Tuning into the Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing on September 3, something Secretary Kerry said struck me as very interesting. In response to a question, the Secretary of State said:

“We don’t want to go to war in Syria either. It is not what we are here to ask. The president is not asking you to go to war.”

This statement has received some harsh criticism. See here and here. How we label our involvement directly affects the political perception of what that involvement will be. I think what Secretary Kerry was trying to say was that we are not “putting boots on the ground.” But is there a difference between war and a TLAM strike into Syria?

Under international humanitarian law, or what is more commonly referred to as the law of armed conflict, there are two classifications of conflict: international armed conflict (IAC) and non-international armed conflict (NIAC). An IAC is a conflict between two or more nations. A NIAC is a conflict that only involves one nation and takes place within its own territory. A great example of a NIAC is a civil war, which sufficiently describes the conflict in Syria at the moment. But what happens when the United States uses military force? Does the civil war (a NIAC) evolve into an IAC? Maybe not.

It is possible, under international law, that a TLAM strike into Syria would not be considered a trigger causing an IAC. In the case Nicaragua v. United States, the International Court of Justice determined whether an armed attack had occurred by examining the “scale and effects” of the force used. So what are the “scale and effects” of a TLAM strike? To help determine this, it’s important to understand why the U.S. would launch the strike in the first place.

As heavily reported, the Syrian government used chemical weapons. This is a violation of an international norm and an absence of action would undermine this important norm (notice the difference between “norm” and “law” – a topic for another discussion). The purpose of the TLAM strike then would be to enforce the norm – not to intervene in the civil war or to topple the Assad regime. The “scale and effects” of such a limited strike would be minimal and not likely rise to the level of “armed attack” that would trigger and armed conflict between Syria and the United States. And so long as Syria does not counterstrike, the U.S. would not be moving the conflict in Syria from a NIAC to an IAC. Hence, a “war” between the United States and Syria would still be avoided.

LT Dennis Harbin is a qualified surface warfare officer and is currently enrolled at Penn State Law in the Navy’s Law Education Program. The opinions and views expressed in this post are his alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.

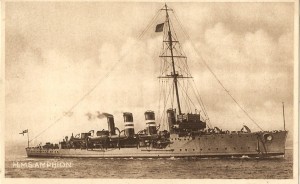

Looking back at Corbett’s writings, he talks a great deal about the need for cruisers, but technology and terminology have moved on and the cruisers of Corbett’s days are not what we think of as cruisers today. Corbett’s “Some Principles of Maritime Strategy” was published in 1911. There were some truly large cruisers built in the years leading up to World War I, but Corbett decried these in that their cost was in conflict with the cruiser’s “essential attribute of numbers.”

Looking back at Corbett’s writings, he talks a great deal about the need for cruisers, but technology and terminology have moved on and the cruisers of Corbett’s days are not what we think of as cruisers today. Corbett’s “Some Principles of Maritime Strategy” was published in 1911. There were some truly large cruisers built in the years leading up to World War I, but Corbett decried these in that their cost was in conflict with the cruiser’s “essential attribute of numbers.”