By Lydelle Joubert

Venezuela has the largest known oil reserves in the world, with 302 billion barrels of proven reserves reported in 2018. Production has however declined from 3.5 million barrels a day in 1997 to 1.4 million barrels in May 2018 due to the persistent economic crisis the country has been facing.

Anzoátegui state is traditionally one of the largest oil production centers in Venezuela. Two thirds of Venezuelan oil is exported through Puerto Jose in Anzoátegui. The concentration of oil industry-related infrastructure in Anzoátegui combined with the declining economic situation and lack of security make it a hotspot for armed robbery at sea in the Caribbean region. Several anchorages lie off the coast of Anzoátegui, such as Bahia De Barcelona Anchorage, Puerto Jose Anchorage and Puerto La Cruz Anchorage. Due to the collapse of the fishing industry, the economic hardship that coastal communities are facing and insufficient security measures at these anchorages, men in small boats approach mostly tankers waiting to load oil and board vessels in order to rob them.

According to the definition of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS, 1982: 61) piracy is limited to acts outside the jurisdiction of the coastal waters of a state. Acts committed in territorial waters are considered armed robbery of ships. As these anchorages are located in Venezuelan territorial waters, it is classified as armed robbery of ships.

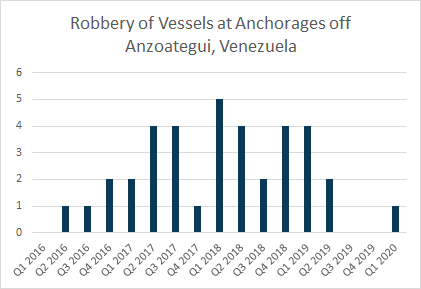

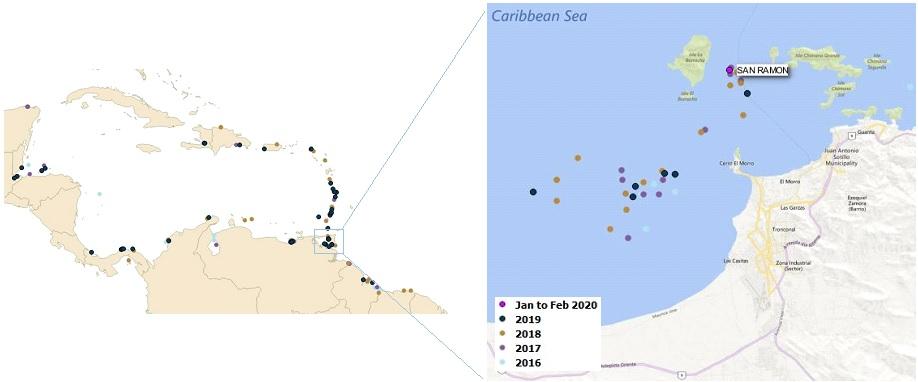

For unknown reasons, reports of armed robbery at these anchorages stopped in the middle of 2019. Between January 2016 and the end of April 2019, 36 robberies and attempted robberies were reported at anchorages off Anzoátegui, of which 29 were on tankers. Six incidents were reported in early 2019, but in April 2019 robberies on commercial ships at these anchorages ended abruptly. No robberies were reported for the next ten months, until the end of February 2020.

What happened in late April or early May 2019 to account for this change? Understanding the cause of this change is important for predicting whether this sharp fall in armed robbery is sustainable or likely to be reversed in the future. Before analyzing potential causes of this sharp decline in armed robberies, it is useful to review what happens in a typical armed robbery at sea in this area.

What Happens in an Armed Robbery at Sea?

Most robberies on ships at these anchorages can be classified as petty theft where a ship’s stores and its crew’s possessions are stolen. Three to seven robbers in small boats approach anchored vessels under darkness and board via the anchor chain and hawse pipe or via a grappling hook and rope. Robbers are usually armed with knives, but guns were observed in a few cases. In a few instances the crew was tied up, threatened, or assaulted and minor injuries were reported.

During a more brazen robbery on 14 October 2018 the bulk carrier Shi Zi Shan was boarded just after midnight by four armed men in national guard uniforms under the ruse of an anti-narcotics inspection. Once aboard they threatened the crew with handguns and commanded them to be taken to the captain’s cabin. They stole all the cash and crew’s valuables.

Most yachts have long since departed this coast, ever since the attacks on these ships turned violent when the Dutch captain of the yacht Mary Eliza was shot and killed at Marina El Concorde in September 2013. These incidents, combined with recent kidnappings of Trinidadian fishermen on the coast of Venezuela, created fear (although unfounded) that piracy and armed robbery off Venezuela could turn into a situation similar to Somalia where crew from commercial vessels are kidnapped from vessels for ransom.

What Contextual Changes Might Account for the Fall in Armed Robberies at Sea?

In January 2018 Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro temporarily closed maritime borders with the ABC islands (Aruba, Bonaire, Curacao). Fresh fruit and vegetables from Venezuela were transported to these islands, but the same routes were also used to smuggle gold, silver, copper and coltan from Venezuela. In February 2019 maritime borders with the ABC islands were once again closed, this time to prevent humanitarian aid from reaching Venezuela from these islands. The measure applied to commercial and fishing vessels. This led to a larger military presence in ports and an increase in vessel inspections on vessels entering ports in an effort to stem the smuggling of aid from the neighboring ABC islands.

At the same time, other economic factors may have reduced shipping traffic and could have reduced opportunities for armed robbery at Puerto Jose. Venezuela suffered from power outages that affected oil production and shipping operations. On 5 April 2019 the U.S. Treasury imposed sanctions on tankers and shipping companies transporting Venezuelan oil to Cuba, which could have further reduced arrivals of vessels at the anchorages. Tankers looking to evade the sanctions would have strong incentives to turn off transponders near Venezuelan water, making it difficult to obtain accurate counts of vessels at these anchorages. This could also dissuade reporting of armed robberies.

However, these explanations are not satisfactory because not all countries adhered to the call for sanctions and Venezuelan vessels were still operating from the port and anchorages. Armed robbers had ample opportunities to commit crimes near Puerto Jose. A closer look reveals that one specific incident may have initiated a chain of events that led to this decline in armed robberies.

How One Act of Defiance May Have Changed Incentives for Armed Robbery

There was one incident that fit the timeframe coinciding with the end of robberies on vessels at these anchorages, but the fact that it spelled a halt of these crimes was quite unintended.

It appears that dissatisfaction is growing amongst mid-level Venezuelan officials who are unhappy with the government for supplying Cuba with oil while severe shortages are experienced within Venezuela. In previous months, nationwide protests were reported at Venezuelan state-owned, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) facilities, leading to a loss of 30 percent in production. On 1 May 2019 a captain of a PDVSA tanker, Manuela Saenz, defied orders to deliver oil to Cuba and notified PDVSA of his intent.

Members of the Bolivarian intelligence service (Sebin) allegedly boarded the products tanker near the Amuay terminal and took control of the vessel. The captain was replaced and Sebin members remained onboard while the delivery to Cuba was made. AIS was also switched off for most of the trip.

Since then, Venezuelan Armed Forces (FANB) have been deployed on 15 PDVSA-operated tankers to ensure that fuel is delivered to Cuba and that crew would not sabotage tankers or divert the product. It is also speculated that armed personnel are placed on the vessels in case the U.S. blocked shipments to Cuba.

This added armed security on these tankers is in all likelihood the determining factor why armed robberies off Anzoátegui stopped at the end of April 2019, but this lull in attacks was short-lived. On 24 February 2020, six armed men wearing balaclavas boarded the tanker San Ramon anchored near Isla Borracha, north of Puerto La Cruz notwithstanding the presence of a coast guard armed guard onboard. This time violence escalated. The captain, Herrera Orozco, resisted the robbers and was shot in the face and killed. Another crewmember is still missing after he jumped overboard, and a coast guard sergeant was injured during the attack.

Conclusion

While we cannot know what caused these armed robbers to be more violent than those involved in previous incidents, it is plausible that this is related to increased security on ships, and the situation escalated. Ships at these anchorages are harder targets than they once were, but the root causes of piracy and armed robbery in Venezuela – including poverty and weak state governance – remain. So long as they do, it is possible that attacks on ships at these anchorages will be dissuaded only as long as criminals can be deterred from employing escalating levels of violence.

Lydelle Joubert is an expert on maritime piracy at Stable Seas, a program of One Earth Future. She has an MA in International Relations from the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Featured Image: Venezuelan military policewoman in a presidential meeting. (Wikimedia Commons)