By LCDR Reuben Keith Green, USN (ret.)

Introduction

The Navy has always had the same three problems when it comes to diversity and inclusion. The first is that there is racism in the ranks. This is America, so that is to be expected. The second is a failure of leadership. No less an individual than the current Secretary of the Navy has pointed out to Congress and the press that failure of leadership in the Navy is a problem today. The third is an unwillingness to face head-on the first two problems. To do so would require some deep introspection, radical change, and likely adverse publicity as the dirty laundry gets aired, which every organization hates.

An active duty Black sailor wrote a review of my memoir on July 26, 2020, which said, “As a Black American Sailor, this book confirmed a lot of what I (in 2020) personally have experienced in my career thus far. The names and faces may have changed, but the traditions of old remained. This book brought me to tears. I am better for reading this, but dejected at the realization that much will not change in the Navy.” The recent articles written in USNI Proceedings’ blog and magazine detail the thoughts and experiences of active duty officers who have faced discrimination. These individuals echo the same sentiments that my sailor father shared with me 50 years ago when he forbade me to join the Navy.

I have been worried about the Navy’s race problem since I was ten years old. I listened to my father’s and his friends’ inappropriate sea stories, and read encyclopedias that hid the truth from me while dreaming of being a naval officer. But there weren’t any Black naval officers in the encyclopedias, or the sea stories. I knew that there were stories I shouldn’t be hearing and that the ones I should have been reading were missing. It wasn’t until my parents bought books on the Black experience in the American experiment that the truth began to be revealed to me. Today at the age of 63, I am more worried now than I have been in a long time. So is the Department of Defense. That means you should be worried, too.

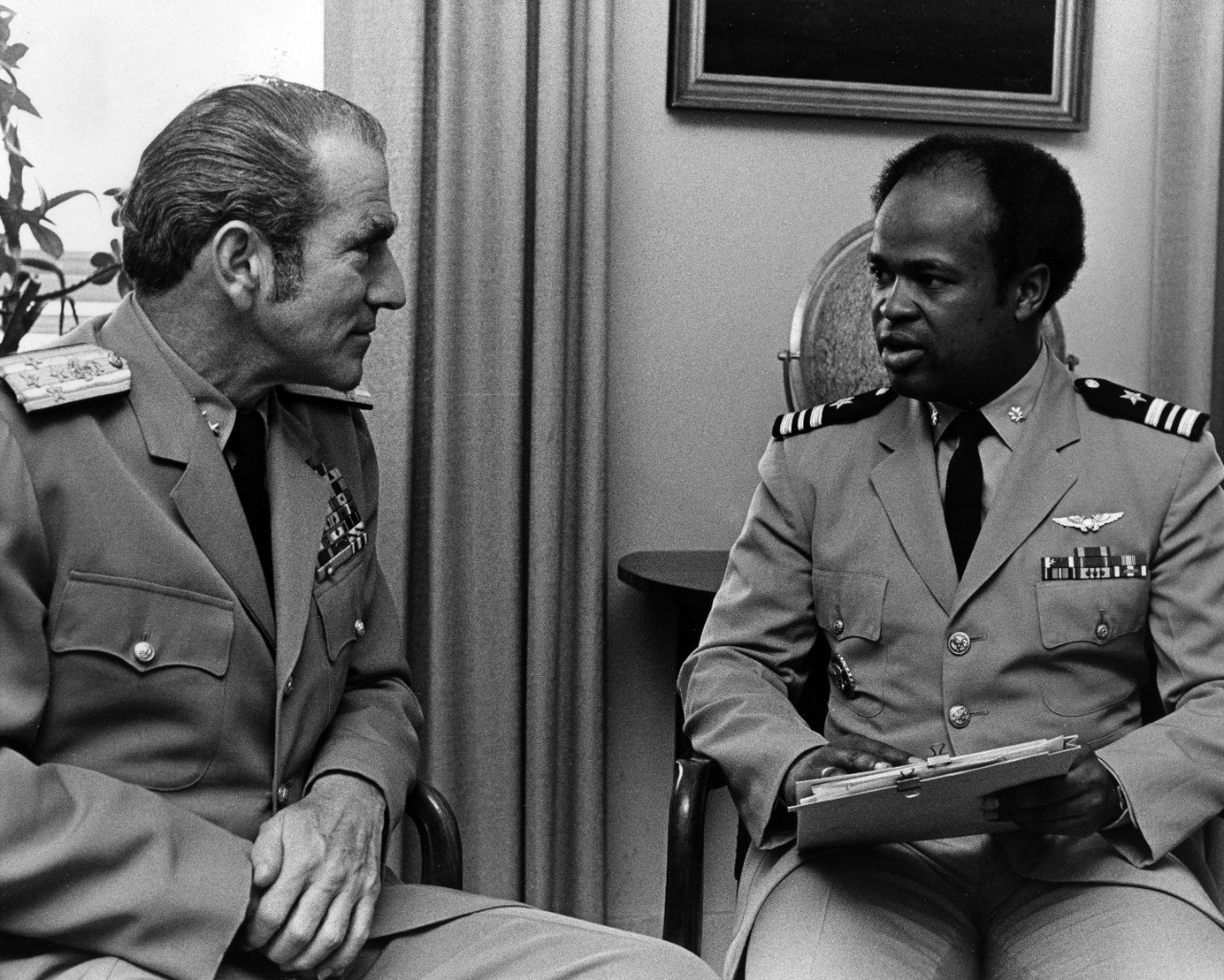

So, what to do? I can tell you that the current fad of listening to sailors and officers is not going to be nearly enough. The Navy and the military is at a point where radical change, such as was attempted by Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Elmo R. Zumwalt during his tenure, is clearly necessary, even essential. It will be painful.

Understanding Culture

The Navy doesn’t need another task force, study group, commission, or detailed directive to minimize discrimination and sexual assault/harassment in the ranks. Those are stacked a mile high, unread and unheeded. The last time I checked, the Navy had done more of those than any other service, and for good reason – but to little effect. What the Navy needs to do is to hold commanders and leaders responsible and accountable in the same way it holds them accountable if they are involved in a collision at sea or a vessel grounding. What the Navy needs to do is to target the problem as though it were an operational necessity and matter of national security to fix, because it is.

I think the Navy understands that, but is unclear on how to fix it – or unwilling to do what is required. One thing missing in the Navy’s approach is assigning culpability for discrimination and racism. If no one is culpable, then there is no one that can or will be held responsible.

A ship damaged at sea or run aground, or with a physically degraded crew, clearly impacts the operational readiness of that ship. A ship or command whose crew is mentally impacted in unit cohesiveness, mistrust, discrimination, mental cruelty, lack of personal security and morale, will experience degradations which are just as dangerous to the functioning of the organization. People who don’t trust or who abuse each other have difficulty working together effectively, which is the very essence of an elite team. The difference in these two problems is the accountability factor, or lack thereof.

The USS Shiloh “Prison Ship” debacle of a few years ago is instructive. The Shiloh skipper exhibited anti-diversity behavior and comments, doled out extremely harsh punishments for minor offenses (three days bread and water), and was obsessed with obtaining his favorite personal beverage, at the expense of more pressing crew and operational concerns. His behavior was deemed racist by some of the crew. The Navy was well aware of the problems aboard the ship, having increased the frequency of the command climate surveys, which steadily deteriorated, and repeatedly “counseled” the captain of the ship. Despite the written pleas of the officers and crew, which grew more desperate, and the well-known waterfront reputation of the ship, the Navy did not act. Instead, the captain transferred ashore with his head held high and a shiny new end of tour medal, while the psychological devastation to some of his crew began to have what is likely lasting effects on many individuals. Once the stories made the news, it was too late to effectively ameliorate the damage done to the individuals. And still, the Navy stood by the skipper, because “the ship performed well operationally.” Not only was the captain not held accountable, he was rewarded. Officially, his judgement was not found lacking until a subsequent inspector general investigation was conducted.

Contrast that with the case of Captain Brett Crozier, formerly captain of the USS Theodore Roosevelt. By all accounts he was an outstanding skipper, and had a reputation for being a caring commander, which apparently contributed to his downfall. In the midst of a pandemic, which severely impacted both the health of his crew and the operational capability of the ship, he wrote a memo requesting guidance and help that was subsequently leaked to the press. He was relieved for “poor judgement.” Despite a lack of a clear management strategy, little specific guidance, conflict with his embarked commander, and an exponentially increasing casualty list, he was summarily relieved by an individual who infamously displayed far worse judgement himself. Following the uproar, a subsequent investigation was ordered and conducted, and the finding was the same – poor judgement. I take issue with the findings and recommendations of the investigation, as does an expert on naval investigations, Captain Michael Junge, who wrote the bible on the subject, Crimes of Command in the United States Navy. His precise critique of the investigation, as well as his book, should be required reading for all naval officers. His thoughts on accountability, responsibility, and culpability are as relevant to this discussion as they are to the discrimination and sexual harassment/assault issues currently in focus.

Ask yourself, who did more damage to the Navy, Captain Crozier, or the skipper of the Shiloh? Further, ask yourself who was held culpable and who was not. Ask yourself if the treatment of Captain Crozier sent the right message to officers trying to lead under difficult and unprecedented circumstances.

To my knowledge, no formal Navy investigation was conducted into the Shiloh affair, even as the Navy received bad press and piercing questions from around the world until well after the captain was relieved on schedule. An investigation should have been conducted while he was in command, and the skipper should have been held to account. Failure to do so sent a terrible signal throughout the fleet, echoes of which can be heard in the fallout from the Theodore Roosevelt incident. Caring too much about the welfare of your crew can get you fired; driving them to mental instability and psychological exhaustion, while making jokes about it, can get you rewarded. The Navy seemed to be willing to reward a commander who ignored or prevented efforts to honor the diverse heritage and contributions of minority sailors and develop a unity mindset, throwing 50 years of precedent down the drain.

In the 50 years I have been studying this issue, I can only recall one incident where an officer has been held to account for racist language and behavior. This flag officer was relieved for making derogatory comments regarding Black officers, including those superior to him, and making racially offensive comments and gestures while in command. I only know this because another fine carrier skipper took issue with his behavior and reported it to the proper authorities. The facts that the carrier skipper was an unimpeachable witness, and that others witnessed the comments and behavior, are significant. Most people who report such offenses do not have these advantages, and I speak from hard experience. This case was a clear exception to the rule.

For decades the Navy has downplayed or dismissed overwhelmingly formal discrimination complaints submitted by sailors and officers. This has to change. There are federal lawsuits pending right now stemming from racial discrimination in naval aviation, and the case of former Lieutenant Courtland Savage is exhibit A. He recently wrote about his experiences and frustration in Travel World Magazine, and his story was reported in Military Times and elsewhere a few years ago. The Navy acknowledged “ethnic insensitivity” but no discrimination.

I beg to differ. I wrote a letter expressing my concerns, which was passed to the DoD Inspector General handling the case. A white Navy lieutenant, who spoke up and acknowledged the discrimination, is now involved in a federal lawsuit, where he is fighting the retaliatory actions taken against him for speaking out. This type of retaliation is as predictable as the sunrise. Retaliation is the number one concern of individuals who report discrimination in the military, and for very good reason. This case needs transparency.

The Navy needs to demonstrate the same commitment to eradicating these longstanding and seemingly intractable discrimination and harassment issues as they demonstrated in stamping out the rampant and widespread abuse of illegal drugs during the 70s and 80s. I recall that the day I graduated from the legal clerk course at Naval Justice School in Newport in 1977, some of my senior fellow graduates celebrated graduation by smoking a joint in the barracks while packing up their belongings. I was an E-4, and this didn’t surprise me. As a Legal Yeoman, I processed many drug offenders, counseled many sailors as a substance abuse prevention practitioner, and held people accountable as a division officer aboard ship.

Following some significant incidents aboard ship in which illegal drug use possibly contributed to property damage and injuries, and diminished operability, the Navy cracked down hard and helped turn this around. Officers were held to the highest standard, as it should be. There was a top down, fleet-wide commitment to ending drug abuse, with clear punishments, rehabilitation, and possibilities for redemption.

It worked. It can work for this current crisis as well, with proper commitment and leadership. The “zero tolerance” stance for officers who abused drugs should be adapted for officers who abuse people.

Let’s return to the issue of commissions, study groups, and reports. In the June 1990 issue of All Hands Magazine, there was an eight-page article on the state of race relations in the Navy. Then-Chief of Naval Personnel Admiral Jeremy “Mike” Boorda referred to the Chief of Naval Operations Study Group’s Report on Equal Opportunity, published in 1988. The report had indicated that there was widespread bias and discrimination against Blacks in the Navy. Boorda said that the programs in place had “realized major improvements in recent years.” A few years later, in 1996, he unfortunately took his own life while still serving as the Chief of Naval Operations, and while fighting for change to the culture.

He was fighting for people like me. Five days before his death, I filed a request for redress against a racist and abusive commanding officer who was being protected by a racist and abusive immediate superior in command, for whom I had worked in the 90 days before he fleeted up to his next command. Rather than cause the Navy any further bad press, and because my complaint was illegally withheld in violation of the governing directives, I chose to quietly retire, understanding that no effort would be spared to discredit and destroy me should I push the issue to an appropriate and legal resolution.

I have never seen the report, but I am confident that it addresses many of the same problems that exist today. These problems are not new, they are perpetual. I know because they have existed for my entire lifetime. What has to be new is the approach to solving them.

Admiral Zumwalt got the Navy off to a great start, but the civilian and naval leadership failed him, and the country. His nemesis, Mississippi Senator John C. Stennis, and his superior officer, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Admiral Thomas Moorer, a racist, did much to undermine Zumwalt’s efforts. The active duty and retired military leadership never got behind Zumwalt’s efforts. Zumwalt recalled in his memoir that Moorer opposed his selection as Chief of Naval Operations and accused him of “blackening his Navy,” and the post-retirement television debate he had with Zumwalt did not reflect well on Admiral Moorer and his position on race. Zumwalt’s successor, Admiral James Holloway III, said Zumwalt had “went too far.”

The Boogaloo Boys, a white supremacist group, contains many active duty and veteran service members, as do other racist and radical groups. I am looking askance at my beloved Hawaiian shirts as I write. Symbology is important. If the price for removing Confederate flags from military bases is giving up my shirts, I’ll make the sacrifice. While the overt racism is troubling, the more insidious, hidden racism likely does more damage in the long run. The outcry over the recently outed retired naval academy alumnus who accidentally livestreamed racist comments on Facebook ignores the fact that he spent 30 years in the Navy, as his hidden racism was masked (or was it ignored, or worse, accepted?) as he likely negatively impacted the careers of numerous minority officers and sailors. Did he ever sit on a promotion or selection board? Has anyone examined his history of fitness reports and evaluations? Implicit bias does damage daily, and simply changing the rules on photographs for selection boards is like giving someone who has COVID-19 some aspirin and putting them on bedrest – treating the symptoms, not the cause.

I recently tangled with a retired Navy captain who called me a racist on LinkedIn because he didn’t like the title of my book, Black Officer, White Navy, and also inferred that minority officers received “special treatment” at selections boards because of the color of their skin. He subsequently deleted his racist comments, and my responses to them, but I saved the screenshots, as a reminder of just how pervasive these attitudes are.

The officers who have spoken publicly (in writing) about the discrimination they have faced have been met with hostility, racism, denial, derision, and ridicule, judging from the comments on the recent USNI articles written by Lieutenant Commander Desmond Walker and Commander Jada Johnson. Similar comments have been made regarding the banning of divisive symbology from military installations. Of particular dismay is the fact that many of the comments outright deny the existence of institutional racism. One poster goes so far as to say that the current efforts to end racism and discrimination will only make things worse, while flatly denying that institutional racism is even a real thing. This white backlash is as old as the Navy’s efforts to end systemic racism dating to the Zumwalt era, and the arguments are largely the same. Given the public response, it is not difficult to imagine the private conversations.

Conclusion

The Chief of Naval Operations has acknowledged that there is racism in the Navy. He needs to go one natural – but painful – step further and acknowledge that you can’t have racism without racists. You can’t have rape without rapists. You can’t have sexual harassment without harassers. You can’t have discrimination without actions, both individual and institutional, that discriminate. You can’t have failed leadership without failed leaders.

If the Secretary of the Navy is right, and naval leadership is lacking, then this is a good place to start. It will pay dividends for decades to come if Navy leadership, led by Admiral Gilday, takes charge and leads from the front. Given the other challenges that have arisen since his June 2020 initiative, I am concerned that this effort will slip to the backburner, and become yet another in a series of failed efforts to minimize discrimination in the fleet. That would add to the dejection, as stated by the sailor mentioned above, that permeates the Navy. It would be a devastating failure to have raised hopes for change to then see them dashed due to other concerns. At some point, as has been demonstrated in the past, the relief valve will pop.

I was a young division officer with ten years in the Navy when Admiral Gilday graduated from the Naval Academy in 1985. I imagine he thinks he knows how bad it is, but he can’t. He can imagine it, but he will fall woefully short. He has the right idea, but he needs help from those with direct experience and a willingness to speak truth to power, always a risky venture. Unless he finds himself a young Black naval officer, or other minority personnel, assigned to his staff to advise him, he still won’t truly get it. He needs a William S. Norman, Zumwalt’s minority affairs assistant, who methodically educated Admiral Zumwalt to the point of trauma on the experiences of Black sailors and officers in the Navy. He needs to read the comments directed at the officers who have spoken out, and at me. The misrepresentations and reductionist dismissals are stunning. Naval officers Desmond Walker and Jada Johnson, who bravely shared their experiences and recommendations in Proceedings, are the type of officers I have in mind.

The old lions, the Black retired naval flag community, are very quiet, when they should be roaring and sharing their stories. While some offer tepid congratulations for the changes in the Coast Guard and Navy to senior officers, they are apparently missing the reality on the deckplate, or sharing their concerns more privately. Retired Master Chief Melvin Williams, the father of Vice Admiral Melvin Williams, should get a personal invitation to share his perspective, having written a book with his son that describes their experiences with discrimination and leadership. According to Melvin G. Williams Sr., in a review of my own book, “His story was so unusual and so disturbing in its recapping of events that even an old Navy veteran such as me had to hold back tears…His story provides many lessons to be learned and guidelines to be followed. Those who run the Navy should consider this book a gift.”

Air Force Chief of Staff General Brown’s electrifying personal testimony struck a chord with me, and many others. He roared, quietly but publicly, and with dignity. Now he’s taking action with resolve and commitment. Despite his best intentions, Admiral Gilday likely doesn’t have a similar understanding of the problem compared to General Brown. He needs a Black man or woman to explain it to him. I’m sure he has General Brown’s number. They should have lunch, and invite William S. Norman and Master Chief Melvin Williams along for good measure. Old lions have the most scars, and the most wisdom. They should have lunch in the wardroom of the USS John C. Stennis. It will be messy and uncomfortable, but informative, to look at the pictures on the wall and the faces of the Sailors serving them in the wardroom. Or better said, the faces of the Sailors they serve.

CNO, pull up a chair and chat with an old Black Sailor. I can tell you that having a former sailor ridicule you in print and refuse to acknowledge even the existence of institutional discrimination is unsettling. Having that same individual delight in “making me insane” by refusing to do so, and treat other minority active duty officers the same way (from anonymity, he thinks) reveals the underlying objective, which is to cause further pain. Having to work alongside that sort of individual is something I am quite familiar with. The scars are lasting. The high disability rating for Black veterans is not an accident, it is a predictable outcome.

Our sailors have suffered enough. CNO, to paraphrase Sean Connery in the movie The Untouchables, “What are you going to do?”

Reuben Keith Green is a retired surface warfare officer who served for 22 years in the Atlantic Fleet (1975-1997). A former mineman, legal yeoman, Equal Opportunity Program Specialist, administrative office leading petty officer, and leadership instructor, he served four consecutive sea tours upon his commissioning via Officer Candidate School in 1984. He qualified as both a steam and gas turbine engineer officer of the watch (EOOW), Tactical Action Officer (TAO) in the Persian Gulf, and served as executive officer in a Navy hydrofoil, USS Gemini (PHM-6). He graduated from the Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute in 1980.

Featured Image: Senior Chief Electronics Technician Darrick L. Terry, a Recruit Division Commander from Rockinhham, North Carolina assigned to Officer Training Command Newport (OTCN) in Rhode Island, corrects the salutation performed by a student with Officer Development School (ODS) class 2020, Feb. 6. (U.S. Navy photo by Darwin Lam)