The following selections are derived from an article originally published in the Naval War College Review under the title, “Kamikazes: The Soviet Legacy.” Read it in its original form here.

Read Part One here.

By Maksim Y. Tokarev

As it was, the crews of the field-parked Backfires, in the best aviation tradition, had to accept the primary flight data during briefings in the regiments’ ready rooms. Of course, they had the preliminary plans and knew roughly the location of the incoming air-sea battle and the abilities of the enemy—the task force’s air defenses. In fact, the sorties were carefully planned, going in. But planning was very general for the way out. The following conversation in the ready room of the MRA ’s 183rd Air Regiment, Pacific Fleet NAF, which occurred in the mid-1980s, shows this very honestly. A young second lieutenant, a Backfire WSO fresh from the air college, asked the senior navigator of the regiment, an old major: “Sir, tell me why we have a detailed flight plan to the target over the vast ocean, but only a rough dot-and-dash line across Hokkaido Island on way back?” “Son,” answered the major calmly, “if your crew manages to get the plane back out of the sky over the carrier by any means, on half a wing broken by a Phoenix and a screaming prayer, no matter whether it’s somewhere over Hokkaido or directly through the moon, it’ll be the greatest possible thing in your entire life!” There may have been silent laughter from the shade of a kamikaze in the corner of the room at that moment.

The home fields of MRA units were usually no more than 300 kilometers from the nearest shoreline (usually much less). Each air regiment had at least two airstrips, each no less than 2,000 meters long, preferably concrete ones, and the Engineering Airfield Service could support three fully loaded sorties of the entire regiment in 36 hours. The efforts of shore maintenance were important, as all the missiles, routinely stored in ordnance installations, had to be quickly fueled and prepared for attachment to the planes before takeoff.

The takeoff of the regiment usually took about half an hour. While in the air, the planes established the cruise formation, maintaining strict radio silence. Each crew had the targeting data that had been available at the moment of takeoff and kept the receivers of the targeting apparatus ready to get detailed targeting, either from the air reconnaissance by voice radio or from surface ships or submarines. The latter targeting came by high-frequency (HF) radio, a channel known as KTS Chayka (the Seagull short-message targeting communication system) that was usually filled with targeting data from the MRSC Uspekh (the Success maritime reconnaissance targeting system), built around the efforts of Tu-95RC reconnaissance planes. The Legenda (Legend) satellite targeting system receiver was turned on also, though not all planes had this device. The Backfire’s own ECM equipment and radar-warning receivers had to be in service too. With two to four targeting channels on each plane, none of them radiating on electromagnetic wave bands, the crowd of the Backfires ran through the dark skies to the carrier task force.

Where Are Those Mad Russians?

Generally, detailed data concerning the U.S. air defense organization were not available to Soviet naval planners. What they knew was that F-4, and later F-14 planes could be directed from three kinds of control points: the Carrier Air Traffic Control Center on the carrier itself, an E-2 aloft, or the Air Defense Combat Center of one of the Aegis cruisers in formation. Eavesdropping on the fighter-direction VHF and ultra high-frequency radio circuits by reconnaissance vessels and planes gave Soviet analysts in 1973–74 roughly the same results as were subsequently noted by late Vice Admiral Arthur Cebrowski: “Exercise data indicated that sometimes a squadron of F-14s operating without a central air controller was more effective in intercepting and destroying attackers than what the algorithms said centralized control could provide.”

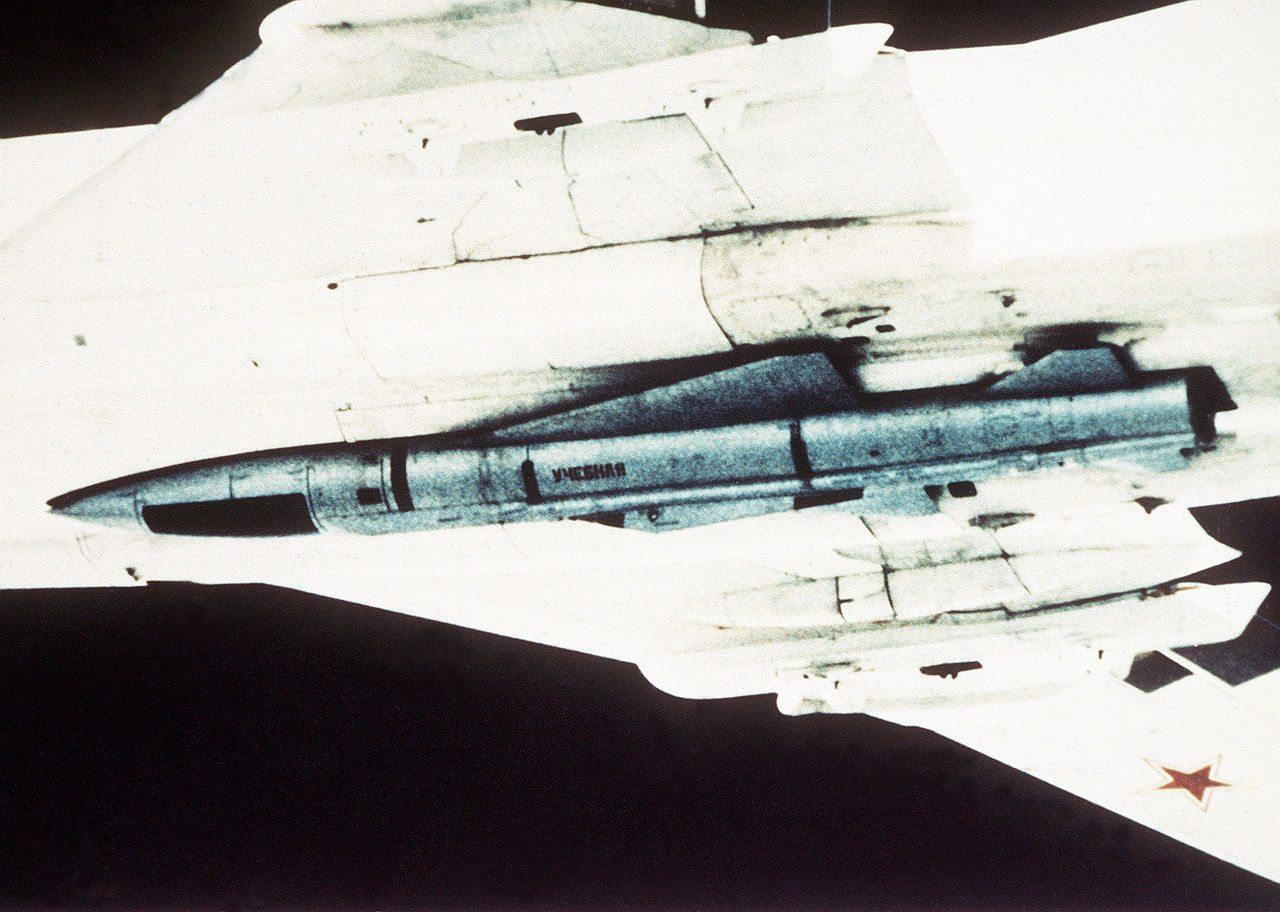

SNAF planners found that interceptor crews were quite dependent on the opinions of air controllers or FDOs, even in essence psychologically subordinate to them. So the task of the attackers could be boiled down to finding a way to fool those officers—either to overload their sensors or, to some degree, relax their sense of danger by posing what were to their minds easily recognizable decoys, which were in reality full, combat-ready strikes. By doing so the planners expected to slow the reactions of the whole air defense system, directly producing the “golden time” needed to launch the missiles. Contrary to widespread opinion, no considerable belief was placed in the ability of launched missiles to resist ECM efforts, but the solid and partially armored airframe of the Kh-22 could sustain a significant number of the 20mm shells of Close-In Weapon System (CIWS) guns. (Given the even more rigid airframe of the submarine-launched missiles of the Granit family —what NATO called the SS-N-19 Shipwreck—it would have been much better for the U.S. Navy to use a CIWS of at least 30mm caliber.)

Things could become even worse for the carriers. In some plans, a whole VVS fighter air regiment of Su-15TM long-range interceptors would have escorted the MRA division, so that the F-14s over the task force might have been overwhelmed and crowded out by similar Soviet birds. Though the main targets for the Sukhois, which as pure interceptors were barely capable of dogfighting, were the E-2 Hawkeyes, it is possible that some F-14s could have become targets for their long-range air-to-air missiles with active radar seeker (such as R-33, similar to the AIM-54). Sure enough, no Sukhoi crews had been expected to return, mainly because of their relatively limited range and the fact that they, mostly unfamiliar with long flights over the high seas, depended on the bomber crews’ navigation skills.

Long before reaching the target, at a “split” position approximately 500 kilometers from the carrier task force, and if the target’s current position had been somehow roughly confirmed, the air division’s two regimental formations would divide into two or three parts each. The WSO of each plane adopted his own battle course and altitude and a flight plan for each of his missiles. As we have seen, the early versions of Kh-22 had to acquire the target while on the plane’s hardpoints, making this a terrible job very close to that of a World War II kamikaze, because between initial targeting of the carrier by the plane’s radar and missile launch the Backfire itself was no more than a supersonic target for AIM-54s.

The more Phoenixes that could be carried by a single interceptor, the more Backfires that could be smashed from the sky prior to the launch of their Kh-22s. So if the Backfires were the only real danger to U.S. carriers up to the fall of the USSR , it would have been much better for the U.S. Navy to use the F-111B [carrier-based interceptor], a realization of the TFX (Tactical Fighter Experimental) concept, than the F-14. A Tomcat could evidently carry the same six Phoenixes as an F-111B, but there were the data that the “Turkey” could not bring all six back to the carrier, owing to landing-weight limitations. Imagine a fully loaded Tomcat with six AIM-54s reaching its “bingo point” (limit of fuel endurance) while on barrier CAP station, with air refueling unavailable. The plane has to land on the carrier, and two of its six missiles have to be jettisoned. Given the alternating sorts of approaches by Backfire waves, reducing the overall number of long-range missiles by dropping them into the sea to land F-14s safely seems silly. Admiral Thomas Connolly’s claims in the 1960s that killed the F-111B in favor of the F-14 (“There isn’t enough power in all Christendom to make that airplane what we want!”) could quite possibly have cost the U.S. Navy a pair of carriers sunk.

The transition of the U.S. Navy from the F-14 to the F/A-18 made the anti-Backfire matter worse. Yes, the Hornet, at least the “legacy” (early) Hornet, is very pleasant to fly and easy to maintain, but from the point of view of range and payload it is a far cry from the F-111B. How could it be otherwise for a jet fighter that grew directly from the lightweight F-5? Flying and maintaining naval airplanes are not always just for fun; sometimes it takes long hours of hard work to achieve good results, and it had always been at least to some degree harder for naval flyers than for their shore-based air force brethren doing the same thing. Enjoying the Hornet’s flying qualities at the expense of the Phoenix’s long-range kill abilities is not a good tradeoff. Also, the Hornet (strike fighter) community evidently has generally replaced its old fighter ethos with something similar to the “light attack,” “earthmover” philosophy of the Vietnam-era A-4 (and later A-7) “day attack” squadrons; all the wars and battle operations since 1990 seem to prove it. It is really good for the present situation that the ethos of F/A-18 strike fighter pilots is not the self-confident bravado of the F-14 crews but comes out of more realistic views. Yet for the defense of carrier task forces, it was not clever to abandon the fast, heavy interceptor, able to launch long-range air-to-air missiles—at least to abandon it completely.

To fool the FDOs, the incoming Backfires had to be able to saturate the air with chaff. Moreover, knowing the position of the carrier task force is not the same as knowing the position of the carrier itself. There were at least two cases when in the center of the formation there was, instead of the carrier, a large fleet oiler or replenishment vessel with an enhanced radar signature (making it look as large on the Backfires’ radar screens as a carrier) and a radiating tactical air navigation system. The carrier itself, contrary to routine procedures, was steaming completely alone, not even trailing the formation.

To know for sure the carrier’s position, it was desirable to observe it visually. To do that, a special recce-attack group (razvedyvatel’no-udarnaya gruppa, RUG) could be detached from the MRA division formation. The RUG consisted of a pair of the Tu-16R reconnaissance Badgers and a squadron of Tu-22M Backfires. The former flew ahead of the latter and extremely low (not higher than 200 meters, for as long as 300–350 kilometers) to penetrate the radar screen field of the carrier task force, while the latter were as high as possible, launching several missiles from maximum range, even without proper targeting, just to catch the attention of AEW crews and barrier CAP fighters. Meanwhile, those two reconnaissance Badgers, presumably undetected, made the dash into the center of the task force formation and found the carrier visually, their only task to send its exact position to the entire division by radio. Of course, nobody in those Badgers’ crews (six or seven officers and men per plane) counted on returning; it was 100 percent a suicide job.

After the RUG sent the position of the carrier and was shattered to debris, the main attack group (UG, udarnaya gruppa) launched the main missile salvo. The UG consisted of a demonstration group, an ECM group armed with anti-radar missiles of the K-11 model, two to three strike groups, and a post-strike reconnaissance group. Different groups approached from different directions and at different altitudes, but the main salvo had to be made simultaneously by all of the strike groups’ planes. The prescribed time slot for the entire salvo was just one minute for best results, no more than two minutes for satisfactory ones. If the timing became wider in an exercise, the entire main attack was considered unsuccessful.

Moreover, in plans, three to five planes in each regimental strike had to carry missiles with nuclear warheads. It was calculated that up to twelve hits by missiles with regular warheads would be needed to sink a carrier; by contrast, a single nuclear-armed missile hit could produce the same result. In any case, almost all Soviet anti-carrier submarine assets had nuclear-armed anti-carrier missiles and torpedoes on board for routine patrols.

Having launched their missiles, it was up to the crews, as has been noted above, to find their way back. Because of the possibility of heavy battle damage, it was reasonable to consider the use of intermediate airfields and strips for emergency or crash landings, mainly on the distant islands, even inhabited ones, in the Soviet or Warsaw Pact exclusive economic zones. The concept of using the Arctic ice fields for this purpose was adopted, by not only the MRA but the VVS (interceptors of the Su-15, Tu-128, and MiG-25/31 varieties) too. Though the concept of maintaining such temporary icing strips had been accepted, with the thought that planes could be refueled, rearmed, and even moderately repaired in such a setting, it was not a big feature of war plans. The VVS as a whole was eager to use captured airfields, particularly ones in northern Norway, but the MRA paid little attention to this possibility, because the complexity of aerodrome maintenance of its large planes, with their intricate weapons and systems, was considered unrealistic at hostile bases, which would quite possibly be severely damaged before or during their capture.

All in all, the expected loss rate was 50 percent of a full strike—meaning that the equivalent of an entire MRA air regiment could be lost in action to a carrier task force’s air defenses, independent of the strike’s outcome.

An Umi Yukaba for the Surface and Submarine Communities

Although the first massive missile strikes on carrier task forces had to be performed by SNAF/DA forces, there were at least two other kinds of missile carriers in the Soviet Navy. The first were guided-missile ships, mostly in the form of cruisers (CGs), those of Project 58 (the NATO Kynda class), Project 1144 (Kirov class), and Project 1164 (Slava class). Moreover, all the “aircraft-carrying cruisers” of Project 1143 (the Kiev class, generally thought of as aircraft carriers in the West) had the same anti-ship cruise missiles as the CGs of Project 1164. Also, the destroyers of Project 956 (Sovremenny class) could be used in this role, as well as all the ships (the NATO Kresta and Kara classes) armed with ASW missiles of the Type 85R/RU/RUS (Rastrub/Metel, or Socket/Snowstorm) family, which could be used in an anti-ship mode. The main form of employment of guided missile ships was the task force (operativnoye soedinenie, in Russian), as well as the above-noted direct-tracking ship or small tactical groups of ships with the same job (KNS or GKNS, respectively, in Russian).

The other anti-carrier missile carriers were nuclear-powered guided-missile submarines (SSGNs), in a vast number of projects and types, using either surface or submerged launch. The most deadly of these were the Project 949A boats (NATO Oscar IIs), with P-700 Granit missiles. (The SSGN Kursk, recently lost to uncertain causes, was one of them.) The operational organization for the submarine forces performing the anti-carrier mission was the PAD (protivo-avianosnaya divisiya, anticarrier division), which included the SSGNs, two for each target carrier, and nuclear-powered attack submarines for support. In sum, up to fifteen nuclear submarines would deploy into the deep oceans to attack carrier task forces. One PAD was ready to be formed from the submarine units of the Northern Fleet, and one, similarly, was ready to assemble in the Pacific Fleet.

A detailed description of the tactics and technologies of all those various assets is beyond the aim of this article, but one needs an idea of how it worked as a whole. The core of national anti-carrier doctrine was cooperative usage of all those reconnaissance and launch platforms. While they understood this fact, the staffs of the Soviet Navy had no definite order, manual, or handbook for planning anti-carrier actions except the “Tactical Guidance for Task Forces” (known as TR OS-79), issued in 1979 and devoted mainly to operational questions of surface actions, until 1993, when “Tactical Guidance for Joint Multitype Forces” entered staff service. The latter document was the first and ultimate guidance for the combined efforts of the MRA , surface task forces, and submerged PADs, stating as the overall goal the sinking of the designated target carriers at sea with a probability of 85 percent.

It is no secret that the officers of the surface community who served on the guided-missile ships counted on surviving a battle against a U.S. Navy carrier air wing for twenty or thirty minutes and no more. In reality, the abilities of the surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) installed on the ships were far less impressive than the fear they drew from U.S. experts. For example, the bow launcher of the Storm SAM on the Kresta– and Kara-class ASW destroyers shared a fire-control system with the Metel ASW missile. It would be quite possible for U.S. aircraft to drop a false sound target (imitating a submarine) ahead of the Soviet formation to be sure that the bow fire-control radars would be busy with the guidance of ASW missiles for a while. The bow SAM launchers of the destroyers of these classes would be useless all this time, allowing air attacks from ahead. Even “iron” bombs could mark the targets.

SSGNs were evidently considered in the West to be the safest asset of the Soviet Navy during an attack, but it was not the case. The problem was hiding in the radio communications required: two hours prior to the launch, all the submarines of the PAD were forced to hold periscope depth and lift their high frequency-radio and satellite communication antennas up into the air, just to get the detailed targeting data from reconnaissance assets directly (not via the staffs ashore or afloat); targeting via low- or very-low-frequency cable antennas took too much time and necessarily involved shore transmitting installations, which could be destroyed at any moment. There was little attention paid to buoy communication systems (because of the considerable time under Arctic ice usual for Soviet submarines). Thus the telescoping antennas in a row with the periscopes at the top of the conning tower were the submarine’s only communication means with the proper radio bandwidth. Having all ten or fifteen boats in a PAD at shallow depth long before the salvo was not the best way to keep them secure. Also, the salvo itself had to be carried out in close coordination with the surface fleet and MRA divisions.

However, the main problem was not the intricacy of coordination but targeting —that is, how to find the carrier task forces at sea and to maintain a solid, constant track of their current positions. Despite the existence of air reconnaissance systems such as Uspekh, satellite systems like Legenda, and other forms of intelligence and observation, the most reliable source of targeting of carriers at sea was the direct-tracking ship. Indeed, if you see a carrier in plain sight, the only problem to solve is how to radio reliably the reports and targeting data against the U.S. electronic countermeasures. Ironically, since the time lag of Soviet military communication systems compared to the NATO ones is quite clear, the old Morse wireless telegraph used by the Soviet ships was the long-established way to solve that problem. With properly trained operators, Morse keying is the only method able to resist active jamming in the HF band. For example, the Soviet diesel-electric, Whiskey-class submarine S-363, aground in the vicinity of the Swedish naval base at Karlskrona in 1981, managed to communicate with its staff solely by Morse, despite a Swedish ECM station in the line of sight. All the other radio channels were effectively jammed and suppressed. While obsolete, strictly speaking, and very limited in information flow, Morse wireless communication was long the most serviceable for the Soviet Navy, owing to its simplicity and reliability.

But the direct tracker was definitely no more than another kind of kamikaze. It was extremely clear that if a war started, these ships would be sent to the bottom immediately. Given that, the commanding officer of each had orders to behave like a rat caught in a corner: at the moment of war declaration or when specifically ordered, after sending the carrier’s position by radio, he would shell the carrier’s flight deck with gunfire, just to break up the takeoff of prepared strikes, fresh CAP patrols, or anything else. Being usually within the arming zone of his own anti-ship missiles and having no time to prepare a proper torpedo salvo, the “D-tracker’s” captain had to consider his ship’s guns and rocket-propelled depth charges to be the best possible ways to interfere with flight deck activity. He could even ram the carrier, and some trained their ship’s companies to do so; the image of a “near miss,” of the bow of a Soviet destroyer passing just clear of their own ship’s quarter is deeply impressed in the memory of some people who served on board U.S. aircraft carriers in those years.

Lieutenant Commander Tokarev joined the Soviet Navy in 1988, graduating from the Kaliningrad Naval College as a communications officer. In 1994 he transferred to the Russian Coast Guard. His last active-duty service was on the staff of the 4th Coast Guard Division, in the Baltic Sea. He was qualified as (in U.S. equivalents) a Surface Warfare Officer/Cutterman and a Naval Information Warfare/Cryptologic Security Officer. After retirement in 1998 he established several logistics companies, working in the transport and logistics areas in both Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States.

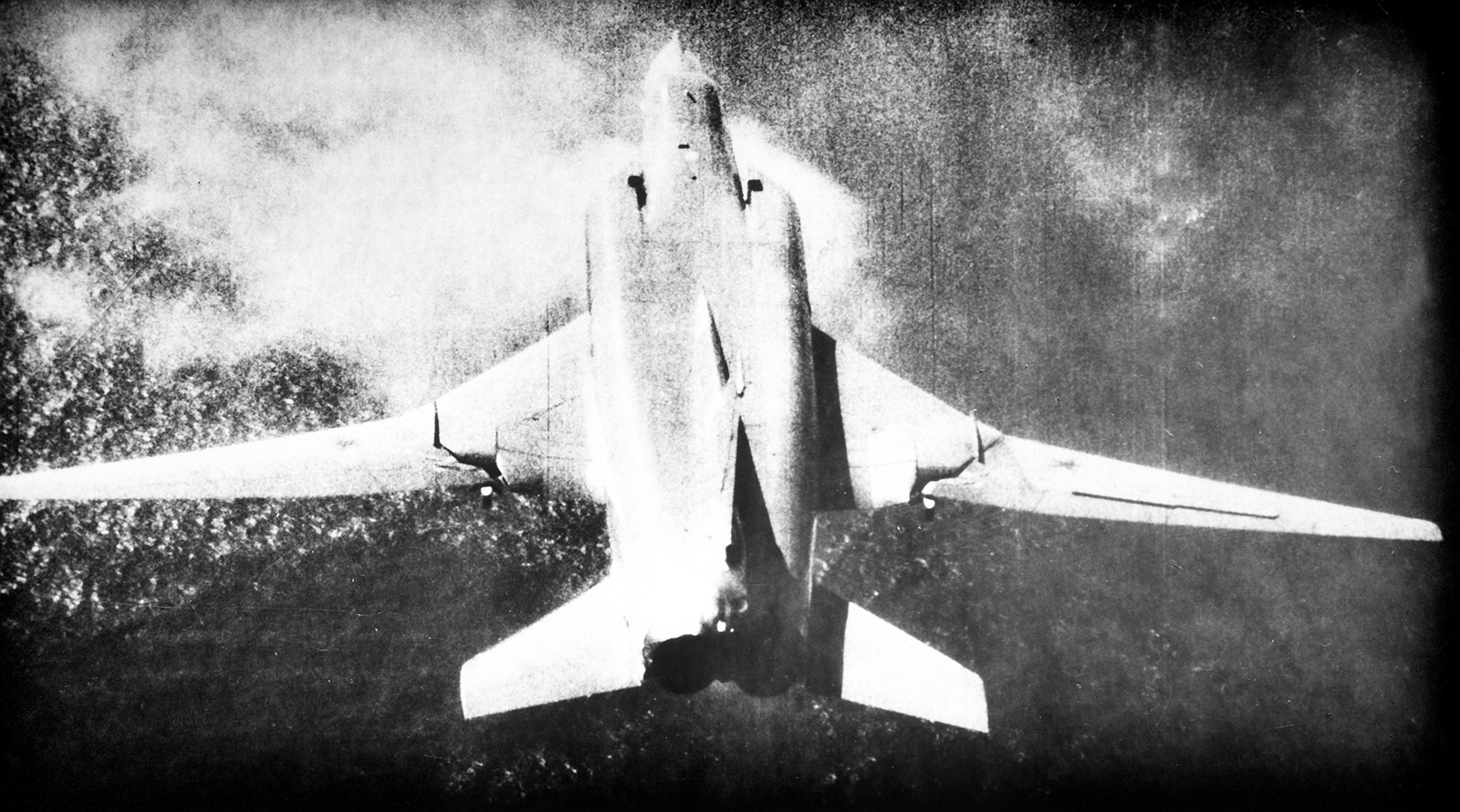

Featured Image: March 3, 1986 – A left underside view of a Soviet Tu-22 Backfire aircraft in flight. (Photo via U.S. National Archives)