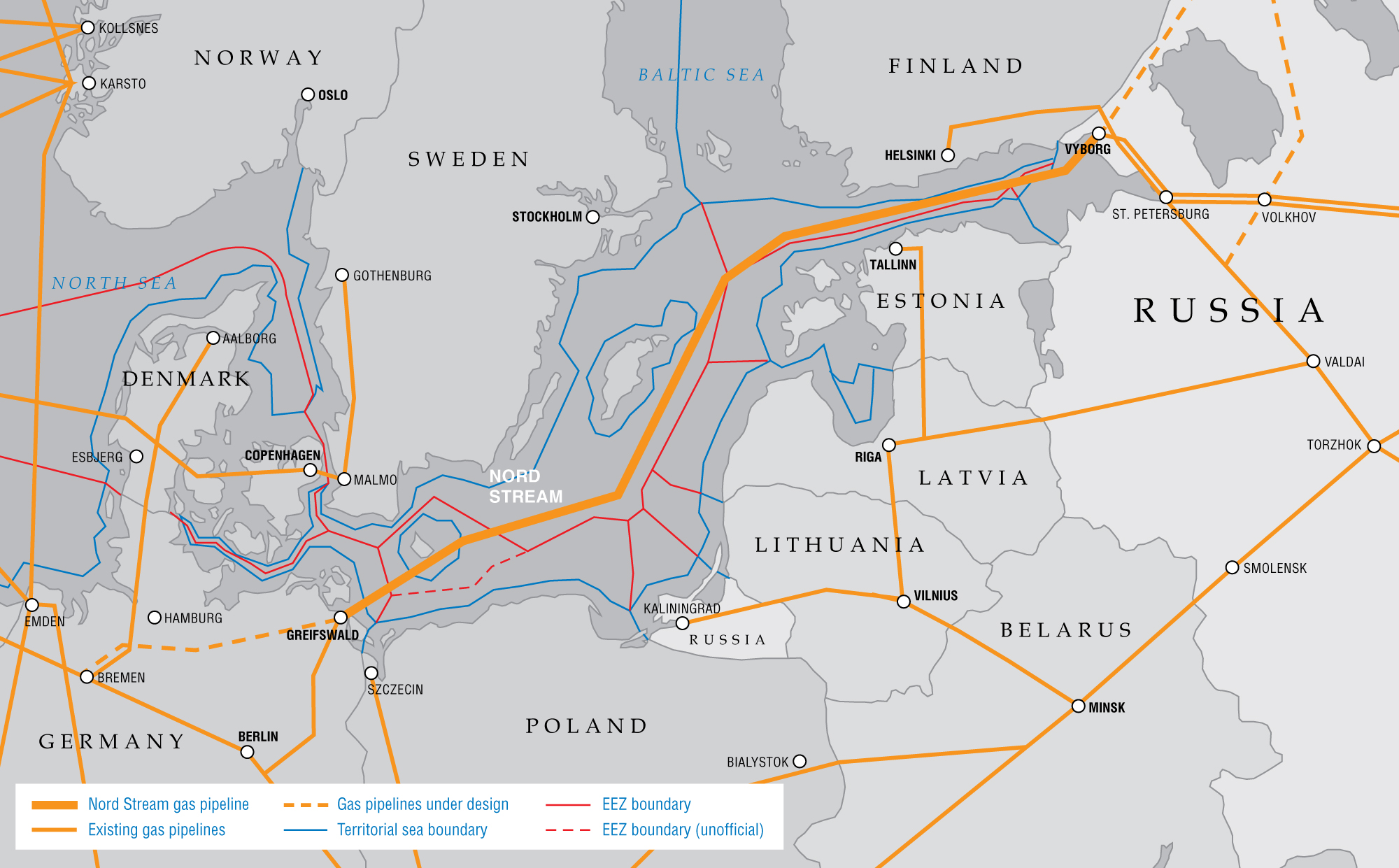

NATO has an immense national interest in maintaining freedom of navigation in the Baltic Sea and ensuring free access. On average, 2,500 ships are navigating the Baltic Sea at any time and its shipping routes are vital to European economic activity.25 In the 2016 German Defence White Paper, this is clearly identified: “Securing maritime supply routes and ensuring freedom of the high seas is of significant importance for an exporting nation like Germany which is highly dependent on unimpeded maritime trade. Disruptions to our supply routes caused by piracy, terrorism and regional conflicts can have negative repercussions on our country’s prosperity.”26 Thus, if Russia impedes freedom of navigation in this area with its A2/AD capabilities, it will significantly damage Germany’s and other European nations’ export potential. However, vulnerabilities are not limited to shipping routes but also include the Nord Stream gas pipeline and undersea cables upon which a large part of European economies depend.27

In sum, Russia’s A2/AD systems, along with updated submarine capabilities and the potentially disastrous effects of disrupted undersea pipelines and communication cables, enhance Russia’s strategic position and makes hybrid warfare a more realistic scenario. This kind of instability would have serious security and economic implications for NATO.

Recommendations

Should the Baltic Sea fall under de facto authority of the Russian Federation or witness conventional or hybrid conflict, then NATO would face dire economic consequences and live with a conflict zone at its doorstep. This is especially concerning given the poor state of Germany’s naval power in particular. The German Navy lacks most capabilities that would qualify it as a medium-sized navy, and its strategy is mostly agnostic of a threat with significant A2/AD capabilities just East of its own territorial waters.28 Since it is in Germany’s vital interest to maintain freedom of navigation in the Baltic Sea and plan for a potential use of Russian A2/AD capabilities, the German Navy should shift its operational focus to the Baltic Sea. Having outlined the means through which Russia can deny access to the Baltic Sea, specific recommended actions can follow.

Effectively countering the effects of anti-ship missiles stationed in Kaliningrad requires two measures. First, it requires the German Navy to equip its ships and submarines with standoff strike capabilities that enable them to engage Russian radars and anti-ship missiles from outside their A2/AD zone.29 In practice, this requires the procurement of conventional long-range land-strike capabilities for the German Navy. To this day, the entire German fleet lacks any form of long-range land-attack weapon for both surface vessels and submarines.30 Second, if the German Navy has to operate within Russia’s A2/AD environment, it should equip its surface ships with more advanced electronic warfare countermeasures that disrupt sensing and enable unit-level deception.

Russia’s submarines are traditionally hard to detect, but they can be countered by Germany’s own class of 212A submarines. Those feature better sonars and are even quieter, giving them an advantage over Russia’s submarines.31 However, in order to fully exploit this advantage, Germany has to do a better job of committing resources to the maintenance of its submarines as all six of its active submarines are currently not operational due to maintenance.32

A large part of the effectiveness of anti-mine operations hinges on preemptive detecting. If Germany and other NATO allies can catch Russia in the act of laying mines, it will actively decrease the possible damage those mines can do to vessels in the future and thus their effect on sea denial.33 It can do so by increasing its sea patrols in the region. These patrols can include minimally armed vessels such as the Ensdorf and Frankenthal classes in order to avoid incidental confrontations and to assume a non-threatening stance toward Russia. If preventive action fails, Germany should be ready to employ a NATO Mine Countermeasure Group in order to clear as many mines as possible and to ensure safe passage of ships.

Conclusion

The buildup of forces on Russia’s Western border is paired with a more aggressive stance by the Russian military. Over the last months, the Baltic Sea became “congested” with Russian military activity, leading to increasingly closer encounters.34 In April 2014, an unarmed Russian Su-24 jet made several low-passes near a U.S. missile destroyer, the USS Donald Cook in the Baltic Sea.35 Later in 2014, a small Russian submarine navigating in Swedish territorial waters spurred a Swedish military buildup along its coast due to “foreign underwater activity.”36 And during July 2017, Russia conducted joint naval exercises with China in the Baltic Sea. By conducting a joint naval drill with China in these waters, the Russian military demonstrated strength and flexed its military muscle in a message specifically directed at NATO.37 These actions by the Russian military all point toward conveying the message that Russia does not want the presence of foreign militaries in Baltic Sea waters and is capable of taking countermeasures to exert its sovereignty in the region.

Tobias Oder is a graduate student in International Affairs at the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University. He focuses on international security, grand strategy, and transatlantic relations

References

[1] “The Baltic Sea and Current German Naval Strategy,” Center for International Maritime Security, last modified July 20, 2016, accessed September 22, 2017, https://cimsec.org/baltic-sea-current-german-navy-strategy/26194.

[2] Also known as S-400 Triumf.

[3] “Chapter Five: Russia and Eurasia,” The Military Balance 117, no. 1 (2017), 183-236.

[4] “Entering the Bear’s Lair: Russia’s A2/AD Bubble in the Baltic Sea,” The National Interest, last modified September 20, 2016, accessed September 24, 2017, http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/entering-the-bears-lair-russias-a2-ad-bubble-the-baltic-sea-17766?page=show.

[5] Also known as K-300P Bastion-P.

[6] “K-300P Bastion-P System Deliveries Begin,” Jane’s, last modified March 5, 2009, accessed November 20, 2017, https://my.ihs.com/Janes?th=janes&callingurl=http%3A%2F%2Fjanes.ihs.com%2FMissilesRockets%2FDisplay%2F1200191.

[7] “Monolit-B,” Rosoboronexport,, accessed November 20, 2017, http://roe.ru/eng/catalog/naval-systems/stationary-electronic-systems/monolit-b/.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Kathleen H. Hicks et al., Undersea Warfare in Northern Europe (Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2016).

[10] Karl Soper, “All Four Russian Fleets to Receive Improved Kilos,” Jane’s Navy International 119, no. 3 (2014).

[11] “Russia Readies Two of its most Advanced Submarines for Launch in 2017,” The Washington Post, last modified December 29, 2016, accessed September 23, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/checkpoint/wp/2016/12/29/russia-readies-two-of-its-most-advanced-submarines-for-launch-in-2017/?utm_term=.2976db8c1710.

[12] “The Kilo-Class Submarine: Why Russia’s Enemies Fear “the Black Hole”, The National Interest, last modified October 23, 2016, accessed November 21, 2017, http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-kilo-class-submarine-why-russias-enemies-fear-the-black-18140.

[13] “Silent Killer: Russian Varshavyanka Project 636.3 Submarine,” Strategic Culture Foundation, last modified July 14, 2016, accessed November 21, 2017, https://www.strategic-culture.org/news/2016/07/14/silent-killer-russian-varshavyanka-project-636-3-submarine.html.

[14] Stephan Frühling and Guillaume Lasconjarias, “NATO, A2/AD and the Kaliningrad Challenge,” Survival 58, no. 2 (April-May, 2016), 95-116.; Alexander Lanoszka and Michael A. Hunzeker, “Confronting the Anti-Access/Area Denial and Precision Strike Challenge in the Baltic Region,” The RUSI Journal 161, no. 5 (October/November, 2016), 12-18.; Hicks et al., Undersea Warfare in Northern Europe.

[15] “Sea Mines: The most Lethal Naval Weapon on the Planet,” The National Interest, last modified September 1, 2016, accessed November 21, 2017, http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/sea-mines-the-most-lethal-naval-weapon-the-planet-17559. In fact, even a small number of sea mines have the capability to disrupt marine traffic due to the perceived risk of a possible lethal encounter (Caitlin Talmadge, “Closing Time: Assessing the Iranian Threat to the Strait of Hormuz,” International Security 33, no. 1 (Summer, 2008), 82-117.).

[16] “Minefields at Sea: From the Tsars to Putin,” Breaking Defense, last modified March 23, 2015, accessed November 21, 2017, https://breakingdefense.com/2015/03/shutting-down-the-sea-russia-china-iran-and-the-hidden-danger-of-sea-mines/.

[17] Frühling and Lasconjarias, NATO, A2/AD and the Kaliningrad Challenge, 95-116, 100.

[18] Lanoszka and Hunzeker, Confronting the Anti-Access/Area Denial and Precision Strike Challenge in the Baltic Region, 12-18 Specifically, commentators outline various scenarios that all share the basic notion that the ultimate goal is to deny NATO forces access to its eastern flank (“Anti-Access/Area Denial Isn’t just for Asia Anymore,” Defense One, last modified April 2, 2015, accessed November 20, 2017, http://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2015/04/anti-accessarea-denial-isnt-just-asia-anymore/109108/).

[19] Andrew F. Krepinevich, Why AirSea Battle? (Washington, D.C.: CSBA, 2010). For a more detailed discussion of potential Russian escalation dominance, see David A. Shlapak and Michael W. Johnson, Reinforcing Deterrence on NATO’s Eastern Flank (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2016); “Demystifying the A2/AD Buzz,” War on the Rocks, last modified January 4, 2017, accessed September 24, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/01/demystifying-the-a2ad-buzz/.

[20] Rod Thornton and Manos Karagiannis, “The Russian Threat to the Baltic states: The Problems of Shaping Local Defense Mechanisms,” The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 29, no. 3 (2016), 331-351. The idea behind plausible deniability states that Russia will only make use of means to disrupt Western forces if they cannot explicitly trace their origins back to Russia and that they cannot hold Russia accountable for these actions. This, in turn, leads to insecurity among NATO allies and prevents the alliance from taking collective action.

[21] “German Waters Teeming with WWII Munitions,” Der Spiegel, last modified April 11, 2013, accessed November 25, 2017, http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/dangers-of-unexploded-wwii-munitions-in-north-and-baltic-seas-a-893113.html.

[22] Martin Murphy, Frank G. Hoffman and Gary Jr Schaub, Hybrid Maritime Warfare and the Baltic Sea Region (Copenhagen: Centre for Military Studies (University of Copenhagen), 2016), 10.

[23] “The Russia – NATO A2AD Environment,” Center for Strategic & International Studies, last modified January 3, 2017, accessed September 23, 2017, https://missilethreat.csis.org/russia-nato-a2ad-environment/.

[24] “Russia could Block Access to Baltic Sea, US General Says,” Defense One, last modified December 9, 2015, accessed September 23, 2017, http://www.defenseone.com/threats/2015/12/russia-could-block-access-baltic-sea-us-general-says/124361/.

[25] Frank G. Hoffman, Assessing Baltic Sea Regional Maritime Security (Philadelphia: Foreign Policy Research Institute, 2017), 6.

[26] Federal Ministry of Defence, White Paper on German Security Policy and the Future of the Bundeswehr (Berlin: Federal Ministry of Defence, 2016), 50.

[27] Murphy, Hoffman and Schaub, Hybrid Maritime Warfare and the Baltic Sea Region.

[28] Bruns, The Baltic Sea and Current German Naval Strategy.

[29] Andreas Schmidt, “Countering Anti-Access/Area Denial: Future Capability Requirements in NATO,” JAPCC Journal 23 (Autumn/Winter, 2016), 69-77.

[30] Hicks et al., Undersea Warfare in Northern Europe.

[31] Hicks et al., Undersea Warfare in Northern Europe.

[32] “All of Germany’s Submarines are Currently Down,” DefenseNews, last modified October 20, 2017, accessed November 21, 2017, https://www.defensenews.com/naval/2017/10/20/all-of-germanys-submarines-are-currently-down/.

[33] Talmadge, Closing Time: Assessing the Iranian Threat to the Strait of Hormuz, 82-117, 98.

[34] “Russian Warships in Latvian Exclusive Economic Zone: Confrontational, Not Unlawful,” Center for International Maritime Security, last modified May 15, 2017, accessed September 23, 2017, https://cimsec.org/russian-warships-latvias-exclusive-economic-zone-confrontational-not-unlawful/32588.

[35] “Russian Jet’s Passes Near U.S. Ship in Black Sea ‘Provocative’ -Pentagon,” Reuters, last modified April 14, 2014, accessed September 23, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/usa-russia-blacksea/update-1-russian-jets-passes-near-u-s-ship-in-black-sea-provocative-pentagon-idUSL2N0N60V520140414.

[36] “Sweden Steps Up Hunt for “Foreign Underwater Activity”,” Reuters, last modified October 18, 2014, accessed September 23, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-sweden-deployment/sweden-steps-up-hunt-for-foreign-underwater-activity-idUSKCN0I70L420141018.

[37] “Russia Says its Baltic Sea War Games with Chinese Navy Not a Threat,” Reuters, last modified July 26, 2017, accessed September 23, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-china-wargame/russia-says-its-baltic-sea-war-games-with-chinese-navy-not-a-threat-idUSKBN1AB1D6.

Featured Image: Russian troops load an Iskander missile. (Sputnik/ Sergey Orlov)