By Bill Bray

I grew up in white neighborhoods and my Catholic high school outside Boston was entirely white. I never knew a black community. If racism still existed, it existed elsewhere. It was an abstraction to me. Then I joined the Navy. In the summer of 1983, while at the Naval Academy Prep School in Newport, Rhode Island, my roommate was a black man from the South Side of Chicago. He did not last long—a week, maybe ten days—before he quit. I cannot remember his name. But what I can remember, all too clearly, was that while we may have been from the same country and in the same Navy, we might as well have been from different planets.

In looking back on my nearly three-decade Navy career beginning in the late 1980s, I see now even more clearly how racial bias among a mostly white officer corps was far more ingrained and consequential than I believed—or cared to believe. Much work has and is being done about this, but here is one observation, based on my experience as an officer and an editor, that is rarely discussed or written about: white officers generally do not read black writers (and if they read much literature at all, it consists of other genres). They should, and a good place to start is with James Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain.

Reading good literature begets many benefits. The best writers are experts on the human condition, and reading them enlarges and enriches self-awareness, humility, and empathy. A growing body of social science research supports this assessment. For example, in 2013 researchers Emanuele Castano and David Comer Kidd published in the journal Science the results of a study that concluded reading literary fiction, as opposed to serious nonfiction or plot-driven popular fiction, enables people to score better on tests measuring empathy, social perception, and emotional intelligence. In an interview with The New York Times, Castano notes that in literary fiction, such as Dostoyevsky, “there is no single, overarching authorial voice…each character presents a different version of reality, and they aren’t necessarily reliable. You have to participate as a reader in this dialectic, which is really something you have to do in real life.”

James Baldwin is one of the most important American writers of the twentieth century. His writing is excellent and his personal journey compelling. Go Tell It on the Mountain is his first novel. It took him ten years to write and he struggled mightily with doubt that he could ever finish it. It is semiautobiographical and centers on his tormented relationship with his stepfather and the deeply religious community to which they belonged.

Born in 1924, Baldwin grew up in Harlem. His family was originally from the South and part of the great northward migration of approximately six million African Americans as Jim Crow laws in the South stiffened. While working on the book, Baldwin left the United States to live in Paris. He finished it in 1952 while living in the Swiss village of Loeche-les-Bains. In Europe, where he did not have to be reminded on a daily basis of the deep-seated racism in America, he was finally able to finish a book that was also a painful process of discovering who he was. As the writer Edwidge Danticat explained in a 2016 article in The New Yorker:

“In a 1961 interview with the American broadcaster and oral historian Studs Terkel, Baldwin remembered thinking that he might never finish the novel. . . ‘I was ashamed of the life of the Negro church,’ he told Terkel, ‘ashamed of my father, ashamed of the Blues, ashamed of Jazz, and, of course, ashamed of watermelon: all of those stereotypes that the country inflicts on Negroes, that we all eat watermelon or we all do nothing but sing the Blues. Well, I was afraid of all that; and I ran from it.’”

Many American writers became expatriates to seek out new ideas and cultures. Not as many left because they were ashamed of how their own are commonly viewed in their native country.

The novel centers around a single day in the life of John Grimes (the autobiographical character) on his 14th birthday. The Negro church in the novel is the Temple of the Fire Baptized Church, a Pentecostal congregation that operates from a Harlem storefront—“It was not the biggest church in Harlem, nor yet the smallest, but John had been brought up to believe it was the holiest and best.”

The day begins when John wakes, convinced his mother has forgotten his birthday. She has not, although she makes no mention of his birthday all morning. Later, after he completes his chores, she gives him money to explore the city. He ventures into Manhattan, where we get a sense of his anger and loneliness at being a black teenager in mid-1930s New York, and ends the day at a church service with his mother, stepfather, the young preacher Elisha, and others, where he undergoes a violent and tumultuous conversion on the “threshing-floor” (Baldwin himself was a preacher from ages 14–17).

Along the way in the book, we are taken back in time through the stories of his Aunt Florence, Florence’s brother, and John’s stepfather Gabriel Grimes, and his mother Elizabeth. Their stories mostly predate the migration north, and we see them as complex, sinful characters, who are both victims of grievous injustices and of their own poor decisions and fallibility. Scene after scene drips with an intense religiosity and pathos of a people struggling to survive their environment and themselves. Gradually, through their stories (each of the three chapters in part two is titled a prayer), we interact with a host of other characters that come in and out of their lives.

John Grimes never knows many of these characters, has never been to the South, and could not possibly know most of the intricate details. But Baldwin wants us to know and to feel that they are all part of who he is (and who Baldwin is). Following the scenes of John Grimes in New York City that day, we then experience a complex labyrinth of stories of his family from years ago—the story of the wider African American experience from Reconstruction onward—until we are brought rushing back to the boy in the all-night church service. It is as if his entire identity is carefully and intricately revealed to us through the lives of the others. Each experience they have and each choice they have made matters to who John Grimes is.

In a 1984 Paris Review interview, Baldwin credited Henry James for how he told and structured the story. “Henry James helped me, with his whole idea about the center of consciousness and using a single intelligence to tell the story. He gave me the idea to make the novel happen on John’s birthday.” Baldwin often spoke about how from the time a black child recognizes that he is not an equal member of the society in which he lives, the sense of inferiority and disenfranchisement does not steadily grow but accelerates in his mind as time passes.

In the novel, the full picture of John Grimes also coheres at an accelerating rate, until we are back with him on the threshing-floor, completely invested in him, our capacity for empathy expanded. The scene of John’s conversion, full of graphic and apocalyptic visions, is a signature achievement. Baldwin said Go Tell It on the Mountain is the book he had to write before he could write anything else. Reading the conversion scene evinces what a cathartic exercise that must have been for him. Danticat calls the novel, “. . . not just a well-thought-out and well-crafted lyrical work but also a protest chant, a hymn, a rebuke, a memorial, a prayer, a testimonial, a confessional, and, in my opinion, a masterpiece. . . [at the end] John is no longer the stranger who’d gone into the city and returned afraid. He is no longer a stranger to the reader. He is our brother. He is our son. He is our friend. He is us.”

Much of Go Tell It on the Mountain was written in the Café de Flore in Paris. Published in 1953, it established Baldwin as a literary force in mid-century America. By the late 1950s, he was back in the United States much of the time and active in the Civil Rights movement. In 1963, he gave a series of lectures on race, mostly in the South, and appeared at the August 28, 1963 March on Washington where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

In 1965, Baldwin debated prominent conservative William F. Buckley at the Cambridge Union in the United Kingdom on the question, “Did the American dream come at the expense of the American negro?” Baldwin won the debate overwhelmingly (the students voted in Baldwin’s favor 540–160) and it remains an epochal rhetorical moment in U.S. race relations. The debate was broadcast on the BBC and today should be mandatory viewing in every U.S. military officer commissioning program (Nicholas Buccola’s excellent 2019 book The Fire Is Upon Us probes the backgrounds of Baldwin and Buckley and the context of the times that brought them together that evening).

Writing to show the world as it is, Baldwin eschewed any temptation to suggest facile solutions to such a complex issue as race, identity, and the black experience. They do not exist. His characters, both major and minor, are as flawed and multidimensional as any characters in real life. This gives the novel a special depth and lasting power. The writer has coopted us in the experience.

Each generation of military leaders has a responsibility to honor the progress of the past while remaining sensitive to the fact that gains made are neither permanent nor, thus far, sufficient. The military is in the warfighting business where assignments and promotions should rest on merit alone. Aspiring to that ideal is right, but only while acknowledging that much of the “data” that feeds the meritocratic evaluation system actually derives from countless subjective decisions—human decisions. Meritocracies are not built and maintained on empirical data. Studying the problem of race through the many great American works of literature will help leaders better appreciate this fact.

When officers who have never worried about being the target of discrimination sound off quickly in dismissing a policy promoting diversity, while at the same time being poorly read on the black experience in America, I do not hear a well-considered and enlightened position. It shocks me today to hear young, white officers reflexively discussing race in the context of white victimization and grievance. This fixation with reverse racism is at best historically ignorant, at worst callously insensitive.

James Baldwin left the ministry and the church at age 17 and began work on Go Tell It on the Mountain. His personal and literary journey from that point forward was as difficult as it is remarkable. As much as any twentieth-century writer, he deserves much more than our respect. He deserves our enduring attention.

Bill Bray is a retired Navy captain and the Deputy Editor-in-Chief of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings magazine.

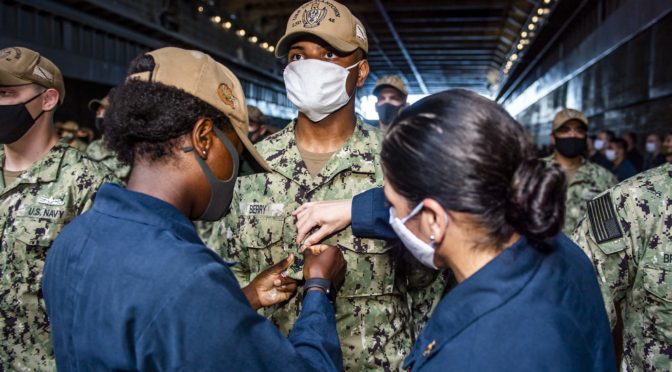

Featured Image: EAST CHINA SEA (July 31, 2020) Boatswain’s Mate Seaman Valentina Imokhai, from New York, left, and Chief Personnel Specialist Melissa Colon, from Fajardo, Puerto Rico, right, put a petty officer second class rank insignia on Yeoman 2nd Class Steven Berry, from Cleveland, as he is promoted during an advancement ceremony on board the amphibious dock landing ship USS Germantown (LSD 42). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Taylor DiMartino)