The following selections are derived from an article originally published in the Naval War College Review under the title, “Kamikazes: The Soviet Legacy.” Read it in its original form here.

By Maksim Y. Tokarev

The Naval Air Force of the Soviet Navy: The Admirals’ Stepchild

Despite the fact that Russian military aviation was born within the navy, since 1922—when the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the USSR, was created— until today the Naval Air Force has been essentially the representative office of the Soviet/Russian Air Force (Voyenno-Vozdushnie Sily, or VVS ) in the navy realm. Russian naval aviation has not possessed two features that distinguish naval air forces from those of the army or “big” national air force counterparts:

- A system of development, design, and purchase of aircraft and weapons

- A system of education and training of flying personnel (from 1956 onward).

All such systems were and are still mostly in the hands of the air force (during World War II, an army air force, known as the VVS -RKKA).

Technically, the Soviet Naval Air Force (SNAF) was part of the navy. But in fact, SNAF fixed-wing planes, with a handful of exceptions—such as the vertical/ short-takeoff-and-landing (VSTOL ) light-attack Yak-38 and a small family of seaplanes of the Beriev Aircraft Company (the Be-6, Be-12, Be-200)—were, as they still are, ordered by and developed for the air force. All the huge long-range, heavy bombers, such as the Tu-16 (NATO Badger family), the Tu-95 (Bear), and the Tu-22 (Backfire), were developed under the orders and specifications of the Soviet Air Force’s bomber command, the DA (Dal’naya Aviatsiya, or Long-Range Aviation). Moreover, the DA’s heavy bomber units constituted an integral part of the anti-carrier doctrine, representing nearly a third of the forces that would be involved in strikes. Those units could temporarily fall under operational control of the SNAF. Two-thirds of the rest were organized as the MRA (Morskaya Raketonosnaya Aviatsiya, or Naval Guided-Missile Aviation), permanently under the operational and administrative control of the navy.

But this administrative interconnection did not remove the curtain between the navy’s philosophy and ethos and those of the VVS. Soviet naval aviators, all commissioned officers, held field rank instead of deck (naval) rank and were completely out of the chain of command of naval surface ships, units, and staffs, let alone submarines. Their areas of responsibility and service were almost exclusively aviation matters. Each of the four fleet staffs, typically headed by a full admiral (three stars) or a vice admiral (two stars), had a subordinate Staff of Naval Aviation of the X Fleet (where X would be Baltic, Northern, Black Sea, or Pacific), which commanded all the fleet’s air units. For each fleet’s commanding general of aviation, typically a major general or lieutenant general, to whom this staff reported, there was only one possible next career step within the navy: to become commanding general of Naval Aviation of the Soviet Navy in the Naval Main Staff in Moscow, as a colonel general.

Needless to say then, almost all naval aviators and naval air navigators (roughly similar to American naval flight officers) from the beginning of their careers kept their eyes the other way—toward an interservice transfer to the VVS, where they could reach much higher command assignments, as air marshals. Moreover, all of them had friends in the VVS, because the navy did not have its own system of pilot and navigator training courses, schools, or academies. All naval aviators, navigators, and aviation engineers were (and still are) graduates of VVS air military colleges or air military engineering colleges. So not only were they aware that they represented a marginal part of the annual alumni pool, having chosen the restricted SNAF path instead of the wide-open VVS, but their early military and flying experience, the four or five years spent in an air college, had filled them with VVS ethos and traditions instead of the navy’s. It is worth noting that, contrary to U.S. military aviation training practice, Soviet/Russian VVS air colleges inserted cadets into the flying pipeline roughly in the middle of the course, two years before graduation and commissioning. All Soviet military pilots could fly the modern military aircraft in almost all circumstances months before the little stars of a second lieutenant were on their shoulders. There are close parallels to British Royal Air Force (RAF ) practice and ethos, and to those of the World War II Luftwaffe as well…

…This semi-separation of the SNAF from the navy created, without doubt, neglect on the part of the “true” naval officer communities, surface and submarine. Given the rule that no naval aviator or navigator could attain flag rank in any of the fleet staffs and that the admirals and deck-grade officers of the Soviet Navy only occasionally flew on board naval aircraft, and then as passengers only, there was no serious trust in the SNAF in general or its anti-carrier role in particular. The SNAF, though its actions were coordinated with surface and submarine units in war plans and staff training, would attack on its own, whereas missile-firing surface units and submarines had to complement each other, depending on overall results.

The actual training of SNAF units had no significant connection with surface or submarine units below the level of “type” staffs of the fleet. Communications between SNAF aircraft aloft and guided-missile cruisers at sea or even with shore radio stations maintaining submarine circuits often failed because of mistakes in frequencies or call signs. So the “real” admirals’ common attitude toward the MRA was essentially the same as that toward shore-based missiles: order them to take off, heading for the current target position, and forget them. No wonder that the kamikaze spirit was often remembered in the ready rooms of MRA units ashore.

The Soviet Navy had itself experienced the real thing once, in 1945, in the last month of the war. While supporting an amphibious landing on the Kurile Islands, a small group of Soviet ships was attacked by several B5N2 Kate torpedo bombers from the Kurile-based Hokuto Kokutai, an outfit normally devoted to patrol and ASW over the surrounding sea. According to Japanese records, at the time of the attacks only five Kates from that unit were flyable, and four of them participated in kamikaze attacks against the Soviet amphibious assaults, armed with 200-kilogram depth charges or 60-kilogram general-purpose bombs. On 12 August two of these planes were shot down by AA fire from the minesweeper T-525 (a U.S.-built AM type), and one crashed directly into the small motor minesweeper KT-152 (a mobilized fishing boat), which immediately sank with all hands. This was the only successful kamikaze encounter in Soviet naval history.

Why Should We Attack the U.S. Carriers— and for God’s Sake, How?

Unable to create a symmetrical aircraft carrier fleet, for both economic and political reasons, the Soviet Navy had to create some system that could at least deter the U.S. Navy carrier task forces from conducting strikes against the naval, military, and civilian infrastructure and installations on the Kola and Kamchatka Peninsulas, Sakhalin Island, and the shoreline around the city of Vladivostok. The only reasonable way to do so was as old as carrier aviation doctrine itself: conduct the earliest possible strike to inflict such damage that the carrier will be unable to launch its air group, or at least the nuclear-armed bombers. There was also an important inclination to keep the SLOCs in Mediterranean under the threat of massive missile strikes. These plans, given the absence of a Soviet carrier fleet, definitely rode on the wings of land-based aviation. Riding also on the shoulders of air-minded military leaders, they reached out farther than the typical 500-mile combat radius of regular medium bombers, by means of something much more clever than the iron, unguided bombs that had been the main weapon of Soviet bombers for a long time.

The origins of guided anti-ship missiles in military aviation are German. Hs293 missiles and FX1400 guided bombs were successfully employed in 1943–44 by Luftwaffe bomber units; one of only five battleships sunk at sea solely by aviation, the Italian battleship Roma, was sunk by FX1400s dropped and guided by Do-217 crews of Kampfgeschwader (Bomber Squadron) 100. But those weapons, being radio controlled, could have been easily disabled by relatively simple ECM measures, such as jamming, had the ECM operator known the guidance frequency. A more promising method of guidance was active radar seekers, which made such weapons independent of the carrying platform after launch. The first air-to-surface missile with such guidance and targeting was created in Sweden in the early 1950s and entered service with the Swedish air force as the Rb04 family.

Regardless of whether it had the help of intelligence information, the Soviet weapons industry managed to develop its own device at roughly the same time, but using semiactive targeting. The first such missile, the KS-1 Kometa (Comet), started development in 1951 and entered service two years later. From the beginning, and in contrast to all other such systems, Soviet anti-ship missiles were designed to kill carriers and other big ships by hitting pairs. The warhead of the KS-1 contained more than 800 kilograms of explosive, and the missile generally resembled a little unmanned MiG-15 fighter plane. The old Japanese Okha concept had clearly been adopted entirely, with the exception of a sacrificial pilot.

It is worth noting that the nuclear strike/deterrent role was exclusive to U.S. aircraft carriers for less than a single year, from the first assembly of a nuclear bomb on board a carrier in December 1951 to the successful trial launch of a Regulus nuclear cruise missile from a submarine in 1952. The carriers’ shared (i.e., with submarines) nuclear role lasted up to 1964, when George Washington– class ballistic-missile submarines went on patrol on a regular basis.

From that time onward, as Adm. James Stockdale recalls, the primary role of the carrier air groups, even fighter squadrons, became the close support of land combat, as well as land interdiction. The beginning of the Vietnam War featured this mode of employment. SNAF staffs found that the main skills of the carriers’ attack squadrons (medium and light) changed twice. From 1964 to 1974, during the Vietnam War, it was mostly land targets that attack squadrons were intended to strike; from 1975 to the Desert Storm operation in 1990 the carrier attack community shifted its focus to readiness to engage Soviet surface fleets at sea, developing the Harpoon guided-missile family. During the first Iraq war the main effort switched again, to close air support and battlefield interdiction ashore. While it was not going to deal with the carrier attack planes directly, the SNAF was watching with interest the fluctuation in the U.S. Navy’s fleet air-defense inventory and tactics, driven by changes in the targets between the open sea and continental landscapes. It was important to find the difference between the typical CAP tactics at sea and barrier CAP duty offshore, calculating the average times that F-4 and F-14 interceptors remained on station between aerial refueling and rotation of patrols….

…The U.S. carrier task force had first been considered a real threat to Soviet shore targets in 1954, when intelligence confirmed the presence of nuclear weapons (both bombs and Regulus missiles) on board the carriers, as well as planes that could deliver them (AJ-1s and A3Ds). The first anti-carrier asset tested in the air at sea was of American origin—the Tu-4 heavy bomber, a detailed replica of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress. The missile-carrying model, the Tu-4KS, was introduced with the Black Sea Fleet Air Force in 1953. The plane was able to carry two KS missiles and was equipped with a K-1M targeting radar. Because of the need to guide the missile almost manually from the bomber, the aircraft had to penetrate the anti-air warfare killing zone of the task force to as close as 40 kilometers from the carrier or even less. The kamikaze-like fate was abruptly switched from the single pilot of an Okha to the entire crew of a Tu-4KS. Subsequent efforts to develop autonomous active-radar missiles (the K-10, K-16, KSR-2, and finally KSR -5) were more or less unsuccessful. Though the semiactive KS placed the carrying plane under serious threat, it was considerably more reliable than the active-radar missiles.

The next generation of planes was represented by the series known to NATO as the Badger (the Tu-16KS, Tu-16K-10/16, Tu-16KSR, with reconnaissance performed by the Tu-16R, or Badger E). This plane was not the best choice for the job, but it was the only model available at the beginning of the 1960s. The service story of the Badger family is beyond the scope of this article, but it is noteworthy that the overall development of anti-carrier strike doctrine grew on its wings. The first and foremost issue that had to be considered by SNAF staffs was the approach to the target, which involved not only the best possible tactics but the weapon’s abilities too. For a long time, prior to the adoption of antiradiation missiles, and given the torpedo-attack background of MRA units, there was a strong inclination toward low-level attack. Such a tactic comported with the characteristics of the missiles’ jet engines and the poor high-altitude (and low temperature) capabilities of their electronic equipment. The typical altitude for launch was as low as 2,000 meters; that altitude needed to accommodate the missile’s 400-600-meter drop after launch, which in turn was needed to achieve a proper start for its engine and systems. Although the SNAF experimented with high-altitude (up to 10,000 meters) and moderate altitude approaches—and until it had been confirmed that the carrier’s airborne early-warning (AEW) aircraft, the Grumman E-2 Hawkeye, could detect the sea-skimming bombers at twice the missile’s range—the low-level approach was considered the main tactic, at least for half the strike strength.

Flying the Backfire in Distant-Ocean Combat: A One-Way Ticket

The MRA ’s aircraft, such as the Tu-16 missile-launching aircraft and the Tu-95 reconnaissance and targeting aircraft, were relatively slow, and they were evidently not difficult targets for U.S. fighters. They were large targets for the AIM-7 Sparrows shot from F-4 Phantoms. The problem for the aircraft was detection by AEW assets. If E-2 (or U.S. Air Force E-3) crews did their job well, even surface ships, such as the numerous Oliver Hazard Perry–class guided-missile frigates, could contribute to shattering a Soviet air raid. Despite the supersonic speed of the KSR -5 missiles, it was not a big problem to catch the bombers before they reached the launch point….

….The picture changed with the Tu-22M, Tu-22M-2, and Tu-22M-3—the Backfire family—which could reach almost Mach 2…The bird has a crew of just four: pilot, copilot, and two navigators—the first shturman (the destination navigator) and second shturman (the weapons-system operator, or WSO). All of them are commissioned officers, males only, the crew commander (a pilot in the left seat, age twenty-six to thirty) being not less in rank than captain. All the seats eject upward, and the overall survivability of the plane in combat is increased, thanks not only to greater speed but also to chaff launchers, warning receivers, active ECM equipment, and a paired tail gun that is remotely controlled by the second navigator with the help of optical and radar targeting systems. This plane significantly improved the combat effectiveness of the MRA.

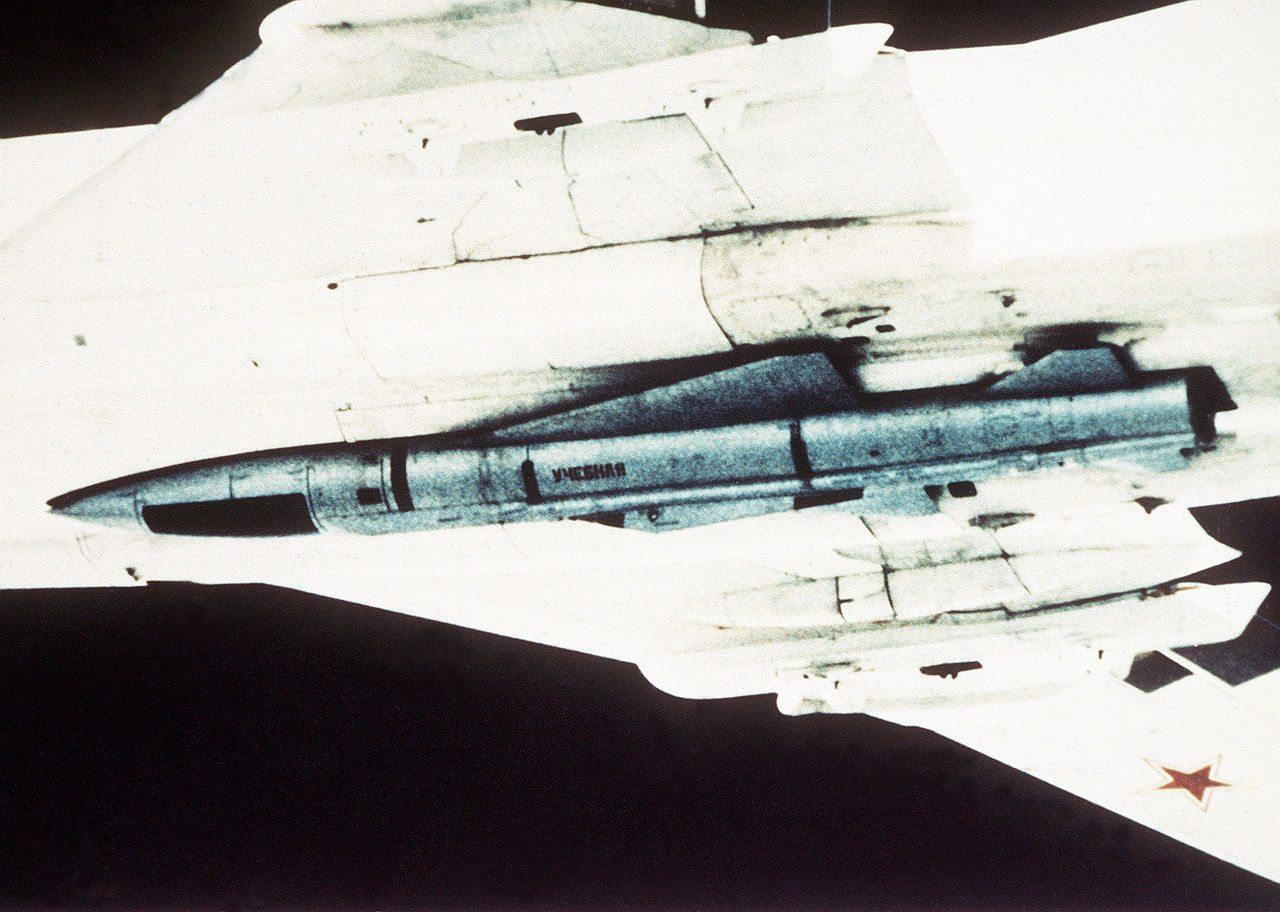

In theory and in occasional training, the plane could carry up to three Kh22MA (or the MA-1 and MA-2 versions) anti-ship missiles, one under the belly and two more under the wings. But in anticipated real battle conditions, seasoned crews always insisted on just one missile per plane (at belly position), as the wing mounts caused an enormous increase in drag and significantly reduced speed and range.

The Kh-22 missile is not a sea skimmer. Moreover, it was designed from the outset as a dual-targeted missile, able to strike radar-significant shore targets, and the latest version can also be employed as an antiradar missile. The first and most numerous model of this missile, the Kh-22MA, had to see the target with its own active radar seeker while still positioned under the bomber’s belly. But the speed, reliability, and power of its warhead are quite similar to those of the Soviet submarine-launched sea skimmers. The price for those capabilities is the usual one for a Soviet weapon—huge weight and dimensions. The Kh-22 is more than 11 meters long and weighs almost six tons, combat ready. The missile can travel at Mach 3 for 400 kilometers. Usually it contains more than a ton of an explosive, but it could carry a 20-200-kiloton nuclear warhead instead.

There is a pool of jokes within the Backfire community about the matter of who is more important in the Tu-22M’s cockpit, pilots or navigators. The backseaters (both the navigators’ compartments are behind the pilots’) often claim that in a real flight the “front men” are usually doing nothing between takeoff and landing, while the shturmans are working hard, maintaining communications, navigating, and targeting the weapon. In reality, the most important jobs are in the hands of the WSO, who runs the communication equipment and ECM sets as well.

The doctrine for direct attacks on the carrier task force (carrier battle group or carrier strike group) originally included one or two air regiments for each aircraft carrier—up to 70 Tu-16s. However, in the early 1980s a new, improved doctrine was developed to concentrate an entire MRA air division (two or three regiments) to attack the task force centered around one carrier. This time there would be a 100 Backfires and Badgers per carrier, between 70 and 80 of them carrying missiles. As the Northern Wedding and Team Spirit exercises usually involved up to three carrier battle groups, it was definitely necessary to have three combat-ready divisions both in northern Russia and on the Pacific coast of Siberia. But at the time, the MRA could provide only two-thirds of that strength—the 5th and 57th MR Air Divisions of the Northern Fleet and the 25th and 143rd MR Air Divisions of the Pacific Fleet. The rest of the divisions needed—that is, one for each region—were to be provided by the VVS DA. The two air force divisions had the same planes and roughly the same training, though according to memoirs of an experienced MRA flyer, Lieutenant General Victor Sokerin, during joint training DA crews were quite reluctant to fly as far out over the open ocean as the MRA crews did, not trusting enough in their own navigators’ skills, and tried to stay in the relative vicinity of the shore. Given the complexity of a coordinated strike at up to 2,000 miles from the home airfield, navigation and communication had become the most important problems to solve.

Being latent admirers of the VVS ethos, MRA officers and generals always tried to use reconnaissance and targeting data provided by air assets, which was also most desired by their own command structure. Targeting data on the current position of the carrier sent by surface ships performing “direct tracking” (a ship, typically a destroyer or frigate, sailing within sight of the carrier formation to send targeting data to attack assets—what the Americans called a “tattletale”), were a secondary and less preferable source. No great trust was placed in reports from other sources (naval radio reconnaissance, satellites, etc.). Lieutenant General Sokerin, once an operational officer on the Northern Fleet NAF staff, always asked the fleet staff ’s admirals just to assign him a target, not to define the time of the attack force’s departure; that could depend on many factors, such as the reliability of targeting data or the weather, that generate little attention in nonaviation naval staff work. The NAF staff had its own sources for improving the reconnaissance and targeting to help plan the sorties properly. Sokerin claims that “no Admirals grown as surface or submarine warriors can understand how military aviation works, either as whole or, needless to say, in details.”

Read Part Two.

Lieutenant Commander Tokarev joined the Soviet Navy in 1988, graduating from the Kaliningrad Naval College as a communications officer. In 1994 he transferred to the Russian Coast Guard. His last active-duty service was on the staff of the 4th Coast Guard Division, in the Baltic Sea. He was qualified as (in U.S. equivalents) a Surface Warfare Officer/Cutterman and a Naval Information Warfare/Cryptologic Security Officer. After retirement in 1998 he established several logistics companies, working in the transport and logistics areas in both Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States.

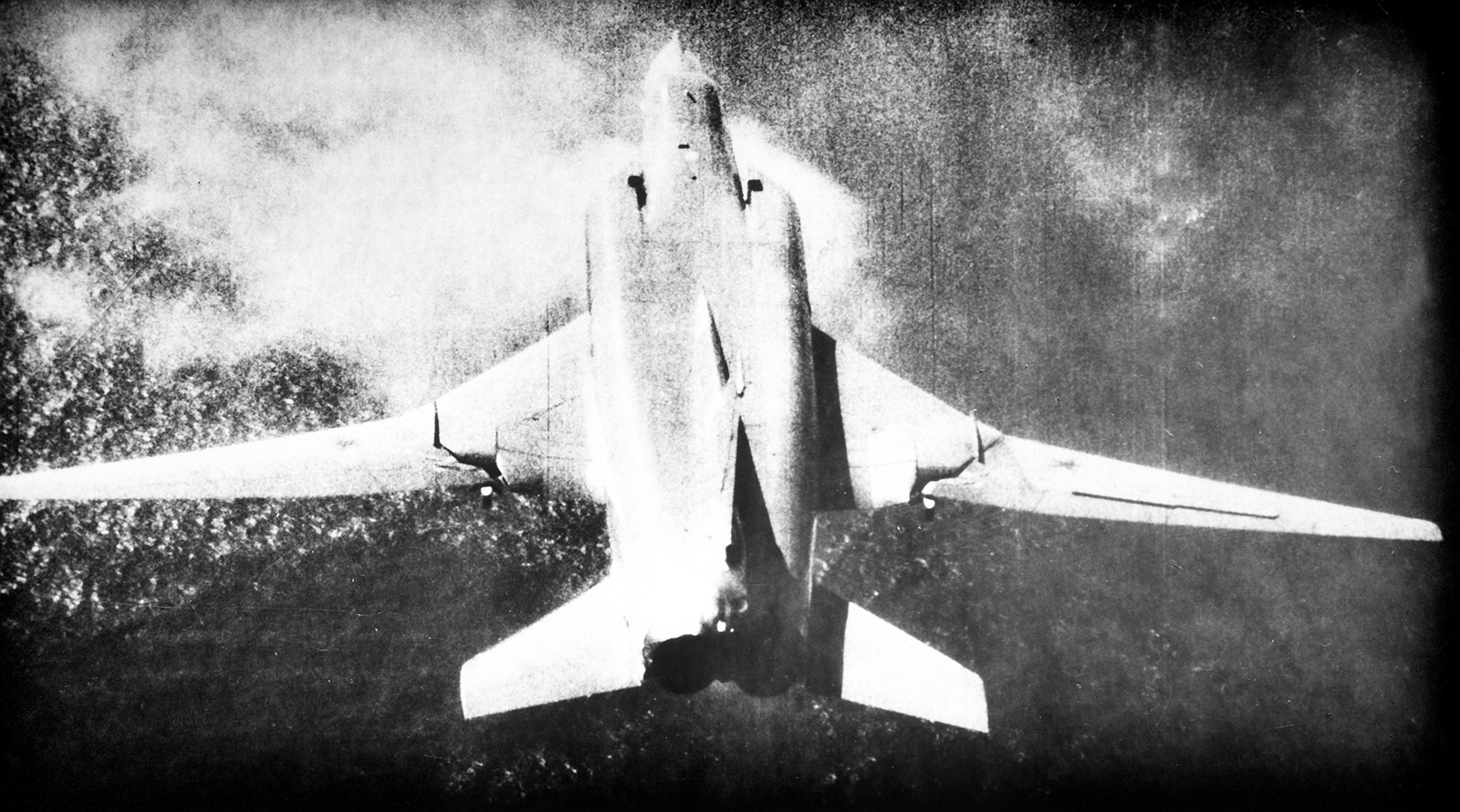

Featured Image: A United Soviet Socialists Republic (Russian) TU-95 Bear bomber aircraft in flight over the Arctic Ocean, during a flight to Keflavik, Iceland in 1983. (U.S. Air Force Photo) (Released)