By Walker D. Mills and Joseph E. Hanacek

“Naval Integration” has quickly become a focus within the U.S. Marine Corps and Navy. It was a critical section in the 38th Commandant of the Marine Corps’ Planning Guidance, where the Commandant elaborated: “I intend to seek greater integration between the Navy and Marine Corps….Navy and Marine Corps officers developed a tendency to view their operational responsibilities as separate and distinct, rather than intertwined…. there is a need to reestablish a more integrated approach to operations in the maritime domain.” Emerging great power competition in the Pacific is again forcing the Marine Corps and the Navy to work more closely and solve complicated new problems. New Marine concepts like Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment and Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations are reintroducing naval operations to the center of Marine thinking and warfighting. Despite this recent shift, there is still a glaring lack of naval-oriented education in the Marines.

Over the last few decades, Marines have increasingly left their naval roots behind and conducted campaigns in the rugged mountains of land-locked Afghanistan and the arid deserts of Iraq. The current generation of Marines is less likely to have served on ship than to have served on the ground in the Middle East. Recent commentary has questioned the true significance of their relationship to the Navy, such as by asking “Are we naval in character or purpose?” A flood of responses revealed, if not a clear answer, at least a resounding acknowledgement that the Marine Corps’ relationship with the Navy is a key attribute, if not the defining attribute of the force. Yet naval campaigns, despite being a raison d’etre for the Marine Corps, do not feature in junior officer education and may not be encountered at all by officers until many years later into their careers. Instead, land operations consist of the grand majority of the material taught. Even in classes on amphibious case studies like the Falklands, Marine instructors often largely if not totally ignore the larger maritime campaign and start with the ship-to-shore movement.

The atrophy of combined Navy and Marine Corps thinking is far from being solely a Marine Corps issue. For years the Navy’s approach to maritime warfare has been built around specialization instead of integration. The aforementioned Marines learning about the Falklands campaign didn’t focus on the war at sea because that was the fleet’s specialty, not theirs. The same can be true of the fight on the ground from the perspective of the Navy. While this type of unilateral approach to problem solving has been sufficient in the era of unchallenged U.S. maritime supremacy, it can no longer be accepted given the growing scope and complexity of potential military challenges.

One of the most valuable attributes of a well-integrated team is its resilience. While some efficiency may be lost in cross-training, traits such as adaptability, effectiveness, and survivability can be greatly enhanced. Marines need to understand amphibious and sea control operations in the context of larger naval campaigns, especially because the modern character of those campaigns is evolving into a far more threatening challenge. Marines need to have a basic literacy of naval strategy, operations, and tactics as it pertains to their roles in supporting those campaigns. This effort not only enhances the fleet when campaigns are functioning well, but it provides the fleet with an insurance policy when combat friction begins to manifest.

Naval integration is not a passing fad, nor a flavor of the day. It is supposed to be the core attribute of the Marine Corps. The meat of the Title 10 roles and responsibilities of the Marine Corps are: “The Marine Corps shall be organized, trained, and equipped to provide fleet marine forces… for service with the fleet… as may be essential to the prosecution of a naval campaign.” The Marine Corps is a force designed to operate in support of and in conjunction with the U.S. Navy.

In this vein, we have assembled a short reading list focused along the theme of naval integration. These readings can serve as a primer in naval operations for Marines and other landlubbers, or supplement and advance a foundation of naval knowledge for any interested reader. The books generally fall into three categories – fundamentals, history, and current issues. We have also included our favorite periodicals that often run articles and debates oncontemporary tactics and proposals for future concepts.

These readings of interest include:

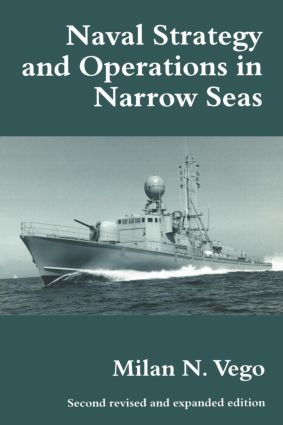

Naval Strategy and Operations in Narrow Seas by Milan Vego

Vego, a professor at the United States Naval War College, may be the world’s leading scholar of littoral warfare. In Naval Strategy and Operations in Narrow Seas, Vego melds his own experience serving in the Adriatic with the Yugoslavian Navy, naval history, and more current naval operations. His book is a comprehensive examination of littoral warfare for the student or practitioner and covers everything from the space and geometries of the littoral to sea denial and relevant weapons systems. It is a perfect book to use both as an introduction and a deeper dive into littoral warfare. However, originally published in 1999, Vego’s book has not been updated to reflect geopolitical and technological changes.

Vego, a professor at the United States Naval War College, may be the world’s leading scholar of littoral warfare. In Naval Strategy and Operations in Narrow Seas, Vego melds his own experience serving in the Adriatic with the Yugoslavian Navy, naval history, and more current naval operations. His book is a comprehensive examination of littoral warfare for the student or practitioner and covers everything from the space and geometries of the littoral to sea denial and relevant weapons systems. It is a perfect book to use both as an introduction and a deeper dive into littoral warfare. However, originally published in 1999, Vego’s book has not been updated to reflect geopolitical and technological changes.

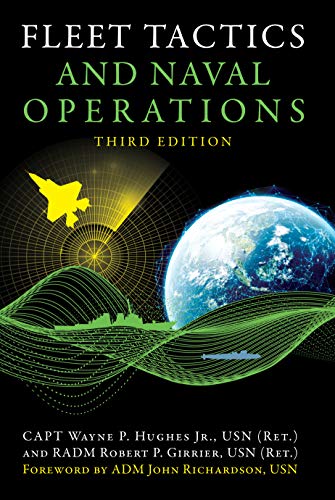

Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, Third Ed. by Captain Wayne P. Hughes (ret.) and Rear Admiral Robert P. Girrier (ret.)

Hughes, a recently passed professor at the Naval Postgraduate School and former U.S. Navy officer, was a giant in the study of naval tactics. The third edition of Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat is similar to Naval Strategy and Operations in Narrow Seas in that it breaks down and explains warfare in the littoral. The book also explains Hughes’ salvo model for missile combat, which is the standard for modeling missile combat at sea, and provides an excellent starting point from which Marines can begin to factor their shore-and air-based fires into the maritime fight. The book is an A-Z explanation of littoral warfare and also looks forward into continuing trends and the future of littoral warfare. The most recent edition, co-authored by Rear Admiral Robert P. Girrier, and with a forward written by then-Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson, includes a chapter discussing current revolutions in military affairs and a fictional scenario depicting how a modern war in the littorals could feasibly unfold.

Hughes, a recently passed professor at the Naval Postgraduate School and former U.S. Navy officer, was a giant in the study of naval tactics. The third edition of Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat is similar to Naval Strategy and Operations in Narrow Seas in that it breaks down and explains warfare in the littoral. The book also explains Hughes’ salvo model for missile combat, which is the standard for modeling missile combat at sea, and provides an excellent starting point from which Marines can begin to factor their shore-and air-based fires into the maritime fight. The book is an A-Z explanation of littoral warfare and also looks forward into continuing trends and the future of littoral warfare. The most recent edition, co-authored by Rear Admiral Robert P. Girrier, and with a forward written by then-Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson, includes a chapter discussing current revolutions in military affairs and a fictional scenario depicting how a modern war in the littorals could feasibly unfold.

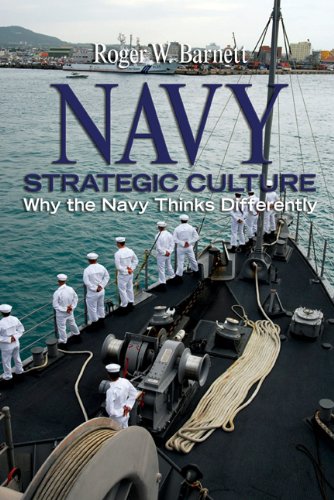

Navy Strategic Culture: Why the Navy Thinks Differently by Roger W. Barnett

Navy Strategic Culture is an important book because it dissects what makes the Navy different from the other services and critically, why that matters. Barnett is another former U.S. naval officer and instructor at the U.S. Naval War College. His book can either be a jumping-off point for a reader who wants to better understand the Navy and does not know where to start, or for a reader who has experienced the Navy firsthand and wants to understand why the Navy is unique. The book will provide the reader with both a better understanding and a better appreciation for the U.S. Navy and its contribution to U.S. strategy writ large.

Navy Strategic Culture is an important book because it dissects what makes the Navy different from the other services and critically, why that matters. Barnett is another former U.S. naval officer and instructor at the U.S. Naval War College. His book can either be a jumping-off point for a reader who wants to better understand the Navy and does not know where to start, or for a reader who has experienced the Navy firsthand and wants to understand why the Navy is unique. The book will provide the reader with both a better understanding and a better appreciation for the U.S. Navy and its contribution to U.S. strategy writ large.

Learning War: The Evolution of Fighting Doctrine in the U.S. Navy, 1898–1945 by Trent Hone

Whenever young naval officers ask for book recommendations from senior commanders, this book is almost guaranteed to be on the list. Learning War assesses the generations of work and force development that was done in the years leading up to the Second World War that transformed the U.S. Navy into an organization that can adapt to and excel against emerging great power threats. The book, a favorite of CNO Richardson’s, shows how even after several bruising defeats early in the war the U.S. Navy still needed time to adapt and evolve. In future conflicts, critical events could very well be decided on a far shorter timeframe, begging the question as to whether our current learning culture as a military service is going to be up to the challenge in a future war that might only last months as opposed to years.

Whenever young naval officers ask for book recommendations from senior commanders, this book is almost guaranteed to be on the list. Learning War assesses the generations of work and force development that was done in the years leading up to the Second World War that transformed the U.S. Navy into an organization that can adapt to and excel against emerging great power threats. The book, a favorite of CNO Richardson’s, shows how even after several bruising defeats early in the war the U.S. Navy still needed time to adapt and evolve. In future conflicts, critical events could very well be decided on a far shorter timeframe, begging the question as to whether our current learning culture as a military service is going to be up to the challenge in a future war that might only last months as opposed to years.

The Price of Admiralty: The Evolution of Naval Warfare by John Keegan

John Keegan is an award-winning British historian and former lecturer at Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. The Price of Admiralty is his attempt to write about naval history, as Keegan is, in the words of a critical review by Wayne Hughes, a “landlubber.” He has researched and written extensively on ground combat, however he can still deliver in his explanations and descriptions of naval combat. The Price of Admiralty is as exhaustively researched as his other books and presents an accessible and valuable history of naval warfare from the perspectives of the combatants. Though British-centric, The Price of Admiralty can provide any reader with a better understanding of what naval combat is, how it feels, and how it has evolved over the centuries.

John Keegan is an award-winning British historian and former lecturer at Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. The Price of Admiralty is his attempt to write about naval history, as Keegan is, in the words of a critical review by Wayne Hughes, a “landlubber.” He has researched and written extensively on ground combat, however he can still deliver in his explanations and descriptions of naval combat. The Price of Admiralty is as exhaustively researched as his other books and presents an accessible and valuable history of naval warfare from the perspectives of the combatants. Though British-centric, The Price of Admiralty can provide any reader with a better understanding of what naval combat is, how it feels, and how it has evolved over the centuries.

Small Boats and Daring Men: Maritime Raiding, Irregular Warfare and the Early American Navy by Benjamin Armstrong

The core argument in Armstrong’s new book Small Boats and Daring Men is that irregular warfare at sea was critical to the success of the early American navy, and was quite common. Armstrong, a history professor at the United States Naval Academy, mixes well-known cases of irregular warfare, like those conducted against the Barbary Pirates, with lesser known but equally interesting cases like the U.S. naval expeditions to Sumatra. Small Boats and Daring Men is a fascinating study of 18th and 19th century maritime competition and conflict that may change the reader’s perspective on the age of sail and the history of the U.S. Navy. It also offers a historical basis for irregular littoral operations.

The core argument in Armstrong’s new book Small Boats and Daring Men is that irregular warfare at sea was critical to the success of the early American navy, and was quite common. Armstrong, a history professor at the United States Naval Academy, mixes well-known cases of irregular warfare, like those conducted against the Barbary Pirates, with lesser known but equally interesting cases like the U.S. naval expeditions to Sumatra. Small Boats and Daring Men is a fascinating study of 18th and 19th century maritime competition and conflict that may change the reader’s perspective on the age of sail and the history of the U.S. Navy. It also offers a historical basis for irregular littoral operations.

Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal by James D. Hornfischer

The Marine Corps solemnly remembers the 1,592 Marines killed during the Guadalcanal campaign and the horrific fighting that ensued there. It is also quick to recall that the first month of the campaign was conducted largely without the support of naval forces, which were intended to support the troops on the ground. What is often forgotten is that during the operation U.S. and Japanese naval forces were relatively similar in strength, that the outcome of the battle at sea was far from certain, and a naval defeat would spell certain defeat on land. Hornfischer, with several other award-winning books about the U.S. Navy to his name, is well-versed in applying narrative history to naval storytelling. His work here provides ready and digestible insights into how naval- and land-based objectives became intertwined at the tactical and operational level of war and, in doing so, he gives the reader a critical retelling of this pivotal littoral battle so familiar to Marines, from the naval perspective.

The Marine Corps solemnly remembers the 1,592 Marines killed during the Guadalcanal campaign and the horrific fighting that ensued there. It is also quick to recall that the first month of the campaign was conducted largely without the support of naval forces, which were intended to support the troops on the ground. What is often forgotten is that during the operation U.S. and Japanese naval forces were relatively similar in strength, that the outcome of the battle at sea was far from certain, and a naval defeat would spell certain defeat on land. Hornfischer, with several other award-winning books about the U.S. Navy to his name, is well-versed in applying narrative history to naval storytelling. His work here provides ready and digestible insights into how naval- and land-based objectives became intertwined at the tactical and operational level of war and, in doing so, he gives the reader a critical retelling of this pivotal littoral battle so familiar to Marines, from the naval perspective.

There are several other outstanding histories of the Solomons Campaign and Guadalcanal that are worthy mentions, including Ian W. Toll’s Pacific Crucible, Joseph Wheelan’s Midnight in the Pacific, and Richard B. Frank’s Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account.

One Hundred Days: The Memoirs of the Falklands Battle Group Commander by Patrick Robinson and Sandy Woodward

The Falklands War is the best case of a “modern” amphibious battle. Fought over islands in the South Atlantic between the United Kingdom and Argentina, the Falklands campaign is frequently referred to as a case study on how modern naval combat works. Much of the weaponry and tactics used in the Falklands are still standard today, and the war saw joint forces on both sides fighting maritime campaigns, including amphibious operations. The reader can learn many lessons from Woodward – the British task force commander. His memoir is frank and he candidly discusses his successes and mistakes. A careful reader would also do well to note the changes in naval warfare and the operating environment over the last four decades so as to not get caught in the trap of fighting the last war.

The Falklands War is the best case of a “modern” amphibious battle. Fought over islands in the South Atlantic between the United Kingdom and Argentina, the Falklands campaign is frequently referred to as a case study on how modern naval combat works. Much of the weaponry and tactics used in the Falklands are still standard today, and the war saw joint forces on both sides fighting maritime campaigns, including amphibious operations. The reader can learn many lessons from Woodward – the British task force commander. His memoir is frank and he candidly discusses his successes and mistakes. A careful reader would also do well to note the changes in naval warfare and the operating environment over the last four decades so as to not get caught in the trap of fighting the last war.

There are several other worthwhile studies of the Falklands War including The Official History of the Falklands Campaign by Sir Lawrence Freedman, a professor at King’s College in London, and Battle for the Falklands by journalists Max Hastings and Simon Jenkins.

Red Star Over The Pacific: China’s Rise and the Challenge to U.S. Maritime Strategy, Second Ed. by Toshi Yoshihara and James R. Holmes

In Red Star Over The Pacific, Holmes and Yoshihara provide a much-needed update to their original 2013 edition. Yoshihara and Holmes are China and maritime strategy experts – Holmes is currently the J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the U.S. Naval War College, and Yoshihara formerly held the John A. van Beuren Chair of Asia-Pacific Studies at the Naval War College and is now a senior fellow at CSBA. Their book outlines the massive growth in capability and size of China’s naval forces in a way that is straightforward to understand, and they also cover the implications of Chinese naval force development and the way it impacts and compares to the U.S. Navy. Fascinating and current, the book is also a warning to the reader to take competition and potential conflict in the Pacific seriously, as the authors make clear just how important naval power has become to Chinese grand strategy.

In Red Star Over The Pacific, Holmes and Yoshihara provide a much-needed update to their original 2013 edition. Yoshihara and Holmes are China and maritime strategy experts – Holmes is currently the J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the U.S. Naval War College, and Yoshihara formerly held the John A. van Beuren Chair of Asia-Pacific Studies at the Naval War College and is now a senior fellow at CSBA. Their book outlines the massive growth in capability and size of China’s naval forces in a way that is straightforward to understand, and they also cover the implications of Chinese naval force development and the way it impacts and compares to the U.S. Navy. Fascinating and current, the book is also a warning to the reader to take competition and potential conflict in the Pacific seriously, as the authors make clear just how important naval power has become to Chinese grand strategy.

The War for Muddy Waters: Pirates, Terrorists, Traffickers and Maritime Security by Joshua Tallis

Tallis’s new book is easily among the most current on this list. What Tallis argues in The War for Muddy Waters is that maritime security is as important and will continue to be as important as traditional naval warfare. Tallis dives into security issues in the littoral with pirates, smugglers, and terrorists and presents a view of maritime security challenges that is often overlooked but increasingly important as demographics shift toward ever more littoralization. The War for Muddy Waters will expose the reader to the broader but equally relevant world of maritime security beyond limited naval issues.

Tallis’s new book is easily among the most current on this list. What Tallis argues in The War for Muddy Waters is that maritime security is as important and will continue to be as important as traditional naval warfare. Tallis dives into security issues in the littoral with pirates, smugglers, and terrorists and presents a view of maritime security challenges that is often overlooked but increasingly important as demographics shift toward ever more littoralization. The War for Muddy Waters will expose the reader to the broader but equally relevant world of maritime security beyond limited naval issues.

Front Burner: Al Qaeda’s Attack on USS Cole by Kirk Lippold is an excellent anti-terrorism and force protection case study that expands on the irregular threat to warships and the Navy in port and in the littoral. Another great and recent book on non-naval maritime issues is journalist Ian Urbina’s The Outlaw Ocean: Journeys Across the Last Untamed Frontier.

Beans, Bullets, and Black Oil by Worrall R. Carter

If General Omar Bradley was correct in his alleged quip that “Amateurs talk strategy, professionals talk logistics,” there is no better place to begin the discussion of naval logistics than with Beans, Bullets, and Black Oil. Carter details the logistics efforts of the U.S. Navy in the Pacific theater during the Second World War. The book covers many facets of modern naval logistics including expeditionary logistics, forward basing and sea basing, maintenance, and supply activities inside in contested areas. Many of the logistics fundamentals the Navy dealt with in the Second World War still apply today. If nothing else, the book is sure to give Marines and sailors alike a far greater appreciation of the immense logistical effort required to sustain maritime campaigns across an area as large as the Pacific.

If General Omar Bradley was correct in his alleged quip that “Amateurs talk strategy, professionals talk logistics,” there is no better place to begin the discussion of naval logistics than with Beans, Bullets, and Black Oil. Carter details the logistics efforts of the U.S. Navy in the Pacific theater during the Second World War. The book covers many facets of modern naval logistics including expeditionary logistics, forward basing and sea basing, maintenance, and supply activities inside in contested areas. Many of the logistics fundamentals the Navy dealt with in the Second World War still apply today. If nothing else, the book is sure to give Marines and sailors alike a far greater appreciation of the immense logistical effort required to sustain maritime campaigns across an area as large as the Pacific.

Periodicals

We would also like to emphasize the great periodical publishing on naval and maritime security issues. Proceedings is a professional publication of the United States Naval Institute, and it publishes a monthly issue with articles on a range of issues relevant to the Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard online and in print. It also features regular essay contests on a variety of topics.

The U.S. Naval War College publishes the Naval War College Review quarterly but also has a variety of longer-form manuscripts and working papers. Because it is a government-funded entity, all War College publications are free to download from their website.

Lastly, the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC) publishes a range of content on a near-daily basis related to maritime security, all of it fully available to read for free on their website. CIMSEC is U.S. based, but not U.S. centric – which makes for a more international perspective. They also release regular calls for submissions on specific topics.

Conclusion

We believe that these books and publications are an excellent jumping-off point for any landlubber looking to learn more about naval and maritime perspectives, but especially for Marines who recognize that these perspectives have been missing from their professional military education. This is by no means an exclusive list – there are dozens if not hundreds of more fantastic books out there. These are just our personal recommendations and books that have been important in our own learning. More books on naval integration may be in the making, and certainly many have already been published that cover the Navy-Marine relationship, just waiting to be discovered and shared.

Happy reading.

Walker D. Mills is a Marine infantry officer currently serving as an exchange officer in Cartagena, Colombia. He has previously authored commentary for CIMSEC, the Marine Corps Gazette, Proceedings, West Point’s Modern War Institute and War on the Rocks. He is an associate editor at CIMSEC. He can be found on twitter @WDMills1992.

Joseph E. Hanacek is a Surface Warfare Officer stationed in San Diego, CA. He has served aboard USS Lake Champlain (CG-57) and USS Jackson (LCS 6), and recently graduated from the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, CA. He has previously authored commentary for Proceedings and War on the Rocks.

Featured Image: A Marine puts away returned books in the library aboard USS Bataan (LHD 5). (Mass Communication Specialist Seaman Apprentice Aaron T. Kiser/Navy)