By Joshua Tallis and Ronald Filadelfo

Recapitalizing strategic sealift vessels would provide a needed catalyst for green maritime technology development, driving toward the Biden administration’s new shipping climate target while improving the US Navy’s warfighting edge. A greener merchant fleet, enabled by technology developed during the recapitalization of the aging sealift fleet (the vessels that bring US troops and materiel to foreign shores) would address an important source of climate change and increase the sustainment reach of the logistics fleet (the auxiliary vessels that keep warships on station). Such a maritime green revolution might even improve lethality.

Climate and the Shipping Forecast

Shipping is the most efficient way that humans distribute goods. Yet the industry’s scale still makes commercial vessels substantial global emitters. Ships often burn cheap, heavy fuels, the dregs of the refinement process, which means that as few as 15 of the merchant fleet’s largest vessels give off as much nitrogen and sulfur as the entire world’s stock of automobiles. Marine-related black carbon emissions, while not the world’s largest source of soot, are rising relative to other sources. This disproportionately impacts Arctic ice melt because the black specks settle lower in the atmosphere, landing on ice and absorbing more heat. In total, if shipping were a country, it would be the sixth largest emitter of CO2, behind Japan and ahead of Germany.

The merchant fleet has surely been moving to adopt more efficient vessels. A combination of optimized speed, more efficient engines, and larger hull sizes has contributed to substantial net improvements over time. Yet innovation has its obstacles. A recent move to low sulfur fuel in compliance with new International Maritime Organization (IMO) rules has allegedly increased emissions and may have contributed to a series of power failures at sea. Meanwhile, even in the face of environmental resistance by shipping lines to use Arctic routes, Russia continues to advertise the Northern Sea Route, raising the prospect of further environmental fallout from the shipping industry. It is in this context that the Biden administration has committed to join the IMO in reducing global shipping emissions to net zero by 2050.

A New Opportunity in an Old Problem

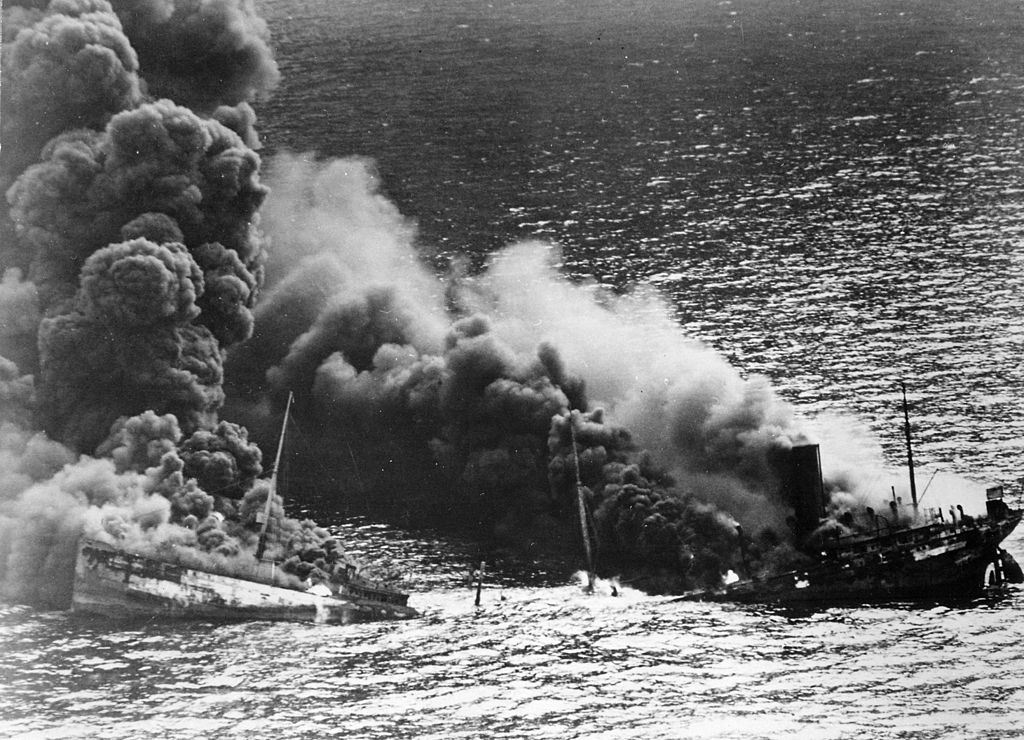

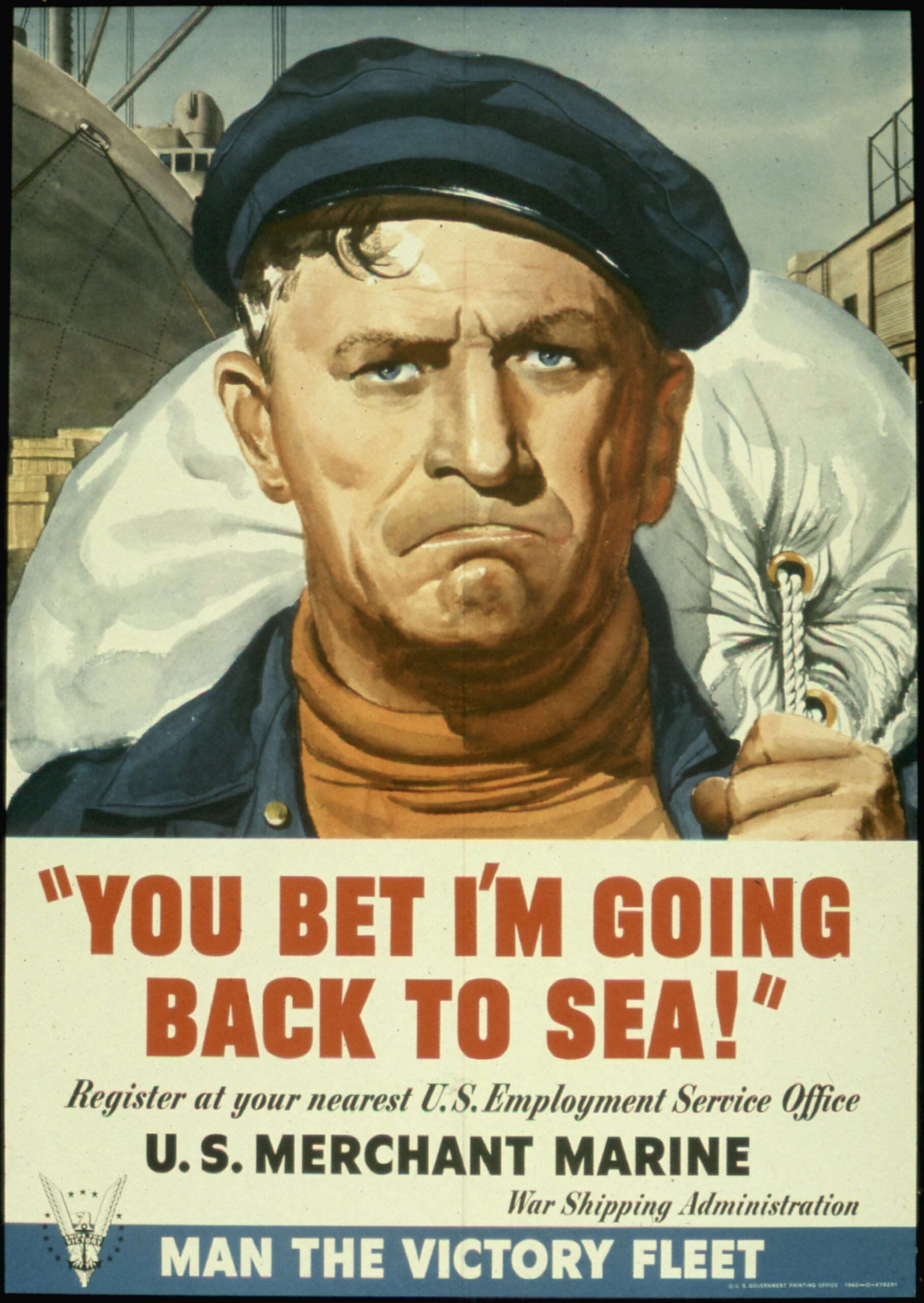

It is uncontroversial to note that the United States’ strategic sealift fleet—which includes ships operated by Military Sealift Command and those in the Maritime Administration’s National Defense Reserve Fleet and Ready Reserve Fleet—is aging and in need of recapitalization. During TRANSCOM’s 2019 “Turbo Activation” of the Ready Reserve Force, only 40% of vessels deemed “ready” (and only 60% of the fleet carried that designation to begin with) were able to get underway. The common culprit is age, with the average vessel maturity reaching around 45 years old. Therefore, the longstanding argument in favor of modernizing (ideally even expanding) the strategic sealift (and combat logistics) fleet is old in more ways than one.

What is new is the opportunity to push larger policy objectives through such a scientific and industrial effort as recapitalizing the fleet. Any such initiative should be used as an opportunity to push far greater federal funding into green maritime technologies, which would pay dividends for the sector at large. And where possible, it may even be the case that greener technologies could improve the US Navy’s warfighting edge.

There are any number of technologies that the nation’s sealift fleet could help iterate, including hybrid electric drives, stern flaps, and energy storage modules—each of which has been previously explored by the Navy for application among the combat and auxiliary logistics fleet.

Hybrid Electric Drive

Hybrid electric drives (HED) substitute a vessel’s gas turbine with stored electric power to propel the ship when operating at low speeds—somewhat akin to hybrid automobiles, which switch from gas to electric when conditions allow. Arleigh Burke-class destroyers (DDGs) are the Navy’s primary surface combatant with substantial remaining service life, so the Navy invested a significant amount of money to retrofit these ships with HEDs. The technology poses some risks, particularly given the short lag when shifting back to full power, which can be problematic for conditions that require high degrees of maneuvering responsiveness. As with many technologies that improve efficiency, the operational tradeoffs can be challenging to account for—one reason that the program resulted in most drives sitting on the pier.

Stern Flaps

A stern flap is a steel plate attached to the rear of a ship to extend from the hull bottom surface. This comparatively low-tech solution modifies the way water flows around the hull, reducing drag and hull resistance and yielding significant fuel savings. Stern flaps are one of the Navy’s main fuel-saving initiatives for DDGs. Pre-installation engineering studies estimated such additions would save about 4,000 barrels of oil per ship per year. Remarkably, in an era when estimates seem so often to miss the mark, real world implementation showed that those savings were indeed realized when assessed over the entire Arleigh Burke-class. Stern flaps are applicable to many classes of Navy and logistics ships, leaving room for further exploration.

Energy Storage Modules

Energy storage modules (ESM) are another fuel savings program previously considered by the Navy. To prevent total loss of electric power should a generator unexpectedly fail, Navy ships generally run more than one electric generator, even if the electric load is low enough to be serviced by only one. An ESM consists of a system of batteries that could provide sufficient power for the ship for the time it would take to bring a backup generator online, thereby allowing ships to operate with only one generator. As with HEDs, ESMs pose some operational risks, in this case particularly those of redundancy associated with single-generator operations. If the single operating generator fails, the ship could be left with little or no power. So to date, the technology is not used in the fleet.

Warfighting Edge

The policy and environmental mandates to move toward greener technology, including at sea, are straightforward and do not require modifications to existing operational policies (unlike other interesting proposals, such as changing minimal fuel requirements). And as seen, the Navy has been an innovator in pushing green technologies in the past. There is every reason to believe that a recapitalization of sealift forces could be a similar or greater catalyst today. Further research and development on technologies like the HED, to explore feasibility on other classes of Navy ships, including logistics vessels, is just one example of experiments ripe for a second look. Yet there is a final, added value from this experimentation for the Navy—a greener force is a more lethal force.

Already, tools that promote greener maritime operations could integrate well with missions that rely on slow, steady steaming—for example, station-keeping in a launch box, ballistic missile defense, or even some freedom of navigation operations. Strategic sealift vessels could similarly benefit from greater fuel economy, enabling this more vulnerable fleet to loiter or divert to secondary or tertiary ports of debarkation in the event a primary port is destroyed or inaccessible during conflict.

But the greatest single advantage to the warfighter from these capabilities is in extending, if not severing, the logistics cord with the combat logistics force. Logistics vessels with extended fuel economies would be able to stay on station for longer periods of time, capable of sustaining the combat fleet with greater responsiveness in the face of changing weather or operating locations.

Combat ships, outfitted with similar green adaptations, could expand their operating windows between replenishments at sea (RAS), which are the ultimate operational tether for non-nuclear surface forces. In theaters with expansive distances from at sea forces and onshore resupply locations (i.e., the Pacific), or where weather can force ships to divert or modify RAS schedules (i.e., the North Atlantic), substantive extensions of fuel economy could foster strategic innovations in fleet operations. And any cost savings from reduced fuel use are ideal funds to divert into training and maintenance pools, a small but valuable contribution that could contribute to extricating the Navy from its readiness debt. None of which is to comment on how a reduction in strategic reliance on fossil fuels might change how the Navy understands the strategic implications of certain maritime chokepoints in the event of open hostilities.

A green merchant fleet is an important contribution to combatting climate change. A green logistics fleet is a critical step toward more durable support to the Navy. A green combat fleet is a strategic asset in austere or hostile operating environments. And the first step to each of these objectives is taking the long-needed strategic sealift reinvestment as an opportunity to transform maritime research and development.

Dr. Joshua Tallis is a maritime and polar analyst at the Center for Naval Analyses. He is the author of The War for Muddy Waters: Pirates, Terrorists, Traffickers, and Maritime Insecurity.

Dr. Ronald Filadelfo is the research program director for energy, environment, and installations at the Center for Naval Analyses. The opinions in this article do not necessarily reflect those of CNA or the U.S. Navy.

Featured Image: U.S. sailors aboard the guided missile destroyer USS Fitzgerald pull in a fuel line on the ship’s forecastle during a refueling with Military Sealift Command fleet replenishment oiler USNS John Ericsson during Valiant Shield 2014 in the Pacific Ocean, Sept. 20, 2014. (U.S. Navy photo)