Read Part One here.

By Andrew Norris

Navy Doctrine on Planning for Maritime Security Operations is Inadequate

“Military planning is essential to everything that naval forces do.”1 If the Navy intends to successfully conduct maritime security operations (MSOs), it needs to be able to effectively plan for them. That planning is particularly essential at the operational level—namely, the level of command linking tactical missions with national strategic guidance.2 Navy planning is conducted in accordance with doctrine, specifically the Navy Planning Process (NPP). This section, after discussing foundational issues such as the nature of operations in the maritime security realm, summarizes the NPP and identifies inadequacies in the particular component of the process most impacted by planning for maritime security missions: mission analysis, as informed by staff estimates.

1. The need for operational-level thinking and planning for MSOs

A tactical action or mission is one aimed at accomplishing a single major or minor tactical objective.3 An example of a tactical maritime security mission is carrying a law enforcement official from a partner nation aboard a U.S. warship on a single occasion to provide that official a means of enforcing his nation’s fisheries laws. Such a mission is individually useful to the United States in promoting a stable rules-based order at sea and in establishing itself as the “partner of choice” for that nation in an era of great power competition at sea. It is episodically useful to that partner nation as well in deterring or interdicting violators of its fisheries laws, therefore helping to preserve an important natural resource and source of national income, which enhances its stability.

The effect of such a mission is dramatically enhanced if it is conducted as part of a major operation or campaign as opposed to a one-off, “whack-a-mole” activity. Performing this activity as part of a campaign or major operation leads to concerted activities that are “proactive and anticipatory rather than simply reactive, and are issue-centered rather than incident-centered.”4 Both Till and Vego teach us that “operational warfare at sea is the only means of orchestrating and tying together naval tactical actions within a larger design that directly contributes to the objectives decided by strategy.”5 Vego brings this maxim into the maritime security realm, opining that operational-level thinking and concepts “are absolutely necessary for the most effective use of one’s combat forces not only in a high-intensity conventional war but also in operations short of war.”6 The need for operational-level thinking and planning holds true for lower-threshold MSOs as well.

2. How the U.S. Navy conducts operational-level planning

“The characteristics of today’s complex global environment have created the conditions where the U.S. Navy must be prepared for a wide range of dynamic situations;” furthermore, “the nature of modern naval operations—which must span from open ocean to deep inland—interlinks continuously with other services, countries, and means of national power, and it often places the lowest tactical commander in critical strategic roles, necessitating that a thorough planning process be used.”7 For these reasons and more, the Navy has created a formalized planning process, the NPP, that is optimized for planning at the operational level.8 The NPP is designed to ensure that the employment of forces is linked to objectives, and integrates naval operations with the actions of the joint force. Accordingly, the terminology, products, and concepts in the NPP are consistent with joint planning, joint doctrine, and are compatible with other services’ doctrine.9

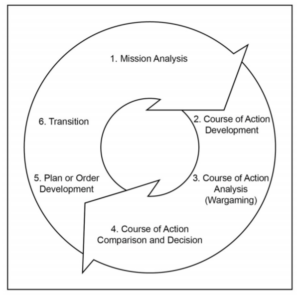

To accomplish its purpose, the NPP establishes sequential, iterative procedures to, in turn, progressively analyze higher headquarters tasking(s); to craft a mission statement; to develop and analyze courses of action (COAs) against projected adversary COAs (in some cases adversaries could be forces of nature or other emerging non-military threats); to compare friendly COAs against the commander’s criteria and each other; to recommend a COA for decision; to refine the concept of operation; to prepare a plan or operation order (OPORD); and to transition the plan or order to subordinates tasked with its execution. The NPP organizes these procedures into six steps, shown in Figure 2 below, which provide commanders and their staffs a means to organize planning activities, transmit plans to subordinates, and share a critical common understanding of the mission. The result of the NPP is a military decision that can be translated into a directive such as an operation plan (OPLAN) or OPORD.10

Military planning through utilization of the NPP is not a scientific or mechanistic process, but instead employs aspects of both science and art. The science involves such tangible aspects as disposition and number of ships, aircraft, weapons, supplies, and consumption rates, as well as the interplay of operational factors, such as time and space, that affect employment of the naval force. The art of military planning, on the other hand, is more conceptual. Operational art is defined as the cognitive approach by commanders and staffs—supported by their skill, knowledge, experience, creativity, and judgment—to develop strategies, campaigns, and operations to organize and employ military forces by integrating ends, ways, means, and risk.11 Through the application of operational art, the commander and staff identify the objectives and outline the broad concept of operations (CONOPS).

Dealing with the Unique Aspects of MSOs in the NPP

1. The unique aspects of MSOs

MSOs lie at the uncomfortable nexus between maritime law enforcement and naval warfare.12 According to Professor Till, operational art is not optimally employed to plan for the activities the world’s navies are actually having to conduct on a day-to-day basis, such as campaigns against piracy, narcotics or human smuggling and terrorism, patrols against human smuggling, or fishery protection.13 The reason for this, Professor Vego informs us, is that “[a]pplication of operational art in operations short of war is much more complicated than in high-intensity conventional war” due to a highly diverse and unpredictable operational environment, the dominant role of nonmilitary “force” factors in determining objectives, and human “space” predominating over geography.14 And, as we have seen, Professor Luke recognizes such a significant difference between MSOs and combat at sea that he felt the need to propose an entirely new theoretical paradigm, that of legitimacy, to reflect the unique “fundamentals and tenets that distinguish peacetime activities from warfare.”15 These unique fundamentals and tenets (which will be referred to as “factors” or “aspects”) include, as we have already seen, a “broad and growing array of legal regimes, treaties, and sources of authority that need to be fully appreciated, understood, and leveraged for success.”16

This understanding of the fundamental uniqueness of MSOs is not solely the province of theorists; it is recognized in doctrine as well. Specifically, Appendix A of the NPP—the only section of the NPP that directly addresses maritime security operations—refers to the “many facets” of maritime security, and states that “each maritime security activity is unique.”17 As the following discussion will show, this doctrinal assertion is not complemented by guidance to planners on how to account for and accommodate the unique aspects of MSOs that are so critical for operational success.

2. Where those unique aspects are best dealt with in the NPP

The unique aspects of MSOs are best dealt with in the mission analysis phase of the planning process, as informed by relevant staff estimates. Mission analysis, as the first step of the NPP, is “the foundation for the entire planning process.”18 When performed correctly, it provides the who, what, when, where, and why for the planning staff, and makes the development of the how possible. A non-exclusive list of topics an effective mission analysis should address includes:

- The tasks the command must complete for the mission to be accomplished;

- The purpose of the mission and tasks assigned;

- The limitations that have been placed on our own forces’ actions;

- The forces/assets available to support the operation;

- Additional assets required to support the operation;

- Gaps of knowledge that inhibit planning; and

- The various risks.19

Mission analysis leads to the delivery of a briefing to the commander and subsequent commander’s planning guidance. The briefing ensures the commander and staff have a common understanding of the overall situation, mission, intent, and planning guidance that facilitates COA development (the how).

The more unique, ill-defined, and unfamiliar the situation being analyzed, the greater the need to more closely examine the problem before or in conjunction with mission analysis.20 This close examination is accomplished by means of staff estimates. An estimate is a detailed evaluation of how factors in a staff section’s functional area or subordinate commander’s warfare area potentially impact the operation or mission.21 The estimate consists of significant facts, events, and conclusions based on analyzed data.22 Staff estimates provide a current status and an assessment of the ability of the command to meet the requirements of the assigned mission while identifying shortfalls and potential issues, as well as strengths and advantages. Every functional staff area has a responsibility to create and maintain a staff estimate.23 Types of estimates generated by maritime staffs include but are not limited to: (1) operations estimate; (2) personnel estimate; (3) intelligence estimate; (4) logistics estimate; (5) communications estimate; (6) civil-military operations estimate; (7) information operations estimate; and (8) special staff estimates (e.g., legal, public affairs, medical).24 The legal estimate is especially critical to MSOs.25

3. Existing doctrine related to conducting mission analysis and crafting staff estimates in MSOs is inadequate

Although existing planning doctrine correctly identifies operations short of war as challenging, different, and unique, it does not provide much in the way of guidance to planners on how to deal with these qualities. NPP Appendix A.2.3., while stating that the NPP is “well suited to support all aspects of sea control and power projection,” acknowledges that some “minor accommodations” may have to be made to the NPP when planning MSOs due to the fact that “[m]ost maritime security operations will entail a requirement for cooperation with or subordination to a multinational partner or civil law enforcement body to ensure the process is compatible with the expectations of the partners.” Though Appendix A.2.3. provides some guidance on mechanisms for effecting such cooperation—reciprocal exchange of liaison officers to participate in planning for multinational operations, for example—it is entirely silent on the issues raised by such cooperation, and regarding exactly what “minor accommodations” need to be made to the mission analysis to account for such cooperation. As for the legal estimate, which Appendix A.2.3. identifies as being “especially critical to a maritime security operation” which will “drive the concept development as well as rules of engagement or rules for use of force,” there is no further guidance on what, specifically, should be considered to take into account the unique aspects of MSOs.26

The Stability Operations Manual provides a bit more guidance, though nothing that can be considered holistic or detailed.27 Since MSOs are a subset of stability operations overall, and since both MSOs and stability operations are maritime operations short of war, the manual’s guidance may be of some utility in conducting the mission analysis for MSOs. The manual specifies that issues such as whether involved nations are UNCLOS signatories, the existence of maritime territorial disputes, the identification of “appropriate public and private international maritime laws,” and important cultural and other considerations should all be considered during the mission analysis phase of stability operations.28 Though somewhat of an improvement from the very sparse guidance in the NPP, this list still only exists in anecdotal, not systematic form, and is unclear about why the listed items are important, and what about them should be the subject of mission analysis.

The Constraint-Restraint-Enabler-Imperative (C-R-E-I) Model Introduced and Explained

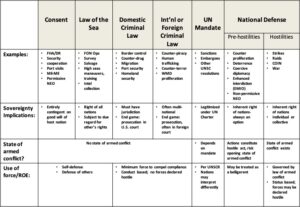

According to Professor Till, “[d]efective doctrine is quite clearly the high road to defeat [while] effective doctrine is a very significant force multiplier.”29 As this article established earlier, the U.S. Navy will be expected to successfully engage in day-to-day MSOs along the full spectrum of violence including, increasingly, lower-threshold constabulary operations. Such operations are complicated and unique, and need to be effectively planned at the operational level through employment of the NPP and its embedded operational art principles. However, guidance is sparse on exactly how planning for such unique operations is supposed to occur. The C-R-E-I model for crafting appropriate staff estimates as part of the mission analysis is meant to fill this lacuna. While it is impossible to set out a cookie-cutter list of every item that should be considered in the staff estimate for the planning of a maritime security operation, consideration of applicable constraints, restraints, enablers, and imperatives applicable to a particular MSO spans the universe of authority-based considerations that ultimately determine the legitimacy of such operations. The model is discussed below:

Constraints are obligations that prohibit an operation from occurring at all, or prohibit certain activities or outcomes during the course of an operation. Constraints may derive from international obligations a state has chosen to accept, or from domestic sources such as a constitution or legislative enactments. In the United States, a constitutionally-derived constraint is the Fifth Amendment’s admonition that “[n]o person . . . shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law,” which serves as a direct prohibition against gathering evidence against a person through compulsive means such as torture. An example of a legislatively-derived constraint is the Posse Comitatus Act, which (along with derivative instructions and directives) prohibits the armed forces in the Department of Defense from directly engaging in law enforcement operations. As for constraints that derive from the international obligations to which a state chooses to subject itself, examples of relevance in the maritime security realm include the principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits a nation from returning an individual to a nation where that individual would face a threat of loss of life or freedom, or of torture; the prohibition in UNCLOS Article 73(3) of criminal prosecution of individuals violating a fisheries law in a state’s EEZ; or the customary international law principle, embodied in UNCLOS Article 92(1), that flag states enjoy exclusive jurisdiction over their ships on the high seas—a principle that conversely constrains all other nations, absent unusual circumstances, from asserting any jurisdiction as a matter of right over a foreign vessel in that maritime zone.

Restraints are factors or conditions that limit the scope or range of permissible activities during a maritime security operation. They derive from the same sources as constraints. An example in the U.S. of a domestically-derived restraint is the reservation of authority within the Coast Guard chain of command, which manifests itself in the requirement that subordinate units must obtain a “statement of no objection” from higher authority before acting in certain circumstances. A restraint that derives both from domestic and international sources is the limitation on the use of force for constabulary purposes to the minimum force reasonable and necessary under the circumstances to accomplish a law enforcement mission. Restraints that derive from the international law of the sea include the limitation embodied in UNCLOS Article 27 on criminal prosecution of vessels and crew engaged in innocent passage, and restrictions on the right of hot pursuit such as the requirement that it be continuous and uninterrupted, and the extinguishment of that right once the pursued vessel enters a foreign territorial sea.

Enablers: Perhaps the most important (in terms of mission success) of the four-part analytical framework for preparing the staff estimate for MSOs are enablers. Enablers promote the successful conduct of a maritime security operation, notwithstanding the challenges imposed by constraints, restraints, and imperatives. Like constraints and restraints (and, as we shall see, imperatives), enablers can derive from international or domestic sources. Examples of enablers at the international level include flag state consent to foreign law enforcement activities aboard a flagged vessel on the high seas, which may be provided on an ad hoc, case-by-case basis, or through standing consent memorialized in an international agreement; the declaration by a state of an EEZ, which is a necessary precursor for it to exercise its sovereign rights as set out in UNCLOS Article 56 and to enforce those rights as provided in UNCLOS Article 73; regional agreements that promote cooperative security measures such as the sharing of monitoring, control, and surveillance data or the establishment of regional intelligence fusion centers to combat transnational organized crime; bilateral agreements that enable direct law enforcement support such as the carriage of shipriders from one nation aboard an enforcement vessel of another nation; and extradition treaties to allow interdicted suspects to be repatriated to another nation for prosecution. An example of an enabler with both international and domestic components is adoption by both a flag state and a port state of generally accepted international regulations, procedures and practices such as those established by the SOLAS Convention, which enables authorities of the port state to conduct an examination of a foreign vessel in its internal waters to ensure its compliance with these standards. Domestic enablers include the enactment of legislation and regulations that authorize desired maritime activities; the establishment of domestic architecture that permits a law enforcement matter to be taken all the way from detection through prosecution (i.e. to achieve a “legal finish”); and the establishment and utilization of mechanisms to coordinate the activities of various government agencies or ministries to achieve a common, agreed-upon outcome.

Imperatives are obligations that mandate certain activities in the maritime realm. Examples of imperatives with both an international and a domestic component in the maritime realm include the obligation embodied in UNCLOS Article 98 to go to the assistance of persons lost or distressed at sea; the affirmative obligations of the flag state to “effectively exercise its jurisdiction and control in administrative, technical and social matters” over ships flying its flag, as detailed in UNCLOS Article 94; the affirmative obligation in UNCLOS Article 61(2) on states to “ensure through proper conservation and management measures that the maintenance of the living resources in the exclusive economic zone is not endangered by over-exploitation;” the flag state’s obligation to ensure compliance by flagged vessels with conservation and management measures (CMMs) enacted by regional fisheries management organizations; the affirmative duty to cooperate in the suppression of illicit traffic by sea on signatories to the 1988 Vienna Drug Convention; and carrying out any affirmative obligations in UN Security Council resolutions.

Explanations and Caveats

Users of the C-R-E-I Model must avoid unnecessary quibbles about the appropriate characterization of a particular factor of importance to an MSO. For example, reasonable minds may differ as to whether the rule that, “[t]he right of hot pursuit may be exercised only by warships or military aircraft, or other ships or aircraft clearly marked and identifiable as being on government service and authorized to that effect”30 is a constraint or a restraint. The correct answer is that it does not matter. As long as utilization of the C-R-E-I model forces planners to identify, in a structured manner, the rule set regarding the type of vessels that may be used to engage in hot pursuit (assuming in this hypothetical that this is of significance to the intended MSO), then it has improved mission analysis and therefore the prospect for success of the intended MSO.

While the identification and analysis of applicable constraints, restraints, enablers, and imperatives relating to an intended MSO is a vitally important function, it is only the first step. Such identification and analysis can also be used to shape an MSO by converting undesired constraints, restraints, and imperatives into enablers. For example, a constraint such as prohibition against boarding a foreign vessel on the high seas can turn into an enabler through advance consent by a flag state to the conduct of desired high seas activities in advance of an MSO. The point is that authority-based factors are not static or immutable, and in fact can and should be actively shaped into enablers to promote operational success.

Another point about the model is that it is authority-, not capability-based. Such matters as vessel and crew endurance, vessel speed and other capabilities, transit times, etc., are not unique to MSOs and are not directly addressed by this model. However, proper utilization of the model significantly impacts capabilities-based planning considerations. For example, limitations (constraints or restraints) inherent in the use of force regime applicable to an intended MSO that are exposed during mission analysis should drive commanders to ensure, not only that the crews of vessels that will participate in the MSO are properly and adequately trained, but also that the vessels and crews are properly equipped with the means to lawfully employ force if required. As another example, if mission analysis reveals that a partner nation has a domestic legal requirement (an imperative) that suspects must be brought before a magistrate within 24 hours of interdiction, the operational commander must ensure that assets employed in an intended MSO have the capacity to comply with that requirement, or else the “legal finish” to the operation may be jeopardized.

Finally, as a follow-up to proper training, while this model is conceived for operational-level commanders and planners, mission commanders must also be facile in their ability to identify, understand, and react to relevant constraints, restraints, enablers, and imperatives. This indicates the need for robust professional military education and continued pipeline training for mission commanders and their support personnel. That training and facility should include clear lines of communication from tactical commanders to operational commanders and their staffs. As Advantage at Sea reminds us, “[a]ctivities short of war can achieve strategic-level effects.”31 The consequences of tactical commanders failing to understand constraints, restraints, or imperatives they encounter, or failing to properly exploit enablers, are too dire not to demand facility with the C-R-E-I model at the tactical level as well.

Conclusion

The C-R-E-I model builds upon and endorses Professor Luke’s legitimacy theory for thinking about maritime operations short of war as being the only theoretical model that recognizes the essence of their uniqueness and singularity. It follows his linkage of legitimacy to authority (see Figure 3), but provides granularity to authority-based considerations by parsing them into constraints, restraints, enablers, and imperatives. It also “operationalizes” his theory by providing a concrete model for planners to employ during the stage of the planning process most suited to consideration of the unique features of MSOs: the mission analysis phase of the NPP. Without such a disciplined and systematic approach by planners more accustomed to planning for combat operations at sea, there is the ever-present “danger of warfighters falling back into doctrine designed for combat—‘heavy metal thinking’—in such things as peace operations where such thinking is not appropriate.”32

This failure of planning has numerous potential negative operational consequences, including, but not limited to, legal challenges against aspects of the underlying operation that could impact the “legal finish.” Though admittedly not in the lower-threshold constabulary realm, federal lawsuits brought by aggrieved parties in United Nations Security Council (UNSC)-authorized interdiction actions are indicative of the nature of potential legal challenges across the spectrum of operations short of war. These include Tarros v. United States, in which the plaintiff sought damages related to the “blockage and diversion” of his vessel that occurred pursuant to UNSC. Resolutions 1970 (2011) and 1973 (2011), and Wu Tien Li-Shou v. United States, in which the plaintiff sought damages due to the wrongful death of his fishing vessel’s master and the negligent destruction of his vessel resulting from the rescue of a fishing vessel by U.S.-NATO forces enforcing UNSC Resolutions.33 Though these suits were unsuccessful, other challenges in European and international courts arising from lower-threshold constabulary operations have been successful, and serve as a harbinger of legal consequences that could result in improperly planned MSOs conducted with or on behalf of allies and partners.34

Beyond legal challenges, other potential consequences of improper planning for MSOs include career ramifications throughout the chain of command and ill will or even a diplomatic incident with an ally or partner. All of these potential consequences run counter to Advantage at Sea’s admonition to the Naval Service to “partner, persist, and prevail across the competition continuum,” and could lead to failure to achieve the strategic objective of prevailing in day-to-day competition. Adoption and application of the C-R-E-I model should ensure that thinking and analysis are properly focused on the “fundamentals and tenets that distinguish peacetime activities from warfare,” which will greatly enhance the prospects of success of the MSO being contemplated and, ultimately, of the strategy enunciated in Advantage at Sea.

Capt. (ret.) Andrew Norris works as a maritime legal and regulatory consultant, and has been retained to create and teach a new five-month maritime security and governance course for international officers at the U.S. Naval War College. He retired from the U.S. Coast Guard in 2016 after 22 years of service. Prior to attending law school and joining the Coast Guard, Capt. (ret.) Norris served in the U.S. Navy as a division officer aboard the USS KIDD (DDG-993) from 1985-1989. He can be reached at +1 (401) 871-7482 or anorris@tradewindmaritimeservices.com.References

[1] Navy Warfare Publication (NWP) 5-01, Navy Planning (Ed. December 2013), 1-1.

[2] Geoffrey Till, Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-First Century: Fourth Edition (New York: Routledge, 2018), 159-160.

[3] Milan Vego, “Operations Short of War and Operational Art,” Joint Forces Quarterly 98 (3rd Quarter 2020): 38-49, 43.

[4] Till, Seapower, 458.

[5] Till, Seapower, 162.

[6] Vego, “Operations Short of War,” 38.

[7] NWP 5-01, 1-2.

[8] “Optimized” does not mean “exclusively” – “Through the NPP, a commander can plan for, prepare, and execute operations from the operational through the tactical levels of war.” NWP 5-01, 1-4.

[9] NWP 5-01, 1-5 – 1-6.

[10] NWP 5-01, 1-4.

[11] NWP 5-01, 1-2.

[12] Kraska and Pedrozo, International Maritime Security Law, 2.

[13] Till, Seapower, 165.

[14] Vego, “Operations Short of War,” 44. Professor Vego also correctly advises that the process of determining the Desired End State in operations short of war is “far more complex and elusive” than in a high-intensity conventional war. Ibid.

[15] Ivan Luke, “Naval Operations in Peacetime: Not Just “Warfare Lite,” Naval War College Review 66, no. 2 (Spring 2013): 10-26, 15.

[16] Luke, “Naval Operations in Peacetime,” 11.

[17] NWP 5-01, Appendix A.2.3.

[18] NWP 5-01, 2-1.

[19] NWP 5-01, 2-2.

[20] Ibid.

[21] NWP 5-01, Appendix K-1.

[22] NWP 5-01, App. K.3.1

[23] NWP 5-01, 2.3.3.

[24] NWP 5-01, Appendix K.2.1.

[25] NWP 5-01, Appendix A.2.3.

[26] In fairness, Appendix N of NWP 5-01 does provide some further guidance for the legal estimate generally, but this guidance is generic to all operations and is not focused on the unique aspects of MSOs.

[27] MCIP 3-33.02/NWP 3-07/COMDTINST M3120.11, Stability Operations Manual (25 May 2012).

[28] Stability Operations Manual, 3-7 – 3-8.

[29] Till, Seapower, 123.

[30] The Convention on the Law of the Sea, Dec. 10, 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 397 (UNCLOS), Article 111( 5.).

[31] Tri-Service Maritime Strategy “Advantage at Sea,” 17 December 2020, 6.

[32] Till, Seapower, 165.

[33] Tarros v. United States, 982 F. Supp. 2d 325, 327 (S.D.N.Y. 2013); Wu Tien Li-Shou v. United States, 997 F. Supp. 2d 307, 308–09 (D. Md. 2014), aff’d, 777 F.3d 175, 179 (4th Cir. 2015). These and more are discussed in Brian Wilson, “The Turtle Bay Pivot: : How the United Nations Security Council Is Reshaping Naval Pursuit of Nuclear Proliferators, Rogue States, and Pirates,” Emory International Law Review 33, issue 1 (2018): 1-90.

[34] See Brian Wilson, “Human Rights and Maritime Law Enforcement,” Stanford Journal of International Law 52, no. 2 (July 2016): 243-319.

Featured Image: Maritime Operational Planners Course at the U.S. Naval War College (Credit: www.usnwc.edu)